History of Oklahoma

The history of Oklahoma refers to the history of the state of Oklahoma and the land that the state now occupies. Areas of Oklahoma east of its panhandle were acquired in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, while the Panhandle was not acquired until the U.S. land acquisitions following the Mexican–American War.

Most of Oklahoma was set aside as Indian Territory before the Civil War. It was opened for general settlement around 1890—the "Sooners" were settlers who jumped the gun. Statehood came to the poor ranching and farming state in Oklahoma, but soon oil was discovered and new wealth poured in.

Historians David Baird and Danny Goble have searched for the essence of the historical experiences of the people of Oklahoma. They find that, "The shared experiences of Oklahoma's people over time speak of optimism, innovation, perseverance, entrepreneurialism, common sense, collective courage, and simple decency. Those, not victimization, were the core values."[1]

Before statehood

Topographically, Oklahoma is situated between the Great Plains and the Ozark Plateau in the Gulf of Mexico watershed. [2] The western part of the state is subjected to extended periods of drought and high winds in the region may then generate Dust storms. The eastern part of the state is humid subtropical climate zone. The Dry line, an imaginary line that separates moist air from an eastern body of water and dry desert air from the west, usually bisects the state and is arguably an important factor in pre-historic settlement, with agrarian tribes settling in the eastern part of the state and Hunter-gatherer tribes settling in the western part of the state.

Before 1500 AD

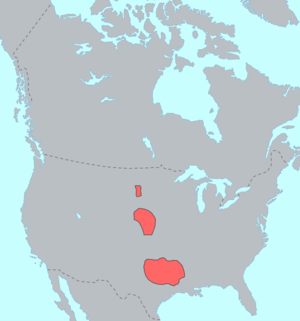

Modern day man has been in Oklahoma as long as the oldest known documented paleo cultures in the field of archaeology/anthropology. From the oldest projectile points of the Clovis Culture to the highly advanced Folsom and breaking off down into the lesser known cultures whose artifacts and kill sites have been well documented all over the state (Dalton, Midland, HellGap, Alberta/Scottsbluff, Calf Creek), the Homo sapiens race was present and very active in what is now today known as the State of Oklahoma. During the first "officially" documented exploration undertaken by Spanish Conquistador Hernando de Soto the indigenous peoples that populated the pan-shaped landlocked state were part of a larger cultural group called Plains Caddoan. The Caddoan languages are a family of languages including those spoken by the Caddo, Wichita, Pawnee, and Kichai peoples.

The Caddoan Mississippi Culture

Between 1000 and 1600 AD, much of the midwestern and southeastern US (including the eastern part of what is now Oklahoma) was home to a group of dynamic cultural communities that are generally known as the Mississippian culture. These cultures were agrarian, their communities often built ceremonial platform and burial mounds, and trade between communities was based on river travel. There were multiple chiefdoms that never controlled large areas or lasted more than a few hundred years.[3]

The Caddoan Mississippian culture appears to have emerged from earlier groups of Woodland period groups, the Fourche Maline and Mossy Grove culture peoples who were living in the area around 200 BC to 800 AD.[4] By 800 AD early Caddoan society had began to coalesce into one of the earlier Mississippian cultures. Some villages began to gain prominence as ritual centers, with elite residences and platform mound constructions. The mounds were arranged around open plazas, which were usually kept swept clean and were often used for ceremonial occasions. The Caddoan homeland was on the geographical and cultural edge of the Mississippian world and had similarities to both Mississippian Culture and Plains Traditions. The Caddoan communities were not as large as other eastern and southern Mississippian communities, they were not fortified, and they did not establish large, complex chiefdoms; with the possible exception of the Spiro Mounds on the Arkansas River. As complex religious and social ideas developed, some people and family lineages gained prominence over others. This hierarchical structure is marked in the archaeological record by the appearance of large tombs with exotic grave offerings of obvious symbols of authority and prestige, such as those found in the "Great Mortuary" at Spiro.[4][5]

