Magnesium diboride

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| 12007-25-9 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 13118398 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.352 |

| PubChem | 15987061 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| MgB2 | |

| Molar mass | 45.93 g/mol |

| Density | 2.57 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 830 °C (1,530 °F; 1,100 K) (decomposes) |

| Structure | |

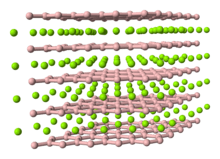

| Hexagonal, hP3 | |

| P6/mmm, No. 191 | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Magnesium diboride (MgB2) is a simple ionic binary compound that has proven to be an inexpensive and useful superconducting material.

Superconductivity

Its superconductivity was discovered by the group of Akimitsu in 2001.[1] Its critical temperature (Tc) of 39 K (−234 °C; −389 °F) is the highest amongst conventional superconductors. This material was first synthesized and its structure confirmed in 1953,[2] but its superconducting properties were not discovered until 2001.[3]

Though generally believed to be a conventional (phonon-mediated) superconductor, it is a rather unusual one. Its electronic structure is such that there exist two types of electrons at the Fermi level with widely differing behaviours, one of them (sigma-bonding) being much more strongly superconducting than the other (pi-bonding). This is at odds with usual theories of phonon-mediated superconductivity which assume that all electrons behave in the same manner. Theoretical understanding of the properties of MgB2 has almost been achieved with two energy gaps. In 2001 it was regarded as behaving more like a metallic than a cuprate superconductor.[4]

Semi-Meissner state

Using the BCS theory and the known energy gaps of the pi and sigma bands of electrons, which are 2.2 and 7.1 meV, the pi and sigma bands of electrons have been found to have two different coherence lengths, 51 nm and 13 nm.[5] The corresponding London penetration depths are 33.6 nm and 47.8 nm. This implies that the Ginzburg-Landau parameter is 0.66±0.02 and 3.68 respectively. The first is less than 1/√2 and the second is greater, therefore the first seems to indicate marginal type I superconductivity and the second type II superconductivity.

It has been predicted that when two different bands of electrons yield two quasiparticles, one of which has a coherence length that would indicate type I superconductivity and one of which would indicate type II, then in certain cases, vortices attract at long distances and repel at short distances.[6] In particular, the potential energy between vortices is minimized at a critical distance. As a consequence there is a conjectured new phase called the semi-Meissner state, in which vortices are separated by the critical distance. When the applied flux is too small for the entire superconductor to be filled with a lattice of vortices separated by the critical distance, then there are large regions of type I superconductivity, a Meissner state, separating these domains.

Experimental confirmation for this conjecture has arrived recently in MgB2 experiments at 4.2 kelvin. The authors found that there are indeed regimes with a much greater density of vortices. Whereas the typical variation in the spacing between Abrikosov vortices in a type II superconductor is of order 1%, they found a variation of order 50%, in line with the idea that vortices assemble into domains where they may be separated by the critical distance. The term type-1.5 superconductivity was coined for this state.[5]

Synthesis

Magnesium diboride can be synthesized by several routes. The simplest is by high temperature reaction between boron and magnesium powders.[4] Formation begins at 650 °C; however, since magnesium metal melts at 652 °C, the reaction mechanism is considered to be moderated by magnesium vapor diffusion across boron grain boundaries. At conventional reaction temperatures, sintering is minimal, although enough grain recrystallization occurs to permit Josephson quantum tunnelling between grains.

Superconducting magnesium diboride wire can be produced through the powder-in-tube (PIT) ex situ and in situ processes as it was presented by Prof. Bartek Glowacki in April 2001.[7] In the in situ variant, a mixture of boron and magnesium is poured into a metal tube, which is reduced in diameter by conventional wire drawing. The wire is then heated to the reaction temperature to form MgB2 inside. In the ex situ variant, the tube is filled with MgB2 powder, reduced in diameter, and sintered at 800 to 1000 °C. In both cases, later hot isostatic pressing at approximately 950 °C further improves the properties.

