Lardil language

| Lardil | |

|---|---|

| Leerdil | |

| Pronunciation | [leːɖɪl] |

| Region | Bentinck Island, north west Mornington Island, Queensland |

Native speakers | 10 (2005) to 50 (2006 census)[1] |

|

Macro-Pama–Nyungan

| |

| Dialects | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

lbz |

| Glottolog |

lard1243[2] |

| AIATSIS[1] |

G38 |

|

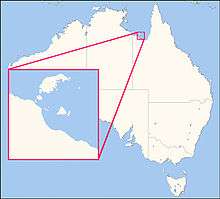

Location of Wellesley Islands, the area traditionally associated with Lardil | |

Lardil (also spelled Leerdil or Leertil) is a moribund language spoken by the Lardil people on Mornington Island (Kunhanha), in the Wellesley Islands of Queensland in northern Australia.[3] Lardil is unusual among Australian languages in that it features a ceremonial register, called Damin (also Demiin). Damin is regarded by Lardil speakers as a separate language, and possesses the only phonological system outside Africa to use click consonants.[4]

Associated languages

Lardil is a member of the Tangkic family of Non-Pama–Nyungan Australian languages, along with Kayardild and Yukulta, which are close enough to be mutually intelligible.[5] Though Lardil is not mutually intelligible with either of these,[6] it is likely that many Lardil speakers were historically bilingual in Yangkaal (a close relative of Kayardild), since the Lardil people have long been in contact with the neighboring Yangkaal tribe and trading, marriage and conflict between them seem to have been common.[7] There was also limited contact with mainland tribes including the Yanyuwa, of Borroloola; and the Garawa and Wanyi, which groups ranged as far east as Burketown.[8] Members of the Kaiadilt tribe (i.e. speakers of Kayardild) also settled on nearby Bentinck Island in 1947.[9]

Outlook

The number of Lardil speakers has diminished dramatically since Kenneth Hale's study of the language in the late 1960s. Hale worked with a few dozen speakers of Lardil, some of these fluent older speakers, and others younger members of the community who had only a working or passive understanding.[10][11] When Norvin Richards, a student of Hale's, returned to Mornington Island to continue work on Lardil in the 1990s, he found Lardil children had no understanding of the language and that only a handful of aging speakers remained;[11] Richards has stated that "Lardil was deliberately destroyed"[11] by assimilation and relocation programs in the years of the "Stolen Generation". A dictionary and grammatical sketch of the language were compiled and published by the Mornington Shire Council in 1997,[12] and the Mornington Island State School has implemented a government-funded cultural education program incorporating the Lardil language.[13] The last fluent speaker of so-called Old Lardil died in 2007,[14] though a few speakers of a grammatically distinct New variety remain.[15]

Kinship terms

Lardil has an intensely complex system of kinship terms reflecting the centrality of kin-relations to Lardil society; all members of the community are addressed by the terms as well as by given names.[16] This system also features a few dyadic kinship terms, i.e. titles for pairs rather than individuals, such as kangkariwarr ‘pair of people, one of whom is the paternal great uncle/aunt or grandparent of the other’.[17]

| Title | Relation(s) |

|---|---|

| kangkar | FaFa, FaFaBr, FaFaSi |

| kantha | Fa, FaBr |

| babe | FaMo, FaMoSi, FaMoBr |

| jembe | MoFa, MoFaBr, MoFaSi |

| nyerre | MoMo, MoMoBro, MoMoBrSoCh |

| merrka | FaSi |

| wuyinjin | WiFa, HuFa, FaFaSiSo, FaMoBrSo |

| ngama | Mo, MoSi, SoWi, BrSoWi |

| kunawun | WiMo, WiMoBr |

| yaku | MoBrDaDa, sister (male ego), elder sister (female ego) |

| kambin | Ch, BrCh (both male ego) |

| karda | Ch, SiCh, WiFaSi, MoMoMo(and siblings) (all female ego) |

| kernde | Wi, WiSi, ‘second cross-cousin’ |

| kangkur | SoSo, SoDa (both male ego); BrSoSo, BrSoDa (both female ego) |

| nginngin | SoCh (female ego), SiSoCh (male ego) |

| benyin | DaSo, DaDa |

Initiate languages

Traditionally, the Lardil community held two initiation ceremonies for young men. Luruku, which involved circumcision, was undergone by all men following the appearance of facial hair;[18] warama, the second initiation, was purely voluntary and culminated in a subincision ceremony.[19]

Luruku initiates took a year-long oath of silence and were taught a sign language known as marlda kangka (literally, ‘hand language’), which, though limited in its semantic scope, was fairly complex.[20] Anthropologist David McKnight's research in the 1990s suggests that marlda kangka classifies animals somewhat differently from Lardil, having, for example, a class containing all shellfish (which Lardil lacks) and lacking an inclusive sign for ‘dugong+turtle’ (Lardil dilmirrur).[17] In addition to its use by luruku initiates, marlda kangka had practical applications in hunting and warfare.[21]

While marlda kangka was essentially a male language, the non-initiated were not forbidden to speak it.[21] Damin, on the other hand, was (at least nominally) a secret language spoken only by warama initiates and those preparing for second initiation,[4] though many community members seem to have understood it.[22] Damin, like marlda kangka, was phonologically, lexically and semantically distinct from Lardil, though its syntax and morphology seem to be analogous.[23] Research into the language has proved controversial, since the Lardil community regards it as cultural property and no explicit permission was given to make Damin words public.[22]

Necronyms

Death in Lardil tends to be treated euphemistically; it is common, for example, to use the phrase wurdal yarburr ‘meat’ when referring to a deceased person (or corpse).[17] Yuur-kirnee yarburr (literally, ‘The meat/animal has died’) has the sense ‘You-know-who has died’, and is preferable to a more direct treatment.[17] It is taboo to speak the name of a deceased person, even (for a year or so) when referring to living people with the same name; these people are addressed as thamarrka.[24] The deceased is often known by the name of his/her death or burial place plus the ‘necronym’ suffix -ngalin, as in Wurdungalin ‘one who died at Wurdu’.[24] Sometimes other strategies are used to refer to the dead, such as circumlocution via kinship terms.[24]

Phonology

Consonants

The consonant inventory is as follows, with the practical orthography in parentheses.

| Peripheral | Laminal | Apical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Velar | Palatal | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | |

| Plosive | p (b) | k (k) | tʲ (j) | t̪ (th) | t (d) | ʈ (rd) |

| Nasal | m (m) | ŋ (ng) | ɲ (ny) | n̪ (nh) | n (n) | ɳ (rn) |

| Trill or flap | r (rr) | |||||

| Lateral | ʎ (ly) | l (l) | ɭ (rl) | |||

| Approximant | w (w) | j (y) | ɻ (r) | |||

Lardil's consonant inventory is fairly typical with respect to Australian phonology; it does not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced stops (such as b/p and g/k), and features a full set of stops and nasals at six places of articulation [25] The distinction between ‘apical’ and ‘laminal’ consonants lies in whether the tip (apex) of the tongue or its flattened blade makes contact with the place of articulation.[22] Hale's 1997 practical orthography has ‘k’ for /k ~ ɡ/ in order to disambiguate nasal+velar clusters (as in wanka ‘arm’[26]) from instances of the velar nasal phoneme /ŋ/ (as in wangal ‘boomerang’[26]) and to avoid suggesting /ɡ/-gemination in /ŋ + k~ɡ/ clusters (as in ngangkirr ‘together’[26]). The sounds represented by the digraphs ‘nh’ and ‘ly’ are not common in Lardil, but speakers perceive them as distinct, respectively, from /n/ and /l/, and they do occur in some words (e.g. minhal ‘burnt ground’, balyarriny [title of a social subsection]).[27]

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i iː (ii) | u uː (uu) |

| Mid | e eː (ee) | |

| Low | a aː (aa) |

Lardil has eight phonemically distinct vowels, differentiated by short and long variants at each of four places of articulation.[28] Phonemic vowel length is an important feature of many Australian languages; minimal pairs in Lardil with a vowel length distinction include waaka/waka ‘crow’/’armpit’ and thaldi/thaldii ‘come here!’/’to stand up’.[26] Long vowels are roughly twice as long as their short counterparts.[28]

Stress

Primary word stress in Lardil falls on the initial syllable, and primary phrase stress on the final word in the phrase.[29] These stress rules have some exceptions, notably compounds containing tangka ‘man’ as a head noun modified by a demonstrative or another nominal; these expressions, and other compound phrases, have phrase-initial stress.[30]

Phonotactics

Common alternations (consonants)

- /rr ~ d/, _#

- The distinction between /rr/ and /d/ is lost word-finally, as in yarburr ‘bird/snake’, which may be realized as [yarburr] or [yarbud], depending on the instance.[31]

