LSWR suburban lines

This article deals with the development of the London suburban railway lines of the London and South Western Railway (LSWR). For the wider view of the LSWR in general, see London and South Western Railway.

The London and Southampton Railway opened its main line progressively from 1838 and a year later changed its name to the London and South Western Railway. It was immediately successful, especially for passenger traffic, and the company quickly extended south-west and west to Gosport, Dorchester and Salisbury. At the same time it energetically and prospectively developed or acquired branch or loop lines in the territory to Windsor, Wokingham, Epsom and Guildford and beyond.

The "suburban area" is taken in this article to include the LSWR lines in what is now Greater London, Surrey and small parts of Berkshire extending to Twickenham, Ascot and Windsor in the north, and Epsom and Leatherhead in the south, as well as suburban development on the main line as far as Weybridge and the Chertsey loop. When the lines were promoted, places served on these lines were recorded such as in the Victoria County History of Surrey in 1910-1912 as rural villages, London suburbs or towns.

The first main line

The London and Southampton Railway opened its main line between the two named places progressively from 1838, completing the route on 11 May 1840. The London terminal was at Nine Elms. Passenger traffic was extremely buoyant, and racegoers overwhelmed the capacity of the Company's trains in the second week of operation. The Company had been frustrated over early intentions to reach Bristol, and harboured the objective of securing territory west of Southampton, but it did not neglect the potential of local traffic closer to London, and early timetables show two types of passenger train service: throughout from London to Southampton, in many cases omitting station calls nearer to London, but also local trains from London to Weybridge.[1]

The London terminal at Nine Elms on the River Thames afforded onward travel to central London by river steamer and taxi carriage. The location was never intended as a permanent London passenger terminal; an extension eastwards was contemplated in 1836, and was decided upon in 1844. Nonetheless contemporaries note that with few rival railways in its sector "The London passenger found it more convenient than other companies' stations. He might leave it by road and frequently dip his hand for Turnpike tolls, or for 3d choose the steamer Citizen, or the opposing Bridegroom, to reach the capital by river, cursing his choice when the rival vessel arrived and cleared the other queue while his own waited half an hour."[2]

The stations as far as Weybridge were

- Nine Elms;

- Wandsworth, about half a mile (nearly 1 km) south-west of the present Clapham Junction station, fronting onto Battersea Rise;

- Wimbledon; somewhat to the west of Wimbledon Hill Road and of the present station;

- Kingston; on the east side of King Charles Road, about half a mile (nearly 1 km) east of the present Surbiton station;[note 1]

- Ditton Marsh; renamed Esher & Hampton Court in 1840; now Esher;

- Walton; renamed Walton and Hersham in 1849; now Walton-on-Thames;

- Weybridge

The London and Southampton Railway changed its name to the London and South Western Railway on 4 June 1839.[3]

Kingston-upon-Railway

The town of Kingston upon Thames was steadily growing and very commercial before the arrival of the railway.[4] Once the main line was built, at closest, 1.1 miles (1.8 km) south of the town, a station was provided in the deep cutting there called 'Kingston' in one of its several former tythings.

The existence of the station, and the convenience of travelling to London from it, prompted many streets to be laid out close to the station, and for a time the settlement may have been known as Kingston-upon-Railway. The 1841 Year Book of Facts says

Railway town—Upon the South-western line a new town, called Kingston-upon-Railway, is fast rising, 800 houses being built or in progress.[5]

The station name later changed from Kingston to Surbiton, and later Ordnance Survey maps name the station after its new-founded parish and former hamlet as Surbiton.[6] The Year-Book may have been poetic or short-lived house builders' patter however writers such as and Hamilton-Ellis (1962) and Gillham (2007) imply it was at some point the station name.[7][8]

Early extensions, to 1850

Richmond

Early in the life of the new railway, Richmond was the heart of a lucrative residential area for developers generating significant travel to and from London: 98 omnibuses made the journey each way daily in 1844. Local promoters developed a scheme for a railway from Richmond to join the LSWR at Wandsworth and to extend the LSWR line north-eastward from near Nine Elms to Hungerford and Waterloo Bridges. Responsibility for the eastward extension passed to the LSWR, but the Richmond Railway Act received the Royal Assent on 21 July 1845. Three LSWR directors were on the board of the new company raising its nominal capital of £260,000 (equivalent to £23,000,000 in 2015).[9]

A few road bridges were built, the 1,000 feet (305 m) viaduct/bridge at Wandsworth over the Wandle (and the Surrey Iron Railway) and a deep cutting through about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) of Putney but via a flattish route, rural at the time, minimal other bridges, embankments or cuttings. Construction was swift and the line opened on 27 July 1846.[10]

This line runs due east: through Mortlake, Barnes, Putney and Wandsworth with stations for those parishes, the last close to the present Wandsworth Town station — about a mile from the LSWR Wandsworth station just within the Battersea boundaries, which was renamed Clapham Common at the same time. The line joined at Falcon Bridge, by today's Falcon Road, and ran alongside it, forming four tracks to Nine Elms.[11] The Richmond terminus was slightly south, by Drummond Place.[12]

In early years 17 trains each way between Richmond and Nine Elms.[2] The Richmond company sought to sell their line to LSWR and after some prevarication a merger was agreed, with a share exchange valuing Richmond shares at a premium, and with a Richmond director appointed to the LSWR board when a vacancy arose. The merger took effect on 31 December 1846.[2]

Waterloo

The Nine Elms station was never intended to be a permanent London terminal so in 1845 the LSWR obtained powers to extend to a more central site, Waterloo Bridge by that road bridge (changed to today's Waterloo in 1886). A second Act in 1847 authorised the extending of two further tracks, reflecting the separate Richmond Railway's completion in 1846.

Running through residential Battersea and Lambeth ancient parishes, the construction displaced about 700 houses. Starting from an embankment near Nine Elms, this line was to assist with gradients and built on viaduct as was Waterloo station itself. The line, terminus and Vauxhall new stations opened on 11 July 1848. Waterloo Bridge station occupied ten acres, with six tracks serving four platforms[note 2] The terminus was a cheap, temporary structure.[13][14]

Waterloo was aligned to enable eastward extension and on 26 August 1846 the LSWR obtained an Act permitting an extension to Borough High Street to face the London Bridge station of the South Eastern Railway (SER). This would have given public access to the City of London without building a railway bridge over the Thames. Some land was bought but in the slump following the railway mania the Company reflected on the huge cost of constructing an inner-urban line, and allowed the powers to lapse.[13]

On to Windsor, and a Hounslow loop

This period in 1846 was the time of the railway mania, when all manner of railway schemes were being promoted with the promise, often unfulfilled, of making subscribers rich. The LSWR was not to be left behind, and now was pressing the Richmond line westwards, but was beset with multiple independent schemes competing for the same territory. These included, an 1846 'Windsor, Slough and Staines Atmospheric Railway' company which would probably have used broad gauge. However it was induced by the 'Richmond and Staines Junction Railway' company to form a joint venture, the Windsor, Staines and South Western Railway company (WS&SWR), rebuffing the overtures of an atmospheric railway. The new company was friendly to the LSWR and had Joseph Locke as its engineer.

The Company obtained a No. 1 Act on 25 June 1847. With capital of £500,000 it built the line from a junction with the Richmond railway slightly east of Richmond station, passing to the north of the original terminus and crossing the Thames, and running through Twickenham and Staines to a terminus at uninhabited 'Black Potts' on the Thames 1,100 yards (1 km) north-west of Datchet, a bridge to Windsor on the opposite bank, not yet authorised. However it did authorise the Company to conclude an agreement with the Commissioners of Woods and Forests to pay £60,000 for improvements to Windsor Great Park; a thinly disguised enabling payment to build on through the Home Park to Windsor's historic centre.

The No. 1 Act also authorised the new line from Barnes, crossing the Thames and running through Brentford and Isleworth to Hounslow, and rejoining the above line.

The Great Western Railway (GWR) sought its own Windsor railway, for the great prestige of serving Queen Victoria, and had secured approval from the Commissioners over their proposed approach. For a time it appeared that the GWR would succeed and the WS&SWR company, having paid the £60,000, would be refused. However at last both companies obtained approval to come to Windsor — on 26 June 1849 the second Act benefitting the WS&SWR permitted the Windsor and Eton Riverside station, not quite so convenient for Windsor as preferred. Very convenient to Eton, stringent conditions were imposed to prevent scholars at Eton College from immoral or unlawful use.

Railway mania ended leaving few speculative investors, but the line from Richmond to Datchet was opened to the public on 22 August 1848. The extension to Windsor was delayed when the piers of the Thames bridge at Black Potts settled, and the line was opened belatedly on 1 December 1849,[10] 8 weeks after the GWR had reached its own Windsor station. Even then it was to a cramped temporary station; opening of the lavish permanent station, with Royal waiting room and cavalry entrance, was seventeen months later, on 1 May 1851.[2]

Meanwhile, the Hounslow loop had been progressing more slowly, reaching (Smallberry Green), Isleworth east of its successor by 22 August 1849 and completed to the junction on the heath in Feltham parish on 1 February 1850.[10]

The WS&SWR merged by share transfer with the LSWR on 30 June 1850.[2]

Chertsey and Hampton Court

The LSWR obtained an Act on 16 July 1846 authorising a line from Weybridge via Chertsey to a terminus near Staines bridge, on the south side at Egham. However the WS&SWR No 2 Act (the No 1 Act was described under Windsor, above) foreshortened this Chertsey, Parliament preferring to let the WS&SWR have scope take territory between Staines and Pirbright with a southerly Chertsey line proposal of its own. The slump following the railway mania killed off this WS&SWR scheme, but by then the LSWR was opening from Weybridge to Chertsey, on 14 February 1848.[2]

Hampton Court Palace attracted already 178,000 visitors annually, and a branch was proposed, and opened on 1 February 1849.[2][10] Cobb states that the intermediate station at Thames Ditton was opened in 1851, but Butt says that it opened with the opening of the branch.[15][16] The branch was worked by horse traction at first, a vehicle being detached from main line trains at the junction. By 1855 trains from London travelled conventionally.[17]

Waterloo and eastwards aspirations

Having reached Waterloo, the LSWR still harboured a desire to get nearer to the City of London, which was the chief destination of arriving passengers. Improvised Waterloo was added to incrementally in 1854, 1860, 1869, 1875, 1878 and 1885 with no coherent plan.

It was the South Eastern Railway who made the first move in 1859, promoting and largely funding a London Bridge and Charing Cross Railway (CCR) company, which obtained an Act. It was to have three tracks; it did not envisage today's Waterloo East, but there was to be a 5 chains (330 ft; 100 m) connection to the LSWR Waterloo Bridge station. It was authorised as double track, but was actually built as single. The cost of all alterations at the LSWR station was to be borne by the CCR. The CCR line was opened to traffic on 11 January 1864, but the branch into the LSWR station was "opened" but no trains ran.

The LSWR had opposed the CCR scheme in Parliament (asking unsuccessfully the SER to allow use of or track to London Bridge station) — SER would soon have its Charing Cross (City of Westminster) second 'London' terminus. The CCR said that they had fulfilled their obligations under the Act by building the connecting line.

After much argument, the SER arranged a London Bridge service jointly with the London and North Western Railway (LNWR); it ran from Euston via Willesden and Kensington, to be owned by the LSWR from Kensington via Waterloo; this started running on 1 July 1865. Although London Bridge station was near to the City of London, it was on the south of the river, and by now Cannon Street station on the north bank in the heart of the financial district. The station was about to be opened: the LSWR asked for the trains to be allowed to run to that station. The SER replied requiring either very high charges for the facility, or alternatively running powers to any point on the LSWR within 26 miles (42 km) of London.

This would be too costly and further difficult negotiations took place, during which the Euston - Waterloo - London Bridge service was discontinued, apparently late in 1866. On 1 February 1867 a new service started from Willesden via Kensington and Waterloo to Cannon Street. Engine and crew changes took place at Kensington (from LNWR to LSWR) and Waterloo (LSWR to SER). Late in 1867 the SER again gave notice to discontinue the service and the last service train ran over the Waterloo connection on 31 December 1867. A few van shunts, and also the Royal Train, were the only movements over the line after that. The next month the SER was negotiating an amalgamation with the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR) and the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&DR). The LSWR was invited to join too and did more than refuse. The LSWR successfully opposed the Bill of the three companies. The SER now agreed to build a Waterloo calling point on the Charing Cross line if the LSWR would withdraw its opposition.

This was agreed, and "Waterloo Junction" station opened on 1 January 1869; the amalgamation plans of the other railways foundered meanwhile. Waterloo Junction was renamed Waterloo on 7 July 1935 and Waterloo East arose on 2 May 1977.[13][14]

More branches, 1851 to 1862

North and South Western Junction

The proximity of the unconnected railways immediately west of London led to a number of failed schemes, until in 1851 the North and South Western Junction Railway (N&SWJR) built a line just under 4 miles long from an east-facing junction at Willesden to Kew Junction (later by Kew Bridge station), facing west in the east side of Brentford.[2][9]

The line was to be worked by the LSWR and the London & North Western Railway (LNWR) jointly, but at first the larger companies delayed providing the trains service. Eventually a goods service was started on 15 February 1853, followed by passenger traffic on 1 August 1853: four North London Railway trains daily ran from Hampstead Road (connection from Fenchurch Street) to Kew; the N&SWJR had its own Kew station just short of the LSWR line—a temporary platform at first.[2][14][18]

Overcoming the reluctance of the LSWR, the N&SWJR started to run through to Windsor, with three additional trains from Hampstead Road to Windsor from 1 June 1854, a service which ended that October.

