Erkelenz

| Erkelenz | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Old town hall in Erkelenz | ||

| ||

Erkelenz | ||

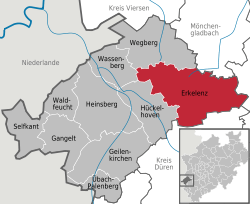

Location of Erkelenz within Heinsberg district  | ||

| Coordinates: 51°05′N 6°19′E / 51.083°N 6.317°ECoordinates: 51°05′N 6°19′E / 51.083°N 6.317°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia | |

| Admin. region | Cologne | |

| District | Heinsberg | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Peter Jansen (CDU) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 117.35 km2 (45.31 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 43,350 | |

| • Density | 370/km2 (960/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 41812 | |

| Dialling codes | 02431 | |

| Vehicle registration | HS, ERK, GK | |

| Website |

www | |

Erkelenz is a town in the Rhineland in western Germany that lies 15 kilometres (9 miles) southwest of Mönchengladbach on the northern edge of the Cologne Lowland, halfway between the Lower Rhine region and the Lower Meuse. It is a medium-sized town (over 44,000) and the largest in the district of Heinsberg in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Despite the town having more than 1,000 years of history and tradition, in 2006 the eastern part of the borough was cleared to make way for the Garzweiler II brown coal pit operated by RWE Power. This is planned to be in operation until 2045. Over five thousand people from ten villages have had to be resettled as a result. Since 2010, the inhabitants of the easternmost village of Pesch have left and most have moved to the new villages of Immerath and Borschemich in the areas of Kückhoven and Erkelenz-Nord.

Geography

Landscape

The area is characterised by the gently rolling to almost level countryside of the Jülich-Zülpich Börde, whose fertile loess soils are predominantly used for agriculture. Settlements and roads cover about 20 per cent of the area of the borough and only 2 per cent is wooded.[2][3] The Wahnenbusch, the largest contiguous wooded area, is located south of the town of Tenholt and covers 25 hectares (62 acres). In the north the börde gives way to the forests and waterways of the Schwalm–Nette-Plateau, part of the Lower Rhine Plain. In the west on the far side of the town, lies the Rur depression, some 30 to 60 metres lower (100 to 200 ft). Its transition is part of the Baal Riedelland. Here, streams have created a richly varying landscape of hills and valleys. In the east is the source region of the River Niers near Kuckum and Keyenberg. To the south the land climbs up towards the Jackerath loess ridge. The lowest point lies at 70 metres (230 ft) above sea level (NN) (Niers region in the northeast and near the Ophover Mill in the southwest) and the highest point is 110 metres (361 ft) above NN (on the boundary of the borough near Holzweiler/Immerath in the south).

Climate

The climate is influenced by the Atlantic Gulf Stream at the crossover between maritime and continental climates. The prevailing winds are from the southwest and there is precipitation all year round. Annual precipitation amounts to about 710 millimetres (28 in), whereby August is the wettest and September the driest month. Summers are warm and winters mild. In July the average temperature is 19 °C (66 °F) and, in January, 3 °C (37 °F). The length of the cold season with a minimum temperature below 0 °C (32 °F) is less than 60 days, the number of summer's days with temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F) averages 30, with an additional eight "tropical" days with daytime temperatures of more than 30 °C (86 °F) and night temperatures over 20 °C (68 °F), and there are an average of 20 days of thunderstorms. The onset of spring, which is reckoned from the budding of cherry, apple and pear trees, occurs between 29 April and 5 May. High summer, which begins with the harvest of winter rye, starts between 10 and 16 July.[4][5]

| Climate data for Erkelenz | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °F | 37.2 | 38.5 | 43.9 | 50.4 | 57.4 | 64.6 | 67.5 | 66 | 60.1 | 52.2 | 45.7 | 38.7 | 51.85 |

| Average precipitation inches | 1.98 | 2.37 | 1.807 | 1.827 | 2.693 | 2.413 | 2.811 | 3.303 | 1.335 | 2.705 | 2.323 | 2.374 | 27.941 |

| Daily mean °C | 2.9 | 3.6 | 6.6 | 10.2 | 14.1 | 18.1 | 19.7 | 18.9 | 15.6 | 11.2 | 7.6 | 3.7 | 11.02 |

| Average precipitation mm | 50.3 | 60.2 | 45.9 | 46.4 | 68.4 | 61.3 | 71.4 | 83.9 | 33.9 | 68.7 | 59.0 | 60.3 | 709.7 |

| Source: Erkelenz Weather Station, 2002 to 2006 data | |||||||||||||

Geology

The Erkelenz Börde is the northernmost extent of the Jülich Börde and is formed from a loess plateau that has an average thickness of over eleven metres in this area. Beneath it are the gravels and sands of the main ice age terrace, laid down by the Rhine and the Meuse. Embedded in the loess in places are lenses of marl that were mined until the 20th century in order to obtain lime by driving shafts and galleries underground.[6] In the Tertiary period the Erkelenz horst was formed along geological fault lines. East of the horst runs the Venlo fault block (Scholle), to the west is the Rur Scholle, to the south the Erft Scholle and the Jackerath Horst. A small section of the horst is part of the Wassenberg Horst. Thick seams of brown coal from the Tertiary and of black coal from the Carboniferous are located underground. The Erkelenz Horst is part of the Cologne Lowland Earthquake Region.

