John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury

| The Earl of Shrewsbury | |

|---|---|

|

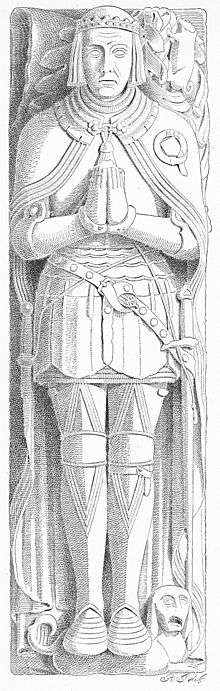

Effigy of John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, KG (d.1453), Whitchurch, Shropshire. A talbot dog is shown as the crest (head missing) on his helmet on which his head rests and also as his footrest | |

| Lord Lieutenant of Ireland | |

|

In office 1414–1419 | |

| Monarch |

Henry IV Henry V |

| Preceded by | Sir John Stanley |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Ormond |

| Lord High Steward of Ireland | |

|

In office 1446–1453 | |

| Monarch | Henry VI |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | The 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury |

| Constable of France | |

|

In office 1445–1453 | |

| Monarch | Henry VI |

| Preceded by | The Duke of Brittany |

| Succeeded by | The Count of Saint-Pol |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1384 or 1387 Blakemere, Shropshire |

| Died |

17 July 1453 Castillon-la-Bataille, Gascony |

| Cause of death | Killed in Action |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | English army |

| Battles/wars |

Hundred Years' War Siege of Orléans Battle of Patay (POW) Battle of Castillon † |

John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury and 1st Earl of Waterford KG (1384/1387 – 17 July 1453), known as "Old Talbot", was a noted English military commander during the Hundred Years' War, as well as the only Lancastrian Constable of France.

Origins

He was descended from Richard Talbot, a tenant in 1086 of Walter Giffard at Woburn and Battledsen in Bedfordshire. The Talbot family were vassals of the Giffards in Normandy.[1] Hugh Talbot, probably Richard's son, made a grant to Beaubec Abbey, confirmed by his son Richard Talbot in 1153. This Richard (d. 1175) is listed in 1166 as holding three fees of the Honour of Giffard in Buckinghamshire. He also held a fee at Linton in Herefordshire, for which his son Gilbert Talbot (d. 1231) obtained a fresh charter in 1190.[2] Gilbert's grandson Gilbert (d. 1274) married Gwenlynn Mechyll, daughter and sole heiress of the Welsh Prince Rhys Mechyll, whose armorials the Talbots thenceforth assumed in lieu of their own former arms. Their son Sir Richard Talbot, who signed the Barons' Letter, 1301, held the manor of Eccleswall in Herefordshire in right of his wife Sarah, sister of William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick. In 1331 Richard's son Gilbert Talbot (1276–1346) was summoned to Parliament, which is considered evidence of his baronial status – see Baron Talbot.[3] Gilbert's son Richard married Elizabeth Comyn, bringing with her the inheritance of Goodrich Castle.

John Talbot was born in 1383 at Black Mere Castle[4] near Whitchurch, Shropshire, as second son of Richard Talbot, 4th Baron Talbot, by Ankaret le Strange, 7th Baroness Strange of Blackmere. His younger brother Richard became Archbishop of Dublin and Lord Chancellor of Ireland : he was one of the most influential Irish statesmen of his time, and his brother's most loyal supporter during his often troubled years in Ireland. Their birthplace is now a scheduled monument listed as Blakemere Moat, site of the demolished fortified manor house.[4]

His father died in 1396 when Talbot was just nine years old, and so it was Ankaret's second husband, Thomas Neville, Lord Furnival, who became the major influence in his early life. The marriage also gave the opportunity of a title for her second son as Neville had no sons with the title going through his eldest daughter Maud,[5] who would become John's first wife.

First marriage

Talbot was married before 12 March 1407 to Maud Neville, 6th Baroness Furnivall, daughter and heiress of Thomas Neville, 5th Baron Furnivall, the son of John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby. He was summoned to Parliament in her right from 1409.

The couple are thought to have five children:

- Thomas Talbot (19 June 1416 Finglas, Ireland – 10 August 1416)

- John Talbot, 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury (c. 1417 – 11 July 1460)

- Sir Christopher Talbot (1419–10 August 1443),

- Lady Joan Talbot (c 1422), married James Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley.

- Ann Bottreaux (Talbot) married John Bottreaux, of Abbot's Salford

In 1421 by the death of his niece he acquired the Baronies of Talbot and Strange. His first wife, Maud died on 31 May 1422. It has been suggested that she died as an indirect result of giving birth to her daughter Joan, although due to a lack of evidence about her before marriage to Lord Berkeley, there is even a theory that she was actually Talbot's daughter-in-law through marriage to Sir Christopher Talbot.