Curves at Brentford and Barnes

Responding to pressure for alternative London services to Richmond and its Windsor via Staines and Twickenham line, the LSWR arranged with the N&SWJR to run a Twickenham - Richmond - Hampstead Road service, reversing at Barnes and again at Brentford ('Kew Junction'); some LSWR coaches continued to Fenchurch Street, London. The service started on 20 May 1858. The two reversals were obviously extremely inconvenient, and the LSWR, warming to the N&SWJR, obtained powers to build an east curve at the part of Brentford freely named Kew Junction and a west curve at Barnes; they opened on 1 February 1862. Williams points out that the passenger timings hardly improved, the Kew Junction to Richmond times reducing from 19 minutes to 16 minutes. The junction was closest to the LSWR station and it built platforms on the north-east curve for the new northbound train service. The original north-west and east-west Kew Junction was renamed Old Kew Junction.[2][18][note 3]

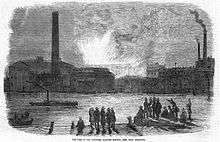

Vauxhall station fire

Vauxhall station suffered an immense fire on Sunday 13 April 1856; the fire was observed at 8.15 p.m. to be burning a canvas and paper wall in a passage leading to some offices. A train actually passed through the conflagration and another stopped at the station to set down passengers, before the local traffic manager was able to take charge and divert up trains to the old Nine Elms station. The entire timber station building burnt down. Nonetheless the permanent way was not much damaged and trains ran as usual the following day.[19]

Epsom and Leatherhead

In the early years of the 1840s the thoughts of the Company turned to the area towards Epsom and beyond. However both the London and Brighton Railway and the London and Croydon Railway considered the area attractive to them, which might enable a line to Portsmouth. A series of bilateral agreements were concluded undertaking not to encroach on other lines' presumed areas of influence.[note 4]

At this period Parliament commissioned an external panel of experts, the so-called Railway Kings, to adjudicate preference between competing schemes and to asess practicability and desirability, and this led to the suppression in 1844 of a LSWR proposal to reach Epsom; a further Bill was rejected in 1846. However, in that year the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) was formed by the amalgamation of the Croydon and Brighton companies, and in 1847 the LBS&CR opened the line from its (West) Croydon station to Epsom. The LSWR turned its focus more towards Portsmouth, Guildford and Chichester, which also proved contentious.[20]

In 1855-1856 two semi-independent companies were promoted, the Epsom and Leatherhead Railway (E&LR) and the Wimbledon and Dorking Railway (W&DR). They obtained Parliamentary authorisation, the E&LR on 14 July 1856, to run from the LB&SCR station at Epsom to Leatherhead. The W&DR obtained authority on 27 July 1856 for a line from near Wimbledon to join the E&LR a little to the west of the LB&SCR Epsom station, and also to build from Leatherhead to Dorking.

The W&DR was dependent on the LSWR, but the E&LR was independent, and looking for a larger company to work it, it found the LSWR unwilling, because of its territorial agreement with the LB&SCR. The E&LR directors now approached the LB&SCR who agreed to work the line, in contravention of the same agreement. However E&LR shareholder dissatisfaction was evident, not least because the LB&SCR route to London (London Bridge station via Croydon) was much longer than the route to Waterloo. An Extraordinary General Meeting was called, and the Board was instructed to negotiate further with the LSWR, and this resulted in the LSWR winning control of the E&LR. They leased and opened the single track line on 1 February 1859 between Epsom (LB&SCR station) and Leatherhead. The LSWR provided seven trains daily, connecting with the LBSCR trains at Epsom.

Soon the LSWR was able to open the leased W&DR line between Wimbledon and the junction near Epsom, on 4 April 1859, enabling their trains to run to Leatherhead. Wimbledon station was then south-west of Wimbledon Bridge, and the new line ran parallel to the main line from there as far as the present-day Raynes Park station. At first there was no Epsom station on the route, but four days later Parliament authorised the construction of a new station at the junction. It was built so that trains from the LB&SCR station passed through, platforms only being provided for trains from the Wimbledon line.

On 29 July 1859 the LB&SCR and the LSWR agreed to make the E&LR joint between them, and to double it when required, and from 8 August 1859 LB&SCR trains started running over the E&LR. The joint ownership of the E&LR was authorised by Parliament, and was approved by shareholders on 30 September 1861.[20]

When Epsom junction was enlarged and the line doubled, the two centre tracks led served the onward LB&SCR station, and platforms were restricted here to LSWR trains. This arrangement lasted until 1929.[21]

Wokingham

After proposals to extend westward from Staines failed in Parliament the depression following the Railway Mania seemed ever deeper and the LSWR did not progress the schemes further. Local interests were reluctant to see their railway ignored thus the Staines, Wokingham and Woking Junction (informally 'and Reading') Railway company was formed[note 5] on 8 July 1853 to make a line from Staines (LSWR) to a junction with the South Eastern Railway's Redhill, Guildford and Reading line at Wokingham. Running powers over the SER line were obtained, and narrow gauge track into Reading station on the Great Western Railway gave the SW&WJR trains access to Reading.

Included were unexercised powers to make a branch to Woking via Chobham.[22]

The line opened from Staines to Ascot on 4 June 1856 and from there to Wokingham on 9 July. The Wokingham line was worked by the LSWR and later absorbed by it.[9][15][20][23]

Wraysbury station moved

Wraysbury station was moved about a quarter mile towards Staines on 1 April 1861.[15][16] The old site was served only by a footpath; perhaps due to objection by the occupier of Wyrardisbury House. The new station is also often referred to as Wyrardisbury on the Ordnance Survey maps of the period.[6]

From 1862 to 1869

Eastward to the City of London

After the extension to Waterloo Bridge in 1848, the Company had a terminal reasonably close to the commercial areas of London. Yet as business travel increased over the years, its inconvenience to parts of the City of London became increasingly objectionable. However early efforts to get access to Cannon Street had seen short-lived success, where the South Eastern Railway defended its investment.

The LSWR had more success with the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&DR). By Acts of 1860 and 1861 the LC&DR was authorised to build a line from Herne Hill quite near Clapham to Ludgate Hill in the City, crossing the Thames at Blackfriars, and the short way to the LB&SCR and the West London Extension Railway and the LSWR. Further Acts in 1864 and 1866 ratified changes of plan, but the friendly relations culminated in an Agreement between the LSWR and the LC&DR dated 5 January 1865.[note 6] An arrangement for sharing ticket income was reached.

The LC&DR had already opened its line from Victoria to Bromley, but it now opened its Ludgate Hill line striking north from Loughborough Junction, and a link to the LSWR at Clapham Junction. From 3 April 1866 LSWR trains ran from Kingston, Richmond and Hounslow, via Clapham Junction, Wandsworth Road and Loughborough Road to Ludgate Hill.[24][25]

Kensington and Richmond

In the 1860s, numerous new schemes were promoted for railways to reach Richmond, causing LSWR alarm for its primacy in Richmond and both it and the N&SWJR alarm for their '(north) Kew' Brentford station. After much wrangling, the LSWR obtained an Act on 14 July 1864 for a line from the north end of Kensington through Hammersmith to Richmond. The West London Extension Railway had opened in 1863, connecting to the LSWR at Clapham Junction. The LSWR had subscribed one-sixth of the capital cost of the new line, which was operated as a joint line. In 1863 the east facing spur to West London Junction opened,[18] giving direct access from Waterloo to Kensington. Kensington station had been slightly relocated, considerably expanded, and renamed Kensington (Addison Road).[14] As a minority partner in the WLER, the LSWR's right to run north of Kensington, even for a few hundred yards, was contentious. This Bill had been hastily prepared and further Acts were obtained in 1865, 1866 and 1867 making a number of improvements.