In 2003, a new and easy in situ technique for the synthesis of MgB2 was presented by Giunchi et al. (Edison S.p.A.).[8] This new technique employs reactive liquid infiltration of magnesium inside a granular preform of boron powders and was called Mg-RLI technique. The method allowed the manufacture of both high density (more than 90% of the theoretical density for MgB2) bulk materials and special hollow fibers. This method is equivalent to similar melt growth based methods such as the Infiltration and Growth Processing method used to fabricate bulk YBCO superconductors where the non-superconducting Y2Ba1Cu1O5 is used as granular preform inside which YBCO based liquid phases are infiltrated to make superconductive YBCO bulk. This method has been copied and adapted for MgB2 superconductor and rebranded as Reactive Mg Liquid Infiltration. The process of Reactive Mg Liquid Infiltration in a boron preform to obtain MgB2 has been a subject of patent applications by Edison S.p.A. (Italy).

Hybrid physical-chemical vapor deposition (HPCVD) has been the most effective technique for depositing magnesium diboride (MgB2) thin films.[9] The surfaces of MgB2 films deposited by other technologies are usually rough and non-stoichiometric. In contrast, the HPCVD system can grow high-quality in situ pure MgB2 films with smooth surfaces, which are required to make reproducible uniform Josephson junctions, the fundamental element of superconducting circuits.

Electromagnetic properties

Properties depend greatly on composition and fabrication process. Many properties are anisotropic due to the layered structure. 'Dirty' samples, e.g., with oxides at the crystal boundaries, are different from 'clean' samples.[10]

- The highest superconducting transition temperature Tc is 39 K.

- MgB2 is a type-II superconductor, i.e. increasing magnetic field gradually penetrates into it.

- Maximum critical current (Jc) is: 105 A/m2 at 20 T, 106 A/m2 at 18 T, 107 A/m2 at 15 T, 108 A/m2 at 10 T, 109 A/m2 at 5 T.[10]

- As of 2008 : Upper critical field (Hc2): (parallel to ab planes) is ~14.8 T, (perpendicular to ab planes) ~3.3 T, in thin films up to 74 T, in fibers up to 55 T.[10]

Improvement by doping

Various means of doping MgB2 with carbon (e.g. using 10% malic acid) can improve the upper critical field and the maximum current density[11][12] (also with polyvinyl acetate[13]).

5% doping with carbon can raise Hc2 from 16 T to 36 T whilst lowering Tc only from 39 K to 34 K. The maximum critical current (Jc) is reduced, but doping with TiB2 can reduce the decrease.[14] (Doping MgB2 with Ti is patented.[15])

The maximum critical current (Jc) in magnetic field is enhanced greatly (approx double at 4.2 K) by doping with ZrB2.[16]

Even small amounts of doping lead both bands into the type II regime and so no semi-Meissner state may be expected.

Thermal conductivity

MgB2 is a multi-band superconductor, that is each Fermi surface has different superconducting energy gap. For MgB2, sigma bond of boron is strong, and it induces large s-wave superconducting gap, and pi bond is weak and induces small s-wave gap.[17] The quasiparticle states of the vortices of large gap are highly confined to the vortex core. On the other hand, the quasiparticle states of small gap are loosely bound to the vortex core. Thus they can be delocalized and overlap easily between adjacent vortices.[18] Such delocalization can strongly contribute to the thermal conductivity, which shows abrupt increase above Hc1.[17]

Possible applications

Superconductors

Superconducting properties and low cost make magnesium diboride attractive for a variety of applications.[19] For those applications, MgB2 powder is compressed with silver metal (or 316 stainless steel) into wire and sometimes tape via the PIT process.

In 2006 a 0.5 tesla open MRI superconducting magnet system was built using 18 km of MgB2 wires. This MRI used a closed-loop cryocooler, without requiring externally supplied cryogenic liquids for cooling.[20][21]

"...the next generation MRI instruments must be made of MgB2 coils instead of NbTi coils, operating in the 20–25 K range without liquid helium for cooling. ... Besides the magnet applications MgB2 conductors have potential uses in superconducting transformers, rotors and transmission cables at temperatures of around 25 K, at fields of 1 T."[19]

The IGNITOR tokamak is designed to use MgB2 for its poloidal coils.[22]

Thin coatings can be used in superconducting radio frequency cavities to minimize energy loss and reduce the inefficiency of liquid helium cooled niobium cavities.

Because of the low cost of its constituent elements, MgB2 has promise for use in superconducting low to medium field magnets, electric motors and generators, fault current limiters and current leads.

