Juan Marichal

| Juan Marichal | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Marichal in 2009 | |||

| Pitcher | |||

|

Born: October 20, 1937 Laguna Verde, Monte Cristi, Dominican Republic | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| July 19, 1960, for the San Francisco Giants | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| April 16, 1975, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 243–142 | ||

| Earned run average | 2.89 | ||

| Strikeouts | 2,303 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Inducted | 1983 | ||

| Vote | 83.7% (third ballot) | ||

Juan Antonio Marichal Sánchez (born October 20, 1937[1]) is a Dominican former professional baseball player. He played as a right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball most notably for the San Francisco Giants.[1] Marichal was known for his high leg kick, pinpoint control and intimidation tactics, which included aiming pitches directly at the opposing batters' helmets.[2]

Marichal also played for the Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Dodgers for the final two seasons of his career.[1] Although he won more games than any other pitcher during the 1960s, he appeared in only one World Series game and he was often overshadowed by his contemporaries Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson in post-season awards.[3][4] Marichal was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.[5]

Early life

Juan Marichal was born on October 20, 1937 in the small farming village of Laguna Verde, Dominican Republic, the youngest of Francisco and Natividad Marichal's four children.[6] He has two brothers, Gonzalo and Rafael, and a sister named Maria. His father died of an unknown illness when Marichal was three years old.[6] His house did not have electricity, but food was plentiful since his family owned a farm.[7] As a child, Marichal worked on the farm daily, and was responsible for taking care of his family's horses, donkeys, and goats.[7] He lived near the Yaque del Norte River, and often spent time swimming and fishing.[8] One day, while Marichal was playing by the river, he fell unconscious due to poor digestion, and was in a coma for nine days.[9] Doctors did not expect him to survive, but he slowly regained consciousness after his family gave him steam baths by doctors orders.[9]

His older brother Gonzalo instilled a love of baseball in young Marichal, and taught him the fundamentals of pitching, fielding, and batting.[10] Every weekend, Marichal played the sport with his brother and friends. For their games, they found golf balls and paid the local shoemaker one peso to sew thick cloth around the ball to make it the proper size.[11] They employed branches from a wassama tree for bats, and canvas tarps for gloves.[11] Among his childhood playmates were the Alou brothers, Felipe, Jesús, and Matty, who all later played with Marichal on the San Francisco Giants.[11] From the age of six, Marichal aspired to become a professional baseball player, but his mother discouraged this, instead urging him to get an education.[12] At the time, there were no players from the Dominican Republic in Major League Baseball, and his goal was viewed to be unrealistic.[12] At age 11, he briefly held a job cutting sugar cane for the J.W. Tatem Shipping conglomerate.

In 1954, sixteen-year-old Marichal joined a summer league in Monte Cristi, playing for a team called Las Flores.[10] Although he began at shortstop, Marichal switched to pitcher after taking inspiration from Bombo Ramos of the Dominican national team.[10] He left high school after being recruited to play for the United Fruit Company team in 1956.[13]

Playing career

Marichal's delivery was renowned for one of the fullest windups in modern baseball, with a high kick of his left leg that went nearly vertical (even more so than Warren Spahn's delivery).[3] Marichal maintained this delivery his entire career, and photographs taken near his retirement show the vertical kick only diminished. The windup was the key to his delivery in that he was consistently able to conceal the type of pitch until it was on its way.

Marichal was discovered by Ramfis Trujillo, the son of late Dominican dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo. Ramfis was the primary sponsor of the Dominican Air Force Baseball Team (Aviación Dominicana), against which Marichal pitched a 2–1 victory game in his native Monte Cristi. From the very moment the game ended, Marichal was a member of Aviación Dominicana team, enlisted to the Air Force right on the spot by Ramfis' orders.[14]

