List of Japanese Nobel laureates

Since 1949, there have been twenty-five Japanese (including Japanese born) winners of the Nobel Prize (Swedish: Nobelpriset). The Nobel Prize is a Sweden-based international monetary prize. The award was established by the 1895 will and estate of Swedish chemist and inventor Alfred Nobel. It was first awarded in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, and Peace in 1901. An associated prize, The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, was instituted by Sweden's central bank in 1968 and first awarded in 1969.

The Nobel Prizes in the above specific sciences disciplines and the Prize in Economics, which is commonly identified with them, are widely regarded as the most prestigious award one can receive in those fields.[1][2] Of Japanese winners, eleven have been physicists, seven chemists, two for literature, four for physiology or medicine and one for efforts towards peace.[2]

In the 21st century, in the field of natural science, the number of Japanese winners of the Nobel Prize has been second behind the U.S.

Laureates

| Year | Laureate | Category | Life | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 |  |

Hideki Yukawa | Physics | 1907–1981 | "for his prediction of the existence of mesons on the basis of theoretical work on nuclear forces".[3] |

| 1965 |  |

Sin-Itiro Tomonaga | Physics | 1906–1979 | "for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics, with deep-ploughing consequences for the physics of elementary particles" – shared with Julian Schwinger and Richard Feynman.[4] |

| 1968 |  |

Yasunari Kawabata | Literature | 1899–1972 | "for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind".[5] |

| 1973 |  |

Leo Esaki | Physics | 1925– | "for their experimental discoveries regarding tunneling phenomena in semiconductors and superconductors, respectively" – shared with Ivar Giaever and Brian David Josephson.[6] |

| 1974 |  |

Eisaku Satō | Peace | 1901–1975 | "Prime Minister of Japan," "for his renunciation of the nuclear option for Japan and his efforts to further regional reconciliation" – Shared with Seán MacBride.[7] |

| 1981 |  |

Kenichi Fukui | Chemistry | 1918–1998 | "for their theories, developed independently, concerning the course of chemical reactions" – shared with Roald Hoffmann.[8] |

| 1987 | .jpg) |

Susumu Tonegawa | Physiology or Medicine | 1939– | "for his discovery of the genetic principle for generation of antibody diversity."[9] |

| 1994 |  |

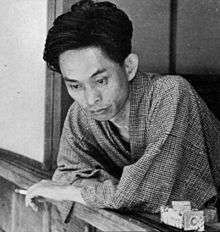

Kenzaburō Ōe | Literature | 1935– | "who with poetic force creates an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today."[10] |

| 2000 |  |

Hideki Shirakawa | Chemistry | 1936– | "for the discovery and development of conductive polymers" – shared with Alan MacDiarmid and Alan Heeger.[11] |

| 2001 |  |

Ryōji Noyori | Chemistry | 1938– | "for their work on chirally catalysed hydrogenation reactions" – shared with William Knowles and Barry Sharpless.[12] |

| 2002 |  |

Masatoshi Koshiba | Physics | 1926– | "for pioneering contributions to astrophysics, in particular for the detection of cosmic neutrinos" – shared with Raymond Davis, Jr. and Riccardo Giacconi.[13] |

|

Koichi Tanaka | Chemistry | 1959– | "for the development of methods for identification and structure analyses of biological macromolecules" and "for their development of soft desorption ionisation methods for mass spectrometric analyses of biological macromolecules" – shared with John Fenn and Kurt Wüthrich.[14] | |

| 2008 |  |

Yoichiro Nambu (USA citizen) |

Physics | 1921–2015 | "for the discovery of the mechanism of spontaneous broken symmetry in subatomic physics" – held American nationality – shared with Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa.[15] |

|

Makoto Kobayashi | Physics | 1944– | "for the discovery of the origin of the broken symmetry which predicts the existence of at least three families of quarks in nature" – shared with Yoichiro Nambu and Toshihide Maskawa.[15] | |

|

Toshihide Maskawa | Physics | 1940– | "for the discovery of the origin of the broken symmetry which predicts the existence of at least three families of quarks in nature" – shared with Yoichiro Nambu and Makoto Kobayashi.[15] | |

|

Osamu Shimomura | Chemistry | 1928– | "for the discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein, GFP" – shared with Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien.[16] | |

| 2010 |  |

Ei-ichi Negishi | Chemistry | 1935– | "for palladium-catalyzed cross couplings in organic synthesis" – shared with Richard F. Heck and Akira Suzuki.[17] |

|

Akira Suzuki | Chemistry | 1930– | "for palladium-catalyzed cross couplings in organic synthesis" – shared with Richard F. Heck and Ei-ichi Negishi.[17] | |

