The Tombs

- For the 2012 Clive Cussler novel, see The Tombs (novel), for the 1991 Argentine film, see The Tombs (film).

Coordinates: 40°42′59.8″N 74°00′05″W / 40.716611°N 74.00139°W

The Tombs is the colloquial name for the Manhattan Detention Complex[1] (formerly the Bernard B. Kerik Complex[2]), a municipal jail in Lower Manhattan at 125 White Street, as well as the nickname for three previous city-run jails in the former Five Points neighborhood of lower Manhattan, an area now known as the Civic Center.

The original Tombs, officially known as the Halls of Justice, was built in 1838 in the Egyptian Revival style.[1] It was a replacement for the colonial era Bridewell Prison, located in today's City Hall Park. The new structure incorporated material from the Bridewell (built in 1735 and demolished in 1838), mainly granite, to save money.[3]

The four buildings known as The Tombs were:

- Tombs I, 1838–1902, New York City Halls of Justice and House of Detention

- Tombs II, 1902–1941, City Prison

- Tombs III, 1941–1974, Manhattan House of Detention

- Tombs IV, 1983/1990–present, Manhattan Detention Complex (known as the Bernard B. Kerik Complex from 2001 to 2006)

History

Halls of Justice and House of Detention, 1838–1902

The first complex to have the nickname was completed in 1838. The design by John Haviland was allegedly inspired by a picture of an Egyptian tomb that appeared in John Lloyd Stephens' Incidents of Travel in Egypt, although this appears to be untrue.[4][5] The building was 253 feet, 3 inches in length by 200 feet, 5 inches wide and it occupied a full block, surrounded by Centre, Franklin Street, Elm (today's Lafayette), and Leonard Streets. It initially accommodated about 300 prisoners. Originally $250,000 was allocated in 1835 to build the Tombs, however various cost overruns occurred prior to completion of the project.

The building site had been created by filling in the Collect Pond, a freshwater pond that had once been the principal water source for colonial New York City. Industrialization and population density by the late 18th century resulted in the severe pollution of the Collect. It was condemned, drained and filled in by 1817. The landfill job was poorly done, and in a span of less than ten years, the ground began to subside.

The resulting swampy, foul-smelling conditions had already resulted in the quick transformation of the neighborhood into a slum known as Five Points by the time construction of the prison started in 1838. The enormous, heavy masonry of Haviland's building was built atop vertical piles of gigantic lashed hemlock tree trunks in a bid for stability, but the entire structure began to sink soon after it was opened. This damp foundation was primarily responsible for its bad reputation as being unsanitary during the decades to come.

As it also housed the city's courts, police, and detention facilities, The Tombs' formal title was The New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention. Some regarded it as a notable example of Egyptian Revival architecture in the U.S., but opinion varied greatly concerning its actual merit. "What is this dismal fronted pile of bastard Egyptian, like an enchanter's palace in a melodrama?", asked Charles Dickens in his American Notes of 1842.

The prison was well known for its corruption and was the scene of numerous scandals and successful escapes during its early history. A fire on November 18, 1842 destroyed part of the building, the same day that a notorious killer named John C. Colt was due to be hanged. Apparently this was no coincidence, but if it was an escape attempt on Colt's part, it failed. He'd fatally stabbed himself in his cell.[7] On November 22, 1872, William J. Sharkey, a convicted murderer and minor New York City politician, earned national notoriety for escaping from the prison disguised as a woman. He was never captured and his ultimate fate is unknown.[8]

As early as 1850, many people were calling for its destruction. By the early 20th century, reforms began to be made as the first prison school for younger inmates in an American adult correction facility was established by the Public Schools Association in 1900.

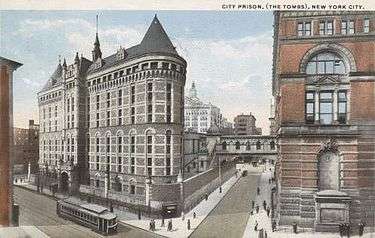

City Prison, 1902–1941

The original building was replaced in 1902. The million-dollar new City Prison featured an eight-story Châteauesque facade with conical towers along Centre Street, and was bounded by Centre, White Street, Elm (today's Lafayette), and Leonard Streets.[9]

The architects were Frederick Clarke Withers and Walter Dickson. The English Withers and Dickson, from Albany, had partnered together since the 1880s. This was their final major commission. In September 1900 the architects complained that construction would be delayed for a year, and cost an additional $250,000, due to the unnecessary insertion of corrupt Tammany Hall architects Horgan & Slattery into the project.[10]

The building connected to the 1892 Manhattan Criminal Courts Building with a "Bridge of Sighs" crossing four stories above Franklin Street. There was also an Annex, with another 144 cells, that had been finished in 1884.

