Joseph Howe

| The Honourable Joseph Howe | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia | |

|

In office May 1, 1873 – June 1, 1873 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor General | The Earl of Dufferin |

| Premier | William Annand |

| Preceded by | Charles Hastings Doyle |

| Succeeded by | Adams George Archibald |

| 5th Premier of Nova Scotia | |

|

In office August 3, 1860 – June 6, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | William Young |

| Succeeded by | James W. Johnston |

| MP for Hants | |

|

In office 1867–1873 | |

| Preceded by | none |

| Succeeded by | Monson Henry Goudge |

| MLA for Halifax County | |

|

In office 1836 – February 24, 1851 | |

| MLA for Cumberland County | |

|

In office 1851–1855 | |

| Preceded by | none |

| Speaker of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly | |

|

In office 1840–1843 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel George William Archibald |

| Succeeded by | William Young |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

December 13, 1804 Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Died |

June 1, 1873 (aged 68) Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Political party | Reformer |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine Susan Ann McNab (1806–1890) |

| Signature |

|

Joseph Howe, PC (December 13, 1804 – June 1, 1873) was a Nova Scotian journalist, politician, public servant, and poet. Howe is often ranked as one of Nova Scotia's most admired politicians and his considerable skills as a journalist and writer have made him a provincial legend.[1]

He was born the son of John Howe and Mary Edes at Halifax and inherited from his loyalist father an undying love for Great Britain and her Empire.[2] At age 23, the self-taught but widely read Howe purchased the Novascotian, soon making it into a popular and influential newspaper. He reported extensively on debates in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and travelled to every part of the province writing about its geography and people.[1] In 1835, Howe was charged with seditious libel, a serious criminal offence, after the Novascotian published a letter attacking Halifax politicians and police for pocketing public money. Howe addressed the jury for more than six hours, citing example after example of civic corruption. The judge called for Howe's conviction, but swayed by his passionate address, jurors acquitted him in what is considered a landmark case in the struggle for a free press in Canada.[3]

The next year, Howe was elected to the assembly as a liberal reformer, beginning a long and eventful public career. He was instrumental in helping Nova Scotia become the first British colony to win responsible government in 1848. He served as premier of Nova Scotia from 1860 to 1863 and led the unsuccessful fight against Canadian Confederation from 1866 to 1868. Having failed to persuade the British to repeal Confederation, Howe joined the federal cabinet of John A. Macdonald in 1869 and played a major role in bringing Manitoba into the union. Howe became the third Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia in 1873, but died after only three weeks in office.

Early life

The Howe family was of Puritan stock from Massachusetts. Having remained loyal to the crown during the American Revolution, the family of John Howe joined the flood of United Empire Loyalists out of the United States after the American revolutionaries succeeded in their claims of independence. Howe arrived at Halifax in 1779 and set up a printing shop, where he published the first issue of the Halifax Journal in December 1780. In 1801, Howe was rewarded for his loyalty by appointment as the King's Printer and in 1803 he became deputy postmaster for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. In 1798, he had married Mary Edes; their son Joseph was born at Halifax on December 13, 1804. Like many lads of that time, Joseph Howe attended the Royal Acadian School before beginning an apprenticeship, which he served at his father's printing shop starting at the age of 23. He married Catherine Ann Susan McNab on February 2, 1828.

That same year he went into the printing business himself with the purchase of the Nova Scotian, a Halifax newspaper. Howe acted as its editor until 1841, turning the paper into the most influential in the province. Not only did he personally report the legislative assembly debates in its columns, he also published provincial literature and his own travel writings, using the paper as a means for educating the people of Nova Scotia, and himself. "His name ranks as perhaps the greatest in Canadian journalism."[4]

Libel trial

On January 1, 1835, Howe's Novascotian published an anonymous letter accusing Halifax politicians and police of pocketing £30,000 over a thirty-year period. The outraged civic politicians had Howe charged with seditious libel, a serious criminal offence. Howe's case seemed hopeless since truth was not a defence. The prosecution had only to prove that Howe had published the letter. Howe decided to act as his own lawyer. For more than six hours, he addressed the jury, citing case after case of civic corruption. He spoke eloquently about the importance of press freedom, urging jurors "to leave an unshackled press as a legacy to your children." Even though the judge instructed the jury to find Howe guilty, jurors took only 10 minutes to acquit him. The decision was a landmark event in the slow evolution of press freedom in Canada.[5]

Political career

.png)

