Nauruan language

| Nauruan | |

|---|---|

| Dorerin Naoero | |

| Native to | Nauru |

| Ethnicity | Nauruan people |

Native speakers |

(6,000, decreasing cited 1991)[1] L2 speakers: perhaps 1,000? (1991)[2][3] |

| Official status | |

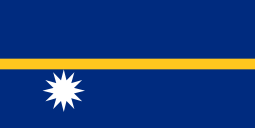

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

na |

| ISO 639-2 |

nau |

| ISO 639-3 |

nau |

| Glottolog |

naur1243[4] |

The Nauruan language (Nauruan: dorerin Naoero) is an Oceanic language, spoken natively by around 6,000 people in the island country of Nauru. Its relationship to the other Micronesian languages is not well understood.

Phonology

Consonants

Nauruan has 16–17 consonant phonemes. Nauruan makes phonemic contrasts between velarized and palatalized labial consonants. Velarization is not apparent before long back vowels and palatalization is not apparent before non-low front vowels.[5]

| Bilabial | Dental | Dorsal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| palatalized | velarized | Palatal | post-velar | labial | |||

| Nasal | mʲ | mˠ | n | ŋ | (ŋʷ) | ||

| Stop | voiceless | pʲ | pˠ | t | k | kʷ | |

| voiced | bʲ | bˠ | d | ɡ | ɡʷ | ||

| Approximant | ʝ | ɣʷ | |||||

| Rhotic | r rʲ | ||||||

Voiceless stops are geminated and nasals also contrast in length.[7] Dental stops /t/ and /d/ become [tʃ] and [dʒ] respectively before high front vowels.[8]

The approximants become fricatives in "emphatic pronunciation." Nathan (1974) transcribes them as ⟨j⟩ and ⟨w⟩ but also remarks that they contrast with the non-syllabic allophones of the high vowels.

Depending on stress, /r/ may be a flap or a trill. The precise phonetic nature of /rʲ/ is unknown. Nathan (1974) transcribes it as ⟨r̵⟩ and speculates that it may pattern like palatalized consonants and be partially devoiced.

Between a vowel and word-final /mˠ/, an epenthetical [b] appears.[5]

Vowels

There are 12 phonemic vowels (six long, six short). In addition to the allophony in the following table from Nathan (1974), a number of vowels reduce to [ə]:[6]

| Phoneme | Allophones | Phoneme | Allophones |

|---|---|---|---|

| /ii/ | [iː] | /uu/ | [ɨː ~ uː] |

| /i/ | [ɪ ~ ɨ] | /u/ | [ɨ ~ u] |

| /ee/ | [eː ~ ɛː] | /oo/ | [oː ~ ʌ(ː) ~ ɔ(ː)] |

| /e/ | [ɛ ~ ʌ] | /o/ | [ʌ] |

| /aa/ | [æː] | /ɑɑ/ | [ɑː] |

| /a/ | [æ ~ ɑ] | /ɑ/ | [ɑ ~ ʌ] |

Non-open vowels (that is, all but /aa/, /a/, /ɑɑ/ /ɑ/) become non-syllabic when preceding another vowel, as in /e-oeeoun/ → [ɛ̃õ̯ɛ̃õ̯ʊn] ('hide').[9]

Stress

Stress is on the penultimate syllable when the final syllable ends in a vowel, on the last syllable when it ends in a consonant, and initial with reduplications.[6]

Writing system

In the Nauruan written language, 17 letters were originally used:

- The five vowels: a, e, i, o, u

- Twelve consonants: b, d, g, j, k, m, n, p, q, r, t, w

The letters c, f, h, l, s, v, x, y and z were not included. With the growing influence of foreign languages (most of all German, Tok Pisin and Kiribati) more letters were incorporated into the Nauruan alphabet. In addition, phonetic differences of a few vowels arose, so that umlauts and other similar-sounding sounds were indicated with a tilde.

Attempt at language reform of 1938

In 1938 there was an attempt by the Nauruan language committee and Timothy Detudamo to make the language easier to read for Europeans and Americans. It was intended to introduce as many diacritical symbols as possible for the different vowel sounds to state the variety of the Nauruan language in writing. It was decided to introduce only a grave accent in the place of the former tilde, so that the umlauts "õ" and "ũ" were replaced by "ò" and "ù". The "ã" was substituted with "e".

Also, "y" was introduced in order to differentiate words with the English "j" (puji). Thus, words like ijeiji were changed to iyeyi. In addition, "ñ" (which represented the velar nasal) was replaced with "ng", to differentiate the Spanish Ñ, "bu" and "qu" were replaced with "bw" and "kw" respectively, "ts" was replaced with "j" (since it represented a pronunciation similar to English "j"), and the "w" written at the end of words was removed.