| 2012 |  |

Shinya Yamanaka | Physiology or Medicine | 1962– | "for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent" – shared with John B. Gurdon.[18] |

| 2014 |  |

Isamu Akasaki | Physics | 1929– | "for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources" – shared with Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura.[19] |

|

Hiroshi Amano | Physics | 1960– | "for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources" – shared with Isamu Akasaki and Shuji Nakamura.[19] | |

|

Shuji Nakamura (USA citizen) |

Physics | 1954– | "for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources" – shared with Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano.[19] | |

| 2015 |  |

Satoshi Ōmura | Physiology or Medicine | 1935– | "for their discoveries concerning a novel therapy against infections caused by roundworm parasites" – shared with William C. Campbell and Tu Youyou.[20] |

|

Takaaki Kajita | Physics | 1959– | "for the discovery of neutrino oscillations, which shows that neutrinos have mass" – shared with Arthur B. McDonald.[21] | |

| 2016 | Yoshinori Ohsumi | Physiology or Medicine | 1945- | "for his discoveries of mechanisms for autophagy"[22] | |

Laureates with Japanese linkage

| Year | Laureate | Category | Life | Rationale | Linkage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 |  |

Yuan T. Lee | Chemistry | 1936– | "for their contributions concerning the dynamics of chemical elementary processes" – shared with Dudley R. Herschbach and John C. Polanyi.[23] | Lee is a Taiwanese scientist of ancient Han Chinese descent and was born in Taiwan, which was then under World War II Japanese rule, he can speak fluently in Japanese, English, Taiwanese and Mandarin Chinese. He was graduated from the National Taiwan University - one of former Japanese Imperial universities. In addition, Lee is also the Honorary Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of Nagoya University in Japan. |

| 1987 | Charles J. Pedersen | Chemistry | 1904–1989 | "for their development and use of molecules with structure-specific interactions of high selectivity" – shared with Donald J. Cram and Jean-Marie Lehn.[24] | Pedersen has a Japanese mother, his Japanese first name was Yoshio (良男). | |

In 1960s, Anthony James Leggett spent a year in the group of Professor Takeo Matsubara at Kyoto University in Japan, he can speak fluently in Japanese and English. His wife is a Japanese researcher Haruko Kinase.

Nominations

- Physics

- Shoichi Sakata reported the "Sakata model" - a model of hadrons in 1956, that inspired Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig's quark model. Moreover, Kazuhiko Nishijima and Tadao Nakano originally given the Gell-Mann–Nishijima formula in 1953.[25] However, 1969 physics prize was only awarded to Murray Gell-Mann. Afterward, Ivar Waller, the member of Nobel Committee for Physics was sorry that Sakata had not received a prize.[26]

- Yoji Totsuka was leading the experiment that the first definitive evidence for neutrino oscillations was measured, via a high-statistics, high-precision measurement of the atmospheric neutrino flux. His Super-K group also confirmed, along with the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO), the solution to the solar neutrino problem. The Nobel Prize winning physicist Masatoshi Koshiba was told that if Totsuka could extend his lifespan by eighteen months, he would receive the physics prize.[27]

- Chemistry

- Eiji Osawa prediction of the C60 molecule at Hokkaido University in 1970.[28][29] He noticed that the structure of a corannulene molecule was a subset of an Association football shape, and he hypothesised that a full ball shape could also exist. Japanese scientific journals reported his idea, but it did not reach Europe or the Americas.[30][31] Because of this, he was not awarded the 1996 chemistry prize.

- Physiology or Medicine

- Kitasato Shibasaburō and Emil von Behring working together in Berlin in 1890 announce the discovery of diphtheria antitoxin serum, Von Behring was awarded the 1901 prize because of this work, but Kitasato was not. Meanwhile, Hideyo Noguchi[32] and Sahachiro Hata,[33] those who missed out on the early Nobel Prize for many times.

- Katsusaburō Yamagiwa and his student Kōichi Ichikawa successfully induced squamous cell carcinoma by painting crude coal tar on the inner surface of rabbits' ears. Yamagiwa's work has become the primary basis for research of cause of cancer.[34] However, Johannes Fibiger was awarded the 1926 prize because of his incorrect Spiroptera carcinoma theory, while the Yamagiwa group was snubbed by Nobel Committee. In 1966, the former committee member Folke Henschen claimed "I was strongly advocate Dr. Yamagiwa deserve the Nobel Prize, but unfortunate it did not realize".[35] In 2010, the Encyclopædia Britannica 's guide to Nobel Prizes in cancer research mentions Yamagiwa's work as a milestone without mentioning Fibiger.[36]

- Umetaro Suzuki completed the first vitamin complex was isolated in 1910.[37] When the article was translated into German, the translation failed to state that it was a newly discovered nutrient, a claim made in the original Japanese article, and hence his discovery failed to gain publicity. Because of this, he was not awarded the 1929 prize.