Borough

The town's administrative territory, or borough, is 20 kilometres (12 mi) across from east to west and 11 km (6.8 mi) from north to south. Its neighbouring administrative units, clockwise from the north, are:

- Town of Wegberg (8 km (5 mi) north, Heinsberg district)

- Independent town of Mönchengladbach, (15 km (9 mi) northeast)

- Municipality of Jüchen (14 km (9 mi) east, Rhein-Kreis Neuss district)

- Municipality of Titz (12 km (7 mi) southeast, Düren district)

- Town of Linnich (11 km (7 mi) southwest, Düren district)

- Town of Hückelhoven (7 km (4 mi) west, Heinsberg district)

- Town of Wassenberg (11 km (7 mi) northwest, Heinsberg district)

The town of Erkelenz emerged in its present configuration as a result of the Aachen land reform bill of 21 December 1971 (the Aachen-Gesetz). According to this law inter alia the former districts of Erkelenz and Geilenkirchen-Heinsberg were to be merged on 1 January 1972. Erkelenz lost its status as the county town to Heinsberg and was amalgamated with the municipalities of Borschemich, Gerderath, Golkrath, Granterath, Holzweiler, Immerath, Keyenberg, Kückhoven, Lövenich, Schwanenberg and Venrath, as well as the parishes of Geneiken and Kuckum. The area of its borough increased from 25.22 to 117.45 square kilometres (9.7 to 45.3 sq mi).[7]

According to the law, the borough of Erkelenz is divided into nine districts with a total of 46 villages and hamlets (population as at 31 October 2009):[8]

- District 1: Erkelenz with the villages of Oestrich and Buscherhof as well as Borschemich, Borschemich (new), Bellinghoven and Oerath, a total of 20,173 inhabitants

- District 2: Gerderath with Fronderath, Gerderhahn, Moorheide and Vossem, a total of 5,179 inhabitants

- District 3: Schwanenberg with Geneiken, Genfeld, Genhof, Grambusch and Lentholt, a total of 2,265 inhabitants

- District 4: Golkrath with Houverath, Houverather Heide, Hoven and Matzerath, a total of 2,039 inhabitants

- District 5: Granterath and Hetzerath with Commerden, Genehen, Scheidt and Tenholt, a total of 3,488 inhabitants

- District 6: Lövenich with Katzem and Kleinbouslar, a total of 4,147 inhabitants

- District 7: Kückhoven, a total of 2,250 inhabitants

- District 8: Keyenberg and Venrath with Berverath, Etgenbusch, Kaulhausen, Kuckum, Mennekrath, Neuhaus, Oberwestrich, Terheeg, Unterwestrich and Wockerath, a total of 3,468 inhabitants

- District 9: Holzweiler and Immerath (new) with Lützerath and Pesch, a total of 2,372 inhabitants

Coat of arms

The coat of arms is parted horizontally. The upper part is blue, and contains the golden lion of the duchy of Guelders (Geldern). In the silver (white) lower part is a red medlar, also called rose of Geldern. The coat of arms shows the centuries-old connection to the duchy. The colours from the shield became the colours of the city: blue and white.

History

Pre- and early history

There have been discoveries of Old and New Stone Age flint-knapping sites across the whole of the present area of the borough.[9] Near Haberg House, north of Lövenich, there is a site of national renown. Near Kückhoven a wooden well was discovered in 1990 that belonged to a settlement of the Linear Pottery culture and had been built around 5,100 B.C. This makes it one of the oldest wooden structures in the world.[10] North of the old village of Erkelenz, on the present day Mary Way (Marienweg), lay three cremation graves (Brandgräber), northwest to south of numerous fields of rubble. Roman bricks, hypocaust bricks and shards come from the marketplace south of the town hall. Here in the southwest corner and east of the chancel of the Roman Catholic parish church there are urn graves enclosed by glacial erratics of the early Frankish period from 300 to 500 A.D. On the south and southeast edge of the market, round jars were also found in the style of Badorf ceramics from Carolingian times.[11] In 1906 a Roman Jupiter Column from the beginning of the 3rd century A.D. was discovered in Kleinbouslar. The Erkelenz chronicler Mathias Baux wrote in the 16th century that "the bushes in the middle period were cleared and the soil turned into fertile fields, so that out of the harsh wilderness a corn-rich land and overall a breezy paradise was established."[12] From Mathias Baux's perspective, the middle period was the 8th century, which corresponds to the emergence of the Carolingian Empire. Under the present-day Catholic church lay Frankish and medieval graves without any grave goods as well as broken pieces of Badorf Ceramic and Roman bricks.[13]

Origin of the name

The overwhelming theory is that the name Erkelenz belongs to the group of Gallo-Romance -(i)acum placenames. According to this view the name of the town, which first appears in the records in a document dating to 966 A.D. sealed by Otto the Great as herclinze, comes from fundus herculentiacus: Herculentian estate (Estate of Herculentius). From the original adjectival character of the personal name the neuter noun Herculentiacum developed. However a continuity of settlement from Roman to Frankish times cannot be proven.[14] As a result, it is also postulated that the name does not have Roman, but Old High German origins, according to which the word linta = lime tree.[15] In 1118 A.D. the name of the place finally appears as Erkelenze.