- /d ~ n, j ~ ny/, _N

- /d/ and /j/ may assimilate to a following nasal, as in bidngen > binngen ‘woman’, or yuujmen > yuunymen ‘oldtime’.[31]

- /r ~ l/, #_

- Word-initial /r/ is often expressed as /l/; as with /rr ~ d/, either (e.g.) [leman] or [reman] may be heard for ‘mouth’.[31]

Word-final phonology

In addition to the common phonological alterations noted above, Lardil features some complex word-final phonology which is affected by both morphological and lexical factors.[32]

Augmentation acts on many monomoraic forms, producing, for example, /ʈera/ 'thigh' from underlying *ter.[32]

High vowels tend to undergo lowering at the end of bimoraic forms, as in *penki > penke 'lagoon'.[32] In several historical locative/ergatives, lowering does not occur.[32] It does occur in at least one long, u-final stem, and it coexists with the raising of certain stem-final /a/s.[32]

In some trimoraic (or longer) forms, final, underlying short vowels undergo apocope (deletion), as in *jalulu > jalul 'fire'.[32] Front-vowel apocope fails to occur in locatives, verbal negatives, many historical locative/ergatives, and a number of i-final stems such as wan̪t̪alŋi 'a species of fish'.[32] Back-vowel apocope also has lexically-governed exceptions.[22]

Cluster reduction simplifies underlying word-final consonant clusters, as in *makark > makar 'anthill'.[32] This process is "fed" in a sense by apocope, since some forms that would otherwise end in a short vowel arise as cluster-final after apocope (e.g. *jukarpa > *jukarp > jukar 'husband').[32]

Non-apical truncation results in forms like ŋalu from underlying *ŋaluk, in which the underlying form would end in a non-apical consonant (i.e. one not produced with the tip of the tongue).[32] This process is also fed by apocope, and seems to be lexically governed to an extent, since Lardil words can end in a laminal; compare kakawuɲ 'a species of bird', kulkic 'a species of shark'.[32]

In addition to the dropping of non-apicals, a process of apicalization is at work, giving forms such as ŋawit from underlying laminal-final *ŋawic. It has been proposed that the process responsible for some of these forms is better described as laminalization (i.e. nawit is underlying and nawic occurs in inflected forms), but apicalization explains the variation between alveolar /t/ and dental /t̪/ (contrastive but both apical) in surface forms with an underlying non-apical, and does not predict/generate as many invalid forms as does the laminalization model.[32]

Grammar

Parts of speech

Verbs

The first major lexical class in Lardil is its verbs, which may be subclassified as intransitive, transitive, and intransitive- and transitive complemented.[33] Verbs are both semantically and (as discussed below), morphologically distinct from nominals.[34]

Nominals

Nominals are a semantically and functionally diverse group of inflected items in Lardil. Some of them are 'canonical nouns' which refer to items, people or concepts;[33] but many, the stative or attributive nominals, are semantically more like adjectives or other predicates.[33] Kurndakurn 'dry', durde 'weak', and other lexical items with adjectival meanings inflect exactly like other nominals[35] Determiners (e.g. nganikin 'that', baldu(u)rr 'that (distant) west'[17]), are also morphological nominals, as are inherently temporal and spatial adverbs[34] (e.g. dilanthaarr 'long ago', bada 'in the west'[17]).

Pronouns

Lardil has a rich pronominal system featuring an inclusive-exclusive plurality distinction, a dual number and generational harmony.[36]

A ‘harmonic’ relationship exists between individuals of alternate generations (e.g. grandparent /grandchild); a ‘disharmonic’ relation is between individuals of consecutive or odd-numbered generations (e.g. parent/child, great-grandparent/great-grandchild).[37]

| Harmonic | Disharmonic | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ngada | |

| 2 | nyingki | |

| 3 | niya | |

| 1du exc. (11) | nyarri | nyaan |

| 1du inc. (12) | ngakurri | ngakuni |

| 2du (22) | kirri | nyiinki |

| 3du (33) | birri | nyiinki |

| 1P exc. (111) | nyali | nyalmu |

| 1P inc. (122) | ngakuli | ngakulmu |

| 2P (222) | kili | kilmu |

| 3P (333) | bili | bilmu |

Uninflected elements

Uninflected elements in Lardil include:

- Particles, such as nyingkeni ‘completely gone’ or niimi ‘thus, therefore’.[17][39]

- Exclamations, such as may (a guilty plea, roughly) and bardu ‘Gotcha!’ (said when something is offered and then snatched away).[17][39]