Manhattan House of Detention, 1941–1974

The 1902 prison was replaced in 1941 by a new high-rise facility across the street, on the east side of Centre Street. The 795,000 square foot[11] art deco facility was designed by architects Harvey Wiley Corbett and Charles B. Meyers.[12][13]

The new facility was (and is) the northmost of the four 15-story towers of the massive New York City Criminal Courts Building, 100 Centre Street, bounded by Centre, White, and Baxter Streets, and Hogan Place. The three southern towers, which are wings of a single integrated structure sharing a five-story "crown",[14] house the city's Criminal and Supreme Courts, city offices and various departments, including the headquarters of the Department of Corrections. The northern tower is freestanding.

With the separate address of 125 White Street, the northern tower was officially named the Manhattan House of Detention for Men (MHD), although still referred to popularly as The Tombs.

By 1969 the Tombs ranked as the worst of the city's jails, both in overall conditions and in overcrowding. It held an average of 2000 inmates in spaces designed for 925.[15] After multiple warnings about falling budgets, aging facilities and rising populations, and after an informational picket of City Hall by union correctional officers drawing attention to the pressures, inmates rioted on August 10, 1970. Rioters took command of the entire ninth floor. Five officers were held hostage for eight hours, until state officials agreed to hear prisoner grievances and take no punitive action against the rioters.[16] Despite that promise, Mayor John Lindsay had the prisoners identified as primary troublemakers shipped upstate to the state's Attica Correctional Facility, an act that likely contributed to the Attica Prison riot about a year later.[17]

Within a month after the riot, the New York City Legal Aid Society filed a landmark class action suit on behalf of pretrial detainees held in the Tombs. After years of litigation, and after federal judge Morris E. Lasker agreed that the prison's conditions were so bad as to be unconstitutional, the city abruptly decided to close the Tombs on December 20, 1974 and ship the remaining 400 inmates to Rikers Island (where conditions were not much better).[18]

Manhattan Detention Complex, 1983/1990–present

As of 2014 the Manhattan Detention Complex consists of two buildings: a South Tower, the former Manhattan House of Detention, completely remodeled and reopened in 1983, and a new North Tower to the north across White Street, completed in 1990 and designed by Max O. Urbahn Associates and Litchfield-Grosfeld Associates. The entire complex still houses only male inmates, most of them pretrial detainees. The combined capacity of the two buildings is about 900 people.[19]

The current Tombs jail was named The Bernard B. Kerik Complex in December 2001 at the direction of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani;[2] Kerik had been a well-regarded[20] corrections commissioner from 1998–2000 before becoming police commissioner. After Kerik's 2006 plea bargain admitting to two misdemeanor ethics violations dating from his tenure as a city employee, Mayor Michael Bloomberg ordered his name removed.[1]

In popular culture

Film

- The Tombs and the Bridge of Sighs appears in For the Defense (1930) with William Powell

- The Tombs appear in the 1947 film noir, Kiss of Death.

- The Tombs appear in the 2000 remake of Shaft.

- Towards the end of the movie American Gangster (2007), Denzel Washington's character, Frank Lucas, is seen leaving prison after a 15-year sentence. This scene was filmed at the Tombs, although in real life prisoners are held there for relatively brief stays (arraignments, trials, etc.).

Literature and plays

- William Burroughs refers to The Tombs in his semi-autobiographical book Junkie.

- As mentioned above, Charles Dickens disparaged The Tombs' architecture in American Notes (1842).

- In his autobiographical novel Memos from Purgatory, Harlan Ellison describes his brief incarceration in The Tombs following his arrest for possession of a firearm that he had used as a prop while lecturing.[21]

- In the Wild Cards book series, edited by George R. R. Martin with assistance by Melinda Snodgrass, Jay Ackroyd often uses his wild card power to teleport his enemies to the Tombs.

- The Tombs is the setting for the endings of two works by Herman Melville: Pierre: or, The Ambiguities and Bartleby, the Scrivener. Bartleby, apparently by willful starvation, dies on the grassy ground of an open yard in the prison, prompting his former employer to famously exclaim, "Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!"

- The Tombs is the setting of the play Short Eyes by Miguel Piñero and its film adaptation.

- The Tombs provides the setting for Harry Steeger's 1937 pulp fiction story "Dictator of the Damned", in which The Spider stages a daring raid to help exonerate an innocent man.

- Eric Carter, the main character of Richard Price's novel Lush Life, is incarcerated in the Tombs.

- Front de Liberation du Quebec member Pierre Vallieres wrote White Niggers of America while incarcerated in the Tombs for manslaughter.

Music

- Jim Carroll mentions in his song "People Who Died" that his friend Bobby committed suicide by hanging while in the Tombs.

- Paul Simon's song "Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard" includes a threat from the protagonist's father of being placed in the "House of Detention."

