John Easton

| John Easton | |

|---|---|

| 15th Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

|

In office 1690–1695 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Bull |

| Succeeded by | Caleb Carr |

| 8th Deputy Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

|

In office 1674–1676 | |

| Governor | William Coddington |

| Preceded by | William Coddington |

| Succeeded by | John Cranston |

| 3rd, 5th, 7th and 10th Attorney General of Rhode Island | |

|

In office May 1656 – May 1657 | |

| Governor | Roger Williams |

| Preceded by | John Cranston |

| Succeeded by | John Greene |

|

In office May 1660 – May 1663 | |

| Governor |

William Brenton Benedict Arnold |

| Preceded by | John Greene |

| Succeeded by | John Sanford |

|

In office 1664–1670 | |

| Governor |

Benedict Arnold William Brenton Benedict Arnold |

| Preceded by | John Sanford |

| Succeeded by | John Sanford |

|

In office 1672–1674 | |

| Governor | Nicholas Easton |

| Preceded by | Joseph Torrey |

| Succeeded by | Peter Easton |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

baptized 19 December 1624 Romsey, Hampshire, England |

| Died |

12 December 1705 Newport, Rhode Island |

| Resting place | Coddington Cemetery, Newport |

| Spouse(s) | Mehitable Gaunt |

| Occupation | Deputy Governor, Governor |

| Religion | Quaker |

John Easton (1624–1705) was a political leader in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, devoting decades to public service before eventually becoming governor of the colony. Born in Hampshire, England, he sailed to New England with his widowed father and older brother, settling in Ipswich and Newbury in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. As a supporter of the dissident ministers John Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Controversy, his father was exiled, and settled in Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island (later called Rhode Island) with many other Hutchinson supporters. Here there was discord among the leaders of the settlement, and his father followed William Coddington to the south end of the island where they established the town of Newport. The younger Easton remained in Newport the remainder of his life, where he became involved in civil affairs before the age of 30.

Ultimately serving more than four decades in the public service of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Easton began as an Attorney General for the island towns of Portsmouth and Newport, soon fulfilling the same role for the entire colony. To this line of service he added positions as Commissioner, Deputy, and Assistant, for many years serving simultaneously in multiple roles. In 1674 he was elected to the office of deputy governor, serving for two years, with a part of his tenure being during King Philip's War, about which he published a written treatise. Following the overthrow of the Edmund Andros governorship under the Dominion of New England, Easton was elected as governor of the colony for five consecutive years. While in office his biggest concerns were funding the ongoing war that England was fighting with France, and dealing with the disruptive French privateers. Other issues during his tenure included a smallpox epidemic in Newport, charter issues having to do with Rhode Island's militia serving in other colonies, and the ongoing border line disputes with the neighboring colonies.

The son of the Quaker governor, Nicholas Easton, the younger Easton was also a lifelong Quaker, and following his death in 1705 was buried in the Coddington Cemetery in Newport where his father and several other Quaker governors are also interred.

Early life

The son of Nicholas Easton, a President and Governor of the Rhode Island colony, John Easton was baptized at the parish church of St. Ethelfriede in Romsey, Hampshire, England on 19 December 1624.[1] His mother, Mary Kent, died in 1630 in England shortly after the birth and death of her fourth child.[2] At the age of nine, in late March 1634, Easton boarded the ship Mary and John at Southampton with his father and his older brother Peter, his only surviving sibling.[3]

Once in New England, the small Easton family settled first in Ipswich, and then later in Newbury, both in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[4] While in Newbury, Easton's father became an adherent of the dissident ministers John Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson. On 20 November 1637, the elder Easton was one of three Newbury men disarmed for his support of these ministers, and the following March he had license to depart the colony.[5] He then went to Winnecunnet, later Hampton, New Hampshire, but was ousted from there as well, and by the end of 1638 he was at Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island in the Narragansett Bay with other followers of Anne Hutchinson.[6]

Rhode Island

Easton, now a teenager, went with his father when he became a founder of Newport at the south end of the island in 1639, and it is here that the younger Easton lived the remainder of his life. In 1653, while less than 30 years old, Easton began a career of public service that would span more than four decades.[7] In this year he was elected to be attorney general for the island towns of Portsmouth and Newport, and the following year he became a Commissioner from Newport.[7] In 1655 he was made a freeman from Newport, and in 1656 he served his first of 16 years as the attorney general of the entire colony.[7] Easton continued to serve in multiple capacities, and in 1665 was a Deputy, and the following year served for his first of 18 terms as an Assistant.[7]

