Lyttelton road tunnel

.jpg) The Lyttelton tunnel portal at the southern end | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Christchurch |

| Coordinates | 43°35′39″S 172°42′42″E / 43.5942°S 172.7116°E |

| Status | Open |

| Route |

|

| Operation | |

| Opened | 27 February 1964 |

| Owner | NZ Transport Agency |

| Traffic | 10,755 (2010) |

| Toll | nil |

| Technical | |

| Length | 1,970 metres (6,460 ft) |

| Number of lanes | two |

| Operating speed | 50 km/h |

The Lyttelton road tunnel runs beneath the Port Hills to the south of the New Zealand city of Christchurch and links the city with its seaport, Lyttelton. It opened in 1964 and carries just over 10,000 vehicles per day as part of State Highway 74.[1] At 1,970 metres (6,460 ft), it is the longest road tunnel in New Zealand,[1] but will be superseded in 2017 by the Waterview Tunnels.

While the tunnel itself was not damaged due to the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake, the Heathcote tunnel canopy was destroyed. The nearby Tunnel Control Building — a Category I heritage building — suffered significant damage and was closed, before finally being demolished in 2013. Construction of a new control building was completed in 2014.[2]

History

Lyttelton and Christchurch have been linked by a rail tunnel since 1867.[3] However road transport was restricted to routes over the Port Hills, either via Evans Pass or the Sign of the Kiwi.[4]

Construction of the road tunnel started in 1962[5] and was completed in 1964 at a cost of £2.7 million.[2] When it officially opened on 27 February 1964[6] it was hailed by the local community as "the new gateway for the Port to the Plains" and a significant development in the history of the region.[2] A 20 cent toll levied to use the tunnel was abolished by the Christchurch-Lyttelton Road Tunnel Authority Dissolution Act 1978, which became effective on 1 April 1979.[7]

The original Lyttelton Road Tunnel Administration Building, designed by Christchurch architect Peter Beaven, was a Category I listed heritage building and one of the youngest buildings recognised by the trust.[8] Following its demolition as a result of damage sustained in the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake, a new control building, constructed to 180% of the Building Code to withstand future earthquakes, was completed in 2014 at a cost of $1.5 million.[2]

As of 2010, the tunnel has an AADT (average daily traffic volume) of 10,755 vehicles/day, of which 12.3% are heavy goods vehicles.[9]

Cyclists are not allowed to use the tunnel, although for many years they were allowed to pass through on one day a year. For example, the 2001 tunnel ride was held in conjunction with the 3rd NZ Cycling Conference.[10] However, since 2007 Christchurch buses have been equipped with bicycle carriers to allow cyclists' access between Heathcote and Lyttelton.[11]

Incidents

In August 2008, the tunnel was closed to northbound traffic due a landslide in bad weather conditions.[12] The tunnel was also closed temporarily following the 2010 Canterbury earthquake and subsequent aftershocks to allow for structural integrity inspections to take place. Service generally resumed within 20 minutes of each aftershock.[13]

The tunnel was again closed following the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake.[14] The tunnel canopy was severely damaged by rockfall and was demolished within days.[15] Following initial engineers' inspection the tunnel reopened to emergency vehicles later the same day.[16] Access was limited to Lyttelton residents only from 26 February before fully reopening.[17] The Tunnel Control Building was also badly damaged and deemed unfit for occupation.[18]

Images

- Lyttelton road tunnel

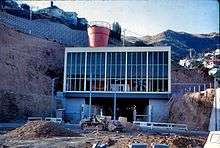

Southern (Lyttelton) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel under construction in 1964

Southern (Lyttelton) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel under construction in 1964.jpg) Northern (Heathcote) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel in 2010

Northern (Heathcote) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel in 20101.jpg) Southern (Lyttelton) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel in 2010

Southern (Lyttelton) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel in 2010.jpg) Inside Northern (Heathcote) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel in 2010

Inside Northern (Heathcote) portal of the Lyttelton road tunnel in 2010 Northern portal from the Bridle Path, May 2010

Northern portal from the Bridle Path, May 2010

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lyttelton Road Tunnel. |

- 1 2 "Our bridges and structures". NZ Transport Agency. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Triple celebration for Lyttelton Tunnel". NZ Transport Agency. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ "The Lyttelton Rail Tunnel". Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Wilson, John (30 July 2010). "Christchurch–Lyttelton road tunnel". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Walrond, Carl (5 March 2010). "Lyttelton road tunnel toll gates". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "At the opening of Lyttelton road tunnel". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Christchurch-Lyttelton Road Tunnel Authority Dissolution Act 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Transport. p. 2. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Lyttelton Road Tunnel Administration Building". Register of Historic Places. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Wen, Gerald (May 2011). "State Highway Traffic Data Booklet : 2006-2010" (PDF). NZ Transport Agency. p. 41. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "NZ Cycling Conference 2001: Transport for Living". Christchurch City Council. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Bike-carrying racks on more bus routes from November". Environment Canterbury. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Lyttelton Tunnel fully open". Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ↑ "Quake: Treasury says cost has doubled". The Dominion Post. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Christchurch quake: latest info". Stuff.co.nz. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Harper, Paul (28 February 2011). "Christchurch earthquake: What you need to know". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Lyttelton Tunnel re-opened for emergency vehicles". NZTA media release. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Lyttelton Tunnel open for use by local residents". NZTA media release. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Christchurch earthquake: Lyttelton Tunnel set to reopen". NZ Herald. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.