Manorialism

On 17 January 966, St. Mary's Abbey in Aachen (Marienstift zu Aachen) was given inter alia the settlements of Erkelenz and its neighbour, Oestrich, in the County of Eremfried in the Mühlgau as part of an exchange with the Lotharingian Count Immo. Emperor Otto the Great confirmed this exchange in the aforementioned deed at an imperial assembly (Hoftag) in Aachen.[16] From then on the abbey was the owner of the entire estate in Erkelenz and the surrounding villages with the proviso that territorial lordship was exercised by the count.[17] Later the estates owned by the abbey were divided between the provost and chapter. The farms were not managed independently, but were leased. Not until 1803 did the abbey lose these rights of ownership, when France introduced secularisation into the Rhineland.[18]

Town rights

Erkelenz received its town rights in 1326 from Count Reginald II of Guelders, as can be read in the town chronicle by Matthias Baux.[12][19] But no deed granting town rights exists, which is why it has been suggested that there was no fixed date but, instead, a long drawn-out process of becoming a town over many years that may have dragged on into the 14th century.[20][21] However, against that is the fact that there is a jury seal dating to the year 1331,[22] and that Erkelenz appears on the Guelders urban diet on 1 December 1343.[23] In 1359 Erkelenz is described in a document as a Guelders town[11] and bears the Guelders lions and rose on its seal and coat of arms.

Territorial lordship

From the end of the 11th century the counts of Guelders, the first being Gerard III of Wassenberg, also known as Gerard I, Count of Guelders,[24] also possessed the lordship in Erkelenz. They were advocates appointed by the Holy Roman Empire and exercise jurisdiction, trade protection and military command.[25] In 1339 Emperor Louis the Bavarian elevated Guelders to a dukedom, under Rainald II,[24] that was divided into four "quarters" (Quartiere). Erkelenz and its surrounding villages belonged to the upper quarter (Oberquartier) of Guelders with its main centre at Roermond and was an exclave of Guelders within the Duchy of Jülich. It formed the Amt of Erkelenz, together with the non-isolated villages of Wegberg, Krüchten and Brempt, headed by the Amtmann (Drossard).[26]

The town's constitution and administration was consistent with those of the other towns in Guelders. Seven magistrates (Schöffen) who, like the mayors, had to possess wealth in the town or the county, and ten common councillors put forward two candidates for the office of town mayor (Stadtbürgermeister) and two for that of county mayor (Landbürgermeister) for a period of office of one year, but they were elected only by the magistrates, who actually ran the administration of the town, whilst the council only fulfilled representative functions.[27]

Soon after its elevation to town status, work began on the brick fortifications of the place. These probably consisted of basic ramparts as had been common since time immemorial for the defence of settlements,[10] which had been started in the 11th century.[28] Although the castle was not documented until 1349,[29] the town appeared to have developed under the protection of the castle along the Pangel, the oldest mentioned street (in deme Pandale, 1398) which was in its immediate vicinity. The nearby Johannismarkt (alder mart , Engl.: old market, 1420) and the more distant square known today simply as Markt ("market"), then referred to as the niewer mart (Engl.: new market, 1480), were also mentioned.[30] In addition the castle had clearly been built within the town walls, so that it must have been there at least when town rights were granted in 1326.[31][32] It is also hardly likely that an undefended place would have been elevated to the status of a town. Finally, the first and strongest town gateway, the Brück Gate (Brücktor, on Brückstraße) was built in 1355 on the Cologne Military Road (Kölner Heerbahn) that came from Roermond to Erkelenz and ran along the Theodor-Körner Road, Mühlenstraße and Wockerath to Cologne.[33]

In a feud between Edward of Guelders, who was a son of Duke Reginald II and adversary of his elder brother, Reginald III,[24] Count Engelbert III of the Mark conquered the now insufficiently fortified town in 1371 and partly destroyed it.[34] The childless Edward fell in the same year on the battlefield of Baesweiler fighting on the side of his brother in law, Duke William II of Jülich, against Duke Wenceslaus I of Brabant.[35] When in that year his brother, Rainald III, also died without issue,[24] fighting broke out repeatedly over the inheritance and possession of the Duchy of Guelders under which Erkelenz, as an exclave of Guelders in the state of Jülich, suffered particularly severely from the burdens of war, quartering of soldiers, robbery and plundering.[36]

The construction of fortifications at Erkelenz was brought forward to meet the strategic requirements of its local lords. Built in 1416 under Reginald IV of Guelders, opposite the Brück Gate (Brücktor) on the other side of town, was the Maar Gate (Maartor, Aachener Strasse),[12] which faced the Jülich, south of the town. In 1423, the Duchy of Guelders, and thus the town of Erkelenz, fell to Arnold of Egmond,[33] and, in 1425, to Adolphus of Jülich-Berg.[24] After his nephew and successor, Gerhard II of Jülich-Berg had defeated Arnold of Egmond in the Battle of Linnich, the Oerath Gate (Oerather Tor, Roermonder Straße)) was completed in 1454,[12] that faced Roermond. Despite the increasing cost of work on the fortifications, the town was able to afford it. In 1458 it immediately started work on a new bell tower, that has survived until today, after the tower of the old Romanesque church had collapsed.

In 1473 the town came into the possession of Charles the Bold of Burgundy who, whilst at war against Lorraine in 1476, personally accepted the homage of the townsfolk of Erkelenz. In 1481 the town fell to Maximilian I of Austria and, in 1492, to the son of Arnold of Egmond, Charles of Egmond, who also presented himself personally in the same year at Erkelenz. At that time the fortress of Erkelenz was so strong that Maximilian I instructed the Dukes of Jülich and Kleve, who were allied with him against Guelders, not to engage in a bombardment of the town, but to take them with the aid of storming bridges (Sturmbrücken). Using that method, an army of 3000 foot soldiers and 1,000 horse under William IV of Jülich took them by surprise in August 1498.[37] In 1500 the town fell again to Charles of Egmont,[33] so that in 1514 the gate opposite the Oerath Gate opposite the Bellinghoven Gate (Bellinghovener Tor, Kölner Straße) was built,[12] which sealed a gap facing Julich. There were 14 defensive towers in the town wall with its four gate castles (Torburgen) and, in front of it was a second wall, separated by a moat.[12] The town was thus considered impregnable.