Wichita Plains Culture

Archaeologists believe that ancestors of the Wichita people occupied the eastern Great Plains from the Red River north to Nebraska for at least 2,000 years.[6] These early Wichita people were hunters and gatherers who slowly adopted agriculture. About 900 AD, on terraces above the Washita and South Canadian Rivers in Oklahoma, farming villages began to appear. The inhabitants of these villages grew corn, beans, squash, marsh elder, and tobacco. They hunted deer, rabbit, turkey, and increasingly bison, and caught fish and collected mussels in the rivers. These villagers lived in rectangular thatched houses.[7] They became numerous, with villages of up to 20 houses spaced every two or so miles along the rivers.[8]

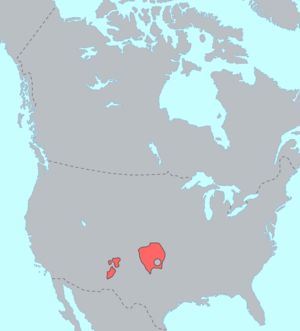

By 1500, Apache groups had also begun moving into formerly Wichita areas of Oklahoma. However, it appears that the two people co-existed in the region for some time. In addition to Apache influence, the Wichita of southwestern Oklahoma appear to have had regular trade contact with tribes in current Texas and New Mexico.[9]

Kiowa-Apache Culture

In historic times, the Kiowa and Apache have a history that is closely related. Both were hunter gatherers who used dogs to carry their belongings as they hunted from place to place. Both seem to have originated thousands of years ago in the Southwest, and migrated north. Then, both migrated from Canada to the Southwest around the time Francisco Coronado explored the Southwest and introduced the horse into the environment. And both tribes adapted their cultures to include the horse.

However, linguistically, they are quite different. The Apache are a Southern Athabaskan group that traditionally live on the Southern Plains of North America. The Kiowa are part of a Tanoan group located in the Pueblos of New Mexico.

The Kiowa language is part of the Kiowa-Tanoan language family. Tanoan languages are those that were spoken in the Jemez, Piro, Tiwa, and Tewa pueblos of New Mexico. Linguists who study the history of languages, however, believe that Kiowa split from Tanoan branch over 3,000 years ago and moved to the far north.[10]

The Kiowa and Apache adopted many of the same lifestyle traits, but remained ethnically distinct. Rather than learning each other's language, they communicated using Plains Indian Sign Language. The Kiowa and Plains Apache lived in the plains adjacent to the Arkansas River in southeastern Colorado and western Kansas and the Red River drainage of the Texas Panhandle and western Oklahoma.[11]

The Kiowas had a well structured tribal government like most tribes on the Northern Plains. They had a yearly Sun Dance gathering and a chieftain who was considered to be the leader of the entire tribe. There were warrior societies and religious societies that made up the Kiowa society.

Historically, the Apache culture seems to have been similar to the Pueblo peoples of the area. However, once the Spanish exercised their power over the area, traditional trade patterns between the tribes was disrupted and the Pueblo were forced to work Spanish mission lands and care for mission flocks. The Pueblo became subsistence laborers; they had fewer surplus goods to trade with their neighbors. The Apache quickly acquired horses, improving their mobility for quick raids on settlements.[12]

Louisiana (New France)

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle claimed all of the Mississippi River and its tributaries for the Kingdom of France. As such, the land that would become Oklahoma was under French control from 1682–1763 as part of the territory of Louisiana (New France). Colonization efforts primarily occurred in the northern aspects (e.g., Illinois) and the Mississippi River valley; Oklahoma would be untouched by French colonial efforts. At the conclusion of the Seven Years' War and its North American counterpart, the French and Indian War, France was forced to cede the eastern part of the territory in 1763 to the British as part of the Treaty of Paris. Interestingly, France had already ceded the entire territory to the Kingdom of Spain in 1762 in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau; the transfer to Spain was not publicly announced until 1764. Spain, which ceded Spanish Florida to the British in the Treaty of Paris in order to regain its colonies in Havana and Manila, did not contest British authority over the eastern part of French Louisiana as it desired the western portion that was adjacent to its colony of New Spain.