Radio

- In November 2000, 16 people associated with the Opie and Anthony radio show were arrested and held in The Tombs overnight during a promotion for "The Voyeur Bus", a mostly glass bus carting topless women through Manhattan with a police escort.[22]

Television

- In the TV sitcom Barney Miller, the officers frequently mention that they will take an arrestee to The Tombs.

- The Tombs are featured in season 1 of the 2012 historical drama Copper on BBC America.

- The TV dramas Blue Bloods, Law & Order, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, and Castle regularly make references to The Tombs. In the SVU episode "Stranger", someone impersonating a long-missing daughter is sent to the Tombs, with the scene-change reading "MANHATTAN DETENTION COMPLEX" and the street address, as well as the usual inclusion of the calendar date.

- In the animated TV series Archer, the character Cyril mentions "spending the night in The Tombs, getting worked over by the cops" in the season 2 episode "Stage Two".

- In The Newsroom episode "Oh Shenandoah," Will McAvoy is held at the Manhattan Detention Complex as a result of his contempt citation.

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 Chan, Sewell. "Disgraced and Penalized, Kerik Finds His Name Stripped Off Jail" New York Times (July 3, 2006)

- 1 2 "Mayor Giuliani and Correction Commissioner Fraser rename the Manhattan Detention Complex 'The Bernard B. Kerik Complex'"

- ↑ Carrott, Richard G The Egyptian revival: its sources, monuments, and meaning, 1808–1858 University of California Press, 1978 ISBN 0-520-03324-8 p.165

- ↑ "Doom of the Old Tombs; Soon to be Removed to Make Way for New Prison". The New York Times (July 4, 1896)

- ↑ Carrott, Richard G. The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning, 1808-1858. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1978. p.165

- ↑ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010), AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195383867, p.80

- ↑ Kernan, J. Frank. Reminiscences of the Old Fire Laddies and Volunteer Fire Departments of New York p.220

- ↑ Walling, George W. Recollections of a New York Chief of Police. New York: Caxton Book Concern, Ltd., 1887. pp.292-296.

- ↑ http://www.nyc-architecture.com/IM-111002/110927-GON072-04.jpg

- ↑ "City Prison Alterations", New York Times, September 7, 1900

- ↑ http://www.newyorklawjournal.com/id=1202475526745/One-Month-After-Blaze-at-Key-NYC-Couthouse,-Miseries-Continue?slreturn=20140126031806

- ↑ Wolfe, Gerard R. (2003) New York, 15 Walking Tours: An Architectural Guide to the Metropolis. (New York: McGraw-Hill Professional (ISBN 0071411852 ), p.102

- ↑ Department of Citywide Administrative Services, City of New York. "Manhattan Criminal Court Building". Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ↑ http://skyscraperpage.com/cities/?buildingID=30093

- ↑ Courts, Corrections, and the Constitution: The Impact of Judicial ... edited by John J. DiIulio, page 140

- ↑ Courts, Corrections, and the Constitution: The Impact of Judicial ... edited by John J. DiIulio, page 143

- ↑ States of Siege : U.S. Prison Riots, 1971-1986, by Public Safety Research at the Urban Research Institute University of Louisville, page 26

- ↑ Courts, Corrections, and the Constitution: The Impact of Judicial ... edited by John J. DiIulio, page 149

- ↑ http://www.nyc.gov/html/doc/html/about/facilities_overview.shtml

- ↑ New York Times Topics: Kerik.

- ↑ Wilson, S. Michael (2001-07-22). "Paging Cordwainer Bird...." (Customer review of Memos from Purgatory). Amazon.com. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ↑ Rashbaum, William (2000-02-12). "Escort of Voyeur Bus Suspended by Police". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

Bibliography

- Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (2003). ""America's Greatest Criminal Barracks": The Tombs and the Experience of Criminal Justice in New York City, 1838–1897". Journal of Urban History. 29 (5): 525–554. doi:10.1177/0096144203029005002. OCLC 88513081.

- Roth, Mitchel P. (2006). Prisons and Prison Systems: A Global Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32856-5. OCLC 60835344.

Further reading

- Berger, Meyer (1983) [1942]. "The Tombs". The Eight Million: Journal of a New York Correspondent (Columbia University Press Morningside ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 23–35. ISBN 978-0-231-05710-3. OCLC 9066227. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- DeFord, Miriam Allen (1962). Stone Walls: Prisons from Fetters to Furloughs. Philadelphia: Chilton. OCLC 378834.

- Johnson, James A. (2000). Forms of Constraint: A History of Prison Architecture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02557-0. OCLC 42434965.

- Sifakis, Carl (2003). The Encyclopedia of American Prisons. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4511-2. OCLC 49225908.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Tombs. |

- New York Correction History Society timeline (includes photo)

- An early engraving by John Poppel.

- John DePol etching of a later building, 1942

- Painting of 1842 fire at The Tombs.

- "Irish in New York" site, Census of prisoners in 1860

- News story