In 1538 Guelders fell to William of Jülich, Cleves and Berg[33] During that period the great town fire of 1540 occurred on 21 June of that year. The fire broke out during a summer heatwave, almost entirely razing the town apart from few houses by the Brück Gate and on Maarstraße. Help came from the neighbouring Guelders towns of Roermond and Venlo. Emperor Charles V who, in 1543, following the capture of Düren and Julich during his march on Roermond with a 30,000 strong army, stayed personally in Erkelenz.[38][39] ended the Guelders succession wars at the Treaty of Venlo. The town now ended up, together with the Duchy of Guelders, under to the Spanish House of Habsburg and was part of the Spanish Netherlands,[33] then the richest country in Europe. So, for example, the town was able, as the inscription on a rock near the entrance testifies, to replace the destroyed town hall as early as 1546 with a new building that is still standing.[40]

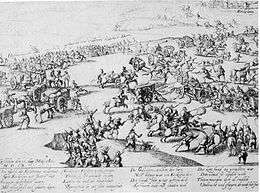

Lasting peace did not, however, return to the land and several times epidemics struck the town. In 1580 it was almost completely depopulated by the plague.[41] During the Spanish-Dutch War in 1607, Dutch troops took the town and plundered it. After Erkelenz had been unsuccessfully besieged in 1610 during the Jülich-Cleves War of Succession, the army of the French king, Louis XIV, allied with the troops of the Archbishop of Cologne, was finally in a position to take the town on the evening of 9 May 1674. This attack which took place during the French-Dutch War only succeeded on the fourth assault using the newly invented cannons, when two of the four gates fell. On that day, the town ceased to be a fortification. The attackers are reported to have lost 400 dead, the defenders just six. The invaders forced the townsfolk to breach the walls and blew up the Bellinghoven and Oerath gates, both of which blocked free passage to the Netherlands.[42][43]

In the War of Spanish Succession, Erkelenz was occupied by Prussian troops in 1702 who did not leave again until 1713. In the Treaty of Utrecht in 1714 Duke John William of Jülich and Elector Palatine (of Palatinate-Neuburg) was given Erkelenz; the town not paying him homage until 1719. The town thus lost its centuries-old affiliation with the Upper Quarter of Guelders. From 1727 to 1754 the territory of Erkelenz (Herrlichkeit Erkelenz) was pledged to Freiherr von Francken,[33] who also stayed from time to time in the town.

From 1794 to 1815 it belonged to France, along with the lands left of the Rhine, and was given a permanent contingent of French troops. Initially Erkelenz formed a municipality (Munizipalität), from 1800 a mairie (mayoralty) and, from 1798, was the seat of the canton of Erkelenz in the arrondissement of Crefeld, which was part of the Département de la Roer.[44] In 1815 the King of Prussia became the new landlord following Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo. In the years 1818/19 the tumbledown town walls and gates were demolished. Instead of walls the four present-day promenade streets were built, each named after their respective points of the compass.[45][46] From 1816 to 1972 Erkelenz was the seat of the rural district of Erkelenz (Kreis Erkelenz).

Industrialisation

Around 1825 Andreas Polke from Ratibor took up residence in the town and founded a pin factory. The nearby region around Aachen was a leading light in this trade at the time. In 1841 Polke employed 73 workers in his factory, of whom 36 were child workers under 14; for those of school age he ran a factory school. Pins were made in Erkelenz until about 1870. In 1852 Erkelenz was connected to the Aachen–Mönchengladbach railway and, in addition to a railway station for passenger services, was also given a goods station with marshalling sidings, a hump and a turntable. The increased volume of traffic into Erkelenz station necessitated an upgrade of the four roads radiating from the town to something like chaussee standard[47] and in the succeeding decades a development of the town beyond its medieval town boundaries along the present Kölner Straße towards the station.

In the 19th century hand weaving with looms was the predominant activity of the surrounding villages. The Industrial Age in Erkelenz first began with the introduction of mechanical weaving looms for making cloth. In 1854 the Rockstoff Factory I.B. Oellers, was established on the present Parkweg; it was a mechanical weaving mill which, at times, employed 120 workers and 20 salesmen. In 1872 the mechanical plush weaving mill of Karl Müller (corner of Kölner Straße and Heinrich Jansen Weg) was founded; it employed 60 hand weavers in Erkelenz and another 400 in the regions of Berg and the Rhön area for the main Erkelenz operation. In 1897 the Halcour Textile Factory appeared on Neußer Straße, which had 67 male and 22 female workers in 1911 in its factory-owned health insurance department.[48]

The town's actual step into the Industrial Age took place in 1897 when the industrial pioneer, Anton Raky, moved the head office of the International Drilling Company (Internationaler Bohrgesellschaft), known locally as the Bohr, to Erkelenz. Key factors in choosing this location were the favourable railway links to the Ruhr area and the Aachen Coalfield. In the years that followed industrial workers and engineers flocked to Erkelenz, creating a shortage of housing, a situation that could only be alleviated by establishing a charitable building association.[49] Between the town centre and the railway line, a new quarter emerged, known colloquially as Kairo (pronounced: Kah-ee-roh) due to the little foreign looking towers on many of the houses. In 1909 the drilling firm employed 50 staff and 460 workers. During the wartime year of 1916 it had as many as 1,600 employees. When, on 10 May 1898, a bronze statue of Emperor William I was erected on the market place, it was illuminated, at Raky's initiative, with electric lighting from arc lamps. That marked the introduction of electricity into the public arena in Erkelenz. In the same year the first street lamps were erected in Bahnhofstraße (today Kölner Straße) and the first mains electricity was delivered to houses.

Gründerzeit house façades are witnesses to the development at the turn of the century. In the next two decades the town built the waterworks on the present Bernhard-Hahn-Straße with its water tower visible for miles, the electricity works, the slaughterhouse, the swimming baths and a large school building for the gymnasium on the Südpromenade. The founding of a korn distillery, a brewery, a malthouse and a dairy acted as new outlets for agriculture. In 1910 Arnold Koepe built an engineering workshop in the former Karl Müller plush weaving mill in order to manufacture coal wagons for the mines. In 1916 Ferdinand Clasen took over the operation and in 1920 founded the Erkelenz Engineering Factory (Erkelenzer Maschinenfabrik) from this firm on Bernhard-Hahn-Straße that employed up to 200 workers.[50]

World wars and inter-war years

During the First World War the local economy also ground to a halt as a result of conscription, the priority given to the transportation of troops and war materiel on the railways as well as the large contingents of troops that marched through the town with their resulting demands. To alleviate the lack of labour, prisoners of war, mainly Russians who had been interned in 1915 in a POW camp on the land of the International Drilling Company, were employed, mainly in agriculture. In order to meet the wartime demand for metal, the townsfolk had to give up relevant implements and the church had to donate some of its bells in return for little compensation. The lost war cost the lives of 142 Erkelenz townsfolk in Army service and another 155 were injured, some seriously.[51]

After this war, which also saw the end of the German Empire 2,000 soldiers were stationed here between 1918 and 1926. French troops were quartered here until 19 November 1919 and then Belgian troops took over from 1 December 1919. Huts were erected on Neusser Straße and Tenholter Straße as soldiers' quarters, in addition to commandeered houses, flats were built on Freiheitsplatz, on Graf-Reinald-Straße and Glück-auf-Straße for the officers and NCOs.[52] Because gold and silver had to be given up at the beginning of the war and the gold standard had been replaced by paper money, the cost of all goods rose dramatically, despite the command economy, to paper money prices that were scarcely affordable, so that the supply of paper money finally ran out and the communal authorities were permitted to print their own paper money. In 1921 the town had emergency money printed in the shape of paper notes with values of 50 and 75 pfennigs to a total value of 70,000 marks. This emergency currency went into partial circulation, but was withdrawn again in 1922.[53]

When the French and Belgians occupied the Ruhr in January 1923, in order to take coal and steel back to their own countries, there was passive resistance, which later became known as the Battle of the Ruhr (Ruhrkampf). In Erkelenz this passive resistance was carried out especially by railwaymen, in the course of which the Belgian secret police expelled 14 families, including small children, who had been reported by narks. They were abandoned, in some cases using force, in remote places at night and in fog.[54]

Right from the start of the occupation France and Belgium had tried unsuccessfully to annexe the Rhineland. Now, using the excuse of the resistance that had flared up, they tried to take it by force. In Aachen Separatist troops, which had established themselves by force of arms in various Rhenish towns, called for a Rhenish Republic. On 21 October 1923 such a force also appeared in Erkelenz, hoisted the Rhenish flag over the town hall and the courthouse by force of arms under the protection of the Belgians and demanded that the municipal and state officials now serve the Rhenish Republic. Officials and townsfolk refused and hauled down the separatist flag the following day. To the great joy of the population, the occupying troops pulled out a year later on 31 January 1926 in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles. The bells of all the churches rang at midnight, their hour of freedom,[55] and that year Erkelenz also celebrated the 600th anniversary of being granted its town rights.

After Hitler had seized power on 30 January 1933 and after the Reichstag and local elections had been held in March 1933, the Nazis in Erkelenz under the leadership of Nazi Kreisleiter, Kurt Horst, began, using the authority of the municipal "parliaments", to rename all the roads and squares after their own leaders.[56] For example, from April 1933 Erkelenz had an Adolf Hitler Platz (Johannismarkt), a Hermann Göring Platz (Martin Luther Platz) and a Horst Wessel Straße (Brückstraße).[57] In May 1933 they forced the incumbent democratic mayor, Dr. Ernst de Werth, out of office under threat of taking him into "protective custody", made Adolf Hitler an honorary citizen and pursued political dissidents, trades unionists and clergymen.[58]

In July 1933 a so-called Hereditary Health Court was established at the district courthouse in Erkelenz as in all districts in the German Empire, whose task was to direct the forced sterilisation of mentally and physically handicapped people as part of what later became Hitler's "Euthanasia Programme", known after the war as Action T4. This programme of Nazi violence saw the systematic murder of those seen by the Nazis as "asocial", "inferior" and "unworthy of living". In Erkelenz, such people ended up in Nazareth House in Immerath.[59]

By April 1933 the NSDAP had organised a boycott of Jewish businesses in the town,[60] whilst the 1938 November pogroms (the so-called Reichskristallnacht) finally led to anti-Semitic acts of violence. The synagogue on the Westpromenade was devastated by mobs commanded by the SS and SA, Jews were arrested and Jewish businesses in the town were plundered and demolished.[61] In March/April 1941 Jews all over Germany were evacuated from their homes and concentrated in so-called Jew houses (Judenhäusern), to which they were only permitted to take the absolute essentials from their property.[62] In Erkelenz on 1 April 1941 the Nazis forced the remaining Jews in the town of Erkelenz to leave their homes and take up residence in the Spiess Hof, a farmstead in Hetzerath, from where they were deported in 1942 via the Izbica Ghetto to the extermination camps.[63]

