Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen

The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (LLLL), commonly known as the "Four L", was a company union found in the United States during World War I in 1917 by the War Department as a counter to the Industrial Workers of the World.

Organizational History

Establishment

In October 1917 Colonel Brice P. Disque was dispatched to the Pacific Northwest to investigate the reasons behind what was deemed an inadequate supply of spruce for the Division of Military Aeronautics of the War Department.[1] A career Army officer, Disque had resigned his commission in 1916 to become a prison warden in the state of Michigan before rejoining the Army during the war to work as a "trouble shooter" on military procurement problems.[1]

The summer of 1917 had seen a widespread lumber strike throughout the Pacific Northwest led in part by the radical Industrial Workers of the World. Despite a decision to end the work stoppage in the lumber strike, by September shipments of spruce — a strong and flexible wood urgently needed for the production of military aircraft — had risen only to 2.6 million board feet per month, a fraction of the 10 million board feet required.[2] Col. Disque met with industry leaders in Seattle upon his arrival before setting out on a 10-day tour of lumber operations in the region.[2]

Noting the ongoing labor difficulties in the region, Disque determined to establish a special military division to be dispatched to lumber camps as needed, thereby undercutting any residual difficulties which might be presented by recalcitrant union workers.[2] Disque made efforts to win support for his decision to militarize the timber industry by gathering together a select circle of industry leaders at a meeting held at the Benson Hotel in Portland, Oregon towards the end of the month.[2]

On November 2, Disque returned to Washington, DC to win approval for his plan from Wilson administration officials, including Secretary of War Newton D. Baker.[2] Disque's plan was rapidly approved and 100 officers were committed to the effort to put the Pacific Northwest lumber industry under military control.[3]

A major meeting was held in Centralia, Washington in November bringing together representatives of 16 of the region's largest lumber companies, who were persuaded to sponsor units of a new labor-centered organization that was part and parcel of the attempt to end labor strife through militarization.[4] This new organization was to be known as the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (LLLL) — commonly known as the "Four Ls."[3] The first local of this new organization was founded in Wheeler, Oregon on November 30, 1917.[3]

Lieutenant Maurice E. Crumpacker of the US Army Signal Corps was sent on the road to various lumber camps and mills of Washington and Oregon to administer a loyalty oath to the workers there, the sole act required for membership in the LLLL.[3] These signed pledges read in part:

I, the undersigned, ...do hereby solemnly pledge my efforts during the war to the United States of America and will support and defend this country against enemies foreign and domestic.

I further swear...to faithfully perform my duty toward this company by directing my best efforts, in every way possible, to the production of logs and lumber for the construction of Army airplanes and ships to be used against our common enemies. That I will stamp out any sedition or acts of hostility against the United States Government which may come within my knowledge, and I will do every act and thing which will in general aid in carrying this war to a successful conclusion.[5]

Failure to take this loyalty oath could be met with discharge from employment and even arrest.[6]

Next to the loyalty-pledged civilian workers, a total of 25,000 soldiers were committed to work in the logging camps and mills of the Pacific Northwest over the next year in the so-called Spruce Production Division.[7] Soldiers in the camps and mills received civilian pay for their efforts, with the Army paying the minimal base salary given to all soldiers with the logging or mill contractors making up the difference.[8] Troops lived under military discipline throughout.[7]

Headquarters for the division was based at the Vancouver Barracks, just across the Columbia River from Portland, Oregon.[7]

As historian Tom Copeland notes:

With free membership and heavy pressure from fellow workers, the loggers found it difficult to turn down the Four L's and few dared to risk it. Twenty thousand members signed up during the last two months of 1917.[4]

Development

Despite the rather vague form of the LLLL, an effort was made to give the organization some of the basic forms of an industrial union. After gaining the signed pledges of workers, the military "officer-organizers" would see that civilian members were gathered into "locals" — groups which elected grievance committees which were nominally responsible for the mediation of problems in the woods or the mill with owners and bosses.[7] In the view of at least one historian this function seems to have been only of minimal effectiveness in practice, however, since "in the early months, the only real function of the local was to meet production quotas, perhaps manage a suggestion box, and be a display counter of pledged patriots."[7] Indeed, at the time of its inception Disque did not envision the LLLL as a union of any kind, but rather a loose patriotic society.[7]