- Preverbs, such as bilaa- ‘tomorrow’, and other coverbs.[17][39]

- Enclitics, such as -kili, an optative suffix, as in Manme-kili barnjibarn ‘dry+OPT hat’ = "Let (your hat dry)".[17][39]

Morphology

Verbal morphology

Nine basic inflectional endings appear on verbs in Lardil:

The future marker (-thur) indicates anticipation/expectation of an event, or, when combined with the particle mara, either the proposed outcome of a hypothetical (If you had done X, I would have Y’ed) or an unachieved intention; it also marks embedded verbs in jussive clauses.[40]

The (marked) non-future is used primarily in dependent clauses to indicate a temporal limit to an action.[41]

The contemporaneous ending marks a verb in a subordinate clause when that verb's referent action is contemporaneous with the action described in the main clause.[42]

The evitative ending, which appears as -nymerra in objective (oblique) case, marks a verb whose event or process is undesirable or to be avoided, as in niya merrinymerr ‘He might hear’ (and we don’t want him to); it is somewhat analogous to English ‘lest’, though more productive.[43]

When one imperative follows another closely, the second verb is marked with a Sequential Imperative ending.[44]

Negation is semantically straightforward, but is expressed with a complex set of affixes; which is used depends on other properties of the verb.[45]

Other processes, which may be characterized as derivational rather than inflectional, express duration/repetition, passivity/reflexivity, reciprocality, and causativity on the verb.[46] Likewise, nouns may be derived from verbs by adding the suffix (-n ~ -Vn), as in werne-kebe-n ‘food-gatherer’ or werne-la-an ‘food-spearer’; the negative counterpart of this is (-jarr), as in dangka-be-jarr (man+bite+neg) ‘non-biter-of-people’.[47]

Nominal morphology

Lardil nominals are inflected for objective, locative and genitive cases, as well as future and non-future; these are expressed via endings that attach to the base forms of nominals.

Nominative case

The nominative case, which is used with sentence subjects and objects of simple imperatives (such as yarraman ‘horse’ in Kurri yarraman ‘(You) Look at the horse.’) is not explicitly marked; uninflected nouns carry nominative case by default.[48]

Objective (oblique) case

The objective case (-n ~ -in) has five general functions, marking (1) the object of a verb in plain (i.e. unmarked non-future) form, (2) the agent of a passive verb in plain form, (3) the subject of a contemporaneous dependent clause (i.e. a 'while'/'when' clause), (4) the locative complement of a verb in the plain negative or negative imperative, and (5) the object of the sequential imperative (see section on verb morphology above).[34] Lardil displays some irregularities in object-marking morphology.[48]

Locative case

The locative marker (-nge ~ -e ~ -Vː) appears on the locative complement of a verb in plain form.[49] The objective case serves this purpose with negative verbs.[49] Locative case is formed by lengthening the final vowel in instances of vowel-final base forms such as barnga ‘stone’ (LOC barngaa).[49] While the Locative case can denote a variety of locative relations (such as those expressed in English by at, on, in, along, etc.), such relations may be specified using inherently locative nominals (e.g. minda ‘near’, nyirriri ‘under’) that do not themselves inflect for this case. Nominals corresponding to animate beings tend not to be marked with Locative case; Genitive is preferred for such constructions as yarramangan ‘on the horse’ (lit. ‘of the horse’). On pronouns, for which case-marking is irregular, Locative case is realized via ‘double-expression’ of Genitive case: ngada ‘I’ > ngithun ‘I(gen) = my’ > ngithunngan ‘I(gen)+gen = on me’.[49]

Genitive case

The genitive morpheme (-kan ~ -ngan) marks (1) a possessor nominal, (2) the agent of a passive verb in the future, non-future or evitative; (3) the pronominal agent of any passive verb, (4) the subject of a relative clause, if it is a non-subject in the sentence; and (5) the subject of a cleft construction in which the topic is a non-subject (e.g. Diin wangal, ngithun thabuji-kan kubaritharrku ‘This boomerang, my brother made.’).[50]