Towards the end of the Second World War, as the Allies advanced towards Germany's western border in the middle of September 1944, Erkelenz was gradually cleared out, like many other places in the Aachen region. Whilst long streams of refugees moved eastwards across the Rhine, as well as groups of fieldwork labourers there were large units of armed SA in the border region who tyrannised and robbed the remaining population.[64] As part of the "Rur Front", anti-tank ditches were dug two kilometres (1.2 miles) west of the town in a semi-circular arc, minefields were sewn and infantry positions were constructed with extensively branched trenches in order to create a strong hedgehog defence. The first major carpet bombing air raid took place on 8 October 1944 over the town. During the second air raid on 6 December 1944 44 people died. Between the major carpet bomb attacks, non-stop fighter bomber raids went on from dawn to dusk and often into the night, continuing the work of destruction by strafing and bombing. From December 1944 the town also came within the range of allied artillery. During a further bombing raid on 16 January 1945, 31 people were killed, including 16 in one bunker on Anton Raky Allee. Amongst the SS combat troops, the command was issued from the top to the lowest level to pull out and they did so, as did the local party functionaries, who had been burning their records for days. The fourth and heaviest air raid on the now abandoned town took place on 23 February 1945. About 90 four-engined bombers flew over in two waves. Everything that had survived the war to that point now lay in ashes: the churches, the community hall, the courthouse, the swimming baths, the hospital, the schools and the kindergarten; only the tower of the Roman Catholic parish church remained standing, albeit badly damaged. When, three days later, on 26 February 1945, American armoured units of the 102nd US Infantry Division of the 9th US Army entered the town and the surrounding villages, the warning signs on the minefields indicated the safe lanes because there was no one left who could have removed them. About Volkssturm troops gave themselves up without a fight. At the end of this war, Erkelenz was largely destroyed and counted 300 killed in air raids, 1,312 dead and 974 wounded within the county of Erkelenz.[65][66]

The post-war period

As Allied forces invaded the area, the inhabitants of the surrounding villages had to leave their houses and for many days and weeks, they were driven from one place to another or concentrated in camps without enough supplies, whilst their homes were plundered, wrecked and, in many cases, set on fire. In addition, former Russian forced labourers, who were concentrated into the nearby village of Hetzerath, armed themselves with war materiel that had been left lying around and threatened town and country by robbing, killing and starting fires. The logistic troops of the invading forces also stole on a grand scale. By the end of March 1945 about 25 people still lived in Erkelenz and, as the town gradually filled up with retreating evacuees, they lacked all the basic necessities.[67]

In early June 1945, British troops replaced the Americans. Several of the leading Nazis, who were found among those retreating, were arrested and placed on trial. So-called "Persil notes" (Persilscheine) were much sought after. The majority of the lower-ranking Nazis and their followers were forced into clearing rubble and cleaning up the town. But the remaining townsfolk, especially farmers who still had a horse or ox and cart, were also called upon to supply manual labour or transport. Even the youth were encouraged to volunteer for work details in order to help with the rebuilding of the town. The nature of most of the work was self-help and the newly reorganised town government only focussed on those building regulations that were absolutely necessary.

The first general municipal elections took place on 15 September 1946. From 1947‚ CARE Packages arrived in the town, filled with food and such like, mainly sent by Americans of German origin. Apart from the returning population of the town, increasing numbers of refugees from Germany's eastern territories had to be absorbed, so that in the 1950s a new quarter of the town, Flachsfeld, was built. At the same time, the town also spread out over the fields between the few houses of Buscherhof and the Oerath Mill, forming a new large quarter, the Marienviertel. Almost all its roads, which lay on both sides of the old Marienweg, a Marian pilgrimage route that ran to Holtum, bore the names of east German towns. Not until 1956 and 1957 did the town's population receive the last repatriates from the war and from POW camps at Erkelenz Station.

Chronological summary

- 966: Erkelenz was first mentioned in a document as Herclinze, 1118 as Erkelenze.

- 1326: Erkelenz received town rights from the count of Guelders. (1339 the noble man became duke.) The area of Erkelenz was an exclave of the duchy of Guelders in the duchy of Jülich. The town belonged to the Upper Quarter Roermond.

- 1543: The Spanish Netherlands (Spanish Habsburg) got Erkelenz.

- 1713: After the War of the Spanish succession the duke of Jülich, who was also prince of palatine (Pfalz-Neuburg) received the town.

- 1794: France invaded the area, Erkelenz belonged to this state and became the capital of the district Canton Erkelenz in the Roer département.

- 1815: After the defeat of Napoleon Erkelenz became part of Prussia. The district was now called Kreis Erkelenz.

- 1818/1819: The medieval walls and gates of the town were demolished.

- 1852: The railway Aachen–Düsseldorf was built

- 1897: The engineer Anton Raky established a drilling machine factory, today WIRTH Group.

- 1938: The synagogue was desecrated.

- 26 February 1945: Erkelenz was captured by the 407th infantry regiment of the U.S. 102nd Infantry Division (Ozarks), US Ninth Army.

- 1945: The machine factory Hegenscheidt relocated from Ratibor to Erkelenz.