These reforms were only partly carried out: the umlauts "õ" and "ũ" are still written with tildes. However, the letters "ã" and "ñ" are now only seldom used, being replaced with "e" and "ng", as prescribed by the reform. Likewise, the writing of the double consonants "bw" and "kw" has been implemented. Although the "j" took the place of "ts", certain spellings still use "ts." For example, the districts Baiti and Ijuw (according to the reform Beiji and Iyu) are still written with the old writing style. The "y" has largely become generally accepted.

Today the following 29 Latin letters are used.

- Vowels: a, ã, e, i, o, õ, u, ũ

- Semivowels: j

- Consonants: b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, ñ, p, q, r, s, t, w, y, z

Dialects

According to a report published in 1937 in Sydney, there was a diversity of dialects until Nauru became a colony of Germany in 1888, and until the introduction of publication of the first texts written in Nauruan. The variations were largely so different that people of various districts often had problems understanding each other completely. With the increasing influence of foreign languages and the increase of Nauruan texts, the dialects blended into a standardized language, which was promoted through dictionaries and translations by Alois Kayser and Philip Delaporte.

Today there is significantly less dialectal variation. In the district of Yaren and the surrounding area there is an eponymous dialect spoken, which is only slightly different.

Delaporte's Nauruan Dictionary

In 1907, Philip Delaporte published his pocket German-Nauruan dictionary. The dictionary is small (10.5 × 14 cm), with 65 pages devoted to the glossary and an additional dozen to phrases, arranged alphabetically by the German. Approximately 1650 German words are glossed in Nauruan, often by phrases or synonymous forms. There are some 1300 'unique' Nauruan forms in the glosses, including all those occurring in phrases, ignoring diacritical marks. The accents used there are not common; just one accent (the tilde) is in use today.

Sample text

The following example of text is from the Bible (Genesis, 1.1–1.8):

1Ñaga ã eitsiõk õrig imim, Gott õrig ianweron me eb. 2Me eitsiõk erig imin ñana bain eat eb, me eko õañan, mi itũr emek animwet ijited, ma Anin Gott õmakamakur animwet ebõk. 3Me Gott ũge, Enim eaõ, me eaõen. 4Me Gott ãt iaõ bwo omo, me Gott õekae iaõ mi itũr. 5Me Gott eij eget iaõ bwa Aran, me E ij eget itũr bwa Anũbũmin. Ma antsiemerin ma antsioran ar eken ũrõr adamonit ibũm. 6Me Gott ũge, Enim tsinime firmament inimaget ebõk, me enim ekae ebõk atsin eat ebõk. 7Me Gott eririñ firmament, mõ õ ekae ebõk ñea ijõñin firmament atsin eat ebõk ñea itũgain firmament, mõ ũgan. 8Me Gott eij egen firmament bwe Ianweron. Ma antsiemerin ma antsioran ar eke ũrõr karabũmit ibũm.

It is notable that the Nauruan vocabulary contains a few German loanwords (e.g. Gott, God; and Firmament, celestial sphere), which is traced back to the strong influence of German missionaries. There are also Latin loanwords such as "õrig" (from Lat. origo, beginning) that appear.

Phrases

| Nauruan | English |

|---|---|

| Anubumin | Night |

| Aran | Day |

| Bagadugu | Ancestors |

| (E)kamawir Omo | Best wishes |

| Ebok | Water |

| Firmament | Earth; celestial sphere |

| Gott | God |

| Ianweron | Heaven |

| Iao | Light |

| Iow | Peace |

| Itur | Darkness |

| Orig | Beginning |

| Tarawong (ka) | Goodbye |

References

- ↑ Nauruan at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Probably unreliable. The number is the difference of two population estimates, which may have used different criteria or were based on data from different dates.

- ↑ Nauruan language at Ethnologue (14th ed., 2000).

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Nauru". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 Nathan (1974:481)

- 1 2 3 Nathan (1974:483)

- ↑ Nathan (1974:481–483)

- ↑ Nathan (1974:481–482)

- ↑ Nathan (1974:482)

Bibliography

- "Nauru Grammar", by Alois Kayser compiled (1936); distributed by the German embassy 1993, ISBN 0-646-12854-X

- Nathan, Geoffrey S. (1974), "Nauruan in the Austronesian Language Family", Oceanic Linguistics, University of Hawai'i Press, 12 (1/2): 479–501, doi:10.2307/3622864, JSTOR 3622864

External links

| Nauru edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |