Mary Macarthur

| Mary Macarthur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

8 December 1880 Ayr, Scotland |

| Died |

1 January 1921 (aged 40) Golders Green, London, England |

| Known for | Women's trade unionism |

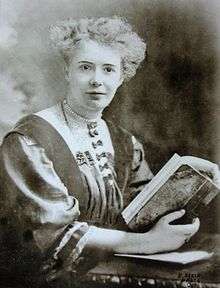

Mary Macarthur (13 August 1880 in Ayr – 1 January 1921 in Golders Green) was a trade unionist and women's rights campaigner.

Early years

Macarthur's father was the proprietor of a drapery establishment. She attended school in Glasgow and after editing the school magazine, decided she wanted to become a full-time writer. After her Glasgow schooling, she studied for some time in Germany. About 1901, Macarthur became a trade unionist after hearing a speech made by John Turner about how badly some workers were being treated by their employers. Mary became secretary of the Ayr branch of the Shop Assistants' Union, and her interest in this union led to her work for the improvement of women's labour conditions. In 1902 Mary became friends with Margaret Bondfield who encouraged her to attend the union's national conference where Macarthur was elected to the union's national executive.[1][2]

London and the Women's Trade Union League

In 1903 Macarthur moved to London where she became Secretary of the Women's Trade Union League. Active in the fight for the vote, she was totally opposed to those in the NUWSS and the WSPU who were willing to accept the franchise being given to only certain groups of women. Macarthur believed that a limited franchise would disadvantage the working class and feared that it might act against the granting of full adult suffrage.

The Women's Trade Union League united women-only unions from different trades including a mixed-class membership. The conflicting aims of activists affiliated with different classes and organisations barred the league from affiliation to the Trades Union Congress.[3]

To solve this conflict Macarthur founded the National Federation of Women Workers in 1906. The model for the Federation was a general labour union, "open to all women in unorganised trades or who were not admitted to their appropriate trade union."[3]

In general Macarthur chose the universal suffrage position over gradualist approaches both within the Trade Union movement and the Women's Rights movement. "Mary Macarthur estimated that if women were enfranchised on the same terms as men, less than 5 per cent of working women would be eligible."[3] (Tony Cliff quoting the Proceedings, National Women's Trade Union League, USA (1919), p. 29.)

Macarthur was involved in the Exhibition of Sweated Industries in 1905 and the formation of the Anti-Sweating League in 1906. The following year she founded the Women Worker, a monthly newspaper for women trade unionists.

In 1910 the women chainmakers of Cradley Heath won a battle to establish the right to a fair wage following a 10-week strike. This landmark victory changed the lives of thousands of workers who were earning little more than 'starvation wages'. Macarthur was the trade unionist who led the women chain makers in their fight for better pay. In reference to female earnings, Macarthur commented that "women are unorganised because they are badly paid, and poorly paid because they are unorganised."[4]

Cat and Mouse Act

In August 1913, in response to the government Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 whereby hunger striking prisoners would be released when too weak to be active and permitting their re-arrest as soon as they were active, Macarthur took part in a delegation to meet with the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna and discuss the Cat and Mouse Act. McKenna was unwilling to talk to them and when the women refused to leave the House of Commons, Macarthur and Margaret McMillan were physically ejected and Evelyn Sharp (suffragist) and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison.

Although an opponent of the war Macarthur nonetheless became secretary of the Ministry of Labour's central committee on women's employment.[5]

Post WWI

After the Representation of the People Act 1918 had enfranchised women over the age of thirty and the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 allowed women to stand for Parliament, Macarthur stood as Labour Party candidate in Stourbridge, Worcestershire at the General Election on 14 December 1919. She was defeated, as were most anti-war candidates.[6]

She continued her work with the Women's Trade Union League and played an important role in transforming it into the Women's section of the Trade Union Congress. Mary Macarthur died of cancer on 1 January 1921.

Legacy

In 1909 The New York Times published an article about Macarthur which bears witness to some of the divisions in the Women's movement at the time and across the Atlantic.[7]

In 1911, Macarthur married William Crawford Anderson (d. 1919), chairman of the executive committee of the Labour party, who was from 1914 to 1918 member for the Attercliffe division of Sheffield.[2]

An exhibition commemorating Macarthur is displayed in the Cradley Heath Workers' Institute, which has been rebuilt at the Black Country Living Museum.

The Mary Macarthur Scholarship Fund and Mary Macarthur Educational Trust were established in 1922 and 1968 respectively, with the aims "to advance the educational opportunities of working women".[8] Awards are made in memory of "pioneers of trade unionism",[8] Mary Macarthur, Emma Paterson, Lady Dilke and Jessie Stephen.[8] Their assets were transferred to the TUC Educational Trusts in 2010.[8]

References

- ↑ electricscotland.com

- 1 2

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Macarthur, Mary". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Macarthur, Mary". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York. - 1 2 3 , Article Class Struggle and Women's Liberation

- ↑ "What is her legacy?". bbc4.

- ↑

- ↑ , Campaign Manifesto

- ↑ "Says no to Mrs. Belmont". The New York Times. 8 October 1909.

- 1 2 3 4 "Congress 2010" (PDF). General Council Report. The 142nd annual Trades Union congress. Manchester: Trades Union Congress. September 2010. p. 137. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

Publications

- S. Boston, Women Workers and the Trade Unions (London 1980)

- M.A. Hamilton, Mary Macarthur (London 1925)

- Margaret Bondfield, A Life's Work, 1948

External links

- Cradley Women Chainmakers' Festival

- Election manifesto

- Spartacus

- Electric Scotland-Women in History of Scots Descent

- Tribune History- gloss

- Article – Margaret Bondfield and Mary Macarthur : their work to organize working women

- Mary’s Manifesto – Election Promises to Stourbridge Folk from 1918