- 1972: The district Kreis Erkelenz was abolished, it became part of the Kreis Heinsberg. The area of the town Erkelenz was enlarged from 25.3 square kilometres (9.77 sq mi) to 117.35 square kilometres (45.31 sq mi).

Population development

- 1812 :3.370

- 1861 :4.148

- 1895 :4.168

- 1900 :4.612

- 1925 :6.605

- 1935 :7.162

- 1946 :6.348

- 1950 :7.475

- 1960 :11.876

- 1970 :12.807

- 1980 :38.175

- 1990 :39.957

- 2000 :43.194

- 2005 :44.625

- 2010 :44.457

Mayors since 1814

|

|

Twin towns

Saint-James in France, on the border between Brittany and Normandy, near to Mont Saint-Michel.

Education

In Erkelenz there are ten primary schools, two secondary schools (Hauptschule), 1 secondary modern school (Realschule), two high schools Cornelius-Burgh-Gymnasium, Cusanus-Gymnasium Erkelenz Europaschule), one business college (Berufskolleg des Kreises Heinsberg in Erkelenz) and one school for persons with learning disabilities.

Transportation

- Motorway Bundesautobahn 46

- Motorway Bundesautobahn 61

- Erkelenz station on the Aachen–Mönchengladbach railway, operated by Deutsche Bahn

Buildings

- Altes Rathaus - The old cityhall (1546 AD)

- Kirchturm - The steeple of the catholic church St. Lambertus (1458 AD)

- Burg - The castle (1377 AD)

Museum

There is a Fire-brigade museum in the village of Lövenich.

Personalities

This section mentions some well-known persons who have been born and raised in Erkelenz, who have worked here or whose name is closely connected with the city:

- Arnold von Harff (1471-1505), the knight and pilgrim lived from 1499 on a not survived castle behind today's estate Nierhoven at Lövenich.

- Theodoor van Loon (1581/1582-1649), Flemish painter of the Baroque

- Reinhold Vasters (1827-1909), goldsmith for sacred art and master falsifiers

- Leo Heinrichs (1867-1908) Father in the Franciscan Order, was shot by an anarchist in Denver during the Holy Mass in 1908, the beatification procedure is initiated.

- Joseph Hahn (1883-1944), member of the German Center Party, editor of the newspaper Erkelenzer Kreisblatt , 1944 imprisoned for several weeks in the course of the Aktionthunder, died after his release in the same year the consequences of his concentration camp - imprisonment.

- Werner Müller (1900-1982), Director of the Bohr-company, was sentenced on 14 October 1943 by the Volksgerichtshof to death for Wehrkraftzersetzung, pardoned for life in February 1944, survived and rebuilt the drill rig after the war. From February 12 to October 12, 1946, he had been nominated by the British military government as district administrator of Erkelenz County.

- Dickie Peterson (1946–2009), co-founder of heavy metal band Blue Cheer, who lived in Germany for extensive periods. Died in Erkelenz.

- Lewis Holtby (born 1990), German-British footballer currently playing for Hamburger SV

- Michael Bauer, the artist, was born here in 1973.

References

- ↑ "Amtliche Bevölkerungszahlen". Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW (in German). 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Landesbetrieb Information und Technik Nordrhein-Westfalen (IT.NRW), Kommunalprofil Erkelenz

- ↑ Percentages are rounded off

- ↑ Diercke, Weltatlas, Westermann Verlag, Brunswick 1957, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Debra Zizkat and Hans-Wilhelm Cuber, Cusanus Gymnasium Erkelenz, Wetterstation Erkelenz/Haus Hohenbusch,

- ↑ Hans Frohnhofen, Mergeln im Lövenicher Feld in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz 1959, p. 18 ff.

- ↑ Martin Bünermann; Heinz Köstering (1975) (in German), Die Gemeinden and Kreise nach der kommunalen Gebietsreform in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Cologne: Deutscher municipality ofverlag, ISBN 3-555-30092-X

- ↑ "Gliederung der Stadt". Stadt Erkelenz. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ Jürgen Driehaus, Die urgeschichtliche Zeit im Landkreis Erkelenz, in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz 1967, pp. 105 ff.

- 1 2 Jürgen Weiner, Eine bandkeramische Siedlung mit Brunnen bei Erkelenz-Kückhoven, in: Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Lande, Vol. 12, Erkelenz 1992, pp. 17 ff.

- 1 2 Institut für geschichtliche Landeskunde der Rheinlande an der Universität Bonn, Rheinischer Städteatlas, III Nr. 15, Cologne 1976, p. 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al. Geschichte der Stadt Erkelenz, Erkelenz, 1926, p. 2

- ↑ K. Böhner et al., Früher Kirchenbau im Kreis Heinsberg, Museumsschriften des Kreises Heinsberg Band 8, Heinsberg 1987, pp. 206 ff.

- ↑ Leo Gillessen, Zur Ortsnamen- und Siedlungskunde des Kreises Erkelenz (Part I) in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz 1967, p. 145. Derselbe Zur Ortsnamen- und Siedlungskunde des Kreises Erkelenz (Teil II) in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz 1968, p. 82

- ↑ Paul ter Meer, Ortsnamen des Kreises Erkelenz - Ein Versuch zu ihrer Deutung, Erkelenz 1924, pp. 8 f.

- ↑ Theodor Joseph Lacomblet, Urkundenbuch für die Geschichte des Niederrheins, Düsseldorf 1840, p. 63; Friedel Krings et al., 1000 Jahre Erkelenz, Ein Rückblick auf die 1000-Jahr-Feier, Erkelenz 1967, Vorspann, Kopial der Urkunde aus dem 13. Jahrhundert (at Commons); Theo Schreiber, Erkelenz - eine Stadt im Wandel der Geschichte in: Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Lande, Vol. 12, Erkelenz 1992, pp. 43 ff., weiteres Kopial der Urkunde

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 13 f.

