Mathern Palace

| Mathern Palace | |

|---|---|

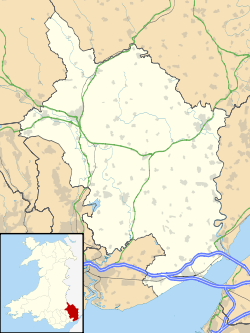

Location of Mathern Palace in Monmouthshire | |

| Location | Mathern, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Coordinates | 51°36′51″N 2°41′25″W / 51.61417°N 2.69028°WCoordinates: 51°36′51″N 2°41′25″W / 51.61417°N 2.69028°W |

| OS grid reference | ST 523 908 |

| Built |

14th – 17th centuries Restored 1894–99 |

| Architect |

Original: various Restoration: Henry Avray Tipping |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 10 June 1953 |

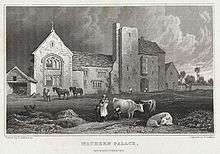

Mathern Palace is a Grade I listed building in the village of Mathern, Monmouthshire, Wales, located some 3 miles (4.8 km) south-west of Chepstow close to the Severn estuary. Between about 1408 and 1705 it was the main residence of the Bishops of Llandaff. After falling into ruination, it was restored and its gardens laid out between 1894 and 1899 by the architectural writer Henry Avray Tipping. In recent years it has been in private hands, and used as a residential centre.

History

According to the Liber Landavensis, lands at Mathern and for several miles around, as far east as the River Wye, were given to the Bishops of Llandaff by Meurig, in memory of his father Tewdrig, king of Gwent and Glywysing. Tewdrig had been wounded in a battle with the Saxons near Tintern, perhaps around the year 630, and died at Mathern; the parish church of St. Tewdric was built on the spot.[1] The bishop's residence was built nearby. It is thought that the location – some 28 miles (45 km) east of Llandaff – was chosen partly because its proximity to a well-used crossing point of the Severn estuary, and after their construction the castles at Caldicot and Chepstow gave protection against attacks from the Welsh.[2]

By 1333, Mathern was one of three medieval palaces belonging to Llandaff, the others being at Bishton and at Llandaff itself. The house was repaired after the death of bishop Rodger Cradock in 1382,[1] and after Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion in the early 15th century, in which the other two palaces were destroyed, it was the only one kept habitable.[3] The palace may have been rebuilt, at least in part, by John de la Zouch, bishop from 1408 to 1423. In 1882, local historian Octavius Morgan described three carved stones, showing symbols of the Holy Trinity, which once formed part of a grand gateway to the Palace dating from the time of de la Zouch; these had been deposited by Lord Tredegar at the museum at Caerleon.[4] There is a datestone of 1419, and the range appears to date from that period.[3]

The property may have been extended by John Marshall, bishop from 1478 to 1496, and further work – perhaps a substantial enlargement – was undertaken by Miles Salley, bishop from 1500 to 1516. The property is believed to have started to fall into disrepair during the tenure of bishop Anthony Kitchin, between 1545 and 1563. The last major renovations of the building, until the late 19th century, were undertaken by Francis Godwin, bishop between 1601 and 1617, who provided new windows in the west wing.[5][1][2] It fell out of use after the death of William Beaw, the last bishop to live there, in 1705,[5] and was partly demolished around 1770.[3] In 1794 the buildings and lands were let for farming, firstly by the Bishop and later by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. In 1801, Archdeacon Coxe reported the palace as being "in a sad state of dilapidation" while still preserving "some remains of ancient grandeur".[6]

The Ecclesiastical Commissioners sold the property in 1889 to George Carwardine Francis, a local solicitor who in turn sold the largely ruined buildings, in 1894, to the architectural writer and garden designer Henry Avray Tipping.[5] (In later years Tipping worked closely with Francis' son, the architect Eric Francis.) At Mathern, Tipping noted that:[6]

What remained of the old palace, after the lead had been stripped from the greater part of its roofs, and its interior woodwork and fittings had been destroyed or removed, [had been] turned into a farmhouse. The gatehouse, banqueting hall, and other now useless buildings provided material for barn and cowshed. The chapel was converted into a dairy, the kitchen into a stable.

