Incidence geometry

In mathematics, incidence geometry is the study of incidence structures. A geometry such as the Euclidean plane is a complicated object that involves concepts such as length, angles, continuity, betweenness, and incidence. An incidence structure is what is obtained when all other concepts are removed and all that remains is the data about which points lie on which lines. Even with this severe limitation, theorems can be proved and interesting facts emerge concerning this structure. Such fundamental results remain valid when additional concepts are added to form a richer geometry. It sometimes happens that authors blur the distinction between a study and the objects of that study, so it is not surprising to find that some authors refer to incidence structures as incidence geometries.[1]

Incidence structures arise naturally and have been studied in various areas of mathematics. Consequently there are different terminologies to describe these objects. In graph theory they are called hypergraphs, and in combinatorial design theory they are called block designs. Besides the difference in terminology, each area approaches the subject differently and is interested in questions about these objects relevant to that discipline. Using geometric language, as is done in incidence geometry, shapes the topics and examples that are normally presented. It is, however, possible to translate the results from one discipline into the terminology of another, but this often leads to awkward and convoluted statements that do not appear to be natural outgrowths of the topics. In the examples selected for this article we use only those with a natural geometric flavor.

A special case that has generated much interest deals with finite sets of points in the Euclidean plane and what can be said about the number and types of (straight) lines they determine. Some results of this situation can extend to more general settings since only incidence properties are considered.

Incidence structures

An incidence structure (P, L, I) consists of a set P whose elements are called points, a disjoint set L whose elements are called lines and an incidence relation I between them, that is, a subset of P × L whose elements are called flags.[2] If (A, l) is a flag, we say that A is incident with l or that l is incident with A (the relation is symmetric), and write A I l. Intuitively, a point and line are in this relation if and only if the point is on the line. Given a point B and a line m which do not form a flag, that is, the point is not on the line, the pair (B, m) is called an anti-flag.

Distance in an incidence structure

There is no natural concept of distance (a metric) in an incidence structure. However, a combinatorial metric does exist in the corresponding incidence graph (Levi graph), namely the length of the shortest path between two vertices in this bipartite graph. The distance between two objects of an incidence structure – two points, two lines or a point and a line – can be defined to be the distance between the corresponding vertices in the incidence graph of the incidence structure.

Another way to define a distance again uses a graph-theoretic notion in a related structure, this time the collinearity graph of the incidence structure. The vertices of the collinearity graph are the points of the incidence structure and two points are joined if there exists a line incident with both points. The distance between two points of the incidence structure can then be defined as their distance in the collinearity graph.

When distance is considered in an incidence structure, it is necessary to mention how it is being defined.

Partial linear spaces

Incidence structures that are most studied are those that satisfy some additional properties (axioms), such as projective planes, affine planes, generalized polygons, partial geometries and near polygons. Very general incidence structures can be obtained by imposing "mild" conditions, such as:

A partial linear space is an incidence structure for which the following axioms are true:[3]

- Every pair of distinct points determines at most one line.

- Every line contains at least two distinct points.

In a partial linear space it is also true that every pair of distinct lines meet in at most one point. This statement does not have to be assumed as it is readily proved from axiom one above.

Further constraints are provided by the regularity conditions:

RLk: Each line is incident with the same number of points. If finite this number is often denoted by k.

RPr: Each point is incident with the same number of lines. If finite this number is often denoted by r.

The second axiom of a partial linear space implies that k > 1. Neither regularity condition implies the other, so it has to be assumed that r > 1.

A finite partial linear space satisfying both regularity conditions with k, r > 1 is called a tactical configuration.[4] Some authors refer to these simply as configurations,[5] or projective configurations.[6] If a tactical configuration has n points and m lines, then, by double counting the flags, the relationship nr = mk is established. A common notation refers to (nr, mk)-configurations. In the special case where n = m (and hence, r = k) the notation (nk, nk) is often simply written as (nk).