Second marriage

On 6 September 1425, he married Lady Margaret Beauchamp, eldest daughter of Richard de Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick and Elizabeth de Berkeley in the chapel at Warwick Castle. They had five children:

- John Talbot, 1st Viscount Lisle (1426 – 17 July 1453)

- Sir Louis Talbot (c 1429-1458)

- Sir Humphrey Talbot (before 1434 – c. 1492)

- Lady Eleanor Talbot (c February/March 1436 – 30 June 1468) married to Sir Thomas Butler and mistress to King Edward IV.

- Lady Elizabeth Talbot (c December 1442/January 1443). She married John de Mowbray, 4th Duke of Norfolk.

Talbot is known to have had at least one illegitimate child, Henry. He may have served in France with his father as it is known that a bastard son of the Earl of Shrewsbury was captured by the Dauphin on 14 August 1443.[6]

Early career

From 1404 to 1413 he served with his elder brother Gilbert in the Welsh revolt or the rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr. Then for five years from February 1414 he was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, where he did some fighting. He had a dispute with the Earl of Ormond and Reginald Grey, 3rd Baron Grey de Ruthyn over the inheritance for the honour of Wexford which he held.[7] Complaints were made against him both for harsh government in Ireland and for violence in Herefordshire, where he was a friend of the Lollard Sir John Oldcastle, and for land disputes with retainers of the Earl of Arundel.[8]

The dispute with the Earl of Ormond escalated into a long-running feud between Shrewsbury and his brother, the Archbishop of Dublin, on the one hand and the Butler family and their allies the Berkeleys on the other. The feud reached its height in the 1440s, and in the end just about every senior official in Ireland had taken sides in the quarrel; both sides were reprimanded by the Privy Council for weakening English rule in Ireland. Friendly relations were finally achieved by the marriage of Shrewsbury's son and heir to Ormond's daughter, Lady Elizabeth Butler.[9]

From 1420 to 1424 he served in France, apart from a brief return at the end of the first year to organise the festivities of celebrating the coronation of Catherine of France, the bride of Henry V.[10]

He returned to France in May 1421 and took part in the Battle of Verneuil on 17 August 1424 earning him the Order of the Garter.

In 1425, he was lieutenant again for a short time in Ireland;[8] he served again in 1446-7.

Service in France

So far his career was that of a turbulent Marcher Lord, employed in posts where a rough hand was useful. In 1427 he went again to France,[8] where he fought alongside the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Warwick with distinction in Maine and at the Siege of Orléans. He fought at the Battle of Patay on 18 June 1429 where he was captured and held prisoner for four years.

He was released in exchange for the French leader Jean Poton de Xaintrailles and returned to England in May 1433. He stayed until July when he returned to France under the Earl of Somerset.[11]

Talbot was a daring and aggressive soldier, perhaps the most audacious captain of the age. He and his forces were ever ready to retake a town and to meet a French advance. His trademark was rapid aggressive attacks. He was rewarded by being appointed governor and lieutenant general in France and Normandy and, in 1434, the Duke of Bedford made him Count of Clermont. He also reorganized the army with captains and lieutenants, trained the men for sieges, and equipped them accordingly. But when the Duke of Bedford died in 1435, the Burgundian government in Paris defected to the French, leaving Talbot, known as le roi talbot as the main English general in the field.[12][13]

In January 1436, he led a small force including Thomas Kyriell and routed La Hire and Xaintrailles at Ry near Rouen. The following year at Crotoy, after a daring passage of the Somme, he put a numerous Burgundian force to flight. In December 1439, following a surprise flank attack on their camp, he dispersed the 6000 strong army of the Constable Richemont, and the following year he retook Harfleur. In 1441, he pursued the French army four times over the Seine and Oise rivers in an unavailing attempt to bring it to battle.

Lord Shrewsbury

Around February 1442, Talbot returned to England to request urgent reinforcements for the Duke of York in Normandy. In March, under king's orders, ships were requisitioned for this purpose with Talbot himself responsible for assembling ships from the Port of London and from Sandwich.[14]

On Whit Sunday, 20 May, Henry VI created him Earl of Shrewsbury. Just five days later, with the requested reinforcements, Talbot returned to France where in June they mustered at Harfleur. During that time, he met his six-old year daughter Eleanor for the first time and almost certainly left the newly created Countess Margaret pregnant with another child.[15]

In June 1443, Talbot again returned to England on behalf of the Duke of York to plead for reinforcements, but this time the English Council refused, instead sending a separate force under Shrewsbury's brother-in-law, Edmund Beaufort. His son, Sir Christopher stayed in England where shortly afterwards he was murdered with a lance at the age of 23 by one of his own men, Griffin Vachan of Treflidian on 10 August at "Cawce, County Salop" (Caus Castle).[16]

The English Achilles

He was appointed in 1445 by Henry VI (as king of France) as Constable of France. Taken hostage at Rouen in 1449 he promised never to wear armour against the French King again, and he was true to his word. However, though he did not personally fight, he continued to command English forces against the French. In England he was widely renowned as the best general King Henry VI had. The king relied upon his support at Dartford in 1452, and in 1450 to suppress Cade's Revolt. In 1452 he was ordered to Bordeaux to save the duchy of Aquitaine. He repaired castle garrisons facing mounting pressure from France, when some reinforcements arrived with his son John, Viscount Lisle in spring 1453.

