Moon Treaty

| Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies | |

|---|---|

|

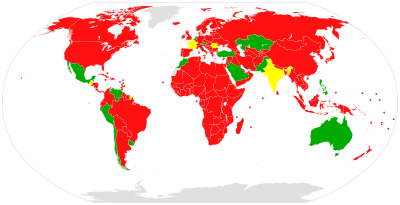

Ratifications and signatories of the treaty Parties

Signatories

Non-parties | |

| Signed | December 18, 1979 |

| Location | New York, USA |

| Effective | July 11, 1984 |

| Condition | 5 ratifications |

| Signatories | 11 |

| Parties | 17[1][2] (as of November 2016) |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Languages | English, French, Russian, Spanish, Arabic and Chinese |

|

| |

| International ownership treaties |

|---|

The Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies,[3] better known as the Moon Treaty or Moon Agreement, is an international treaty that turns jurisdiction of all celestial bodies (including the orbits around such bodies) over to the international community. Thus, all activities must conform to international law, including the United Nations Charter.

In practice it is a failed treaty because it has not been ratified by any state that engages in self-launched manned space exploration or has plans to do so (e.g. the United States, the larger part of the member states of the European Space Agency, Russia (former Soviet Union), People's Republic of China, Japan, and India) since its creation in 1979, and thus has a negligible effect on actual spaceflight. As of November 2016, it has been ratified by 17 states.[1]

Provisions

As a follow-on to the Outer Space Treaty, the Moon Treaty intended to establish a regime for the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies similar to the one established for the sea floor in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The treaty would apply to the Moon and to other celestial bodies within the Solar System, other than Earth, including orbits around or other trajectories to or around them.

The treaty makes a declaration that the Moon should be used for the benefit of all states and all peoples of the international community. It also expresses a desire to prevent the Moon from becoming a source of international conflict. To those ends the treaty does the following:

- Bans any military use of celestial bodies, including weapon testing or as military bases.

- Bans all exploration and uses of celestial bodies without the approval or benefit of other states under the common heritage of mankind principle (article 11).

- Requires that the Secretary-General must be notified of all celestial activities (and discoveries developed thanks to those activities).

- Declares all states have an equal right to conduct research on celestial bodies.

- Declares that for any samples obtained during research activities, the state that obtained them must consider making part of it available to all countries/scientific communities for research.

- Bans altering the environment of celestial bodies and requires that states must take measures to prevent accidental contamination.

- Bans any state from claiming sovereignty over any territory of celestial bodies.

- Bans any ownership of any extraterrestrial property by any organization or person, unless that organization is international and governmental.

- Requires an international regime be set up to ensure safe and orderly development and management of the resources and sharing of the benefits from them.

Ratification

The treaty was finalized in 1979 and entered into force for the ratifying parties in 1984. As of November 2016, 17 states are parties to the treaty,[1] seven of which ratified the agreement and the rest acceded.[1][4] Four additional states have signed but not ratified the treaty.[1][4] The L5 Society and others successfully opposed ratification of the treaty by the United States Senate.[5]

The objection to the treaty by the spacefaring nations is held to be the requirement that extracted resources (and the technology used to that end) must be shared with other nations. The similar regime in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is believed to impede the development of such industries on the seabed.[6]

List of parties

| State[1][2] | Signed | Deposited | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

7 Jul 1986 | Accession | |

| |

21 May 1980 | 11 Jun 1984 | Ratification |

| |

29 Jun 2004 | Accession | |

| |

3 Jan 1980 | 12 Nov 1981 | Ratification |

| |

11 Jan 2001 | Accession | |

| |

28 Apr 2014 | Accession | |

| |

12 Apr 2006 | Accession | |

| |

11 Oct 1991 | Accession | |

| |

25 Jul 1980 | 21 Jan 1993 | Ratification |

| |

27 Jan 1981 | 17 Feb 1983 | Ratification |

| |

27 Feb 1986 | Accession | |

| |

23 Jun 1981 | 23 Nov 2005 | Ratification |

| |

23 Apr 1980 | 26 May 1981 | Ratification |

| |

18 Jul 2012 | Accession | |

| |

29 Feb 2012[7] | Accession | |

| |

1 Jun 1981 | 9 Nov 1981 | Ratification |

| |

3 Nov 2016 | Accession |

List of signatories

| State[1][2] | Signed |

|---|---|

| |

29 Jan 1980 |

| |

20 Nov 1980 |

| |

18 Jan 1982 |

| |

17 Apr 1980 |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- 1 2 3 "Agreement governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". United Nations. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ↑ Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, Dec. 5, 1979, 1363 U.N.T.S. 3

- 1 2 Status of international agreements relating to activities in outer space as at 1 January 2008 United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, 2008

- ↑ Chapter 5: O'Neills Children, Reaching for the High Frontier, The American Pro-Space Movement 1972-84, by Michael A. G. Michaud, National Space Society.

- ↑ Listner, Michael (24 October 2011). "The Moon Treaty: failed international law or waiting in the shadows?". The Space Review. 9 October 2015.

Assuming that the Moon Treaty has no legal effect because of the non-participation of the Big Three is folly. The shadow of customary law and its ability to creep into the vacuum left vacant by treaty law should not be underestimated. To that end, the most effective way of dealing with the question of the Moon Treaty’s validity is to officially denounce it. However, the realities of international politics and diplomacy will likely preclude such an action. The alternative is to act in a manner contrary to the Moon Treaty, and more importantly not to act in conformity with its precepts and hope that is sufficient to turn back the shadows of the Moon Treaty.

- ↑ "Reference: C.N.124.2012.TREATIES-2 (Depositary Notification)" (PDF). New York, NY: United Nations. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Treaty Text — "Agreement Governing The Activities Of States On the Moon And Other Celestial Bodies" (1979)

- Official Treaty Site — United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), including versions of the treaty in several languages: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish.