Litema

Litema (pronounced: /ditʼɪːma/; also spelled Ditema; Singular: Tema, Sesotho for "field") is a form of Sotho mural art composed of decorative geometric patterns, commonly associated with the South Sotho tradition today practised in Lesotho and neighbouring areas of South Africa. Basotho women generate litema on the outer walls of homesteads by means of engraving, painting, relief mouldings and mosaic. Typically the geometric patterns are scratched with a forefinger or hair comb into the wet top layer of fresh clay and dung plaster, and are then painted with natural dyes or, in contemporary times, manufactured paint. Patterns resemble objects from the natural world and most often mimic ploughed fields or depict plant and animal life, sometimes associated with clan totems. Litema are not a permanent facade design, but decay in the sun or may be washed away by a heavy rain. It is common for women of an entire village to apply litema on special occasions such as a wedding or a religious ceremony.[1]

Etymology

The Sotho noun litema denoting "Sesotho mural art" also refers to the associated concepts of "ploughed lands"[2] and "texts".[3] It is derived from the verb stem -lema (in the infinitive, ho lema "to cultivate"), which is a reflex of the Proto-Bantu root *-dɪ̀m- "to cultivate (esp. with hoe)".[4] The orthographic <l> in li- (Class 10 noun class prefix for Sotho nouns) is pronounced [d] in Sotho since [d] is an allophone of /l/ occurring before the close vowels, /i/ and /u/. The orthographic <e> can have three possible values in Sotho: /ɪ/, /ɛ/, and /e/. In <litema> is pronounced /ɪ/, as per the Proto-Bantu root.

Design

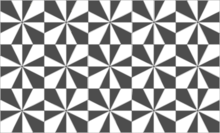

The litema patterns are characterised by a multi-stage symmetry. Patterns are generally arranged in square cells. A wall to be shaped is divided into a grid to form the cells. Each cell is applied with the same pattern, which is usually rotated or mirrored from cell to cell. The symmetry of the overall pattern thus depends on the symmetries present in the basic pattern. There are designs with only one mirror axis in the basic patterns that result in an overall impression of flowing in one direction. Other basic patterns have several axes of symmetry or a rotational symmetry, and give the overall pattern a rather flat ornamental impression. The colour design is restrained, usually only two colours are used[1]

History

The tradition of mural art in Southern Africa is not of recent origins. According to historian Gary van Wyk and researcher, Tom Mathews, excavations at Sotho archaeological sites have revealed archaeological remains in hut floors that have survived the elements for as much as 1500 years. Some of the evidence suggests that mural painting dates back at least five centuries (Grant 1995:45 ; Van Wyk 1998:88). Until the 19th century the geometric patterns were found on the inside rather than the outside of dwellings.[5]

Beginning in the 19th century, the Ndzundza Ndebele mural art tradition called igwalo (more widely known as Ndebele house painting), is said to be a synthesis of a Northern Sotho ditema tradition and the Nguni design traditions employed in beadwork, pottery and basket weaving.[6]

Colonial record

One of the earliest written accounts of Sotho mural art is by the missionary Rev. John Campbell. In his 1813 description of Batlhaping (South Tswana) art, Campbell stated the following:

"Having heard of some paintings in Salakootoo's house, we went after breakfast to view them. We found them very rough representations of the camel-leopard, rhinoceros, elephant, lion, tiger, and stein-buck, which Salakootoo's wife had drawn on the clay wall, with white and black paint. However, they were as well done as we expected, and may lead to something better" (Grant 1995:43).

On his second journey in 1820, Campbell, gave an enthusiastic account of what he saw at the house of a certain chief "Sinosee" of the Hurutse lineage of the Tswana. Campbell provided both illustrations as well as a verbal description of the chief's house. As referred to by Van Wyk and Grant, Campbell's remarks on these ornamented walls were as follows:

"The wall was painted yellow, and ornamented with figures of shields, elephants and camel-leopards, etc. It was also adorned with a neat cornice or border painting of a red colour...its walls (of Sinosee's bedroom) were decorated with delightful representations of elephants and giraffes… In some houses there were figures, pillars, etc moulded in hard clay and painted with different colours that would not have disgraced European workmen. They are indeed an ingenious people" (Grant 1995:43 ; Van Wyk 1998:88).

In the 1880s Campbell's accounts, brought together by historian George Stow, was published in Stowe's 1905 book titled The Native Races of South Africa. This book contains the earliest known drawings of litema – Stow's reproduction of 8 designs made by the "Bakuena" (today better known as the Basotho). Stow's drawings were of textured panels similar to litema engravings. Other illustrations show simple patterns of dots, stripes, triangles and zigzags executed in limited colours (these type of patterns are still seen in Botswana today). Stow's documentation, interestingly enough, did not include any contemporary designs such as those incorporating plant motifs commonly seen in modern-day litema. Van Wyk suggests that the more modern and intricate designs have only developed in more recent history. As referred to by Van Wyk, French missionary Eugene Casallis in 1861 made reference to litema in his book, calling them "ingenious" and far more intricate than those suggested by Stow (Grant 1995:44 ; Van Wyk 1998:89).

Contemporary Revival

Almost a century separates Stow's drawings from those done in 1976 by students of the Lesotho National Teachers Training College. Benedict Lira Mothibe, an art lecturer at the college at the time, instructed students to copy litema designs for the purposes of using these in classroom geometry lessons and as copies for potato prints. More importantly, it was an attempt by Mothibe to revive interest in, what he considered, a worthwhile Sesotho tradition.

More recently (2003), Mothibe, in a further contribution towards the cause of preservation, compiled and donated a second edition on litema designs entitled Basotho Litema Patterns (With Modifications) to the School of Design Technology and Visual Art of the Central University of Technology, Free State.

It is mainly due to the efforts of Benedict Mothibe that we currently have the most updated record of designs and an understanding of the make-up of Litema.[7]

Symbolism

Research conducted by art historians Van Wyk and Mathews in the late-1980s and mid-1990s (culminating in two photographically-illustrated books titled African Painted Houses: Basotho Dwellings of Southern Africa (Van Wyk, 1998) and The African Mural (Chanquion & Matthews, 1989)), concludes that the art of litema cannot be understood in purely aesthetic terms. According to these researchers decorations have symbolic meaning and religious connotations, specifically relating to Basotho life and ancestors.

Van Wyk, in his dissertation titled Patterns of Possession: The Art of Sotho Habitation done for a Ph.D. program in Art History and Archeology at Columbia University, states that Sesotho murals are a form of religious art relating to the beliefs concerning Basotho ancestors, the realm of the Basotho woman, earth, creation, beauty and fertility (both in the fields and in the home). Furthermore, he suggests that the colours of decorations, themselves, have strong symbolic relevance and religious meaning, in some instances even making feminist and political statements. Van Wyk states that, historically, mural decorations brought homage to the ancestors and in more contemporary times, they represent aspects of celebration, ritual and initiation.

Tom Mathews in his writings (supported by photographs of son Paul Chanquion) claims flowers and dots to be symbols of fertility. Furthermore, he states that chevron patterns represent water or uneven ground whilst triangles are symbols denoting male and female. (Changuion & Matthews, 1989:9,19,55).

In the study conducted by the CUT, no persons knowledgeable in the art of litema (Bekker, Thabane and Mothibe) or practising litema artists had any knowledge of a deeper significance other than that of beautifying the home for aesthetic purposes. Some of the artists questioned did however share their opinions concerning the possibility of symbolic meaning. According to artists in the Free State, their mothers (many of whom originate from Lesotho), might have been aware of such meanings, but did not share this information with them during their teaching.[8]

Writing System

One popular commentator has claimed that litema represent an ancient Sotho logographic writing system.[9] As stated above, it is probable that there has always been a symbolic logic associated with litema (perhaps comparable to the tradition of Adinkra symbols in West Africa), but there is little evidence to assert the historical existence of a formal logography of the kind represented in Egyptian hieroglyphics or Chinese characters.

Nevertheless, there is indeed a contemporary writing system (specifically, a featural syllabary) associated with litema, that is used to write Sesotho (and all other Southern Bantu languages). It is called Ditema tsa Dinoko ("Ditema syllabary") and is also known by its Zulu name, Isibheqe Sohlamvu, and various other related names in different languages.[10][11]

Literature

- Paul Changuion: The African mural. New Holland Publishers, London 1989, ISBN 1-85368-062-1.

- Paulus Gerdes: On Mathematical Ideas in Cultural Traditions of Central and Southern Africa. In: Helaine Selin (Hrsg.): Mathematics across cultures: the history of non-western mathematics. Springer, New York 2001, ISBN 1402002602, S. 313–344.

- Paulus Gerdes: Women, Art And Geometry In Southern Africa. Africa World Press, Trenton (NJ) 1998, ISBN 0-86543-601-0.

- Gary van Wyk: African painted houses : Basotho dwellings of Southern Africa. Abrams, New York 1998, ISBN 0-8109-1990-7.

- Sandy and Elinah Grant: Decorated homes in Botswana, Creda Press, Cape Town 1995, ISBN 9991201408.

- Benedict Mothibe: Litema: Designs by Students at the NTTCL, Morija Press, Maseru 1976.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Litema. |

- LITEMA – The mural Art of the Basotho, a Website by Carina Beyer, Photography Programme, School for Design Technology and Visual Art of the Central University of Technology, Free State

References

- 1 2 Paulus Gerdes: On Mathematical Ideas in Cultural Traditions of Central and Southern Africa. In: Helaine Selin (Hrsg.): Mathematics across cultures. New York 2001, S. 329–332.

- ↑ "Bukantswe dictionary search "ploughed land"". bukantswe.sesotho.org. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Bukantswe dictionary search "text"". bukantswe.sesotho.org. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Select Proto-Bantu Vocabulary" (PDF). linguistics.africamuseum.be. 29 May 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Litema, the mural art of the Basotho" (PDF). This Day (South African Newspaper). 27 April 2004. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "The role of decoration in Ndebele society". http://www.sahistory.org.za. 1 January 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Historical Record". http://portal.cut.ac.za/litema. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2015. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Litema Symbolism". http://portal.cut.ac.za/litema. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2015. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Ditema Tsa Basotho Writing System". zulumathabo.wordpress.com. 1 March 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "IsiBheqe". isibheqe.org. 23 August 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Isibheqe Sohlamvu: An Indigenous Writing System for Southern Bantu Languages" (PDF). linguistics.org.za. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.