Marichal entered the major leagues on July 19, 1960 with the San Francisco Giants as the second native pitcher to come from the Dominican Republic. He made an immediate impression: in his debut, on July 19, 1960 against the Philadelphia Phillies, he took a no hitter into the eighth inning only to surrender a two-out single to Clay Dalrymple.[15] He ended up with a one-hit shutout, walking one and striking out 12.[16] He started 10 more games that season, finishing at 6–2 with a 2.66 ERA.[1] He improved his victory totals to 13 and 18 over the following two seasons, respectively, before finally cracking the 20-victory plateau in 1963, when he went 25–8 with 248 strikeouts and a 2.41 ERA.[1] He appeared in every All-Star game of the 1960s beginning in 1962. In May 1966, he was named NL Player of the Month with a 6-0 record, a 0.97 ERA, and 42 SO. On July 14, 1967, he surrendered the 500th Home Run of Eddie Mathews' career.

Marichal enjoyed similar success through the 1969 season, posting more than 20 victories in every season except 1967, and never posting an ERA higher than 2.76.[1] He led the league in victories in 1963 and 1968 when he won 26 games.[17][18] In 1968, he also finished in the highest rank of his career in MVP voting, finishing fifth behind Bob Gibson, Pete Rose, Willie McCovey, and Curt Flood. He and Sandy Koufax were the only two Major League pitchers in the post-war era (1946–present) to have more than one season of 25 or more wins; both pitchers had three such seasons in their careers.

Marichal won more games during the decade of the 1960s (191) than any other major league pitcher,[3] but did not receive any votes for the Cy Young Award until 1970, when baseball writers started voting for the top three pitchers in each league rather than one per league (or, until 1967, only the top pitcher in MLB). Marichal finished in the top 10 in ERA seven consecutive years, starting in 1963 and culminating in 1969, in which year he led the league.[19] During his career, he also finished in the top 10 in strikeouts six times, top 10 in innings pitched eight times (leading the league twice), and top 10 in complete games 10 times, with a career total of 244.[20] He led the league twice in shutouts, throwing 10 of them in 1965.[19][21]

Marichal exhibited exceptional control. He had 2,303 strikeouts with only 709 walks,[1] a strikeout-to-walk ratio of 3.25 to 1. This ranks among the top 20 pitchers of all time, ahead of such notables as Bob Gibson, Nolan Ryan, Steve Carlton, Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Walter Johnson and Roger Clemens, who each have strikeout-to-walk ratios of less than 3:1. Over his career, he led the league in the fewest walks per nine innings four times, and finished second three times – totaling eleven years in which he finished in the top 10, all while also finishing in the top 10 for strikeouts six years.

The Greatest Game Ever Pitched

One regular-season game in Marichal's career deserves mention, involving him and Milwaukee Braves' Hall of Famer Warren Spahn in a night contest played July 2, 1963, before almost 16,000 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. The two great pitchers matched scoreless innings until Giants outfielder Willie Mays homered off Spahn to win the game 1–0 in the 16th inning.[22][23] Both Spahn and Marichal tossed 15-plus inning complete games,[23] something that almost certainly will never happen again in the big leagues. Marichal allowed eight hits (all singles except for a double hit by Spahn) in the 16 innings, striking out 10, and saddling eventual career home run king Hank Aaron with an 0-for-6 collar.[23] Spahn permitted nine hits in 15 1⁄3 innings, walking just one (Mays intentionally, in the 14th, after Harvey Kuenn's leadoff double) and striking out two.[23] The game, almost the innings-duration of two contests, lasted only 4 hours, 10 minutes.[23] By coincidence, future Major League Baseball commissioner Bud Selig attended the game as a fan.[24]

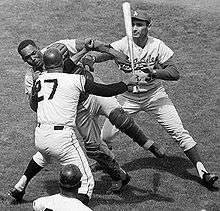

Roseboro incident

Marichal is also remembered for a notorious incident that occurred with John Roseboro during a game between the Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers at Candlestick Park on August 22, 1965.[25][26] The Giant-Dodger rivalry was, at the time, the fiercest in baseball - a rivalry which began when both teams played in the New York City market. [27] As the 1965 season neared its climax, the Giants were involved in a tight pennant race, entering the game trailing the Dodgers by a game and a half while the Milwaukee Braves were one game behind the Dodgers.[27] [28]