Eventually, Howe decided to run for office in order to effect the changes he championed in his newspaper. He was first elected in 1836, campaigning on a platform of support for responsible government. Howe initially proposed only an elected legislative council but he was quick to agree with the concept of a fully representative government. He was suspicious of formal political parties feeling that they were too restrictive. It was, however, largely his doing that members favouring Liberal principles were able to dominate assembly from 1836 to 1840. He formed a coalition with Conservative leader James William Johnston in 1840 hoping to further the cause of responsible government. His writings in the Novascotian at that time so enraged John C. Halliburton (son of the judge Brenton Halliburton in Howe's libel trial) that Haliburton called Howe out for a duel. The duel took place on March 14, 1840, at Point Pleasant. When Haliburton missed with his shot, Howe "deloped" deliberately missing by firing his gun in the air.[6] Howe held the office of Speaker of the assembly in 1841 and collector of excise for Halifax in 1842.

The coalition collapsed under various political conflicts, leading to Howe's resignation from the Council in 1843. The promotion of political ideas in his newspapers were rewarded with a seven-seat Liberal majority in the 1847 election. This led to the formation of the first responsible government in Canada in January 1848. While James Uniacke was officially the Premier, many regarded it as Joseph Howe's ministry. Howe assumed the post of Provincial Secretary, adapting existing institutions to the new system of government. He also began a campaign of railway construction, resigning as Provincial Secretary in 1853 to become Nova Scotia's first Chief Commissioner of Railways; as Commissioner he oversaw the initial construction of the Nova Scotia Railway. In addition, Howe was involved with recruiting American troops for the Crimean War. These activities left him with little time to campaign in the 1855 general election which he lost to Charles Tupper in Cumberland. This election also led to conflict with Catholic members of the Liberal party because Howe had ridiculed their religious doctrine. This resulted in a Liberal defeat in 1856. The Liberals did not return to power until 1860 at which time Howe became provincial secretary. When the Premier, William Young, was appointed as a judge later that year, Joseph Howe assumed the leadership of the party and therefore became Premier. He served as Premier until 1863 when he accepted the position of Imperial Fisheries Commissioner.

Confederation debate

Howe's fisheries duties prevented his attendance at the Charlottetown Conference. By the time he returned to Nova Scotia in November 1864, the Quebec Conference had taken place, and the Quebec Resolutions widely disseminated. He had no chance to influence their content. He led Nova Scotia's anti-Confederation movement believing the Quebec Resolutions to be bad for the province. Because he was still linked with the imperial fishery he expressed his initial opposition anonymously through the Botheration Letters, a series of 12 editorials that appeared in the Morning Chronicle between January and March 1865. This was the extent of his participation in the union debate until March 1866. He learned that Charles Tupper planned to force the Confederation Resolution through the legislature. When he failed to prevent passage of the resolution Howe began a vigorous campaign for repeal by delegations to London and then publishing a variety of anti-Confederation papers and pamphlets. This strategy failed to prevent the Imperial Parliament enacting the British North America Act in 1867. Nova Scotians elected 18 out of 19 anti-Confederation candidates as members of the first Dominion Parliament. Joseph Howe led the anti-Confederates in the Canadian House of Commons where he made a speech about his opposition to confederation.

Having failed to win repeal of Confederation in 1868 Howe recognized the futility of further protests. He refused to contemplate secession from the Canadian Confederation nor American annexation because of his loyalty to Britain. He ran in the great Hants County byelection of 1869 to create better terms for Nova Scotia within Canada rather than continue to seek repeal of Confederation. The Great Hants Campaign of 1869 was very difficult and compromised Howe's physical health. Many Nova Scotians continued to support the anti-confederation efforts but the Hants County electorate continued to support Joseph Howe.

In 1869 Howe joined the Canadian Cabinet as President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada after receiving a promise of "better terms" for Nova Scotia. In November 1869, he became secretary of state for the provinces in which post he played a role in Manitoba's entry into Confederation. He resigned his Cabinet post to become the 3rd Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia post Confederation in 1873. He died in office only a few weeks after his appointment. He is buried in Camp Hill Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Railway promotion

In 1854, he resigned as the provincial secretary in order to head a bi-partisan railway commission. He never completed the whole project but did however, succeed in completing lines from Halifax to Windsor and Truro.