- ↑ Friedel Krings, Zur geldrischen Geschichte der Stadt Erkelenz, in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz 1960, p. 53

- ↑ Friedel Krings, op. cit., p. 54

- ↑ Klaus Flink, Stadtwerdung und Wirtschaftskräfte in Erkelenz, Schriftenreihe der Stadt Erkelenz, Vol. 2, Cologne, 1976, pp. 8 f

- ↑ Severin Corsten, Erkelenz erhält Stadtrechte, in: Studien zur Geschichte der Stadt Erkelenz vom Mittelalter bis zur frühen Neuzeit, Schriftenreihe der Stadt Erkelenz, Vol. 1, Cologne, 1976, pp. 137 ff

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels, et al., op. cit., p. 4

- ↑ Herbert Claessen, Hrsg. Geschichte der Erkelenzer Lande, Aus einem Vortag des Landrates Claessen im Jahre 1863, in: Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Lande, Band 20, Erkelenz 2006, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th edition, Vol. 7, Leipzig and Vienna, 1890, pp. 52 f.

- ↑ Friedel Krings, op. cit., p. 55

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., p. 10

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., loco citato pp. 7 ff.

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., p. 154.

- ↑ Friedel Krings, Die mittelalterlichen Befestigungswerke der Stadt Erkelenz, in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz 1957, p. 57

- ↑ Institut für geschichtliche Landeskunde der Rheinlande an der Universität Bonn, Rheinischer Städteatlas, III No. 15, Cologne, 1976, p. 3

- ↑ Friedel Krings op. cit., p. 56

- ↑ Edwin Pinzek, in: Bedeutende Bau- und Kunstwerke in Erkelenz, eine Reihe der Stadt Erkelenz

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Institut für geschichtliche Landeskunde der Rheinlande an der Universität Bonn, Rheinischer Städteatlas, III No. 15, Cologne, 1976, p. 4

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pages 4 ff, 104

- ↑ Herbert Claessen, op. cit., p. 92

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 5 f.

- ↑ Herbert Claessen, op. cit., pp. 93 ff.

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 6 f

- ↑ Herbert Claessen, Weltgeschichte zu Gast in Erkelenz, in: Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Lande, Vol. 20, Erkelenz, 2006, pp. 144 f.

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al. Geschichte der Stadt Erkelenz, Erkelenz, 1926, pp. 5

- ↑ Friedel Krings, Zur geldrischen Geschichte der Stadt Erkelenz, in: Heimatkalender der Erkelenzer Lande, Erkelenz, 1960, p. 51

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels u.a., op. cit., p. 155.

- ↑ Friedel Krings, Die mittelalterlichen Befestigungswerke der Stadt Erkelenz, op. cit., pp. 59 f

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 57 ff

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al. op. cit., pp. 73 ff

- ↑ Josef Lennartz, Die Beschwerde des Franz Schaeven and Das Ende der Stadtmauer, Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Lande, Vol. 1, Erkelenz 1981, pp. 20 ff

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels u. a., op. cit. p. 83

- ↑ Josef Lennartz und Theo Görtz, Erkelenzer Straßen, Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Landes, Vol. 3, Erkelenz 1982, pp. 105, 128

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et. al., o. cit. p. 77

- ↑ Josef Lennartz und Theo Görtz, op. cit. p. 66

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et. al., op. cit., pp. 95 ff

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 99, 129

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 96, 101 f.

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp. 99 f

- ↑ Josef Gaspers, Leo Sels et al., op. cit., pp.100 ff

- ↑ W. Frenken et al. in: Der Nationalsozialismus im Kreis Heinsberg, Museumsschriften des Kreises Heinsberg, Vol. 4, Heinsberg 1983, p. 55

- ↑ Josef Lennartz und Theo Görtz, op. cit., pp. 94, 122, 51

- ↑ W. Frenken et al., op. cit., pp. 103 ff, 57 ff, 75 ff

- ↑ Harry Seipolt, „… stammt aus asozialer und erbkranker Sippe". Zwangssterilisation und NS-Euthanasie im Kreis Heinsberg 1933–1945, in: Heimatkalender des Kreises Heinsberg, 1992, pp. 112 ff.

- ↑ W. Frenken et al., op. cit., pp. 93 ff.

- ↑ W. Frenken et al., op. cit., p. 96

- ↑ Jack Schiefer, Tagebuch eines Wehrunwürdigen, Grenzland-Verlag Heinrich Hollands, Aachen 1947, p. 110; Schriften des Heimatvereins der Erkelenzer Lande, Vol. 12, Erkelenz 1992, p. 229

- ↑ W. Frenken et al., op. cit., p. 98

- ↑ Jack Schiefer, op. cit., pp. 301 f.; op. cit., p. 236

- ↑ Jack Schiefer, Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau im Kreise Erkelenz, Grenzland-Verlag Heinrich Hollands, Aachen 1948, pp. 8 ff., 17 ff., 153 f.

- ↑ Josef Lennartz, Als Erkelenz in Trümmer sank, Stadt Erkelenz 1975, pp. 4 ff., 52 ff., 102 ff.

- ↑ Jack Schiefer, op. cit., pp. 24 ff, 49 f

External links

- Official site

- Photos and information (German)

- Firebrigade museum (German)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erkelenz. |