Future

The object of a verb in future tense (either negative or affirmative) is marked for futurity[51] by a suffix (-kur ~ -ur ~ -r), as in the sentence below:

| (1) | Ngada | bulethur | yakur. |

| 1pS (NOM) | catch+FUT | fish+FUT | |

| 'I will catch a fish.' | |||

The future marker also has four other functions. It marks: (a) the locative complement (‘into the house’, ‘on the stone’) of a future verb, (2) the object of a verb in contemporaneous form, (3) the object of a verb in the evitative form (often translated as ‘be liable to V’, ‘might V’), and (4) the dative complement of certain verbs (e.g. ngukur ‘for-water’ in Lewurda ngukur ‘Ask him for water’). The instrumental case inflection is homophonous with the future marker, but both may appear on the same nominal in certain instances.[52]

Non-future

The object of a verb in the (negative or affirmative) marked non-future also inflects for non-futurity. The non-future marking (-ngarr ~ -nga ~ -arr ~ -a) is also used to mark time adverbials in non-future clauses as well as the locative complement of a non-future verb.[53]

Verbal case

In addition to these inflectional endings, Lardil features several morphologically verbal affixes that are semantically similar to case markers ("verbal case") and, like case endings, mark noun phrases rather than individual nouns. Allative and ablative meanings (i.e. movement to or from) are expressed with these endings; as are the desiderative and a second type of evitave; comitative, proprietive and privative.[54]

Verbalizing suffixes

Lardil nominals may also take one of two derivational (verbalizing) suffixes: the Inchoative (-e ~ -a ~ -ya), which has the sense ‘become X’, and the Causative (-ri ~ -iri), which has the sense ‘make X Y’; other verbalizing suffixes exist in Lardil but are far less productive than these two.[55]

Reduplication

Reduplication is productive in verbal morphology, giving a non-future durative with the pattern V-tharr V (where V is a verb), having the sense 'keep on V-ing', and a future durative with V-thururr V-thur.[44]

In some instances nominal roots may be reduplicated, in their entirety, to indicate plurality, but Lardil nominals are not generally marked for number and this form is fairly rare.[56]

Syntax

Given the rich morphology of Lardil, it is not surprising that its word order is somewhat flexible; however, the basic sentence order has been described as SVO, with direct object either following or preceding indirect object and other dependents following these.[57] Clitics appear clause-second and/or on either side of the verb.[57]

Syntax and case assignment

Lardil is unique among the Tangkic languages in being non-ergative.[57] In an ergative language, the subject of an intransitive verb takes nominative case while the subject of a transitive verb takes ergative case (the object of this verb takes nominative case). In Lardil, subjects of both verb types are inflected for nominative case, and both indirect and direct objects marked for accusative[57] as in the following sentences:

| (1) | Ngada | kudi | kun | yaramanin |

| 1pS (NOM) | see | EV | horse+AC | |

| 'I saw a horse.'[57] | ||||

| (2) | Pidngen | wutha | kun | ngimpeen | tiin | midithinin |

| woman+NOM | give | EV | 2pS(AC) | this+AC | medicine+AC | |

| 'The woman gave you this medicine.'[57] | ||||||

Kun, glossed as ‘EV’, is an eventive marker, marking a verb referring to something that actually occurred or is occurring.

Subjects (i.e. patients) of passive verbs also take nominative case, and their objects (i.e. agents), take accusative,[58] as in:

| (3) | Ngithun | wangal | yuud | wuungii | tangan |

| 1pS (AC) | boomerang+AC | PERF | steal+R | man+AC | |

| 'My boomerang was stolen by a man.'[58] | |||||

Here, R is a maker of reflexivity.

Part-whole compounds

Though part-whole relations are sometimes expressed using the genitive case as in (1) below, it is more common to mark both part and whole with the same case, placing the ‘part’ nominal immediately after its possessor nominal, as in (2).[59]

| (1) | bidngenngan | lelka | |

| woman+GEN | head(NOM) | ||

| 'the woman's head'[59] | |||

| (2) | Ngada | yuud-latha | karnjinin | lelkin |

| 1pS(NOM) | PERF+spear | wallaby+OBJ | head+OBJ | |

| 'I speared the wallaby in the head.' (lit. 'I speared the wallaby head')[59] | ||||

New Lardil

While very few speakers of Lardil in its traditional form remain, Norvin Richards and Kenneth Hale both worked with some speakers of a "New Lardil" in the 1990s which displays significant morphological attrition compared to the Old variety.[60][61] Previously minor sentence forms in which the object of a verb takes nominative case have become generalized, even in instances where the verb is in future tense (objects of future verbs historically inflected for futurity).[60] One of a number of negation patterns has become generalized, and the augmented forms of monosyllabic verb roots reinterpreted as base forms.[62]

References

- 1 2 Lardil at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Lardil". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 3

