Mendocino War

The Mendocino War was a violent conflict from July 1859 to January 18, 1860, between white settlers and local natives (mainly Yuki tribes) in Mendocino County, California. It was caused by settler intrusion on native lands and subsequent native retaliation, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of natives. In 1859, a band of locally sponsored rangers led by Walter S. Jarboe, called the Eel River Rangers, raided the countryside in an effort to remove natives from settler territory and move them onto the Nome Cult Farm, an area near the Mendocino Indian Reservation. By the time the Eel River Rangers were disbanded in 1860, Jarboe and his men had killed 283 warriors, captured 292, killed countless women and children, and only suffered 5 casualties themselves in just 23 engagements. The bill to the state for the rangers’ services amounted to $11,143.43. Scholars, however, claim that the damage to the area and natives in particular was even higher than reported, especially given the vast number of raiding parties formed outside of the Eel River Rangers. Frustrated with the inadequacy of federal protection, settlers formed their own raiding parties against the natives, joining Jarboe in his mission to rid Round Valley of its native population. Those that survived were moved to the Nome Cult Farm, where they experienced hardships typical of the reservation system of the day. After the conflict, contemporaries claimed that the conflict was more of a slaughter than a war, and later historians have labeled it a genocide.

Background

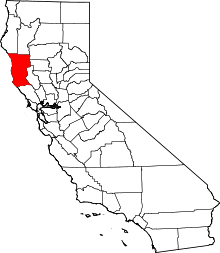

Round Valley, located in northeastern Mendocino County in Northern California, was home to various Native American tribes. The most populous of these local tribes were the Yuki, whose territory was roughly 1,100 square miles.[1] The Yuki were not one political people; rather, they were several autonomous groups that shared both language and culture, with each community having its own leadership.[2] In 1853, California started its Indian Reservation System, which was headed by Thomas J. Henley (Superintendent of Indian Affairs), and by 1854 Round Valley was discovered by white settlers.[3] Frank Asbill, the first white man to see the territory, estimated that there were about 20,000 natives in the area at the time. Scholars now believe this number is a little high, but by 1856, there were 12,000 Native Americans in Round Valley.[4] Although a few families moved into native territory, many of the settlers were hunters, fugitives, drifters, and the like. In general, they were people who lived off of the land, who traveled to the area for its resources.[3] In the same year, Thomas Henley sent Simmon Pena Storms to start the Nome Cult Farm.[3] Originally meant to be a resting point for natives and people traveling to the Mendocino Reservation, the Nome Cult Farm grew to become a reservation of its own, occupying 5,000 acres of northern Round Valley. This division of the 20,000 acre territory left over 15,000 acres for white settlement.[3]

Seeds of conflict

Despite the amount of land set aside for white settlement, the government had trouble stopping newcomers from settling all over the valley, including on the Nome Cult Farm and Mendocino Reservation.[5] As settlers moved into what was designated native territory, it became hard for the natives to survive. Those that lived on the Nome Cult Farm lived a life of hardship. In a type of indentured servitude, the natives raised their crops but reaped little of the actual benefits.[6] Natives were not protected but were subject to brutal treatment that included assaults, rape, murder, theft of their property, disease, and starvation.[7] Many white settlers who encroached on native territory engaged in kidnapping, stealing Native women and children and subjugating them to servitude or sexual abuse.[8] Natives at the Nome Cult Farm were overworked, and could even be killed if their work was not up to the standards of the reservation.[9] White settlers continued to exploit native land, with many families fencing in thousands of acres each.[10] They removed fences from the Nome Cult Farm and allowed their herds to graze on and through native land, some of which was already filled with crops.[11] The California Reservation System, which was subject to corruption, fraud and misuse of federal funds, provided little recourse.[12] As more settlers encroached on native land and resources, native food sources dried up on and around the reservations.

Escalation

Since ranching methods at the time were not very advanced (barbed wire had not been invented), the settlers had trouble keeping their livestock on their land. Many tried to train their animals to stay in a certain area, but this was not always effective. Livestock often wandered, and the local terrain made matters worse. The territory was new, unfamiliar, and full of hazardous cliffs and predators, and many cattle and horses wandered off and died of natural causes.[13] However, the settlers blamed the natives for any animal that went missing, believing that they were the targets of “Indian Depredations”, holding public meetings to stir up animosity towards the natives.[11] In retaliation, they continued their assaults on native land and resources. With no police force at hand, the reservation was powerless to stop local theft of native property or abductions of native people.[7] Locals like Dryden Lacock even stated that settlers, including himself, were engaging in small raiding parties that killed “50-60 Indians a trip”.[6] Finally, on the brink of starvation and left with almost no options, the natives began to retaliate. In 1857 a Yuki shot a man named William Mantle while trying to cross the Eel River, and in 1858 a white man named John McDaniel was murdered.[6] Both had been famous for crimes committed against Native Americans, and reports from the U.S. Army claim that the natives were provoked in both instances.[14]