The LSWR's new route opened on 1 January 1869; it was from Richmond Junction north of Kensington, turning south through its own Shepherds Bush and Hammersmith (Grove Road) stations, and it then turned west along the alignment that is now the District line from Ravenscourt Park to Turnham Green, then turning south-west through Brentford Road station (now called Gunnersbury), crossing the Thames to Richmond. A short spur was also opened from Acton Jn (later South Acton Jn) on the North and South Western Junction Railway to a junction at Brentford Road, giving the NLR direct access to Richmond. The main line ran to a terminus at Richmond, adjacent to the LSWR through station; this prevented the North London Railway (NLR) from petitioning for running powers to continue westward over the Staines lines, to Windsor, Reading or Woking.

The LSWR allocated six of Beattie's 2-4-0WT locomotives to the new service.[26]

This access removed the requirement to accept trains from the N&SWJR via the north-facing 'Kew' and south-facing Barnes curves, the former being mothballed and the latter later removed. A new spur was opened from south of Brentford Road (Gunnersbury) to the Hounslow Loop, referred to as The Chiswick Curve and also a connection was made at Hammersmith with the Hammersmith & City Railway; these probably opened on 1 June 1870.

The LSWR now ran trains from Waterloo to Richmond via Kensington (Addison Road) and Hammersmith, and also from Ludgate Hill to Richmond.[24]

All of this activity was a strategy to minimise other railways' access to all points south and west of Richmond and if possible that town. The last bid failed: as well as the North London trains from Broad Street in the City of London, Richmond gained (from 1 June 1870) GWR trains arriving from Bishops Bridge Road via the Hammersmith & City Railway. In 1875 the Metropolitan District Railway made a short connection westward from its Hammersmith station to the LSWR at Studland Road Junction in that town enabling its trains to reach Richmond, from 1 June 1877. This straight combination forms today's District line.

In 1868 the Midland Railway had made a connection between Cricklewood and the N&SWJR, and it had been contemplating a purchase of the N&SWJR. To deflect from southward ambitions, the LSWR built a north-to-east curve (the Acton Curve) from Bollo Lane Junction to Acton Lane Junction, giving access to trains approaching from Willesden or Cricklewood eastwards to Hammersmith and Kensington. Midland coal trains started using this to Kensington (High Street) from 4 March 1878, and also for a time ran passenger trains to Richmond from Moorgate Street via Cricklewood.

Kingston

The town of Kingston had had its somewhat remote station on the main line from the outset and the LSWR obtained powers to reach the town centre, from the north-west. The line was authorised on 6 August 1860, a single arc from Twickenham, approaching Kingston from the west. There was pressure to terminate the line on the west side of the River Thames, at Hampton Wick. This would have required passengers arriving to pay the halfpenny toll to cross the river bridge on foot to Kingston.[17] The LSWR did not wish to open a Hampton Wick station. However the Lords Committee had inserted a clause requiring them to make and maintain a Hampton Wick station as well. The line opened on 1 July 1863, with stations at Teddington, Hampton Wick and New Kingston. As well as LSWR trains, the North London Railway operated passenger trains to Kingston under a duty on LSWR in an earlier Act.[27]

Tooting and Ludgate Hill

In 1855 the Wimbledon and Croydon Railway had opened between those places[note 7] via Mitcham,[9] and the railway was absorbed by the LB&SCR in 1858. At Wimbledon the line curved in from the south-east and ran to a separate station north-east of Wimbledon Bridge. The LSWR passenger station was south-west of the bridge, and the W&C line had a separate spur connecting to the LSWR south-west of the station.

In 1864 the Tooting, Merton and Wimbledon (TMW) Railway got its Act for a line from Streatham Junction to Wimbledon, including two routes from Tooting to Wimbledon forming a loop, combined with the Wimbledon and Croydon Railway north-west of Merton.[note 8][24][28][9]

By the TMW Extension Railway Act of 5 July 1865, the powers of the original company were taken over by the LSWR and LB&SCR jointly. The LB&SCR granted running powers to the LSWR to London and also Crystal Palace, and over the Merton to Wimbledon section of the W&C line. They also agreed running arrangements for goods traffic to Deptford Wharf. At this time the LC&DR opened a spur from Herne Hill to Knights Hill (later Tulse Hill); oddly, they seem to have been alarmed that the LB&SCR granted the running powers to the LSWR to pass through Knights Hill.[29]

The TMW lines opened to LB&SCR trains in October 1868 and to LSWR trains on 1 January 1869. The LSWR could now run to Ludgate Hill from Wimbledon via Tooting, Streatham and Herne Hill.[24]

On the line from Streatham Junction, the stations were Tooting Junction, in the nook of the junction, followed by Haydons Lane (renamed Haydons Road on 1 October 1889).[16] [note 9][30]

The TMW station at Wimbledon was north-east of Wimbledon Bridge, while the LSWR main line station was south-west of it. The earlier spur from the W&C line to the LSWR was now unnecessary (as the TMW made its own connections) and was abandoned.

On the southern arm of the route from Tooting Junction to Wimbledon, the intermediate Morden station was 'Merton Abbey', followed by a station Lower Merton at the point of convergence with the Wimbledon and Croydon line. At first the platforms were only on the Tooting line. The TMW line was double track, but the W&C line was single at the time, being doubled between Lower Merton and Wimbledon in 1868. A platform on the Croydon line was provided from 1 November 1870, and the station name was changed to Merton Park on 1 September 1887.[30]

Shepperton

In 1861 promoters raised funds for connecting the Thames Valley towns and villages perhaps from Isleworth and certainly through Richmond, Hampton and Shepperton, ideally being a south-west link from the GWR to the Southampton line. City access would be via the Metropolitan Railway at Richmond. They formed the Metropolitan and Thames Valley Railway (M&TVR), and planned to make a railway for passengers and goods connecting to the metropolis, as well as to Chertsey for westward connection, and they contemplated mixed gauge. This hugely ambitious scheme needed a friendly sponsor, but the GWR was ungenerous, and the LSWR, desperate to keep the broad gauge rails out of its territory, agreed working arrangements only for a branch from the LSWR Twickenham to Kingston arc to Shepperton. Altering its name to a more realistic Thames Valley Railway (TVR), it obtained an authorising Act on 17 July 1862.