He was defeated and killed in July 1453 at the Battle of Castillon near Bordeaux, which effectively ended English rule in the duchy of Aquitaine, a principal cause of the Hundred Years' War. His heart was buried in the doorway of St Alkmund's Church, Whitchurch, Shropshire.[17]

The victorious French generals raised a monument to Talbot on the field called Notre Dame de Talbot and a French Chronicler paid him handsome tribute:

"Such was the end of this famous and renowned English leader who for so long had been one of the most formidable thorns in the side of the French, who regarded him with terror and dismay" – Matthew d'Escourcy

Although Talbot is generally remembered as a great soldier, some have raised doubts as to his generalship. In particular, charges of rashness have been raised against him. Speed and aggression were key elements in granting success in medieval war, and Talbot's numerical inferiority necessitated surprise. Furthermore, he was often in the position of trying to force battle on unwilling opponents. At his defeat at Patay in 1429 he was advised not to fight there by Sir John Fastolf, who was subsequently blamed for the debacle, but the French, inspired by Joan of Arc, showed unprecedented fighting spirit – usually they approached an English position with trepidation. The charge of rashness is perhaps more justifiable at Castillon where Talbot, misled by false reports of a French retreat, attacked their entrenched camp frontally – facing wheel to wheel artillery.

Cultural influence

He is portrayed heroically in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 1: "Valiant Lord Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, Created, for his rare success in arms". Talbot's failures are all blamed on Fastolf and feuding factions in the English court. Thomas Nashe, commenting on the play in his booklet Pierce Penniless, stated that Talbot's example was inspiring Englishmen anew, two centuries after his death,

How would it have joyed brave Talbot, the terror of the French, to think that after he had lain two hundred years in his tomb, he should triumph again on the stage, and have his bones new embalmed with the tears of ten thousand spectators at least (at several times) who in the tragedian that represents his person imagine they behold him fresh bleeding. I will defend it against any collian or clubfisted usurer of them all, there is no immortality can be given a man on earth like unto plays.

Fiction

John Talbot is shown as a featured character in Koei's video game Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War, appearing as the left-arm of Edward, the Black Prince, in which he assists the former and the respective flag of England throughout his many portrayals.

Talbot appears as one of the primary antagonists in the PSP game Jeanne d'Arc.

See also

References

- ↑ Domesday Book: a complete translation (2002), p. 568; K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, Domesday People, vol. 1: Domesday Book (1999), p. 368.

- ↑ K. S. B. Keats-Rohan, Domesday People, vol. 2: Domesday Descendants (2002), p. 1123.

- ↑ G. E. Cokayne; with Vicary Gibbs, H. A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed., 13 volumes in 14 (1910–1959), volume XII/1, p. 610.

- 1 2 Blakemere Moat

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, Eleanor The Secret Queen, Page 14, The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, Eleanor The Secret Queen, Page 35 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, Eleanor The Secret Queen, Page 16 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- 1 2 3

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (1911). "Shrewsbury, John Talbot, 1st Earl of". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1017–1018.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (1911). "Shrewsbury, John Talbot, 1st Earl of". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1017–1018. - ↑ Otway-Ruthven, A.J. History of Mediaeval Ireland Barnes and Noble, 1993

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, "Eleanor The Secret Queen", Page 15 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, Eleanor The Secret Queen, Page 17 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- ↑ Talbot, Rev Hugh,

- ↑ A J Pollard

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, Eleanor The Secret Queen, Page 26 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- ↑ John Ashdown-Hill, Eleanor The Secret Queen, Page 29 The History Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1441-1446, pp 397-398; p220

- ↑ "Whitchurch". Shropshire Tourism. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

Sources

- Allmand, C T (1983) Lancastrian Normandy, 1415–1450: The History of a Medieval Occupation. New York: Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, Pp. xiii, 349

- Barker, J. (2000) The Hundred Years' War

- Bradbury, M. (1983) Medieval Archery

- Mortimer, I. (2008), 1415: A Year of Glory

- Pollard, A.J. (1983) John Talbot and the War in France, 1427-1453, Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press, Inc

- Sumption, J. (2004) The Hundred Years' War: Trial by Fire vol. 2 of 2

- Talbot, Rev H., (1980) The English Achilles: the life of John Talbot

Journals

- Speculum / Volume 60 / Issue 04 / October 1985, pp 939–941

Ancestry

| Ancestors of John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New office | Lord High Steward of Ireland 1446–1453 |

Succeeded by The 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury |

| Peerage of England | ||

| New creation | Earl of Shrewsbury 1442–1453 |

Succeeded by John Talbot |

| Preceded by Ankaret Talbot |

Baron Strange of Blackmere 1421–1453 | |

| Baron Talbot 1421–1453 | ||

| Preceded by Thomas Neville |

Baron Furnivall (jure uxoris (primae)) 1407–1422 | |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| New creation | Earl of Waterford 1446–1453 |

Succeeded by John Talbot |