Maury Wills led off the game with a bunt single off Marichal and scored when Ron Fairly hit a double.[29] Marichal, a fierce competitor, viewed the bunt as a cheap way to get on base and took umbrage with Wills.[26][28] When Wills came up to bat in the second inning, Marichal threw a pitch directly at Wills sending him sprawling to the ground.[26] Willie Mays then led off the bottom of the second inning for the Giants and Dodgers' pitcher Sandy Koufax threw a pitch over Mays' head as a token form of retaliation.[26][28] In the top of the third inning with two outs, Marichal threw a fastball that came close to hitting Fairly, prompting him to dive to the ground.[28] Marichal's act angered the Dodgers and home plate umpire Shag Crawford warned both teams any further retaliations would not be tolerated.[28]

Marichal came to bat in the third inning expecting Koufax to throw at him. Instead, Marichal was startled when Roseboro's return throw to Koufax after the second pitch either brushed his ear or came close enough for Marichal to feel the breeze off the ball.[27] When Marichal confronted Roseboro, Roseboro came out of his crouch with his fists clenched.[27] Marichal later said he thought Roseboro was about to attack him. Marichal raised his bat, striking Roseboro at least twice on the head, opening a two-inch gash that sent blood flowing down the catcher's face. Roseboro later required 14 stitches. [27][30] Koufax raced in from the mound to attempt separate them and was joined by the umpires, players and coaches from both teams.[27] A 14-minute brawl ensued on the field before Koufax, Giants captain Willie Mays and other peacemakers restored order.[26] Marichal was ejected from the game and afterwards, National League president Warren Giles suspended him for eight games (two starts), fined him a then-NL record US$1,750[25][31] (equivalent to $13,160 in 2015),[32] and also forbade him from traveling to Dodger Stadium for the final, crucial two-game series of the season.[27] Roseboro filed a $110,000 damage suit against Marichal one week after the incident but, eventually settled out of court for $7,500.[27]

Many people protested the apparently light punishment meted out, since it would cost Marichal only two starts.[27] The Giants were in a tight pennant race with the Dodgers (as well as the Pirates, Reds, and Braves) and the race was decided with only two games to play. The Giants, who ended up winning the August 22 game and were down only 1⁄2 game afterward, eventually lost the pennant to the Dodgers by 2 games. Ironically, the Giants went on a 14-game win streak that started during Marichal's absence and by then it was a two-team race as the Pirates, Reds, and Braves fell further behind. But then the Dodgers won 15 of their final 16 games (after Marichal had returned) to win the pennant. Marichal won in his first game back, 2–1 vs. the Astros on September 9 (the same day Koufax pitched his perfect game vs. the Cubs), but lost his last three decisions as the Giants slumped in the season's final week.

Marichal didn't face the Dodgers again until spring training in April 3, 1966. In his first at bat against Marichal since the incident, Roseboro hit a three-run home run.[33] San Francisco General Manager Chub Feeney approached Dodgers General Manager Buzzy Bavasi to attempt to arrange a handshake between Marichal and Roseboro however, Roseboro declined the offer.[33]

Years later, Roseboro stated that he was retaliating for Marichal having thrown at Wills.[27] He explained that Koufax would not throw at batters for fear of hurting them due to the velocity of his pitches.[27] He further stated that his throwing close to Marichal's ear was, "standard operating procedure", as a form of retribution.[27] After years of bitterness, Roseboro and Marichal became close friends in the 1980s, getting together occasionally at Old-Timers games, golf tournaments and charity events.[27]

1970–75

In 1970, Marichal experienced a severe reaction to penicillin which led to back pain and chronic arthritis. Marichal's career stumbled in 1970, when he only posted 12 wins and his ERA shot up to 4.12, before straightening itself out with a stellar 1971 season in which he won 18 games and his ERA dropped below 3.00.[1] It was the only season in which Marichal earned any consideration for the Cy Young Award, finishing in 8th place. It was his final great season (and his final of nine All-Star appearances), however, as he posted 6–16 and 11–15 records in 1972 and 1973 respectively.[1]