- Satoshi Mizutani[38] and Howard Martin Temin jointly discovered that the Rous sarcoma virus particle contained the enzyme reverse transcriptase, and Mizutani was solely responsible for the original conception and design of the novel experiment that confirmed Temin's provirus hypothesis.[39] However, Mizutani was not awarded the 1975 prize along with Temin.

- As of 2015, there have been seven Japanese who have received the Lasker Award and twelve Japanese who have received the Canada Gairdner International Award, but only three Japanese who have received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

- Others

- A number of important Japanese native scientists were not nominated for early Nobel Prizes, such as Yasuhiko Kojima and Yasuichi Nagano (jointly discovered Interferon), Jokichi Takamine (first isolated epinephrine),[40] Kiyoshi Shiga (discovered Shigella dysenteriae), Tomisaku Kawasaki (Kawasaki disease is named after him), and Hakaru Hashimoto. After World War II, Reiji Okazaki and his wife Tsuneko were known for describing the role of Okazaki fragments, but he died of leukemia (sequelae of Atomic bombings of Hiroshima) in 1975 at the age of 44.

See also

- List of Japanese people

- List of Nobel Laureates

- List of Nobel Laureates by country

- List of Asian Nobel laureates

- List of Nobel laureates affiliated with Kyoto University

References

- ↑ "Nobel Prize". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- 1 2 "All Nobel Laureates". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1949". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1965". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1968". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1973". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1974". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1981". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1987". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1994". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2000". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2001". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2002". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2002". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2008". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- 1 2 "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2010". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2012". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2014". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2013" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2015". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2016". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1986". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1987". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ Nakano, T; Nishijima, N (1953). "Charge Independence for V-particles". Progress of Theoretical Physics. 10 (5): 581. Bibcode:1953PThPh..10..581N. doi:10.1143/PTP.10.581.

- ↑ Robert Marc Friedman, The Politics of Excellence: Behind the Nobel Prize in Science. New York: Henry Holt & Company (October 2001)

- ↑ 文藝春秋2008年9月号.

- ↑ Osawa, E. (1970). "Superaromaticity". Kagaku. 25: 854–863.

- ↑ Halford, B. (9 October 2006). "The World According to Rick". Chemical & Engineering News. 84 (41): 13. doi:10.1021/cen-v084n041.p013.

- ↑ Kagaku 25: 854–863. 1970.

- ↑ Yoshida, Z.; Osawa, E. (1971). Aromaticity. Chemical Monograph Series 22. Kyoto: Kagaku-dojin. pp. 174–8.

- ↑ Japanese Government Internet TV "Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize," streaming video 2007/04/26

- ↑ Sachachiro Hata - Nomination Database

- ↑ "Katsusaburo Yamagiwa (1863–1930)". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 27 (3): 172. 1977. doi:10.3322/canjclin.27.3.172.

Yamagiwa, then Director of the Department of Pathology at Tokyo Imperial University Medical School, had theorized that repetition or continuation of chronic irritation caused precancerous alterations in previously normal epithelium. If the irritant continued its action, carcinoma could result. These data, publicly presented at a special meeting of the Tokyo Medical Society and reprinted below, focused attention on chemical carcinogenesis. Further more, his experimental method provided researchers with a means of producing cancer in the laboratory and anticipated investigation of specific carcinogenic agents and the precise way in which they acted. Within a decade, Keller and associates extracted a highly potent carcinogenic hydrocarbon from coal tar. Dr. Yamagiwa had begun a new era in cancer research.

- ↑ 「『ガンの山極博士』たたえる」読売新聞1966年10月25日15頁。

- ↑ Guide to Nobel Prize. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Suzuki, U., Shimamura, T. (1911). "Active constituent of rice grits preventing bird polyneuritis". Tokyo Kagaku Kaishi 32: 4–7; 144–146; 335–358.

- ↑ H. M. Temin and S. Mizutani (1970). "Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus" (PDF). Nature. 226 (5252): 1211–3. Bibcode:1970Natur.226.1211T. doi:10.1038/2261211a0. PMID 4316301.

- ↑ Horace Freeland Judson, The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science, 1st. Ed., 2004.

- ↑ Wermuth, Camille Georges (2008). The practice of medicinal chemistry (3 ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780080568775.

External links

- All Nobel Laureates from the Nobel Foundation

- Japanese Nobel Laureates — Kyoto University(English)

- 日本人のノーベル賞受賞者一覧 — 京都大学(Japanese)

- Nominees from JAPAN - Nomination Database(English)