Many original supporters were disappointed at the limited scope of the proposal and withdrew, but the line opened as a single line on 1 November 1864, from Thames Valley Junction (now 'Strawberry Hill' or 'Shacklegate'). The line was now effectively a branch of the LSWR and amalgamation was formalised, effective from 1 January 1867. Doubling from the junction to Fulwell was probably completed in the same year, and in stages the whole line was doubled by 9 December 1878.[31]

Chertsey Loop and GWR link

Residents of the market town had long complained about their station, which was a terminus on a branch from Weybridge. On 23 June 1864 powers were included in the LSWR's Act to build a line from Virginia Water to Chertsey connecting end-on with the existing branch, and to re-site the station to the north of Guildford Road level crossing. Virginia Water already on an 'independent' railway worked by the LSWR, led to trains to Reading as well as Staines through a triangle junction there. The line opened on 1 October 1866; it was double track except for the westward spur at Virginia Water.[32]

Leatherhead

The original Leatherhead station on the Epsom & Leatherhead Joint line was described as temporary, and was inconveniently far from the town centre, north-east of Kingston Road. In 1863 the LB&SCR promoted a Bill to extend to Dorking, with a new station in Leatherhead itself. The LSWR requested that the extension and station should be joint like the E&LR line, but the LBSCR were unwilling. A compromise was reached in which land would be purchased, sufficient for both companies to have stations alongside one another; the LB&SCR station was to be aligned towards Dorking, and the LSWR station towards a possible later extension to Guildford. The LSWR part of this arrangement was authorised by Act of 25 July 1864 and the new stations and double track throughout the E&LR, opened on 4 March 1867.[32]

Kingston to Malden

The LSWR Kingston branch approached from the north in a wide arc; now in 1865 the company proposed to connect the town to a widened original main line, crossing Richmond Road by a level crossing, and passing under the main line near the present New Malden, running eastwards alongside the main line to Wimbledon. An Act of 16 July 1866 modified the scheme, authorising the high-level, through station at Kingston and crossing Richmond Road by a bridge. The line opened on 1 January 1869 including its Norbiton station and at Malden it burrowed under the main line and ran to Wimbledon on the south side of the line, being joined by the Epsom branch at the present Raynes Park and the Tooting Merton and Wimbledon line immediately west of Wimbledon station. There seems to have been no connections between the double track for the branches and the main line at any point west of Wimbledon itself.[33][34]

After 1870

In the decade ending in 1870, considerable infilling of the suburban network had taken place; many communities formerly feeling themselves to be inadequately served, now had their own station. Strategically the LSWR had preserved most of the territory it considered its own. The penetration of the Metropolitan Railway and the Metropolitan District Railway in the area around Hammersmith was a borne financial blow. The Richmond and Hammersmith competitors until 1898 could exploit weak Waterloo-City connections, but this had been mitigated by accords with the LB&SCR and LC&DR giving access to Ludgate Hill. Laying new lines further afield, the LSWR moved at closer range to improving its diverse network. There remained one major challenge.

Putney to Wimbledon

As residential travel continued to increase, new and existing railways considered whether new territory, or a share of the business at places already served, could be exploited. At the same time, residents of increasingly 'commuter towns', particularly Kingston upon Thames, made great play of their poor City connections compared to rival towns like Richmond. The District Railway had opened as far as Fulham (Walham Green) in 1880 and was contemplating an extension from there to Guildford, striking through LSWR territory and serving many suburban towns that the LSWR considered its own, including Kingston. The LSWR managed to form an alliance with the District, under which a Kingston and London Railway would be constructed, from Surbiton via Kingston and Richmond to Putney, crossing the Thames and joining the District. Mutual running powers were to be agreed, giving the LSWR access to South Kensington and High Street Kensington.

Successive unexecuted plans saw authorising Acts such as on 22 August 1881: the K&LR's authorising Act permitted building from the District Railway at Putney Bridge, across the river and over Putney Heath and Wimbledon Common to the south side of the LSWR at Surbiton; the District Railway and the LSWR were authorised to acquire the K&LR jointly. In the same session the LSWR obtained powers to build a West End terminus adjacent to the District's South Kensington station. Also in that session, the Wimbledon and West Metropolitan Railway was authorised on 18 August 1882, to build a branch from the K&LR line at East Putney to join the TMW line at Haydons Road, getting access to Wimbledon station from there. The District Railway secured running powers over this line.

The District Railway did not have the money to fund its share of the K&LR construction, and after much wrangling, the LSWR agreed to take over the construction only of the section of the K&LR from Putney Bridge (District Railway) to East Putney, and a modified version of the W&WMR from there to Wimbledon station (instead of Haydons Road). There was also to be a flying junction at East Putney to the Richmond line towards Wandsworth.

Keeping the invader away from Kingston was a great victory for the LSWR but they had to build the Thames river bridge at Putney themselves. They charged the District Railway for use of the bridge and chose to abandon all plans for using the line themselves and for an independent South Kensington terminus..

On 3 June 1889 District Railway trains started operation, using a separate two-platform station on the north side of the LSWR station at Wimbledon. On 1 July 1889 the spurs to the Wandsworth line at East Putney were opened, and the LSWR started operating passenger trains from Waterloo to Wimbledon, running to the LSWR main station there.[31][35]

Windsor to Woking

The LSWR had leased the Staines, Wokingham and Woking Junction line from the outset, but found relations with the owning company difficult. At the same time Ascot was growing in importance, and a southward branch from there to Aldershot was being planned. By Act of 4 July 1878, the LSWR purchased the company.

The LSWR obtained authorisation on 20 August 1883 to build a mprth-west curve at Staines, allowing through running from Windsor to Virginia Water and beyond either west or south. This opened on 1 July 1884, and at the same time a new station, Staines High Street, was opened, as trains using the new curve would by-pass the existing Staines station. The same Act authorised a west curve at Byfleet, enabling direct running from Chertsey towards Woking, and this opened on 10 August 1885, although it appears not to have had a regular train service until 4 July 1887.[32]

Main line widenings

For some years after the opening of the main line, little attention could be given to developing the new network and extensions and additions were made incrementally, with little attempt at proper integration. The ramshackle state of the Waterloo terminal was testimony to this, but the growth of traffic poses major challenges in operating the main line .

Nine Elms was the chief goods terminal for London with extensive sidings and yards. Locomotive workshops were here on the south side, part of which was absorbed in the mid-1870s by a new main line viaduct between the Wandsworth Road tunnel and New Road (now Thessaly Road). The four track main line was diverted progressively, tracks opening between 22 October 1877 and 21 July 1878. Widening followed westward (Queens Road (Battersea) to 'Clapham Junction') on 1 November 1877.

Since the opening of the Epsom line there had been four tracks between Wimbledon and the present-day Raynes Park. This extended to the next stop when the Kingston line opened; arranged as two double track parallel railways. Here both tracks for the Kingston loop-with-branch went under the main line to progress north-westwards.