After the 1973 season, the Giants sold Marichal to the Boston Red Sox.[34] He had a fairly solid 1974, going 5–1 in 11 starts, but was released after the season.[1] He then signed with the Dodgers as a free agent.[34] Dodger fans had never forgiven Marichal for his attack on Roseboro 10 years earlier, and it took a personal appeal from Roseboro to calm them down. However, Marichal's 1975 didn't last long; he was lit up for nine runs, 11 hits and a 13.50 ERA in only two starts before retiring.[35] He finished his career with 243 victories, 142 losses, 244 complete games, 2,303 strikeouts and a 2.89 ERA over 3,507 innings pitched.[1] He played in the 1962 World Series against the New York Yankees (one start, a no decision) and the 1971 National League Championship Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates (losing his only start).[36] Between 1962 and 1971, the Giants averaged 90 wins a season, and Marichal averaged 20 wins a year.

No-hitter and All-Star performances

Marichal pitched a no-hitter on June 15, 1963, and was named to nine All-Star teams.[1][37] He was selected the Most Valuable Player of the 1965 game in Minneapolis, in which he pitched three shutout innings and faced the minimum nine batters, giving up one hit. His overall All-Star Game record was 2–0 with a 0.50 ERA in eight appearances facing 62 batters in 18 total innings, second-most in innings pitched only to Don Drysdale (19.1 innings; 2-1, 1.40 ERA and 69 batters faced).[20]

Honors

| |

| Juan Marichal's number 27 was retired by the San Francisco Giants in 1975. |

Marichal was passed over for election to the Baseball Hall of Fame during his first two years of eligibility, by all accounts because the Baseball Writers' Association of America voters still held his attack on Roseboro against him. However, after a personal appeal by Roseboro, Marichal was elected in 1983, and thanked Roseboro in his induction speech.[30][35] When Roseboro died in 2002, Marichal served as an honorary pallbearer at his funeral and told the gathered, "Johnny's forgiving me was one of the best things that happened in my life. I wish I could have had John Roseboro as my catcher."[38]

Marichal's uniform number 27 has been retired by the Giants.[39] In 1990, Marichal, who was working as a broadcaster for Spanish radio, was on hand to see his son-in-law at the time, José Rijo, win the World Series Most Valuable Player Award. In 1999, he ranked #71 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and was a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[40][41] He was honored before a game between the Giants and Oakland Athletics with a statue outside AT&T Park in 2005, and was named one of the three starting pitchers on Major League Baseball's Latino Legends Team. In 1976, sportswriter Harry Stein published an "All Time All-Star Argument Starter", consisting of five ethnic baseball teams. Marichal was the right-handed pitcher on Stein's Latin team. The Giants also honored him by wearing jerseys that said "Gigantes." Marichal was inducted into the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame on July 20, 2003 in pregame on field ceremony at Pac Bell Park.[42] In 2015 the Estadio Quisqueya in his home country was renamed Quisqueya stadium Juan Marichal after him.[43][44]

Controversy

In 2008, Marichal was filmed at a cockfight in the Dominican Republic along with New York Mets pitcher Pedro Martínez. The incident caused controversy in the United States, but Martinez defended their attendance at the cockfight by saying "I understand that people are upset, but that is part of our Dominican culture and is legal in the Dominican Republic". He added "I was invited by my idol, Juan Marichal, to attend the event as a spectator, not as a participant."[45]

Pronunciation

The popular media tended to pronounce his surname "MARE-i-shall". West coast broadcasters tended to pronounce his name more like proper Spanish enunciation, "mahr-ee-CHAHL".

