Menschen und Leidenschaften

| Menschen und Leidenschaften | |

|---|---|

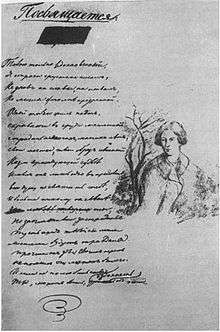

First page autograph | |

| Written by | Mikhail Lermontov |

| Characters |

Yuri Volin Nikolai Volin Lyubov, his daughter Marfa Gromova, Yuri's grandma |

| Date premiered | January 28, 1948 |

| Place premiered | Abakan, Khakassia, USSR |

| Original language | Russian |

| Subject |

Family conflict unhappy love |

| Genre | Romantic drama |

| Setting |

Provincial Russia Gromova's estate |

Menschen und Leidenschaften (Russian: Люди и страсти; English: Men and Passions) is an early drama by Mikhail Lermontov, written in 1830 and first published in Saint Petersburg in 1880 by Pyotr Yefremov in the compilation Early Dramas by Lermontov.[1][2]

Plot summary

Young Yuri Volin has to make a difficult choice between staying with his rich, overprotective grandmother and departing to Germany with his financially struggling father. Yuri is passionately in love with one of his two cousins, Lyubov, who loves him too.

Enter the scene the scheming housemaid Darya with her own vile recipe for making the boy stay at home, and the latter's uncle who finds out about Yuri's romantic leanings towards his daughter and is outraged with the idea of two cousins being in love. As a result of Darya's intrigue, the boy gets cursed by his misguided father (who believes the rumours of his son's two-facedness). Becoming a witness to Lyubov's clandestine conversation with Zarutsky and (mistakenly) construing it as a sign of infidelity on her part, the young man first challenges his hussar friend to a duel, then commits suicide.[3]

Background

Lermontov spent his childhood years with his grandmother Yelizaveta Arsenyeva and only on several occasions was allowed to see his father Yuri. His autobiographical second drama (which followed The Spanyards, 1830) concerns this bitter family feud which by the late 1820s has come to a head. Still, while the plotline is based on real facts (archive documents corroborate this), similarities between characters and their prototypes are not necessarily obvious (grandmother Gromova is pictured here as an egotistic 80-year-old religious hypocrite, which Arsenyeva wasn't).[1]

The poem features a dedication (a 20-line verse, starting with: "Inspired by you only / I was writing these sad lines...") but the addressee of it remained unknown. Her hand-written name on the first page autograph was blackened out, with only a drawing of a girl's face and a bare little tree remaining. Two possible candidates have been suggested, a distant cousin Anna Stolypina and Yekaterina Sushkova, but no conclusive evidence has been put forward to back either claim.

According to critic N.A.Lyubovich, stylistically Menschen und Leidenschaften combines two basic elements, those of the 18th-century realistic French comedy and the German drama of the Sturm und Drang period, with Yuri Volin's passionate rhetoric reminding similarly volatile monologues in early Friedrich Schiller's work. Some critics noted similarities also with the early Vissarion Belinsky drama Dmitry Kalinin (1830-1831), both protagonists professing ideas which were heatedly discussed in Russian student circles of the time, including those concerned the Saint-Simon book Nouveau Christianisme (1825).[1]

According to critic N.M. Vladimirskaya, Yuri Volin is not so much a self-portrait, as the young author's attempt to draw a psychological portrait of his generation, as he saw it, stricken by turmoil and depression which set after the 1825 Decembrist revolt. In many ways Yuri Volin reminds the protagonist of Lermontov's poems of the time, like "Solitude", "The Storm", "1830. July the 15th", a young man who is lonely, detached and disillusioned. For the first time, though, the "Byronic hero" has been taken out of his picturesque "romantic" environment to be placed in a domestic setting.[2]

Arsenyeva's will in its final part corresponds to the document quoted in the play.[4] The same is true for Yuri Lermontov's 1831 will, which read: "You must be aware of the reasons for us two having been driven apart and I am sure you won't blame me for that. I only wanted to make sure that your fortune wouldn't be taken away from you, even if I myself suffered the most considerable loss." It's been suggested that the prototype for Zarutsky was Lermontov's friend and relative Alexey "Mongo" Stolypin. Housemaid Darya Grigoryevna Sokolova (née Kurtina) and servant Andrey Ivanovich Sokolov (here - Ivan) were real people too, although the extent to which the former had been responsible for the boy's troubles in reality remained unclear.[2][5]

Lermontov's memories of his two years in the Moscow University's boarding school informed fragments of this drama, too; some remarks hint at the air of "free-thinking" that he'd enjoyed there and also at a certain conflict with the authorities which might have provided the reason for his leaving the school (mainstream biographical sources maintain that the reason was trivial; the elitist boarding-school was to be transformed into an ordinary gymnasium and the parents withdrew their children from what they saw as a downgraded school).[2]

References

- 1 2 3 Commentaries to Menschen und Leidenschaften. The Works of M.Yu.Lermontov in 4 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow, 1958. Vol. 3. Pp. 489-491.

- 1 2 3 4 Vladimirskaya, N.M. (1980). "Menschen und Leidenschaften". The Lermontov Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-01-13.

- ↑ Menschen und Leidenschaften, full text in Russian

- ↑ Literary Heritage, Vol. 45-46, Moscow, 1948. P. 635

- ↑ Shchyogolev, P.E., The Book on Lermontov. Priboy, Leningrad, 1929, Vol.1