In 1674 Easton was elected deputy governor of the colony, serving under William Coddington. He served for two one-year terms in this office, being replaced in 1676 during King Philip's War with the militarily experienced John Cranston. In 1675 he wrote an account of the Indian war entitled, "A True Relation of what I know & of Reports & my Understanding concerning the Beginning & Progress of the War now between the English and the Indians."[7] The following year he was a member of a Court Martial at Newport for the trial of certain Indians charged with complicity in King Philip's designs.[7]

The period of time from 1676 to 1681 was one of the few periods when Easton did not serve in a public capacity.[7] Throughout the 1680s he was an Assistant, and in January 1690, following the three-year rule of Edmund Andros over all the New England colonies, he was one of the Assistants who wrote a letter to the new English monarchs, William and Mary, congratulating them on their accession to the throne, and informing them that Andros had been seized in Rhode Island, and returned to the Massachusetts Colony for confinement.[7]

Governorship

At the May 1690 elections, all members of the General Assembly were present, and the charter was publicly read as had been done before the Andros interposition.[8] The aged Henry Bull was elected as governor, but declined the position, and Easton was chosen to serve instead, with John Greene as deputy governor.[8] It was a special time in Rhode Island's history, described by Rhode Island historian and Lieutenant Governor Samuel G. Arnold as such:

The first grand period of Rhode Island history, the formation period, had now ended. An era of domestic strife and outward conflict for existence, of change and interruption, of doubt and gloom, anxiety and distress, had almost passed. The problem of self government was solved, and a new era of independent action commenced, which was to continue unbroken for an entire century, until her separate sovereignty should be merged in the American Union, by the adoption of the federal constitution; and her royal charter, the noble work of her republican founders, was never again to be interrupted, not even by the storm of revolution, until the lapse of more than a century and a half had made its provisions obsolete.[9]

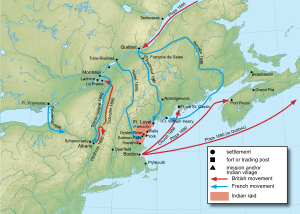

War with France

The governor, deputy governor and assistants were exempted from paying any colony tax because of the expenses they incurred in attending to their official duties and the fact that they received no salaries.[10] Easton held the governorship for a period of five years, during which period, England and her allies were engaged in the Nine Years War with France, and the New England colonists were left to deal with this war in North America, known as King William's War. Letters from other colonies came to Rhode Island asking for troops to aide in their efforts, and the reply was usually that the Rhode Island colony had a very exposed condition, and required its men to stay at home.[11] Nevertheless, In October 1690 the General Assembly agreed to raise 300 pounds for the prosecution of the war.[12] The colony now had nine towns: Providence, Portsmouth, Newport, Warwick, Westerly, Jamestown, New Shoreham (Block Island), Kings Town, and East Greenwich, each town being taxed for its portion of the levy.[12] Legislation was also applied to property appraisal, which in the past had been done by the "guess" method, and shipping was to be taxed, with all ships from other colonies being henceforth assessed a tax on cargoes unloaded at Newport.[12]

While the war was a major burden upon the colonists, one bright spot occurred in July 1690. As the colonies were being continuously harassed by French privateers, an expedition consisting of two sloops and 90 men under the command of Captain Thomas Paine went out from Newport to attack the enemy.[13] Paine approached five ships near Block Island, sent a few men ashore to prevent a French landing, then ran into shallow water to keep from being surrounded.[13] A late afternoon engagement ensued, lasting until nightfall, when the French withdrew, losing about half their men to casualties, while Paine's loss was one man killed and six wounded.[13] The brilliant exploit of Paine inspired the people of the colony with a naval spirit; this was the first victory for Rhode Island on the open sea.[14] French privateers, however, continued covering the seas, plundering the commerce of the colonists, and compelled a special session of the Assembly to adopt stringent measures for raising the tax levied but not yet collected.[14]

Other issues

In October 1691 the regular session of the General Assembly was held in Providence at the home of John Whipple (brother of Col. Joseph Whipple).[15] The smallpox had broken out on the island, and being a particularly virulent strain, it was nearly a year before the Assembly met again in Newport.[15]

On 7 October 1691 the Massachusetts and Plymouth Colonies united under a single charter, with William Phips assigned as governor.[16] The following year Phips announced to the Rhode Island colony that he had been appointed the commander-in-chief of all militia and other forces of the New England colonies, by sea and by land.[12] This was in direct conflict with the charters of both Rhode Island and Connecticut.[16] Captain Christopher Almy was sent to England to address this issue, to declare that the Royal Charter of 1663 gave control of troops to the Colony, and to present other issues of concern to the Rhode Island colony.[12][17] The outcome was that decisions rendered were all in Rhode Island's favor. The Rhode Island colony would have full control of its militia during times of peace, but during wartime would have a quota to offer the collective colonies.[18] Under this quota, Rhode Island was then assessed 48 men to be sent into the service of the Governor of New York.[18]