See also

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Juan Marichal at Baseball Reference

- ↑ http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2004/aug/23/20040823-011141-7243r/?page=all

- 1 2 3 Juan Marichal: He Was Winningest Pitcher of '60s, by John Lowe, Baseball Digest, August 1998, Vol. 57, No. 8, ISSN 0005-609X

- ↑ Juan Marichal-A Man In Many Shadows, by Michael R. Lauletta, Baseball Digest, June 1970, Vol. 29, No. 6, ISSN 0005-609X

- ↑ Juan Marichal at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- 1 2 Marichal, Freedman, 2011. p. 13

- 1 2 Marichal, Freedman, 2011. p. 14

- ↑ Marichal, Freeman, 2011. p. 20

- 1 2 Marichal, Freeman, 2011. p. 21

- 1 2 3 Marichal, Freedman, 2011. p. 15

- 1 2 3 Marichal, Freedman, 2011. p. 16

- 1 2 Marichal, Freedman, 2011. p. 17

- ↑ Marichal, Freedman, 2011. p. 23

- ↑ "The Dandy Dominican", Time magazine, June 10, 1966

- ↑ Baseball Digest, June 1990, Vol. 49, No. 6, ISSN 0005-609X

- ↑ July 19, 1960 Phillies-Giants box score at Baseball Reference

- ↑ 1963 National League Pitching Leaders at Baseball Reference

- ↑ 1968 National League Pitching Leaders at Baseball Reference

- 1 2 1969 National League Pitching Leaders at Baseball Reference

- 1 2 Haft, Chris. Marichal returns to city of All-Star MVP performance, retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ 1965 National League Pitching Leaders at Baseball Reference

- ↑ July 2, 1963, by Ron Fimrite, Sports Illustrated, July 19, 1993

- 1 2 3 4 5 July 2, 1963 Braves-Giants box score at Baseball Reference

- ↑ Marichal-Spahn epic duel was 50 years ago, San Jose Mercury News

- 1 2 Goldstein, Richard (August 20, 2002). "John Roseboro, a Dodgers Star, Dies at 69". New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mann, Jack (August 30, 1965). "The Battle Of San Francisco". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Marichal clubbing of Roseboro an ugly side of baseball". The Times-News. Associated Press. 22 August 1990. p. 18. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rosengren, John (2014). "Marichal, Roseboro and the inside story of baseball's nastiest brawl". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ↑ "August 22, 1965 Dodgers-Giants box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Put up your dukes". espn.go.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ "MLBN Remembers ("Incident at Candlestick")". MLBN-tv. November 17, 2011.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- 1 2 "John Roseboro Hammers Homer In First Meeting With Juan Marichal". The Day. Associated Press. 4 April 1966. p. 25. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- 1 2 Juan Marichal Trades and Transactions at Baseball Almanac

- 1 2 Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ↑ Juan Marichal postseason pitching statistics at Baseball Reference

- ↑ June 15, 1963 Colt 45s-Giants box score at Baseball Reference

- ↑ Plaschke, Bill (22 August 2015). "Fifty years after Giants' Juan Marichal hit Dodgers' John Roseboro with a bat, all is forgiven".

- ↑ Giants retired numbers at MLB.com

- ↑ Juan Marichal at The Sporting News 100 Greatest Baseball Players

- ↑ Juan Marichal at The Major League Baseball All-Century Team

- ↑ "Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum". Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ "Senado reconocerá a Pedro Martínez ; entregan gaceta con ley 11-15 a Juan Marichal". El Nacional (in Spanish). 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ Terrero Galarza, Satosky (2016-02-01). "Nombre y silueta de Juan Marichal ya adornan el estadio Quisqueya". El Caribe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ "Video showed Pedro, Marichal at cockfight" ESPN

Bibliography

- Marichal, Juan and Freedman, Lew (2011). Juan Marichal: My Journey from the Dominican Republic to Cooperstown. MVP Books. ISBN 978-0760340592.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Juan Marichal. |

- Juan Marichal at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Baseball Library

- Retrosheet

- Baseball Hall of Fame: Marichal Tops Cooperstown's Cy-Less List

- SABR BioProject

| Preceded by Don Nottebart |

No-hitter pitcher June 15, 1963 |

Succeeded by Ken Johnson |

| Preceded by Willie Mays |

Major League Player of the Month May, 1966 |

Succeeded by Gaylord Perry |