In was not until late in the summer of 1918, in the waning months of the European war, that a conference of LLLL district representatives was convened in Portland to establish a formal constitution for the organization — a document drafted in advance by Disque and his assistants.[7]

According to the 1918 constitution, each local was to elect delegates to district boards, which would each choose employer and employee delegates to the "Headquarters Council," over which Disque maintained executive control.[7] The constitution further stipulated that each local was to elect a "conference committee" in charge of carrying grievances to the employer and negotiating their amelioration.[9]

Owing to its lack of dues and near mandatory status, the LLLL grew rapidly. Within six months of its establishment some 80,000 workers had taken the organization's pledge, rising to nearly 100,000 civilian workers in 1918.[10]

The syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World found itself isolated and submerged by the massive new de facto company union,[9] with repression of some of its leading activists adding to the IWW's difficult organizational situation. The rival American Federation of Labor — a lesser force in this industry at this time — found its position no better despite union head Samuel Gompers's initial endorsement of the Loyal Legion.[11] Organizers for the AF of L complained that the officer-organizers of the LLLL banned them from speaking, broke up union organizing meetings, and ejected them from the camps.[11]

In fact, most adherents of the IWW and the American Federation of Labor's Timber Workers Union seem to have ultimately joined the Loyal Legion, despite its status as a de facto "company union."[11]

An additional reason for the Loyal Legion's hegemony during the war related to its leading role on the issue of the 8-hour day — a major goal of American workers for decades. In February 1918 Col. Disque established a committee of 25 prominent lumbermen in Portland and charged them with devising an agreement to establishing the 8-hour day in the lumber industry.[12] Pressure from Disque and the Wilson administration in Washington — the chief consumer of finished goods — was instrumental in ensuring a positive outcome, and the marathon session of lumbermen eventually yielded fruit. On the morning of March 1, 1918, Disque announced the adoption of the 8-hour day to the press.[12]

At the end of the war the Loyal Legion was represented by over 1000 locals organized into 12 districts.[11] From the US government's perspective the organization was a massive success, with production of spruce boosted to more than 20 million board-feet per month.[11]

The Loyal Legion after the war

The LLLL, seen as a model institution of class collaboration, survived after the termination of World War I in November 1918 — having largely ameliorated the bitter strife between workers and capitalists that had swept the industry over previous years. The organization was seen as something of value by both sides of the production process.

Two conventions were held in December 1918, one in Portland, participated in by the 8 districts of Western Oregon and Washington, and another in Spokane, including the four districts spread across the so-called Inland Empire of Central and Eastern Washington state.[13] These conventions elected a new civilian board of executives and began the work of preparing a permanent constitution.[13]

The new constitution provided for annual conventions for each of the 12 districts, to which each local was to elect one worker delegate and one employer delegate.[13] The president of the organization or any member of the board of directors was to preside over each of these gatherings.[13] The board of directors was to serve as the decision-making authority in the case of disagreements which could not be resolved.[13]

The LLLL provided a variety of membership services. No fewer than 5 of the 12 district offices maintained free employment agencies for workers seeking employment.[14] In many other towns around the region, the Loyal Legion maintained social halls, providing recreational opportunities for workers.[14] The reforms of the war period were defended as best they were able by the board of directors through traveling inspectors, although these did not retain the same sort of authority wielded by the officer-organizers of the military during wartime.[14] From 1926, the board of directors negotiated a group insurance plan for sickness or on-the-job accidents covering LLLL members.[15]

Termination and legacy

Over time participation in the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen declined, replaced by other more aggressive labor organizations. The LLLL was finally terminated in 1938.[16]

The group is remembered by historians for the role it played in helping to end the major influence of the Industrial Workers of the World in the lumber industry of the Pacific Northwest. It was, as historian Robert L. Tyler has recalled, the "carrot" of ameliorative reform that accompanied the "stick" of violence and deportation used against the IWW in the Western timber industry:

The Loyal Legion...undercut the IWW quite effectively. In the summer of 1917, the IWW appeared to control an entire industry, but by the end of the war, the IWW was not only suppressed, it had been dispersed and absorbed.... In the minds of all but the most dedicated Wobblies the ferocious ideas of the class struggle evaporated in the atmosphere of patriotism, the eight-hour day, and palpable improvements of living conditions. The Wobblies of hard revolutionary substance had to be driven with the club rather than led by the carrot.[17]

