Isthmia (ancient city)

Shown within Greece | |

| Location | Kyras Vrysi, Corinthia, Greece |

|---|---|

| Region | Corinthia |

| Coordinates | 37°54′57.3372″N 22°59′35.4084″E / 37.915927000°N 22.993169000°ECoordinates: 37°54′57.3372″N 22°59′35.4084″E / 37.915927000°N 22.993169000°E |

| Type | City |

| History | |

| Founded | 690 to 650 BC |

| Abandoned | 470 BC |

| Periods | Archaic Greek |

| Satellite of | Isthmia |

Isthmia is an ancient city located on the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece. It is well known for being home to the Isthmian Games and is also the site of major Greek monuments, such as the Temple of Isthmia that honors the Greek God, Poseidon.[1]

Location

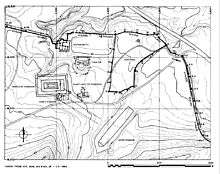

The city of Isthmia is located on the main road that connected Athens and Corinth [2] in the ancient world. This made it an easy stop for many travelers and therefore a logical geographic choice for the Panhellenic Games and monumental religious sanctuaries. Its location on the Isthmus and major ports created huge traffic through the city and established Isthmia as the hub for athletic and religious festivals; second in significance only to those at Olympia.[1]

History

Prehistoric times

Stone artifacts found on the site have been dated to show that humans have inhabited Corinthia since the Neolithic Era. Small samples of pottery dating to the last era of the Bronze Age (1600-1200 BC) show that people were still living in Isthmia during this time. During the Greek Dark Ages, the population declined throughout Greece, and with it came a deterioration of material wealth in Isthmia.[3]

Archaic period

As Greece moved into the Archaic period, writing, material culture, and population all increased.[3] The people of Isthmia began constructing large stone monuments and religious sanctuaries.[4] In the year 481 BC, the Persian Empire attempted to invade Greece. Isthmia was not a major battlefield, but its central location made it a preferred site for Greek conferences and pre–battle meetings.[3] The Archaic-style temple at Isthmia was badly burned in a fire in 480 BC, and the Doric-style temple remains were repaired using Classical architecture style elements.

Classical period

In the years 431–404 BC, Isthmia was caught in the middle of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. A second war between the two city-states occurred in the years 395–387 BC and the archaic temple for Poseidon was burned down in 390 BC.[3] It is unclear whether the destruction of the temple was a result of the dispute, but the lack of pottery found at the site after the fire indicates that Isthmia entered a period of decreased prosperity at this time.[4]

The Classical period also saw the rise of Philip II, King of Macedon. He united the Greek city–states, including Isthmia, in the 4th century BC, only to be assassinated in 336 BC. His successor, Alexander the Great, became one of Isthmia's most famous guests by calling a meeting in the city between the Greek city–states to discuss war with Persia.[3]

Roman control

In 196 BC, following the Second Macedonian War and the defeat of Macedon, the Roman Republic declared the "Freedom of the Greeks" from Macedonian hegemony. The decision to hold the political conference at Isthmia cemented its status as a symbol of Greek unity and freedom.[3]

In 146 BC, rising tensions between the Greek states and the increasingly hegemonic Romans resulted in a last attempt by the Achaean League to maintain its independence. The Achaean War ended in a quick Roman victory, and consul Lucius Mummius Achaicus ordered the complete destruction of Corinth as an example to all Greeks. The Altar of Poseidon was destroyed and control of the Isthmian Games was taken away from the city. It is not until 44 BC that Julius Caesar restored the stadium and temple to their original state.[3]

Late Roman, medieval, and early modern periods

In the 4th century AD, Emperor Constantine the Great banned all pagan religions and artifacts from Isthmia.[3] The Temple of Poseidon fell into disuse and its material was partly re-used for the building of the Hexamilion wall which was used as protection against invading barbarians in the 5thcentury.[2]

The Ottoman Empire captured Isthmia in 1423, and permamently in 1458. Isthmia was fought over by the Turks, Venetians, and local potentates for over three centuries. In 1715, the Venetians were expelled, and the Ottoman Empire controlled southern Greece for a hundred years until the Greek War of Independence.[3]

Oscar Broneer rediscovered the site at Isthmia in 1952. He excavated the temple, theater, two caves used for dining, and the two stadia used for the Isthmian Games.[4]

