Kwalliso

| Political penal-labour colony | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 관리소 |

|---|---|

| Hancha | 管理所 |

| Revised Romanization | gwalliso |

| McCune–Reischauer | kwalliso |

|

Literally "place(s) of custody" (kwalli can also mean "administration", "maintenance" or "care", and the whole term is usually translated as "management centre" in other contexts than North Korea's penal system) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Human rights in North Korea |

|---|

|

|

International reactions |

North Korea's political penal labour colonies, transliterated kwalliso or kwan-li-so, constitute one of three forms of political imprisonment in the country, the other two being what Hawk (2012)[1] which is translated as "short-term detention/forced-labor centers"[2] and "long-term prison labor camps"[3] for misdemeanour and felony offences respectively.[1] In total, there are an estimated 80,000 to 120,000 political prisoners.

In contrast to these other systems, the condemned are sent there without any form of judicial process as are their immediate three generations of family members in a form of sippenhaft. Durations of imprisonment are variable, however, many are condemned to labour for life. Forced labour duties within kwalliso typically include forced labour in mines (known examples including coal, gold and iron ore), tree felling, timber cutting or agricultural duties. Furthermore, camps contain state run prison farms, furniture manufacturing etc.

Estimates suggest that at the start of 2007, a total of six kwalliso camps were operating within the country. Despite fourteen kwalliso camps originally operating within North Korea, these later merged or were closed following reallocation of prisoners.[4]

Population

There are currently between 80,000 and 120,000 political prisoners in kwalliso.[5] The number is down from 150,000–200,000 during the 1990s and early 2000s,[6] due to releases and deaths.[5] The earliest estimates were from 1982, when the number was thought to be 105,000.[6]

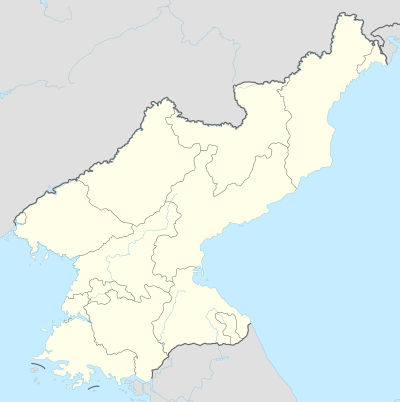

Camp locations

North Korea's kwalliso consist of a series of sprawling encampments measuring kilometers long and kilometers wide. The number of these encampments has varied over time. They are located, mostly, in the valleys between high mountains, mostly, in the northern provinces of North Korea. There are between 5,000 and 50,000 prisoners per kwalliso.

The kwalliso are usually surrounded at their outer perimeters by barbed-wire fences punctuated with guard towers and patrolled by heavily armed guards. The encampments include self-contained, closed "village" compounds for single persons, usually the alleged wrongdoers, and other closed, fenced-in "villages" for the extended families of the wrongdoers.

The following lists the operating kwalliso camps:

- Prison camp No. 14: Kaech'ŏn, South Pyongan province.

- Prison camp No. 15: Yodŏk, South Hamgyong province.

- Prison camp No. 16: Hwasŏng, North Hamgyong province.

- Prison camp No. 18: Pukch'ang, South Pyongan province.

- Prison camp No. 22: Haengyŏng, Hoeryŏng County, North Hamgyong province.

- Prison camp No. 25: Ch'ŏngjin, North Hamgyong province.

Camp closures

Notable kwalliso closures are listed below:[7]

- In 1989, Camp No. 11 in Kyŏngsŏng County, North Hamgyong Province was closed. Approximately 20,000 family prisoners were transferred to other political penal-labour camps.

- Prison camp No. 12 in Ch'angp'yŏng, Onsŏng County, North Hamgyong Province was also closed in 1989 because the camp was deemed too close to the Chinese border.

- At the end of 1990, Camp No. 13 in Chongsŏng, also Onsŏng County, was closed. Approximately 30,000 prisoners were relocated after fears that the camp was located too close to the Chinese border.

- Camp No. 27 at Ch'ŏnma, North Pyong-an Province was closed in 1990.

- Camp No. 26 in Sŭngho's Hwachŏn-dong was closed in January 1991.

- Between 2003 and 2007 it is thought that an additional three camps were closed.

Legislative structure

The kwalliso are run by a secret police agency and are therefore not specifically tied to the laws and courts of the North Korean government. However, each camp is expected to operate in strict accordance with state Juche ideology.

Operating principles

Detainees are regularly told that they are traitors to the nation who have betrayed their Leader and thus deserve execution, but whom the Workers' Party has decided, in its mercy, not to kill, but to keep alive in order to repay the nation for their treachery, through forced labour for the rest of their lives. The emphasis of these camps is very much placed upon collective responsibility where individuals ultimately take responsibility for their own class' "wrong doing". Kwalliso guards emphasize this point by reportedly carving excerpts from Kim Il-sung's speeches into wood signs and door entrances. Work teams are given stringent work quotas, and the failure to meet them means even further reduced food rations.[4]

Working conditions

Below-subsistence level food rations coupled with hard, forced labour results in a high level of deaths in detention not only as a result of working to death but also by rife disease caused by poor hygiene conditions. Corn rations are the usual staple diet of any prisoner but these may be supplemented by other foods found during labour such as weeds and animals. Each five-person work group has an informant, as does every prison camp "village".[4] Survivors and commentators have compared the conditions of these camps to those operated in Central and Eastern Europe by Nazi Germany during World War II in the Holocaust calling the DPRK's network of political prison camps the North Korean Holocaust.[8][9][10][11][12]

Internment of prisoners

Defector statements suggest prisoners come to the camps in two ways:

- Individuals are likely taken and escorted by the State Security Department, detained in small cells and subjected to intense and prolonged interrogation, involving beatings and severe torture, after which they are dispatched to one of the prison labour camps.