Another issue during Easton's tenure as governor greatly affected the Massachusetts Colony, but did not spill over into Rhode Island. This was the era of witchcraft, and in Rhode Island this offense appears on the statute book, but no prosecutions were ever made from it.[19] Historian Arnold wrote, "The people of this colony had suffered too much from the superstitions and the priestcraft of the Puritans, readily to adopt their delusions, and there was no State clergy to stimulate the whimsies of their parishioners. More important matters to them than the bedevilment of their neighbors engrossed their whole attention."[19]

Jurisdictional disputes with the Connecticut Colony continued, but a letter from that colony to Governor Easton in May 1692 struck a far more amicable tone than had earlier communications, and Easton replied in kind.[19] A new era of warmer feelings between the two rival colonies was ushered in, and the settlers in both colonies were satisfied with the easing of tensions.[19]

Death

After stepping down from being governor in 1695, Easton retired to a private life in Newport, where he died on 12 December 1705.[20] He was buried in the Coddington Cemetery on Farewell Street in Newport where several other Quaker governors of the colony are also interred.[20] He was the last of the Rhode Island colonial governors who came out of the exile of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, his father having been expelled from that colony as a follower of Anne Hutchinson.[20]

Family and legacy

In 1661, Easton married Mehitable Gaunt (or Gant), the daughter of Peter and Lydia Gaunt from nearby Plymouth Colony.[7] They had five children and at least 17 grandchildren.[7] They had been married less than 13 years when Mehitable died in late 1673, after which Easton married a woman named Alice, but had no children with her.[7]

Historian Thomas W. Bicknell wrote of Easton, "Governor Easton was one of the best qualified and most efficient of Colonial governors. His knowledge of the history of the Colony was complete, his judicial ability was tempered by long experience and careful study, and his great activity and energy, mental and physical, partook of the quality of men at life's meridian. Weakness in policy or vacillation in opinion found no lodgment in Governor Easton's administration."[21]

Ancestry

The ancestry of John Easton's father, Nicholas, was published by Jane Fletcher Fiske in the The New England Historical and Genealogical Register in 2000, and she published the ancestry of Easton's mother, Mary Kent, in the same journal in 2008 and 2009.[22][23][24]

| Ancestors of John Easton | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of colonial governors of Rhode Island

- List of lieutenant governors of Rhode Island

- Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

References

- ↑ Fiske 2000, p. 171.

- ↑ Fiske 2009, p. 59.

- ↑ Fiske 2000, p. 170.

- ↑ Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 396.

- ↑ Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 401.

- ↑ Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, pp. 401-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Austin 1887, p. 294.

- 1 2 Arnold 1859, p. 519.

- ↑ Arnold 1859, pp. 519-20.

- ↑ Arnold 1859, p. 520.

- ↑ Bicknell 1920, p. 1042.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bicknell 1920, p. 1043.

- 1 2 3 Arnold 1859, p. 521.

- 1 2 Arnold 1859, p. 522.

- 1 2 Arnold 1859, p. 523.

- 1 2 Arnold 1859, p. 524.

- ↑ Arnold 1859, p. 527.

- 1 2 Arnold 1859, p. 528.

- 1 2 3 4 Arnold 1859, p. 525.

- 1 2 3 Bicknell 1920, p. 1045.

- ↑ Bicknell 1920, p. 1044.

- ↑ Fiske 2000, pp. 159-171.

- ↑ Fiske 2008, pp. 245-255.

- ↑ Fiske 2009, pp. 51-65.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert C.; Sanborn, George F. Jr.; Sanborn, Melinde L. (2001). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. II C-F. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-110-8.

- Arnold, Samuel Greene (1859). History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol.1. New York: D. Appleton & Company. pp. 519–32.

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol.3. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 1041–5. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- Fiske, Jane Fletcher (April 2000). "The English Background of Nicholas Easton of Newport, Rhode Island". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. New England Historic Genealogical Society. 154: 159–171. ISSN 0028-4785.

- Fiske, Jane Fletcher (October 2008). "The English Background of Richard Kent, Sr. and Stephen Kent of Newbury, Massachusetts and Mary, Wife of Nicholas Easton of Newport, Rhode Island" (PDF). New England Historical and Genealogical Register. New England Historic Genealogical Society. 162: 245–255. ISSN 0028-4785.

- Fiske, Jane Fletcher (January 2009). "The English Background of Richard Kent, Sr. and Stephen Kent of Newbury, Massachusetts and Mary, Wife of Nicholas Easton of Newport, Rhode Island". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. New England Historic Genealogical Society. 163: 51–65. ISSN 0028-4785.