In the view of historian Harold M. Hyman, the 4L was a largely spontaneous entity, not the product of "deliberate academic estimations conducted in a sober committee room," but rather a "reflexive, unplanned, and opportunistic creation."[18] Hyman depicts the Loyal Legion as a manifestation of "a kind of Progressivism in khaki" — an example of the Wilson administration's willingness to use government intervention to rationalize the competitive struggle that was part and parcel of capitalism.[19]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Robert L. Tyler, Rebels of the Woods: The IWW in the Pacific Northwest. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Books, 1967; pg. 101.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 102.

- 1 2 3 4 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 103.

- 1 2 Tom Copeland, The Centralia Tragedy of 1919: Elmer Smith and the Wobblies. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993; pg. 31.

- ↑ Quoted in Cloice R. Howd, Industrial Relations in the West Coast Lumber Industry. Bulletin No. 349. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, 1924; pg. 78.

- ↑ "Loggers Arrested on Marble Creek: Aliens Refuse to Take Oath of Loyal Legion and Are Apprehended," Spokane Spokesman-Review, vol. 35, no. 352 (May 1, 1918), pg. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 104.

- ↑ Harold M. Hyman, Soldiers and Spruce: Origins of the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen. Los Angeles: Institute of Industrial Relations, University of California, 1963; pg. 118.

- 1 2 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 105.

- ↑ Nancy Gentile Ford, The Great War and America: Civil-Military Relations during World War I. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2008; pg. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 109.

- 1 2 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 112.

- 1 2 3 Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 113.

- ↑ Four L Lumber News, July 1926, pg. 13, cited in Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 113.

- ↑ The Origins of the Loyal Legion of Loggers & Lumbermen: The Origins of the World’s Largest Company Union and How it Conducted Business, Seattle General Strike Project, directed by James Gregory and sponsored by the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies at the University of Washington, 1999.

- ↑ Tyler, Rebels of the Woods, pg. 115.

- ↑ Hyman, Soldiers and Spruce, pg. 13.

- ↑ Hyman, Soldiers and Spruce, pp. 15-16.

Official organ

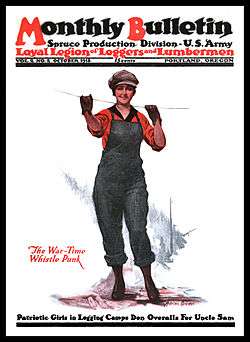

Beginning in March 1918 the Spruce Production Division of the Army and the Loyal Legion published a magazine in Portland, Oregon called the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen Monthly Bulletin. The publication seems to have been terminated early in 1919.

Further reading

- Cloice R. Howd, Industrial Relations in the West Coast Lumber Industry. Miscellaneous Series, Bulletin No. 349. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, 1924.

- Harold M. Hyman, Soldiers and Spruce: Origins of the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen. Los Angeles: Institute of Industrial Relations, University of California., 1963.

- Vernon H. Jensen, Lumber and Labor: Labor in Twentieth Century America. New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1945.

- Edward B. Mittelman, "The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman — An Experiment in Industrial Relations," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 31 (June 1923), pp. 313–341.

- Claude W. Nichols, Jr., Brotherhood in the Woods: The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen: A Twenty Year Attempt at "Industrial Cooperation. PhD dissertation. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon, 1959.

- Cuthbert P. Stearns, History of the Spruce Production Division, United States Army and United States Spruce Production Corporation. Portland, OR: Press of Kilham Stationery & Printing Co., n.d. [c. 1919].

- Charlotte Todes, Labor and Lumber. New York: International Publishers, 1931.

- Rod Crossley, Soldiers in the Woods ISBN 978-0-9831977-1-3 [2014]

- Robert L. Tyler, "The United States Government as Union Organizer: The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen." Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 47 (Dec. 1960), pp. 434–451. JSTOR 1888876

External links

- Brice P. Disque Papers. 1906-1960. 1.89 cubic feet (6 boxes). At the Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

- Erik Mickelson, "The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen: The Origins of the World’s Largest Company Union and How it Conducted Business," Seattle General Strike Project, Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, University of Washington, Seattle, 1999.