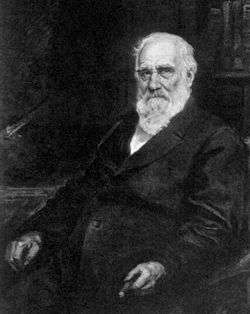

Max Joseph von Pettenkofer

Max Joseph Pettenkofer, ennobled in 1883 as Max Joseph von Pettenkofer (3 December 1818 – 10 February 1901) was a Bavarian chemist and hygienist. He is known for his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper sewage disposal.

Early life and education

Pettenkofer was born in Lichtenheim, near Neuburg an der Donau, now part of Weichering. He was a nephew of Franz Xaver (1783–1850), who from 1823 was a surgeon and apothecary to the Bavarian court and was the author of some chemical investigations on the vegetable alkaloids. He attended the Wilhelmsgymnasium, in Munich, then studied pharmacy and medicine at the Ludwig Maximilian University, where he graduated M.D. in 1845.

Career as chemist

After working under Liebig at Gießen, Pettenkofer was appointed chemist to the Munich mint in 1845. Two years later he was chosen as an extraordinary professor of chemistry at the medical faculty. In 1853 he was made a full professor and in 1865 he also became a professor of hygiene. In his earlier years he devoted himself to chemistry, both theoretical and applied, publishing papers on the preparation of gold and platinum, numerical relations between the atomic masses of analogous elements, the formation of aventurine glass, the manufacture of illuminating gas from wood, the preservation of oil paintings, among other things. The reaction known by his name for the detection of bile acids was published in 1844. In his widely used method for the quantitative determination of carbonic acid the gaseous mixture is shaken up with baryta or limewater of known strength and the change in alkalinity ascertained by means of oxalic acid. It was who provided the experimental proof that the mysterious haematinum of ancient times was in fact a copper-colored glass.[1]

Career as hygienist

Pettenkofer's name is most familiar in connection with his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper sewage disposal. His attention was drawn to this subject by the unhealthy condition in Munich in the 19th century. He was a proponent of the "ground water theory" regarding the spread of epidemic Asiatic cholera. He believed that the fermentation of organic matter in the subsoil released the cholera germ into the air which then infected the most susceptible (those with poor diet, constitution, etc.). He was not, however, a contagionist because he adhered to the belief that cholera spread through air rather than directly from human contact. This is essentially an updated theory of miasmatism.

Pettenkofer obtained bouillon laced with a large dose of Vibrio cholerae bacteria from Robert Koch, the proponent of the theory that the bacteria was the sole cause of the disease. He consumed the bouillon in a self-test in the presence of several witnesses on 7 October 1892. He also took bicarbonate of soda to neutralise his stomach acid to counter a suggestion by Koch that the acid could kill the bacteria. Pettenkofer suffered mild symptoms for nearly a week but claimed these were not associated with cholera. The modern view is that he did indeed have cholera, but was lucky to just have a mild case and he possibly had some immunity from a previous episode.[2]

Publications

Pettenkofer gave vigorous expression to his views on hygiene and disease in numerous books and papers; he was an editor of the Zeitschrift für Biologie (together with Carl von Voit) from 1865 to 1882, and of the Archiv für Hygiene from 1883 to 1894. In 1883 he was awarded a hereditary title of nobility.

Death

In 1894 he retired from active work, and on 10 February 1901 he shot himself in a fit of depression. He died at his home in the Residenz in Munich. He is buried in the Alter Südfriedhof in Munich.

References

- ↑ , M. Ueber einen antiken rothen Glasfluss (Haematinon) und über Aventurin-Glas. Abhandlungen der naturw.-techn. Commission der k. b. Akad. der Wissensch. I. Bd. München, literar.-artist. Anstalt, 1856.

- ↑ Lawrence K. Altman, Who Goes First?: The Story of Self-experimentation in Medicine, pp. 24-25, University of California Press, 1987 ISBN 0520212819.

- Attribution

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pettenkofer, Max Joseph von". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pettenkofer, Max Joseph von". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Max von Pettenkofer. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Max Joseph von Pettenkofer |

- Picture, short biography, and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Snowden, Frank (2010). "Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600: Lecture 13 — Contagionism versus Anticontagionism". Open Yale Courses. Yale University.