- Family members: The primary suspect in the family is firstly escorted to the prison camp, and the Bowibu officers later escort family members from their home to the encampment. Family members are usually allowed to bring their own goods with them into the camp however these are usually only used by prisoners as bribing commodities later on.

Encampment outlay

Guard towers and barbed wire fences usually demark camp boundaries apart from where terrain is impassable. Prisoners are housed within scattered villages usually at the base of valleys and mountains. Single inhabitants are sub grouped accordingly into an assigned communal cafeterias and dormitories and families are usually placed into shack rooms and are required to feed themselves.

Zoning of prison camps

Areas of the encampments are zoned or designated accordingly for individuals or families of the wrong-doers or wrong-thinkers. Both individuals and families are further sub divided accordingly into either a "revolutionary processing zone" or "total control zone":[4]

- The "revolutionary processing zone" (Chosŏn'gŭl: 혁명화구역; MR: hyŏngmyŏnghwa kuyŏk) accommodates prisoners having the opportunity of future release from the camp back into society. Thus these prisoners are likely re-educated in so called "revolutionizing" areas of the camp – tasks include forced memorization of speeches by Kim Il Sung with specific emphasis placed on re-education of children. A revolutionary processing zone is thought to be operating in Pukch'ang concentration camp and also at Yodŏk concentration camp in South Hamgyong Province.

- There is no reported re-education of prisoners in "total control zones" (Chosŏn'gŭl: 완전통제구역; MR: wanjŏn t'ongje kuyŏk) presumably because these prisoners are not seen fit to be released and are deemed counter-revolutionary.

Awareness

Statements taken from North Korean defectors suggest that despite the secretive nature of these labour camps, North Koreans are aware of a system (at the very least) of camps in existence and are known to refer to political prisoners as "people who are sent to the mountains".[1]

Demand for closure

Amnesty International summarize the human rights situation North Korea's kwalliso camps: "Men, women and children in the camp face forced hard labour, inadequate food, beatings, totally inadequate medical care and unhygienic living conditions. Many fall ill while in prison, and a large number die in custody or soon after release." The organization demands the immediate closure of all other political prison camps in North Korea.[13] The demand is supported by the International Coalition to Stop Crimes against Humanity in North Korea, a coalition of over 40 human rights organizations.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Hawk, David. "The Hidden Gulag – Exposing North Korea's Prison Camps" (PDF). The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- ↑ Chosŏn'gŭl: 집결소; Hancha: 集結所; RR: jipgyeolso; MR: chipkyŏlso, literally "place(s) of gathering"

- ↑ Chosŏn'gŭl: 교화소; Hancha: 敎化所; RR: gyohwaso; MR: kyohwaso, literally "place(s) of reeducation"

- 1 2 3 4 Hawk, David. "Concentrations of Inhumanity" (PDF). Freedom House. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- 1 2 United Nations Human Rights Council Session 25 Report of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea A/HRC/25/63 page 12 (paragraph 61). 7 February 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- 1 2 United Nations Human Rights Council Session 25 Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea A/HRC/25/CRP.1 page 226 (paragraph 749). 7 February 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "1. History of Political Prison Camps (p. 61 - 428)". Political Prison Camps in North Korea Today (PDF). Database Center for North Korean Human Rights. July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Sichel, Jared. "Holocaust in North Korea".

- ↑ Agence France Presse. "North Korean Prison Camps Are 'Like Hitler's Auschwitz'".

- ↑ Hearn, Patrick. "The Invisible Holocaust: North Korea's Horrible Mimicry".

- ↑ Weber, Peter, North Korea isn't Nazi Germany — in some ways, it's worse

- ↑ Judith Apter Klinghoffer. "The North Korean Holocaust. Yes. Holocaust.".

- ↑ "End horror of North Korean political prison camps". Amnesty International. May 4, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ↑ "ICNK Letter To Kim Jong Il". International Coalition to Stop Crimes against Humanity in North Korea. October 13, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

External links

- Committee for Human Rights in North Korea: The Hidden Gulag – Exposing Crimes against Humanity in North Korea’s Vast Prison System - Overview of North Korean prison camps with testimonies and satellite photographs

- Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea—detailed report, resources include maps and satellite photographs of camps

- Amnesty International: North Korea: Political Prison Camps - Document on conditions in North Korean prison camps

- "Political Prison Camps in North Korea Today" (PDF). Database Center for North Korean Human Rights. – Comprehensive analysis of various aspects of life in political prison camps

- Freedom House: Concentrations of inhumanity – Analysis of the phenomena of repression associated with North Korea’s political labor camps

- Christian Solidarity Worldwide: North Korea: A case to answer – a call to act – Report to emphasize the urgent need to respond to mass killings, arbitrary imprisonment, torture and related international crimes

- Washington Post: North Koreas Hard Labor Camps - Explore North Korean prison camps with interactive map

- Stanton, Joshua. "North Korea's Largest Concentration Camps on Google Earth". One Free Korea.