Here a double-line junction (at the west end of Coombe & Malden station (i.e. New Malden)) was passed by the Board of Trade on 24 April 1880, enabling the four tracks to act roughly as a four-track line. Quadrupling throughout between Clapham Junction and Hampton Court Junction was progressively completed by 1 April 1884, with the tracks paired by direction (Up Local, Up Through, Down Through, Down Local.[note 10]) A new spur was provided at Malden for the loop-with-branch and a new tunnel at Raynes Park brought the Up Epsom line under the main line to join the Up Local Line, burrowing junctions.

Accordingly, a new combined and extended Wimbledon station north-east of Wimbledon Bridge was opened, on 21 November 1881, and terminus for the Metropolitan District Railway's trains.[30][32]

By 1890 to Hampton Court Junction was four-track and three-track (only one down) to Woking.[36]

A New Line to Guildford

Residents of Cobham had long called for a railway, and a number of schemes were put forward, and failed. After a complex of schemes, Acts in 1881, 1882 and 1883 authorised what became the Guildford New Line, running from the main line at Long Ditton via Cobham, with a branch from the Leatherhead terminus joining it at Effingham, without a junction station until 1885.[32] Although the line was planned to serve local stations only, it gradually received through Portsmouth trains in the final years of the nineteenth century.[36]

Twickenham junctions

The Shepperton branch had been served from the north at Thames Valley Junction, so that direct running from Kingston was not possible. This was rectified when the south curve from Shacklegate Junction to Fulwell was opened on 1 July 1894,[37] Advertised passenger operation did not start until 1 June 1901.[38]

A Twickenham flyover, leading the up line from Shepperton and Kingston over the Ascot line was opened on 22 October 1883. This was the first grade-separated junction on the LSWR.[32]

Tooting lines

Tooting station was moved east of London Road on 12 August 1894.[30]

Waterloo & City Railway

After a couple of fanciful independent proposals, the Waterloo & City Railway company was promoted, obtaining its enabling Act in 1893. Independent, but supported by the LSWR as a tube railway, that is, constructed by boring and using cast iron segments to line the tunnel. Using compressed air and the Greathead tunnelling shield, the line was constructed in twin tubes, passing under the River Thames and terminating at the Mansion House, in a common station provided by the Central London Railway. The station was also used by the City and South London Railway.

The line used electric traction at 500 v d.c. with a central live rail, and had only two stations: Waterloo, and City (later renamed Bank). It opened to the public on 8 August 1898. Through tickets and season tickets from LSWR surface stations were (as they are) available. The LSWR operated it, and later absorbed it.[13]

The twentieth century

If the closing years of the nineteenth century had seen a relaxation of the battle to secure territory and fend off competing lines, two new threats now arose: electric passenger trains and street tramways. As well as the developments that were actually implemented (see below) the Metropolitan Railway and the Central London Railway both developed schemes in the years running up to 1914 for extensions of traffic, or new routes, into LSWR territory.

Loss of traffic to street tramways was increasingly felt at the turn of the century, due to their convenience, frequency and cheap fares. Lost traffic was to the District and LNW Railway's Richmond services leading to a loss-making operation on the indirect metropolitan LSWR routes, especially the Richmond service via Kensington and Hammersmith, and the Ludgate Hill service via Streatham was undercut.

Tube lines

The City and South London Railway (opened 1890) was the first deep-level tube railway in the world[39] closely followed by the Central London Railway and the Waterloo and City Railway. A minor tube railway mania followed, threatening LSWR territory, proving complimentary rather than competing: the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway provided better access from Waterloo to the 'West End'. However they demonstrated that electric haulage was superior to steam haulage in enabling a clean air environment at stations and in the trains, as well as technical benefits of increased acceleration and cheaper running.

District Railway

At the outset of the twentieth century, the Metropolitan District Railway (MDR) was planning to run electric trains to Wimbledon from Putney Bridge, extending its existing service. With LSWR co-operation the four-rail electrification was installed and District electric trains reached there on 27 August 1905. The line voltage was 600 v d.c.

This led to a proposal for the MDR to extend from Wimbledon to Sutton, and to quadruple the Putney to Wimbledon section which was already suffering from congestion. The idea was eventually dropped, but intermediate block posts were provided between Putney and Wimbledon to reduce section time and increase capacity.

The MDR finally began to run on the LSWR line between Studland Road Junction (Hammersmith) and Turnham Green. This too was electrified, with the MDR Ealing service running as electric trains from 1 July 1905, and the Richmond service on 1 August 1905. The considerably enhanced and frequent train service operated by the MDR led them to propose quadrupling the track on this section. This was agreed and it opened for operation on 3 December 1911, with a burrowing junction at Turnham Green for Up District trains; the gradient was steep for goods, at 1:50 so a flat junction was provided, eastward, for Midland Railway coal trains.[36]

LNWR electric trains

From 1911 the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) proposed electrifying its North London Railway, which it managed. It came to an arrangement with the LSWR whereby the latter's part of the routes to Richmond and Kew Bridge would be electrified for the LNWR trains (where they were not already electrified for the District Railway trains). The LNWR electric service started on 1 October 1916.

Closure of the Studland Road, Tooting and Staines West curve services

Declining traffic on the passenger trains via Kensington and Richmond via Studland Road Junction, and wartime stringency, led to their ending on 5 June 1916; they had already been cut back to start from Clapham Junction instead of Waterloo. The LSWR track (Hammersmith to Turnham Green) was transferred to the Underground group for the extension of the Piccadilly line in 1932.[40]

The Wimbledon - Tooting - Herne Hill - Ludgate Hill service was discontinued from 1 January 1917, and the LB&SCR local trains from Wimbledon to Streatham were also curtailed, leaving that route section with no passenger service. The LSWR was restored on 27 August 1923 (under LSWR's amalgamated successor).

The Windsor to Woking service was withdrawn on 31 January 1916 so Staines High Street station, on the mothballed Staines West Curve, was demolished.[36]

Hampton Court Junction

In the late 1880s, Hampton Court was a flat junction serving main lines (see widening, as well as the Hampton Court branch and the Guildford New Line via Cobham. Powers were taken (20 July 1906) to provide a grade-separated junction: the Up Cobham line was brought under the main line and opened on 21 October 1908 and the more expensive flyover for the Hampton Court branch, ascending on viaduct from Surbiton station opened 4 July 1915.[36]

Electrification of the LSWR network

The LSWR had been slower than competing lines to plan electrification,[note 11] and it was the LB&SCR among the railways south of London that electrified some of its suburban lines, with the first opening on 1 December 1909. Street tramways and competing, electric railways, coupled with demographic factors, led to losses of income year on year which were becoming serious, such that London area fares were reduced from 1 January 1914 to try to stem the loss.[36]

The passive conservatism of the LSWR ended when Herbert Ashcombe Walker was appointed to the post of General Manager from 1 January 1912. Realising that electrification was essential to success, he promoted Herbert Jones to the post of the company's Electrical Engineer. He sent Jones to New York to look particularly at DC third-rail installations in use on urban railroads there.[note 12][41]

Jones and Walker reported to the Board on 6 December 1912, and the Board approved the largest electrification scheme thus far authorised by any railway.[36] The routes to be converted to electric operation were all suburban or "outer suburban" and would be dealt with in two stages: the first stage would cover:

- Waterloo - Hounslow Loop - Waterloo (done 12 March 1916)

- Waterloo - Kingston Loop - Waterloo

- The Shepperton branch (done 30 January 1916)

- Point Pleasant Junction (on the Clapham Junction to Barnes line) - East Putney - Wimbledon (done 25 October 1915)

- The main line to Hampton Court Junction and the branch to Hampton Court (done 18 June 1916)

- New Guildford Line to Claygate.(done 20 November 1916)[41][42]

The last short investment allowed train reversal and interchange, clear of the busy main line.

The LSWR proceeded without a new Act, on the basis that the incorporating London & Southampton Railway Act did not limit the choice of traction mode.

The Company opted to build its own power generating station, at Durnsford Road, a little east of Wimbledon, and five 5,000 kW turbo-generators were installed, generating three-phase electricity at 11 kV 25 Hz. This was distributed by lineside cables to sub-stations at Waterloo, Clapham Junction, Raynes Park, Kingston, Twickenham, Barnes, Isleworth, Sunbury and Hampton Court Junction which transformed the 11 kV to 600 v and converted it to d.c. using rotary converters needing constant manning while trains were running.

On the track, a third rail of high conductivity steel was laid outside the four-foot; the return current travelled through the running rails; impedance bonds were provided at track circuit joints, and the track circuits had to be altered to a.c. operation.

The line voltage was 600 v positive d.c. nominal; where the North London Railway and District Railway trains ran over LSWR tracks they used a four rail system, with the outer rail at +300 v and the centre return rail at -300 v; this had to be altered to conform to the LSWR standard, and some alterations were required to the trains of the penetrating companies.

As part of the work, the route between Vauxhall and Nine Elms was widened to eight tracks, and the flyover at Hampton Court Junction was now constructed.

The rolling stock consisted of 84 three-car units, all the coaches being converted from steam stock.

Electric operation advantages

The trains operated on a regular interval timetable, at first the same frequency through the peak hours, with the train formations being strengthened at those times. The new electric service was a considerable success, and there was some overcrowding. The Guildford new line was served by push-and-pull trains connecting with the electric trains at Claygate, but to release electric stock to strengthen trains in the core electric area, the Claygate service was discontinued (and reverted to steam operation). This was done in July 1919, and the Claygate line did not receive regular electric trains until the entire Guildford New Line was electrified in 1925.[42]

From 1919 additional capacity was created by converting further steam stock to two-car trailer units, to operate between two ordinary three-car units, forming an eight-car train. It had been found that the three-car units had power to spare. The trailer units had no driving compartment.

World War I and following British industrial shortage prevented progress: the second stage of electrification, covering the outermost suburban lines; and a grade-separated junction at Woking, but this was deferred (and never built). There was no further LSWR electrification before the Grouping of the railways under the Railways Act 1921 by which the Southern Railway was created from the LSWR, the LB&SCR, the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SE&CR), and some minor lines; this took effect 1 July 1923.[note 13]

The Grouping was known about well before its implementation—for a time, nationalisation had seemed a possibility—but this did not quell electrical and operational bigotry. The LB&SCR were anxious that their 6.7 kV overhead system should be adopted as the standard, and at this time the SE&CR had been planning electrification of its system on a 3 kV overhead system.[41]

Rolling stock: electric units

The original 84 cars ran as "bogie-block" sets, semi-permanently coupled, built at Eastleigh between 1902 and 1912. They were wooden bodies with semi-elliptical roofs.

The conversion was carried out at Eastleigh works, and the electrical equipment where much of the body and running gear conversion was carried out by the British Westinghouse Electrical and Manufacturing Company.

The formation was two motor coaches with a driving compartment and "brake" compartment at the outer ends, with a trailer between them. The outer bogie at each end of the unit was a motor bogie fitted with two axle-hung[note 14] traction motors rated at 275 hp (205 kW). A bus line[note 15] ran along the roof of the unit connecting all the current collector shoes, and if two units were coupled, connected the entire train.

The master controller had four positions: switching, full series, parallel, and full parallel. Control equipment shunted out starting resistances automatically as speed increased and current drawn fell. In practice drivers could move the controller to full parallel immediately on starting, and the control equipment would lower resistance without intervention. The notching process produced a series of sharp clicks, and the units were nicknamed "nutcrackers" from this cause. The specified maximum running speed was 52 mph (84 kph), although a maximum speed in service of 40 mph (64 kph) was imposed due to rough riding at higher speeds.

The Westinghouse quick-acting brake was installed in place of the automatic vacuum brake as it allowed faster stops and restarting, important for a high-frequency urban railway. Within the unit the couplings were semi-permanently fixed with a bar coupling, but conventional couplings were provided at unit ends; in addition were the power jumper for the bus line and an eight-core control cable, as well as the Westinghouse brake pipe coupling.

For reasons of style, the units were given a blunt torpedo shaped end with a domed roof at the ends; a new livery was provided, of sage green, with black and yellow lining and mid-brown window mouldings, and the roof was coloured off-white. The width over body was 8 ft 0¾ in (2.46 m), and 8 ft 10¾ in (2.71 m) over handles. An external opal panel was provided at each end of the unit between the motorman's windows, for a stencil plate, a letter indicating the route (which was illuminated at night).

The units only provided first and third class accommodation all in compartments.[41]

Trailer units

The success of the new electric service was such that severe overcrowding took place at busy periods, and in 1919 the LSWR decided to build some two-car trailer units. The electric units had plenty of power and steam coaching vehicles were cheaply converted, so that eight-car trains could be formed by inserting one trailer between two three-car electric units. To shunt such trailer units off at the end of the busy periods was a difficult procedure therefore, but they were a cheap and quick expedient to relieve the overcrowding. 24 of these units were built in the period January 1920 to December 1922.[41]

Southern Railway

The LSWR suburban network was working profitably and the Southern Railway continued and later extended the electrified system. The LSWR configuration of third rail operation at 600 v d.c. (later gradually increased to 750 d.c.) became the standard for the whole electrified network of the Southern Railway and later (after 1948) of the British Railways system in the southern counties, eventually reaching the coast at Ramsgate, Brighton, and Weymouth.

Wimbledon architectural improvement

Wimbledon station was completely reconstructed, seamless to its street like Richmond, 1927-8, combining the joint LB&SCR section and the District Railway sections, retaining identifiably distinct platforming arrangements.[30]

Durnsford Road flyover

When the main line was quadrupled in the early years of the twentieth century, the tracks allocated to stopping trains were on the outside with the main lines in the centre: "pairing by direction". This makes the main lines safe everywhere except at one point: that local trains must cross both main lines (before or after a terminus) to account for their change in direction. This made sufficient gaps relatively short, even given advanced signalling.