Spanish colonization efforts focused on New Orleans and its surroundings, and so Oklahoma remained free from European settlement during Spanish rule. In 1800, France regained sovereignty of the western territory of Louisiana in the secret Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. But, strained by obligations in Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte decided to sell the territory to the United States.

Louisiana Purchase and Arkansas Territory

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States acquired France's 828,000 square mile claim to the watersheds of the Mississippi River (west of the river) and Missouri River. The purchase encompassed all or part of 15 current U.S. states (including all of Oklahoma) and parts of two Canadian provinces.

Out of the Louisiana Purchase, Louisiana Territory and Orleans Territory were organized. Orleans Territory became the state of Louisiana in 1812, and Louisiana Territory was renamed Missouri Territory to avoid confusion.

Arkansas Territory was created out of the southern part of Missouri Territory in 1819. The border was established at parallel 36°30' north with the exception of the Missouri Bootheel. Arkansas Territory thus included all of the present state of Oklahoma south of the this latitude. When Missouri achieved statehood in 1821, the territorial lands not included within the state's boundaries effectively became an unorganized territory. On November 15, 1824, the westernmost portion of Arkansas Territory was removed and included with the unorganized territory to the north, and a second westernmost portion was removed on May 6, 1828, reducing Arkansas Territory to the extent of the present state of Arkansas. This new western border of Arkansas was originally intended to follow the western border of Missouri due south to the Red River. However, during negotiations with the Choctaw in 1820, Andrew Jackson unknowingly ceded more of Arkansas Territory to them than was realized. Then in 1824, after further negotiations, the Choctaw agreed to move farther west, but only by "100 paces" of the garrison on Belle Point. This resulted in the bend in the Arkansas/Oklahoma border at Fort Smith, Arkansas.[13]

The Adams–Onís Treaty and New Spain

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 was between the United States and Spain. Spain ceded the Florida Territory to the U.S., the U.S. gave fringe areas in the West to Spain, and the boundary was established between the U.S. and New Spain. The new boundary was to be the Sabine River north from the Gulf of Mexico to the 32nd parallel north, then due north to the Red River, west along the Red River to the 100th meridian west, due north to the Arkansas River, west to its headwaters, north to the 42nd parallel north, and finally west along that parallel to the Pacific Ocean. Informally this was called the "Step Boundary," although its step-like shape was not apparent for several decades. This is because the source of the Arkansas, which was believed to be near the 42nd parallel, is actually hundreds of miles south of that latitude, a fact that was not known until John C. Frémont discovered it in the 1840s.

The Adams–Onís Treaty thus delineated the southern (Red River) and primary western (100th meridian west) borders of the future state of Oklahoma. It was also by this treaty that the land comprising the Oklahoma Panhandle was separated from the rest of the future state and ceded to the Spanish government.

The Indian Relocation

In the early history of the United States as a nation, a challenging issue was the management of frontier settlement in the traditional lands of the Native Americans. One approach to obtain land in or near the established states was to relocate tribes to unsettled territory further west. In 1820 (Treaty of Doak's Stand) and 1825 (Treaty of Washington City), the Choctaw were given lands in the Arkansas Territory (including in the current state of Oklahoma) in exchange for part of their homeland, primarily in the state of Mississippi.

This approach became more formalized in 1830 via the passage of the Indian Removal Act. This act gave President Andrew Jackson the power to negotiate treaties for removal with Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River. The treaty called for the Indians to give up their eastern land for land in the west. Those who wished to stay behind were required to assimilate and become citizens in their state. For the tribes that agreed to Jackson's terms, the removal was peaceful, however those who resisted were eventually forced to leave.[14]

Part of what became Oklahoma was designated as the home for the relocation of the "Five Civilized Tribes". Later the area would be referred to as Indian Country or Indian Territory. The goal was to provide ample lands for the relocation of Native Americans in the eastern states who did not wish to assimilate.