Tipping decided to restore the buildings as a home for himself and his ageing mother, drawing explicitly on the guidelines on restoring old buildings that had been drawn up by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). By 1899 Tipping had restored and enlarged the house. He also laid out a new and largely informal garden around the buildings, in the Arts and Crafts style influenced by the writings of William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll. An article by Tipping in Country Life magazine in 1910 set out his approach in detail, including his protection of architectural features.[2] According to the architectural writer John Newman, "Tipping wove in his own contributions with... tact and restraint";[3] Tipping's biographer states that he "transformed it into an unpretentious, romantic country home set in a delightful garden".[6]

In 1912, after the death of his mother and last surviving brother, Tipping let Mathern Palace before selling it in 1914.[6] During the First World War it was used to house refugees from Belgium following the German invasion.[2] In 1923 it was bought by Col. D. J. C. McNabb,[1] whose widow remained there until it was sold in 1957 to steel makers Richard Thomas and Baldwins Ltd., the owners of the Llanwern steelworks 12 miles (19 km) away, for use as a guest house. After nationalisation it passed into the hands of the British Steel Corporation and then the Corus Group, a subsidiary of Tata Steel Europe.[7]

The palace was sold to private owners in August 2014, and is now marketed as an events venue, with rooms available for rent.[8]

The property

Existing buildings

The palace is approached through the remains of an early 15th century gateway, on either side of which is a cottage designed by Tipping. The main building itself has an "undemonstrative irregularity", suggesting that the bishops had relatively poor resources, and modified the building incrementally.[3] The buildings were given Grade I listed building status on 10 June 1953.[9]

Work was undertaken in 2011 to record the historic elements of the building as part of a fire safety check.[10] This showed that there are four surviving main historic elements:

- The northwest wing: This was substantially renovated by Tipping, with the floors being rebuilt to create an exposed timber ceiling. Two stone corbels bearing the crests of the Diocese of Llandaff and the Tipping family were inserted during the renovations.

- The Chapel wing or east wing: This comprises a first floor chapel, probably built by Salley in the early 16th century, and with an "impressive"[3] medieval window of four lights.

- The central section, with a series of medieval beams and joists forming an ornately decorated ceiling beneath which is a long 16th-century parlour.

- The Tower: A three storey structure above the main entrance to the building, with many unrestored medieval features including stone mullioned windows, and the remains of a garderobe chute. Parts of the tower may date from the 14th century.

Extensions to the building, including a third wing to the main building, were added by Tipping. The building's internal layout was altered by both Tipping and later owners, and is described by Newman as "hard to interpret".[3]

Gardens

The gardens lie to the north-west, south-east and south-west of the house. Tipping laid out terraces on the south-west facing slope, and converted the remains of medieval fishponds into ornamental ponds. To the south-east he laid out formal lawns, a kitchen garden, and a sunken rose garden, with the various elements being linked by limestone and grass walks flanked by walls and hedges. He incorporated ruined walls into the overall design, and built a rock garden on the steeper slope to the north-west of the house. Tipping also planted many trees and bushes, including a large circular arbour of yew on the highest terrace.[3][10][11]

Access

The property is not open to the general public,[11] but rooms are available for rent.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Davies, E. T. (1990). A History of the Parish of Mathern (2nd ed.). Mathern Parochial Church Council.

- 1 2 3 4 Gillian Reynolds, The Bishop’s Palace, Mathern, Gwent County History Association, 2006

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Newman, John (2000). The Buildings of Wales: Gwent/Monmouthshire. Penguin Books. pp. 384–386. ISBN 0-14-071053-1.

- ↑ Morgan, Octavius (1882), "Goldcliff and the Ancient Roman Inscribed Stone Found There 1878", Monmouthshire & Caerleon Antiquarian Association

- 1 2 3 Bradney, Sir Joseph (1933). A History of Monmouthshire: The Hundred of Caldicot. Mitchell Hughes and Clarke. pp. 63–67. ISBN 0 9520009 4 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Gerrish, Helena (2011). Edwardian Country Life: The Story of H. Avray Tipping. London: Frances Lincoln Ltd. pp. 84–101. ISBN 978-0-7112-3223-5.

- ↑ Corus Strip Products UK, Where Three Histories Meet, 2007

- 1 2 Mathern Palace website. Retrieved 21 November 2015

- ↑ British Listed Buildings: Mathern Palace, Mathern. Retrieved 13 September 2013

- 1 2 James Meek, Mathern Palace, Chepstow, Monmouthshire: Historic Buildings Recording, Dyfed Archaeological Trust, February 2011

- 1 2 Parks and Gardens UK, Record ID 2241: Mathern Palace, Chepstow, Wales, 27 July 2007