A linear space is a partial linear space such that:[7]

- Every pair of distinct points determines exactly one line.

Some authors add a "non-degeneracy" (or "non-triviality") axiom to the definition of a (partial) linear space, such as:

- There exist at least two distinct lines.[8]

This is used to rule out some very small examples (mainly when the sets P or L have fewer than two elements) that would normally be exceptions to general statements made about the incidence structures. An alternative to adding the axiom is to refer to incidence structures that do not satisfy the axiom as being trivial and those that do as non-trivial.

Each non-trivial linear space contains at least three points and three lines, so the simplest non-trivial linear space that can exist is a triangle.

A linear space having at least three points on every line is a Sylvester–Gallai design.

Fundamental geometric examples

Some of the basic concepts and terminology arises from geometric examples, particularly projective planes and affine planes.

Projective planes

A projective plane is a linear space in which:

- Every pair of distinct lines meet in exactly one point,

and that satisfies the non-degeneracy condition:

- There exist four points, no three of which are collinear.

There is a bijection between P and L in a projective plane. If P is a finite set, the projective plane is referred to as a finite projective plane. The order of a finite projective plane is n = k – 1, that is, one less than the number of points on a line. All known projective planes have orders that are prime powers. A projective plane of order n is an ((n2 + n + 1)n + 1) configuration.

The smallest projective plane has order two and is known as the Fano plane.

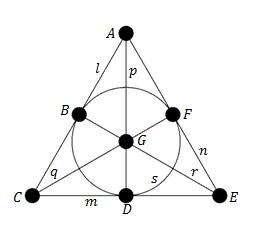

the Fano plane

Fano plane

This famous incidence geometry was developed by the Italian mathematician Gino Fano. In his work[9] on proving the independence of the set of axioms for projective n-space that he developed,[10] he produced a finite three-dimensional space with 15 points, 35 lines and 15 planes, in which each line had only three points on it.[11] The planes in this space consisted of seven points and seven lines and are now known as Fano planes.

The Fano plane can not be represented in the Euclidean plane using only points and straight line segments (i.e., it is not realizable). This is a consequence of the Sylvester–Gallai theorem.

A complete quadrangle consists of four points, no three of which are collinear. In the Fano plane, the three points not on a complete quadrangle are the diagonal points of that quadrangle and are collinear. This contradicts the Fano axiom, often used as an axiom for the Euclidean plane, which states that the three diagonal points of a complete quadrangle are never collinear.

Affine planes

An affine plane is a linear space satisfying:

- For any point A and line l not incident with it (an anti-flag) there is exactly one line m incident with A (that is, A I m), that does not meet l (known as Playfair's axiom),

and satisfying the non-degeneracy condition:

- There exists a triangle, i.e. three non-collinear points.

The lines l and m in the statement of Playfair's axiom are said to be parallel. Every affine plane can be uniquely extended to a projective plane. The order of a finite affine plane is k, the number of points on a line. An affine plane of order n is an ((n2)n + 1, (n2 + n)n) configuration.

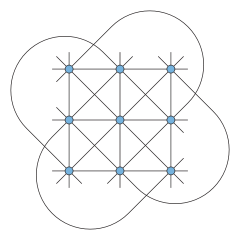

(Hesse configuration)

Hesse configuration

The affine plane of order three is a (94, 123) configuration. When embedded in some ambient space it is called the Hesse configuration. It is not realizable in the Euclidean plane but is realizable in the complex projective plane as the nine inflection points of an elliptic curve with the 12 lines incident with triples of these.

The 12 lines can be partitioned into four classes of three lines apiece where, in each class the lines are mutually disjoint. These classes are called parallel classes of lines. Adding four new points, each being added to all the lines of a single parallel class (so all of these lines now intersect), and one new line containing just these four new points produces the projective plane of order three, a (134) configuration. Conversely, starting with the projective plane of order three (it is unique) and removing any single line and all the points on that line produces this affine plane of order three (it is also unique).