State and federal involvement

As tensions rose and natives began retaliating for crimes committed against them, the settlers petitioned the U.S. Army for aid. In 1859 the 6th U.S. infantry led by Major Edward Johnson was called to Round Valley.[6] Major Johnson sent Lieutenant Edward Dillon ahead with 17 men to scout the area and assess the situation. Lieutenant Dillon reported back that the settlers misrepresented the situation. Instead of settlers falling prey to natives, the settlers had in fact already killed hundreds of natives, whose hostile actions had been taken out of revenge or in an effort to survive. The problem, he reported, went all the way up the chain to Supt. Henley, who had been involved in organizing many of these raiding parties.[15] In fact, Supt. Henley was in league with Judge Serranus C. Hastings (a former Iowa Supreme Court Justice), who helped him design plans for the removal of natives from the local territory. As part of their plan, they launched raiding parties and held town-hall style public gatherings where settlers aired their grievances, leading to increased racial prejudice and hatred towards the natives.[16] Judge Hastings was also involved in real estate and livestock trade, and in one instance, the natives stole Judge Hastings’s $2,000 stallion in retaliation for the beatings they received at the hands of Judge Hastings’s ranch manager, H.L. Hall.[17] Hall had been involved in many brutal assaults on natives. He complained to Lieutenant Dillon that the natives were stealing white supplies. Dillon urged Hall to let him handle the situation, but Hall ignored the command and took his own men raiding. By March 23, 1859, Hall and his men had killed about 240 natives.[15] Dillon reported that Hall did not distinguish between guilty natives or innocent ones, and that his murders of even women and children were unprovoked.[18] In fact, later on when Hall asked for soldiers at his property to protect his livestock, the soldiers refused to do anything to help him, since they were only ordered to defend a native onslaught, and they did not believe what was happening resembled a native attack.[19] The natives faced a choice of either starving to death on the reservations that provided them with no food, or venturing off into the mountainous regions of Mendocino County and risk slaughter by local settlers.

Walter S. Jarboe and the Mendocino War

As the conflict reached a boiling point, Judge Hastings made the executive decision to fire Hall and move all of the remaining natives to the Mendocino Reservation, more to save his property than for the protection of the natives.[20] In June 1859 the “Citizens of Nome Cult Valley”, a group of 39 settlers from Round Valley, petitioned the governor of California, Governor John B. Weller, for help in protecting the settlers from native attacks.[21] This petition, promoted and pushed for by Henley and Judge Hastings, was one of more than a dozen letters and petitions that the white settlers of Round Valley sent to the governor requesting government funding for volunteers who sought to protect white property.[22] Within these petitions, the settlers stated their intentions to remove the natives from Mendocino through a “war of extermination”.[23] Weller turned to the Army for advice on the petition, seeking to know whether or not the allegations of the settlers were true, since the petitions alleged that over $40,000 in property damages had occurred and over 70 whites had been slain by natives. The petitions also requested that Walter S. Jarboe, a Mendocino County resident, be assigned captain of this group.[24] In 1858, Jarboe had been a leader on a raid in the Mendocino Reservation that killed over 60 natives.[15] Countering the petitioners' claims, Major Johnson and Lieutenant Dillon issued reports telling a different story, claiming that only 2 whites and about 600 native had been killed in the past year.[15]

In the meantime, Hastings had grown tired of waiting, and created a new company anyway, without federal funding, with Jarboe as captain. The company was often referred to as the Eel River Rangers, and Hastings and Henley promised to provide the funding (they later went back on this promise, forcing the state to pay for Jarboe and his men).[25] From July 1859 to January 1860, Jarboe and his men ravaged native lands and massacred many natives. Claiming that the natives were guilty of theft and violence, Jarboe and his men engaged in an “ethnic cleansing genocide”.[26] Trying to justify his actions, Jarboe and his men used carcasses from plundered villages to try to give evidence for native thievery. It was a shoot-first, ask-questions-later approach that gave Jarboe and his men the powers of “judge, jury, and executioner”.[27] From July through the middle of August, Jarboe and his men had already killed 50 men, women, and children, prompting Major Johnson to write to Governor Weller. The governor wrote to Jarboe several times, sanctioning the raids, but asking Jarboe to leave out women and children and any innocent natives. Jarboe largely ignored these letters.[28] Through October Jarboe and his men continued to rampage through the countryside, killing and capturing natives. Those natives they captured were sent to the Mendocino Reservation and the Nome Cult Farm.[29]

The natives were left facing major challenges. Working against them were hunger, unequal weapons, repeated and surprise attacks, their vulnerable position on reservations, and their lack of ability to speak on their own behalf. Jarboe's forces also alienated some white settlers, slaughtering their livestock if they refused to give them food or the necessary supplies.[25] However, most of the damage was done to the natives and was especially deadly given the timing. With winter around the corner, the natives had spent months preparing and harvesting crops. Now, with raids, the men who farmed and hunted and the women who gathered and made the food were killed, and native stores of winter supplies were plundered and lost.[30] Jarboe and his men meanwhile continued their raiding and killing through the winter with the goal of removing the natives completely from Round Valley.[31] Some settlers also decided to assist in this cause, with ranchers leading attacks and raiding parties of their own. In one 22-day period, 40 ranchers killed at least 150 natives.[29] Finally, on January 3, 1860, Governor Weller disbanded Jarboe's group.[32] The public swiftly opposed this decision, petitioning Governor Weller to reinstate the Eel River Rangers, but the protest was unsuccessful.[33]