Monuments

Temples

The city of Isthmia houses many massive structures. The Archaic Temple of Poseidon, which was excavated in 1952 by Oscar Broneer,[5] was built in the Doric style in 700 BC.[2] The temple was constructed on a plateau, surrounded by valleys and considered the center of the Isthmian sanctuaries. The temple also housed shrines to gods related to Poseidon such as his son, Cyclopes, and the goddess Demeter. A multitude of other named divinities said to have been worshipped within the confines of the temple have links to Demeter, suggesting the Isthmian people's devotion to fertility and harvest.[6] Evidence including plates, bowls, and animal bones discovered within the ash on the plateau suggest that animal sacrifices of sheep, cattle, and goats took place at the temple on a regular basis and were often a cause for feasting and celebration.[7]

When it burned down in 480 BC, the roof, Sima (architecture), and columns were replaced using Classical style building elements. There was also a temple built for the god Apollo. Because of the similarities in construction style and building materials between these temples, it can be concluded that they were completed within two generations of building.[8] Isthmia was also home to a Roman temple that was built for the worship of Palaimon. The Temple to Palaimon was decorated with roof ornaments of the Ionic Order and had a cult following within the city.[9]

Stadiums

When the Isthmian Games were founded in 582 BC,[3] the people of Isthmia built a stadium for the sporting activities. The stadium was rebuilt in the Hellenistic period and featured a racetrack. The new stadium was built in the valley because the slope allowed for the accommodation of the mass quantities of spectators traveling to Isthmia for the festival.[4]

The East Field

On the eastern side of the temple there is a field that houses mazes of wall remnants. Archaeological evidence shows that these walls were poorly erected and built over each other many times throughout the city's history. These walls made small buildings, most likely houses, that had water facilities and food preparation areas.[10]

Culture

Isthmia's temples and stadiums highlight its religious, athletic, and political past. The first evidence of religious rituals, however, comes before the erection of the monumental sanctuary. In the Early Iron Age, cup and bowl fragments were found on the south-east side of the central plateau. They dated to the proto–geometric period and were surrounded by burnt bones that belonged to goats, sheep, and other animals sacrificed to Poseidon. Beginning in the late 8th century, evidence of a more defined sanctuary space is made with the construction of an altar and Temenos walls. Vessels made of both cheap and luxurious materials were found at this site. This suggests that the common people of Isthmia, not just the rich, were worshiping at the temple. The differences in the material quality of the vessels found at the site also suggests societal separation based on rank.[4]

During the 11th Century BC, archaeologists found the first appearance of religious pots, indicating that the citizens of Isthmia were practicing religious ceremony.[3] Vessels and pots from different time periods continued to be found at the site, suggesting that religious rituals for the people of Isthmia were continuous and long-lasting.[4]

In other archaeological excavations, 30 graves containing the remains of 69 people were dug at the city of Isthmia. The bodies have been dated to come from different time periods and are spread throughout the areas of excavation, suggesting that habitation in Isthmia was wide spread and deep-rooted.[11] The bodies are also buried using a variety of mortuary ritual processes, showing that Isthmia was an enduring, developing community.[12]

References

- 1 2 Irving, Jenni. "Isthmia." Ancient History Encyclopedia. N.p., 28 Apr. 2011. Web. 26 Oct. 2014

- 1 2 3 Gregory, Timothy. "The Sanctuary of Poseidon at Isthmia." OSU Excavations at Isthmia. The Ohio State University. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gregory, Timothy. "A Brief History of Isthmia." Ohio State Archaeological Excavations in Greece. The Ohio State University. Web. 16 Oct. 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gebhard, Elizabeth on ‘The Evolution of a Pan-Hellenic Sanctuary: From Archaeology towards History at Isthmia.’ pp. 154–177 in: Marinatos, Nanno and Hägg, Robin. Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches. London: Routledge. 1993. Print

- ↑ Greek Sanctuaries, New Approaches (1993, pp.154-177)

- ↑ Greek Sanctuaries, New Approaches (1993, pp.154-177)

- ↑ Greek Sanctuaries, New Approaches (1993, pp.154-177)

- ↑ Elizabeth, Gebhard R. "The Archaic Temple at Isthmia: Techniques of Construction." Archaische Griechische Tempel Und Altägypten. By Manfred Bietak. Wien: Verlag Der Österreichischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften, 2001. Print

- ↑ Gregory, Timothy. "Features of the Upper Sanctuary." OSU Excavations at Isthmia. The Ohio State University. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ Gregory, Timothy. "The East Field." OSU Excavations at Isthmia. The Ohio State University. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ Rife, Joseph L.. The Roman and Byzantine Graves and Human Remains. Vol. IX. Princeton (N. J.): American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2012. Print. pp. 113-152

- ↑ Rife, Joseph L.. The Roman and Byzantine Graves and Human Remains. Vol. IX. Princeton (N. J.): American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2012. Print. pp. 153-232.