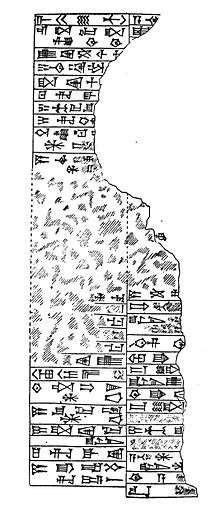

Kudurru of Kaštiliašu

The kudurru of Kaštiliašu' is a fragment of an ancient Mesopotamian narû, or entitlement stele, recording the legal action taken by Kassite king Kaštiliašu IV (ca. 1232–1225 BC) over land originally granted by his forebear Kurigalzu II (ca. 1332–1308 BC),[1] son of Burna-Buriaš II to Uzub-Šiḫu or -Šipak in grateful recognition of his efforts in the war against Assyria under its king, Enlil-nirari. Along with the Tablet of Akaptaḫa, these are the only extant kudurrus from this king’s short eight-year reign and were both recovered from Elamite Susa, where they had been taken in antiquity, during the French excavations under Jacques de Morgan at the end of the nineteenth century and now reside in the Musée du Louvre.

The stele

The surviving kudurru fragment is a crescent-shaped cross-section with convex surface inscribed with cuneiform and a concave side engraved with relief images.[2] Where the stele tapers to the top, it carries representations of the gods Sîn (crescent moon), Šamaš (solar-disc) and Ištar (eight-pointed star) in bas-relief. Beneath these a demon with a lion’s head, human body and short tail brandishes a knife in one hand and a club or mace in the other. This is Ugallu, “Big Weather Beast”, one of the eleven monsters who were to be conquered by Marduk in the later publication, Enûma Eliš, and who was to feature on apotropaic figurines of the first millennium BC. The seated dog figure of Gula is carved facing the demon.[3]

The broken text recalls that Kurigalzu had awarded an individual with the Kassite name Uzub-Šiḫu (or -Šipak, a Ksssite deity) a large area of 120 GUR (around 3.75 square miles) of agricultural land for services rendered during the war against Assyria.[4] This suggests a successful outcome in this conflict in marked contrast to the account espoused by the Synchronistic History, an Assyrian polemic chronicle inscription which boasts of Kurigalzu’s apparent defeat at the Battle of Sugagu, a view which was also contradicted in the Babylonian Chronicle P version of these events and also in Assyrian king Adad-nārārī I’s own recollections of his father, Enlil-nirari’s setbacks.

The text mentions Nimgirabi-Marduk, son of Nazi-…. and Pir-Šamaš, son of Šumat-Šamaš, but their roles are uncertain.[4] The land grant was reconfirmed by Kaštiliašu, possibly to a descendant of the original beneficiary, perhaps due to the failure to provide a sealed legal document during the earlier bequest.[5]

References

- ↑ J. A. Brinkman (1976). Materials and Studies for Kassite History (MSKH 1). Oriental Institute. p. 176. O.2.5

- ↑ Ursula Seidl (1989). Die Babylonischen Kudurru-Reliefs: Symbole Mesopotamischer Gottheiten. Academic Press Fribourg. p. 20.

- ↑ J. de Morgan; G. Jéquier; G. Lampre (1900). Mémoires de la Délégation de Perse, Vol. 1. Paris. pp. 178–179. fig. 386 kudurru IX.

- 1 2 V. Scheil (1900). Mémoires de la Délégation de Perse, Vol. 2. Paris. pp. 93–94.

- ↑ W. J. Hinke (1907). A New Boundary Stone of Nebuchadrezzar I from Nippur (BE IV). University of Philadelphia. p. 24.