Aftermath and public reception

On February 18, 1860, Jarboe summarized his record, claiming that in 23 engagements, he and his men killed 283 warriors, captured 292 prisoners, while only sustaining 5 casualties themselves. The bill to the state for their five months of service was $11,143.43.[34] However, scholars now believe that the number of native casualties was grossly understated, as was the cost to the state. New California Governor John G. Downey now inherited the massive debts incurred by Jarboe and the settlers’ raids, debts that the state could not afford to pay.[31] Damage done to Yuki and other tribal cultures was incalculable.

The public reception of the conflict was mixed. A newly created Joint Special Committee on the Mendocino Indian War (also called the Select Committee on Indian Affairs) heard testimony from local settlers. The evidence was contradictory, with stories differing from each account, but some things remained consistent. Jarboe claimed that his actions were provoked by citing numbers of whites killed, but Dillon’s reports contradicted those statements. Dillon wrote to his superiors that white settlers were at fault for the entire conflict, and that the locals had funded the slaughter.[35] Many settlers claimed that the natives began the trouble by stealing cattle, while others testified that natives were allowed to eat the cattle and horses that strayed and died of natural causes.[34] Nevertheless, a general consensus emerged that the settlers wanted the natives off of their land and used any means necessary to force them out, including blaming natives for stealing livestock. The investigation concluded that no war had actually occurred in Mendocino County, since the slaughter of natives who offered little resistance and launched no counterattacks could not be considered a war. Rather, the conflict could be more correctly labeled as massacre, and later on historians began calling it a genocide. The committee also recommended some laws to help protect California Indians in the future, but none of them were ever put into place.[34]

Between the time people settled in Mendocino County and the end of the ‘war’ (1856-1860), the population of Indians decreased by 80%.[36] The rest were relegated to the Mendocino Reservation and the Nome Cult Farm.[36] In the late 1880s, tensions left unresolved from this conflict would lead to the Round Valley War when, in defiance of federal authority, settlers once again began to take over areas of the reservation, ignoring federal policies and settling on Yuki lands.[37]

Notes

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 16.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 180.

- 1 2 3 4 Secrest (1988), p. 16.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 36.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 4 Secrest (1988), p. 17.

- 1 2 Baumgardner, p. 61.

- ↑ Lindsay, pp. 191-192.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 32.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 29.

- 1 2 Baumgardner, p. 57.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 63.

- ↑ Baumgardner, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Lindsay, pp. 192.

- 1 2 3 4 Secrest (1988), p. 18.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 71.

- ↑ Baumgardner, pp. 90–92.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 194.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 196.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 93.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 94.

- ↑ Lindsay, pp. 195-196.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 198.

- ↑ Baumgardner, pp. 95-96.

- 1 2 Lindsay, p. 201.

- ↑ Baumgardner, pp. 99-101.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 205.

- ↑ Baumgardner, p. 101.

- 1 2 Secrest (1988), p. 20.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 204.

- 1 2 Baumgardner, p. 102.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 207.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 208.

- 1 2 3 Secrest (1988), p. 21.

- ↑ Lindsay, p. 209.

- 1 2 Secrest (1988), p. 22.

- ↑ Adams & Schneider, pp. 557–596.

Bibliography

- Adams, Kevin & Schneider, Khal (1 November 2011). "'Washington is a Long Way Off': The 'Round Valley War' and the Limits of Federal Power on a California Indian Reservation". Pacific Historical Review. 80 (4): 557–596. doi:10.1525/phr.2011.80.4.557. JSTOR 10.1525/phr.2011.80.4.557.

- Baumgardner, Frank H., III (2006). Killing for Land in Early California: Indian blood at Round Valley: Founding the Nome Cult Indian Farm. New York: Algora Pub. ISBN 9780875863641.

- Bigelow, Ed; Madley, Benjamin & Johnston-Dodds, Kimberly. "California and the Indian Wars: The Mendocino War of 1859-1860". The California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Johnston-Dodds, Kimberly (September 2002). "1860: The Legislature's Majority and Minority Reports on the Mendocino War" (PDF). Early California Laws and Policies Related to California Indians. California Research Bureau, California State Library. ISBN 1587031639. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Lindsay, Brendan C (2012). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846-1873. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803240216.

- Santoro, Nicholas J. (2009). Atlas of the Indian Tribes of North America and the Clash of Cultures. New York: iUniverse, Inc. pp. 125, 299. ISBN 9781440107955.

- Secrest, William B. (1988). "Jarboe's War". Californians. 6 (6): 16–22.

- —— (2003). When the Great Spirit Died: The Destruction of the California Indians, 1850–1860 (2. pr. ed.). Sanger, CA: Word Dancer Press. ISBN 9781884995408.