Propellants, explosives, pyrotechnics

Unlike elemental boron whose combustion is incomplete through the glassy oxide layered impeding oxygen diffusion, magnesium diboride burns completely when ignited in oxygen or in mixtures with oxidizers.[23] Thus magnesium boride has been proposed as fuel in ram jets,.[24] In addition the use of MgB2 in blast-enhanced explosives [25] and propellants has been proposed for the same reasons. Most recently it could be shown that decoy flares containing magnesium diboride/Teflon/Viton display 30–60% increased spectral efficiency, Eλ (J g−1sr−1), compared to classical Magnesium/Teflon/Viton(MTV) payloads.[26]

References

- ↑ Nagamatsu, Jun; Nakagawa, Norimasa; Muranaka, Takahiro; Zenitani, Yuji; Akimitsu, Jun (2001). "Superconductivity at 39 K in magnesium diboride". Nature. 410 (6824): 63–4. Bibcode:2001Natur.410...63N. doi:10.1038/35065039. PMID 11242039.

- ↑ Jones, Morton E. & Marsh, Richard E. (1954). "The Preparation and Structure of Magnesium Boride, MgB2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (5): 1434. doi:10.1021/ja01634a089.

- ↑ Nagamatsu, Jun; Nakagawa, Norimasa; Muranaka, Takahiro; Zenitani, Yuji; Akimitsu, Jun (2001). "Superconductivity at 39 K in magnesium diboride". Nature. 410 (6824): 63–4. Bibcode:2001Natur.410...63N. doi:10.1038/35065039. PMID 11242039.

- 1 2 Larbalestier, D. C.; Cooley, L. D.; Rikel, M. O.; Polyanskii, A. A.; Jiang, J.; Patnaik, S.; Cai, X. Y.; Feldmann, D. M.; et al. (2001). "Strongly linked current flow in polycrystalline forms of the superconductor MgB2". Nature. 410 (6825): 186–189. arXiv:cond-mat/0102216

. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..186L. doi:10.1038/35065559. PMID 11242073.

. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..186L. doi:10.1038/35065559. PMID 11242073. - 1 2 Moshchalkov, V. V.; Menghini, Mariela; Nishio, T.; Chen, Q.; Silhanek, A.; Dao, V.; Chibotaru, L.; Zhigadlo, N.; Karpinski, J.; et al. (2009). "Type-1.5 Superconductors". Physical Review Letters. 102 (11): 117001. arXiv:0902.0997

. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102k7001M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.117001. PMID 19392228.

. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102k7001M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.117001. PMID 19392228. - ↑ Babaev, Egor & Speight, Martin (2005). "Semi-Meissner state and neither type-I nor type-II superconductivity in multicomponent systems". Physical Review B. 72 (18): 180502. arXiv:cond-mat/0411681

. Bibcode:2005PhRvB..72r0502B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.72.180502.

. Bibcode:2005PhRvB..72r0502B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.72.180502. - ↑ B.A.Glowacki, M.Majoros, M.Vickers, J.E.Evetts, Y.Shi and I.McDougall, Superconductivity of powder-in-tube MgB2 wires, Superconductor Science and Technology, 14 (4) 193 (April 2001) | DOI: 10.1088/0953-2048/14/4/304

- ↑ Giunchi, G.; Ceresara, S.; Ripamonti, G.; Chiarelli, S.; Spadoni, M.; et al. (6 August 2002). "MgB2 reactive sintering from elements". IEEE Transaction on Applied Superconductivity. 13 (2): 3060–3063. doi:10.1109/TASC.2003.812090.

- ↑ Xi, X.X.; Pogrebnyakov, A.V.; Xu, S.Y.; Chen, K.; Cui, Y.; Maertz, E.C.; Zhuang, C.G.; Li, Qi; Lamborn, D.R.; Redwing, J.M.; Liu, Z.K.; Soukiassian, A.; Schlom, D.G.; Weng, X.J.; Dickey, E.C.; Chen, Y.B.; Tian, W.; Pan, X.Q.; Cybart, S.A.; Dynes, R.C.; et al. (14 February 2007). "MgB2 thin films by hybrid physical-chemical vapor deposition". Physica C. 456: 22–37. Bibcode:2007PhyC..456...22X. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2007.01.029.

- 1 2 3 Eisterer, M (2007). "Magnetic properties and critical currents of MgB2". Superconductor Science and Technology. 20 (12): R47. Bibcode:2007SuScT..20R..47E. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/20/12/R01.

- ↑ Hossain, M S A; et al. (2007). "Significant enhancement of Hc2 and Hirr in MgB2+C4H6O5 bulks at a low sintering temperature of 600 °C". Superconductor Science and Technology. 20 (8): L51. Bibcode:2007SuScT..20L..51H. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/20/8/L03.

- ↑ Yamada, H; Uchiyama, N; Matsumoto, A; Kitaguchi, H; Kumakura, H (2007). "The excellent superconducting properties of in situ powder-in-tube processed MgB2 tapes with both ethyltoluene and SiC powder added". Superconductor Science and Technology. 20 (6): L30. Bibcode:2007SuScT..20L..30Y. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/20/6/L02.

- ↑ Vajpayee, A; Awana, V; Balamurugan, S; Takayamamuromachi, E; Kishan, H; Bhalla, G (2007). "Effect of PVA doping on flux pinning in Bulk MgB2". Physica C: Superconductivity. 466: 46–50. arXiv:0708.3885

. Bibcode:2007PhyC..466...46V. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2007.05.046.

. Bibcode:2007PhyC..466...46V. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2007.05.046. - ↑ "MgB2 Properties Enhanced by Doping with Carbon Atoms". Azom.com. June 28, 2004.

- ↑ Zhao, Yong et al. "MgB2—based superconductor with high critical current density, and method for manufacturing the same" U.S. Patent 6,953,770, Issue date: Oct 11, 2005

- ↑ Ma, Y. (2006). "Doping effects of ZrC and ZrB2 in the powder-in-tube processed MgB2 tapes". Chinese Science Bulletin. 51 (21): 2669–2672. doi:10.1007/s11434-006-2155-4.

- 1 2 Sologubenko, A. V.; Jun, J.; Kazakov, S. M.; Karpinski, J.; Ott, H. R. (2002). "Thermal conductivity of single crystalline MgB2". Physical Review B. 66: 14504. arXiv:cond-mat/0201517

. Bibcode:2002PhRvB..66a4504S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.66.014504.

. Bibcode:2002PhRvB..66a4504S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.66.014504. - ↑ Nakai, Noriyuki; Ichioka, Masanori; MacHida, Kazushige (2002). "Field Dependence of Electronic Specific Heat in Two-Band Superconductors". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 71: 23. arXiv:cond-mat/0111088

. Bibcode:2002JPSJ...71...23N. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.71.23.

. Bibcode:2002JPSJ...71...23N. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.71.23. - 1 2 Vinod, K; Kumar, R G Abhilash; Syamaprasad, U (2007). "Prospects for MgB2 superconductors for magnet application". Superconductor Science and Technology. 20: R1–R13. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/20/1/R01.

- ↑ "First MRI system based on the new Magnesium Diboride superconductor" (PDF). Columbus Superconductors. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ↑ Braccini, Valeria; Nardelli, Davide; Penco, Roberto; Grasso, Giovanni (2007). "Development of ex situ processed MgB2 wires and their applications to magnets". Physica C: Superconductivity. 456 (1–2): 209–217. Bibcode:2007PhyC..456..209B. doi:10.1016/j.physc.2007.01.030.

- ↑ Ignitor fact sheet

- ↑ Koch, E.-C.; Weiser, V. and Roth, E. (2011), Combustion behaviour of Binary Pyrolants based on Mg, MgH2, MgB2, Mg3N2, Mg2Si and Polytetrafluoroethylene, EUROPYRO 2011, Reims, France

- ↑ Ward, J. R. "MgH2 and Sr(NO3)2 pyrotechnic composition" U.S. Patent 4,302,259, Issued: November 24, 1981.

- ↑ Wood, L.L. et al. "Light metal explosives and propellants" U.S. Patent 6,875,294, Issued: April 5, 2005

- ↑ Koch, Ernst-Christian; Hahma, Arno; Weiser, Volker; Roth, Evelin; Knapp, Sebastian (2012). "Metal-Fluorocarbon Pyrolants. XIII: High Performance Infrared Decoy Flare Compositions Based on MgB2 and Mg2Si and Polytetrafluoroethylene/Viton®". Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics. 37 (4): 432. doi:10.1002/prep.201200044.

External links

- Essential Science Indicators on MgB2 (1992 – May 2002)

- Old material makes a new debut, US Department of Energy Research News, 2001