- 1 2 McKnight 1999, 26

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 3-6

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 4

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 5

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 3-5

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 3-4

- ↑ Hale 1997, 54

- 1 2 3 http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2003/richards-1022.html

- ↑ Leman 1997, 2

- ↑ Mornington Island State School

- ↑ http://www.ogmios.org/ogmios_files/338.htm

- ↑ http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2003/richards-1022.html and Richards 1997

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 33

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Leman 1997

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 22

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 25

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 24 and 157

- 1 2 McKnight 1999, 158

- 1 2 3 4 Round 2011

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 26 and Round 2011

- 1 2 3 McKnight 1999, 68

- ↑ Klokeid 1976, 16

- 1 2 3 4 Leman 1999

- ↑ Hale 1997, 15, 16

- 1 2 Hale 1997, 18

- ↑ Klokeid 1976, 29

- ↑ Klokeid 1976, 29-30

- 1 2 3 Hale 1997, 17

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Round forthc. 2011

- 1 2 3 Hale 1997, 51

- 1 2 3 Hale 1997

- ↑ .Hale 1997, 52

- ↑ Hale 1997, 53 and Klokeid 1976 108-110

- ↑ McKnight 1999, 41-43

- ↑ Hale 1997 and Klokeid 1976

- 1 2 3 4 Hale 1997, 52

- ↑ Hale 1997, 24

- ↑ Hale 1997, 25

- ↑ Hale 1997, 27

- ↑ Hale 1997, 27-28

- 1 2 Hale 1997, 29

- ↑ Hale 1997, 28

- ↑ Hale 1997, 29-31

- ↑ Hale 1997, 31

- 1 2 Hale 1997, 34

- 1 2 3 4 Hale 1997, 41-43

- ↑ Hale 1997, 43

- ↑ Hale 1997, 36

- ↑ Hale 1997, 36-39

- ↑ Hale 1997, 39-41

- ↑ Hale 1997, 46-50

- ↑ Hale 1997, 50-51

- ↑ Klokeid 1976, 66

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Klokeid 1976, 9

- 1 2 Klokeid 1976, 274

- 1 2 3 Hale 1997, 45

- 1 2 Hale 1997, 54-56 (appendix)

- ↑ Wright 2003

- ↑ Hale 1997, 56 (appendix)

Sources

- Bowern, Claire and Erich Round. Lectures on Australian Aboriginal languages. Spring 2011. Yale University.

- Klokeid, Terry J. 1976. Topics in Lardil Grammar

- McKnight, D. 1999. People, Countries and the Rainbow Serpent.

- "Mornington Island State School". Retrieved April 2011

- Ngakulmungan Kangka Leman and K.L. Hale. 1997. Lardil dictionary : a vocabulary of the language of the Lardil people, Mornington Island, Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland: with English-Lardil finder list. Gununa, Qld, Mornington Shire Council. ISBN 0-646-29052-5

- Richards, Norvin. Leerdil Yuujmen bana Yanangarr (Old and New Lardil). MIT, 1997.

- Round, Erich. Lecture on Kayardild and related languages. 4/7/2011, Yale University.

- Round, Erich R. 2011 (forthcoming). Word final phonology in Lardil: Implications of an expanded data set. Australian Journal of Linguistics.

- Wright, Sarah H. 2003. "Professor brings Aboriginal language to life". in MIT News, 22 October 2003. Retrieved April 2011.

Further reading

- Dixon, R. M. W. 1980. The Languages of Australia.

- Evans, Nicholas (with Paul Memmott and Robin Horsman). 1990. Chapter 16: Travel and communication. In P. Memmott & R. Horsman, A changing culture. The Lardil Aborigines of Mornington Island. Social Sciences Press, Wentworth Falls, NSW.

- Hale, Kenneth L. 1967. Some Productive Rules in Lardil (Mornington Island) Syntax, pp. 63–73 in Papers in Australian Linguistics No. 2, ed. by C.G. von Brandenstein, A. Capell, and K. Hale. Pacific Linguistics Series A, No. 11.

- Hale, Kenneth L. . 1973. Deep-Surface Canonical Disparities in Relation to Analysis and Change.

- Hale, Kenneth L. and D. Nash. 1997. Damin and Lardil Phonotactics.

- Memmott, P., N. Evans and R. Robinsi Understanding Isolation and Change in Island Human Population though a study of Indigenous Cultural Patterns in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

- Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2005. "Lardil syllable structure and stray erasure".