Removing one point and the four lines that pass through that point (but not the other points on them) produces the (83) Möbius–Kantor configuration.

Partial geometries

%2C_the_Doily.svg.png)

Given an integer α ≥ 1, a tactical configuration satisfying:

- For every anti-flag (B, m) there are α flags (A, l) such that B I l and A I m,

is called a partial geometry. If there are s + 1 points on a line and t + 1 lines through a point, the notation for a partial geometry is pg(s, t, α).

If α = 1 these partial geometries are generalized quadrangles.

If α = s + 1 these are called Steiner systems.

Generalized polygons

For n > 2,[12] a generalized n-gon is a partial linear space whose incidence graph Γ has the property:

- The girth of Γ (length of the shortest cycle) is twice the diameter of Γ (the largest distance between two vertices, n in this case).

A generalized 2-gon is an incidence structure, which is not a partial linear space, consisting of at least two points and two lines with every point being incident with every line. The incidence graph of a generalized 2-gon is a complete bipartite graph.

A generalized n-gon contains no ordinary m-gon for 2 ≤ m < n and for every pair of objects (two points, two lines or a point and a line) there is an ordinary n-gon that contains them both.

Generalized 3-gons are projective planes. Generalized 4-gons are called generalized quadrangles. By the Feit-Higman theorem the only finite generalized n-gons with at least three points per line and three lines per point have n = 2, 3, 4, 6 or 8.

Near polygons

For a non-negative integer d a near 2d-gon is an incidence structure such that:

- The maximum distance (as measured in the collinearity graph) between two points is d, and

- For every point X and line l there is a unique point on l that is closest to X.

A near 0-gon is a point, while a near 2-gon is a line. The collinearity graph of a near 2-gon is a complete graph. A near 4-gon is a generalized quadrangle (possibly degenerate). Every finite generalized polygon except the projective planes is a near polygon. Any connected bipartite graph is a near polygon and any near polygon with precisely two points per line is a connected bipartite graph. Also, all dual polar spaces are near polygons.

Many near polygons are related to finite simple groups like the Mathieu groups and the Janko group J2. Moreover, the generalized 2d-gons, which are related to Groups of Lie type, are special cases of near 2d-gons.

Möbius planes

An abstract Mōbius plane (or inversive plane) is an incidence structure where, to avoid possible confusion with the terminology of the classical case, the lines are referred to as cycles or blocks.

Specifically, a Möbius plane is an incidence structure of points and cycles such that:

- Every triple of distinct points is incident with precisely one cycle.

- For any flag (P, z) and any point Q not incident with z there is a unique cycle z∗ with P I z∗, Q I z∗ and z ∩ z∗ = {P}. (The cycles are said to touch at P.)

- Every cycle has at least three points and there exists at least one cycle.

The incidence structure obtained at any point P of a Möbius plane by taking as points all the points other than P and as lines only those cycles that contain P (with P removed), is an affine plane. This structure is called the residual at P in design theory.

A finite Möbius plane of order m is a tactical configuration with k = m + 1 points per cycle that is a 3-design, specifically a 3-(m2 + 1, m + 1, 1) block design.

Incidence theorems in the Euclidean plane

The Sylvester-Gallai theorem

A question raised by J.J. Sylvester in 1893 and finally settled by Tibor Gallai concerned incidences of a finite set of points in the Euclidean plane.

Theorem (Sylvester-Gallai): A finite set of points in the Euclidean plane is either collinear or there exists a line incident with exactly two of the points.

A line containing exactly two of the points is called an ordinary line in this context. Sylvester was probably led to the question while pondering about the embeddability of the Hesse configuration.

The de Bruijn–Erdős theorem

A related result is the de Bruijn–Erdős theorem. Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn and Paul Erdős proved the result in the more general setting of projective planes, but it still holds in the Euclidean plane. The theorem is:[13]

- In a projective plane, every non-collinear set of n points determines at least n distinct lines.

As the authors pointed out, since their proof was combinatorial, the result holds in a larger setting, in fact in any incidence geometry in which there is a unique line through every pair of distinct points. They also mention that the Euclidean plane version can be proved from the Sylvester-Gallai theorem using induction.

The Szemerédi–Trotter theorem

A bound on the number of flags determined by a finite set of points and the lines they determine is given by:

Theorem (Szemerédi–Trotter): given n points and m lines in the plane, the number of flags (incident point-line pairs) is:

and this bound cannot be improved, except in terms of the implicit constants.

This result can be used to prove Beck's theorem.

Beck's theorem

Beck's theorem says that finite collections of points in the plane fall into one of two extremes; one where a large fraction of points lie on a single line, and one where a large number of lines are needed to connect all the points.

The theorem asserts the existence of positive constants C, K such that given any n points in the plane, at least one of the following statements is true:

- There is a line that contains at least n/C of the points.

- There exist at least n2/K lines, each of which contains at least two of the points.

In Beck's original argument, C is 100 and K is an unspecified constant; it is not known what the optimal values of C and K are.

More examples

- Projective geometries

- Moufang polygon

- Schläfli double six

- Reye configuration

- Cremona-Richmond configuration

- Kummer configuration

- Klein configuration

- Non-Desarguesian planes

See also

Notes

- ↑ As, for example, L. Storme does in his chapter on Finite Geometry in Colbourn & Dinitz (2007, pg. 702)

- ↑ Technically this is a rank two incidence structure, where rank refers to the number of types of objects under consideration (here, points and lines). Higher ranked structures are also studied, but several authors limit themselves to the rank two case, and we shall do so here.

- ↑ Moorhouse, pg.5

- ↑ Dembowski 1968, p. 5

- ↑ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1969), Introduction to Geometry, New York: John Wiley & Sons, p. 233, ISBN 0-471-50458-0

- ↑ Hilbert, David; Cohn-Vossen, Stephan (1952), Geometry and the Imagination (2nd ed.), Chelsea, pp. 94–170, ISBN 0-8284-1087-9

- ↑ Moorhouse, pg. 5

- ↑ There are several alternatives for this "non-triviality" axiom. This could be replaced by "there exist three points not on the same line" as is done in Batten & Beutelspacher (1993, pg. 1). There are other choices, but they must always be existence statements that rule out the very simple cases to exclude.

- ↑ Fano, G. (1892), "Sui postulati fondamentali della geometria proiettiva", Giornale di Matematiche, 30: 106–132

- ↑ Collino, Conte & Verra 2013, p. 6

- ↑ Malkevitch Finite Geometries? an AMS Featured Column

- ↑ The use of n in the name is standard and should not be confused with the number of points in a configuration.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "de Bruijn–Erdős Theorem" from MathWorld

References

- Batten, Lynn Margaret (1986), Combinatorics of Finite Geometries, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31857-2

- Batten, Lynn Margaret; Beutelspacher, Albrecht (1993), The Theory of Finite Linear Spaces, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-33317-2

- Buekenhout, Francis (1995), Handbook of Incidence Geometry: Buildings and Foundations, Elsevier B.V.

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd ed.), Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC, ISBN 1-58488-506-8

- Collino, Alberto; Conte, Alberto; Verra, Alessandro (2013). "On the life and scientific work of Gino Fano". arXiv:1311.7177

.

. - Dembowski, Peter (1968), Finite geometries, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 44, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-61786-8, MR 0233275

- Malkevitch, Joe. "Finite Geometries?". Retrieved Dec 2, 2013.

- Moorhouse, G. Eric. "Incidence Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 20, 2012.

- Ueberberg, Johannes (2011), Foundations of Incidence Geometry, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20972-7, ISBN 978-3-642-26960-8.

- Shult, Ernest E. (2011), Points and Lines, Universitext, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15627-4, ISBN 978-3-642-15626-7.

- Ball, Simeon (2015), Finite Geometry and Combinatorial Applications, London Mathematical Society Student Texts, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107518438.