Poetry

Howe created a substantial body of poetry, much of it related to his appreciation of Nova Scotia and its history.[7] While he had published some poems during his life and had been preparing others for publication, it was not until a year after his death that his family made them public through the publishing of Poems and Essays.[8][9]

Family

Joseph Howe married Catherine Susan Ann McNab, daughter of Captain John McNab, Nova Scotia Regiment of Fencible Infantry,[10] on February 2, 1828. She was born in 1808 in the barracks at the entrance to the harbour of St. John's, Newfoundland, where her father was in command of the troops. She lived with her father on McNab's Island, which had previously been occupied by her uncle, Peter McNab. In Joseph Howe's "Poems and Essays" (Montreal: 1874), there are two poems addressed to his wife. Towards the close of her life, the Legislature of Nova Scotia granted her a small pension. She died in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, July 6, 1890, and is buried alongside her husband in Camp Hill Cemetery, Halifax. The couple`s son, Sydenham Howe, lived in Middleton, Nova Scotia.[11] Howe also had a son by another woman, both of whom lived in a home Howe maintained in Maitland, Nova Scotia.[12]

Legacy

- Joseph Howe Drive, Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Joseph Howe Building, Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Joseph Howe School, Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Joseph Howe Falls, Victoria Park, Truro

- Joseph Howe Park, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

- Joseph Howe Senior Public School, Scarborough (Toronto), Ontario

- The 100th anniversary of Howe's death was commemorated with the issue of an 8-cent stamp by Canada Post.[13]

- From 1973 until 1985 a Joseph Howe Festival was held in Halifax and in other places in Nova Scotia.[14]

Media

- The Night They Killed Joe Howe (1960) (TV drama), starring Douglas Rain, Austin Willis (as William Annand) and Star Trek's James Doohan[15]

- Apr 26, 1961: The place of Joseph Howe in Canadian history (TV drama). James Barron plays Howe[16]

- Nov 7, 1956: "The Case of Posterity versus Joseph Howe," (CBC Folio) a dramatic argument by Joseph Schull [17]

- Joseph Howe: The Tribune of Nova Scotia (1961 short film)

- Joseph Howe - Heroes of Hants County Series by Shawn Scott on YouTube

Gallery

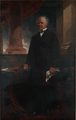

Joseph Howe By William Notman

Joseph Howe By William Notman Joseph Howe by Henry Sandham, Province House (Nova Scotia), from photo by Notman

Joseph Howe by Henry Sandham, Province House (Nova Scotia), from photo by Notman

See also

- C. D. Howe, 20th century politician and distant relative born in the United States

- The Novascotian

- Nova Scotia Heritage Day

- History of Nova Scotia

Notes

- 1 2 Beck, J. Murray (1972). "Howe, Joseph". In Hayne, David. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. X (1871–1880) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Beck, J. Murray. (1982) Joseph Howe: Conservative Reformer 1804–1848. (v.1). Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Kesterton, W.H. (1967) A History of Journalism in Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Hopkins, J. Castell (1898). An historical sketch of Canadian literature and journalism. Toronto: Lincott. p. 223. ISBN 0665080484.

- ↑ Kesterton, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ "Joseph Howe: Tribune of Nova Scotia". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "At the sign of the hand and pen; Nova Scotian authors".

- ↑ "Howe, Joseph - Representative Poetry Online".

- ↑ "Biography – HOWE, JOSEPH – Volume X (1871-1880) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography".

- ↑ Piers, Harry; "The Fortieth Regiment, Raised at Annapolis Royal in 1717; and Five Regiments Subsequently Raised in Nova Scotia"; Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, vol. XXI, Halifax, NS, 1927, p 175

- ↑ Morgan, Henry James Types of Canadian women and of women who are or have been connected with Canada : (Toronto, 1903)

- ↑ "The Enfield Weekly Press. September 27, 2011".

- ↑ philcovex. "Postal History Corner". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Coins and Canada. "Coins and Canada - Halifax - Joseph Howe Festival - Trade dollars and municipal tokens". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Film Review

- ↑ "Episode Guide for Explorations".

- ↑ "Episode Guide for Folio".

References

- Beck, J. Murray. (1982) Joseph Howe: Conservative Reformer 1804–1848. (v.1). Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-0387-0

- Beck, J. Murray. (1983) Joseph Howe: The Briton Becomes Canadian 1848–1873. (v.2). Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-0388-9

- John Roulston Saul - Joseph Howe

- William Lawson. The Tribune of Nova Scotia

Daniel N. Paul, We Were Not the Savages, pp 205–218. (2006), Fernwood Publishing, Halifax, N.S. ISBN 1-55266-209-8

External links

- Works by or about Joseph Howe at Internet Archive

- Works by Joseph Howe at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Beck, J. Murray (1972). "Howe, Joseph". In Hayne, David. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. X (1871–1880) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Joseph Howe – Parliament of Canada biography

- "The Indictment for Libel and Howe's Defense".

- "Sydenham Howe's Scrapbook: Joseph Howe and His World". novascotia.ca. Nova Scotia Archives. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Poems and essays by Joseph Howe