To cure delays a flyover was built east of Wimbledon, carrying the north outer line across the two central lines, so that from there to Waterloo up and down slow lines were on the south side "paired by use". The new layout was brought into use on 17 May 1936.[30]

Chessington line

From 1923 considerable housing development took place in the area that came to be served by the Chessington branch, built by the successor. It was originally planned to extend to Leatherhead, joining the existing route there.

It left the Dorking line at Motspur Park and it was opened on 29 May 1938 to Tolworth, with an intermediate station at Malden Manor. The following year, on 28 May 1939, it was extended to Chessington North and Chessington South, its stations being built of Art Deco sculpted concrete, typical of the Southern Railway's design investment in the period, epitomised by Surbiton (which has a protected status).

Plans to extend were thwarted by the Second World War.[43]

Notes

- ↑ Gilks, writing in 1958, puts the first station on the west side of Ewell Road but this seems to be a mistake; he appears to justify this from the location of the (former) Railway Tavern, which was in the angle of Ewell Road and Lamberts Road, and from South Terrace, which he says was "probably the approach road for the old station and the circular stone steps which now begin the path from there to the present station contrast strongly with the rest of the path and may well mark the original entrance"

- ↑ Roughly where platforms 9 to 12 are at present.

- ↑ Neither curves are in use today.

- ↑ Nowadays competition law would prohibit such arrangements.

- ↑ Carter refers to this as the Staines, Wokingham and Reading Railway, as does Bradshaw's Railway Manual for 1867.

- ↑ There were signs that the LC&DR was concerned that it had over-extended itself and that it was glad of the capital injection that the LSWR (and incidentally the Great Northern Railway) provided. Mitchell and Smith say that "The LSWR lent the impoverished LC&DR substantial sums to complete their line".

- ↑ Carter says it was originally intended to reach Epsom

- ↑ Williams, volume 2, says that the scope was from a junction with the LC&DR at Camberwell, but this seems to be a mistake.

- ↑ Butt gives 'Haydens', Ordnance Survey maps from before and after opening 'Haydons'.

- ↑ It is not certain that this naming convention was applied at this date

- ↑ Discounting the electric Waterloo & City Railway

- ↑ The LB&SCR system used a higher voltage and overhead line current collection; this required considerable expenditure on structures to support the overhead equipment.

- ↑ Planned for 1 January 1923, legal difficulties delayed the formal implementation until July.

- ↑ The term was not yet in general use (the electric motors were supported on brackets fixed to the driving axle rather than on the (sprung) bogie frame.)

- ↑ A continuous electric connection that serves multiple sources and machines

References

- ↑ R A Williams, The London & South Western Railway, Volume 1: The Formative Years, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1968, ISBN 0-7153-4188-X, Chapter 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Williams, chapter 6

- ↑ Williams, Volume 1, page 122

- ↑ 'Kingston upon Thames' A Topographical Dictionary of England. Ed. and Pub. Samuel Lewis (publisher). London: 1848. 680-683. British History Online. 12 January 2015.

- ↑ The Year-Book of Facts in Science and Art, Tilt and Bogue, London, 1841

- 1 2 Ordnance Survey maps, e.g. 1:2,500, 1869 etc.

- ↑ Gillham, page 7, implying it was the station name

- ↑ C Hamilton Ellis, The South Western Railway, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, London, second impression, 1962

- 1 2 3 4 5 E F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London, 1959

- 1 2 3 4 Sam Fay, A Royal Road, 1973 reprint of 1882 original, E P Publishing, Wakefield, ISBN 0 85409 769 4

- ↑ Ordnance Survey Town Plan of London, 1:5280, dated 1850

- ↑ Ordnance Survey Town Plan of Richmond, 1:1056, dated 1867

- 1 2 3 4 John C Gillham, The Waterloo & City Railway, The Oakwood Press, Usk, 2001, ISBN 0 85361 525 X

- 1 2 3 4 H P White, London Railway History, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1963 revised 1971, ISBN 0 7153 6145 7

- 1 2 3 Col M H Cobb, The Railways of Great Britain -- A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Publishing Limited, Shepperton, 2003, ISBN 07110 3003 0

- 1 2 3 R V J Butt, The Directory of Railway Stations, Patrick Stephens Limited, Sparkford, 1995, ISBN 1 85260 508 1

- 1 2 J Spencer Gilks, Railway Development at Kingston-upon-Thames — 1 in the Railway Magazine, July 1958

- 1 2 3 Joe Brown, London Railway Atlas, second edition, 2010, Ian Allan Publishing Ltd, Hersham, ISBN 978 0 7110 3397 9

- ↑ The Illustrated London News, 19 April 1856

- 1 2 3 Williams, Chapter 5

- ↑ Mitchell & Smith, London Suburban Railways, West Croydon to Epsom, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 1992, ISBN 1 873793 08 1

- ↑ Bradshaw's Railway Manual, 1857, reported that "The branch to Woking is not yet commenced, and a bill is being promoted for its abandonment." The proposal is not further described by Carter or Williams.

- ↑ Bradshaw's Railway Manual, Shareholder's Guide and Official Directory for 1867, Vol XIX, London and Manchester, 1867

- 1 2 3 4 R A Williams, The London and South Western Railway, Volume 2: Growth and Consolidation, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1973, ISBN 0 7153 5940 1

- ↑ Adrian Gray, The London, Chatham & Dover Railway, Meresborough Books, Rainham, 1984, ISBN 0-905270-88-6

- ↑ Mitchell & Smith, West London Line: Clapham Junction to Willesden Junction, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 1996, ISBN 1 873 793 84 7

- ↑ Williams, page 180

- ↑ Christopher Awdry, Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies, Patrick Stephens Ltd, Sparkford, 1990, ISBN 1-8526-0049-7

- ↑ John Henry Fawcett, A Treatise on the Court of Referees in Parliament, published by Horace Cox, London, 1866

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mitchell & Smith, London Suburban Railways—Lines Around Wimbledon, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 1996, ISBN 1 873793 75 8

- 1 2 Williams, volume 2, chapter 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Williams, volume 2 chapter 2

- ↑ Williams, volume 2, page 38

- ↑ From inspection of the 1:2,500 Ordnance Survey plans of the period

- ↑ Alan A Jackson, London's Local Railways, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1978, ISBN 0 7153 7479 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Faulkner & Williams, The LSWR in the Twentieth Century, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1988, ISBN 0 7153 8927 0

- ↑ Williams volume 2, page 43

- ↑ Faulkner & Williams, page 41

- ↑ Christian Wolmar, The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever, Atlantic Books, 2004, ISBN 1-84354-023-1.

- ↑ Faulkner & Williams, page 40

- 1 2 3 4 5 David Brown, Southern Electric, volume 1, Capital Transport, St Leonards, 2009, ISBN 978-1-854-143303

- 1 2 J Spencer Gilks, Railway Development at Kingston-upon-Thames — 2, in the Railway Magazine, August 1958

- ↑ Mitchell & Smith, Wimbledon to Epsom, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 1995, ISBN 1 873 793 62 6