The Choctaw was the first of the "Five Civilized Tribes" to be removed from the southeastern United States. In September 1830, Choctaws in Mississippi agreed to terms of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and prepared to move west.[15][16] The phrase "Trail of Tears" originated from a description of the removal of the Choctaw Nation in 1831, although the term is usually used in reference to the Cherokee removal in 1838-39.[17]

The Creek refused to relocate and signed a treaty in March 1832 to open up a large portion of their land in exchange for protection of ownership of their remaining lands. The United States failed to protect the Creeks, and in 1837, they were militarily removed without ever signing a treaty.[14]

The Chickasaw saw the relocation as inevitable and signed a treaty in 1832 which included protection until their move. The Chickasaws were forced to move early as a result of white settlers and the War Department's refusal to protect the Indian's lands.[14]

In 1833, a small group of Seminoles signed a relocation treaty. However, the treaty was declared illegitimate by a majority of the tribe. The result was the Second (1835–42) and Third Seminole Wars (1855-58). Those that survived the wars eventually were paid to move west.[14]

The Treaty of New Echota of 1835 gave the Cherokees living in the state of Georgia two years to move west, or they would be forced to move. At the end of the two years only 2,000 Cherokees had migrated westward and 16,000 remained on their lands. The U.S. sent 7,000 soldiers to force the Cherokee to move without the time to gather their belongings. This march westward is known as the Trail of Tears, in which 4,000 Cherokee died.[14]

Republic of Texas and Kansas Territory

In 1821, New Spain gained its independence and became the short-lived Mexican Empire, followed by the Mexican Republic in 1824. Thus Mexico was the new owner of the lands to the south and west of the U.S. Territories. Texas, a province within Mexico, declared its independence from Mexico in 1836 following the Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas existed as a separate country from 1836 to 1845.

Texas was annexed as a state into the United States in 1845, and the Mexican-American War followed from 1846-1848. The war was concluded by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which the U.S. received the lands contentiously claimed from Mexico by Texas (including the Oklahoma Panhandle), as well as lands west of the Rio Grande to the Pacific Ocean (the Mexican Cession). Statehood for Texas was politically charged, as it added another "slave state" to the Union, and the conditions for its statehood were not resolved until the Compromise of 1850. One of the conditions was that to be admitted as a slave state, Texas had to set its northern border at parallel 36°30' north as per the Missouri Compromise. In addition to relinquishing claims on lands north of this parallel, Texas also had to give up its claim to parts of what is now New Mexico east of the Rio Grande, however in exchange the U.S. assumed Texas' $10 million debt.

On May 30, 1854, the Kansas and Nebraska Territories were established from the Indian Territory. The southern boundary of the Kansas Territory was set at the 37th parallel north, establishing the northern border of the future state of Oklahoma. This also resulted in an unassigned strip of land existing between Kansas's southern border and the northern border of the Texas Panhandle at 36°30' north, a neutral strip or "No Man's Land" that eventually became the Oklahoma Panhandle.

Civil War

In 1860, the Indian Territory had a population of 55,000 Indians, 8,400 black slaves owned by Indians, and 3000 whites. In 1861, as the American Civil War began, Texas forces moved north and the United States withdrew its military forces from the territory. Confederate Commissioner Albert Pike signed formal treaties of alliance with all the major tribes, and the territories sent a delegate to the Confederate Congress in Richmond. However, there were minority factions who opposed the Confederacy, with the result that a small-scale Civil War raged inside the territory. A force of Union troops and loyal Indians invaded Indian Territory and won a strategic victory at Honey Springs on July 17, 1863. By late summer 1863, Union forces controlled Fort Smith in neighboring Arkansas, and Confederate hopes for retaining control of the territory collapsed. Many pro-Confederate Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Indians fled south, becoming refugees among the Chickasaw and Choctaws. However, Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie, a Cherokee, captured Union supplies and kept the insurgency active. Watie was the last Confederate general to give up; he surrendered on June 23, 1865.[18]

During the Civil War, Congress passed a statute (still in effect) that gave the President the authority to suspend the appropriations of any tribe if the tribe is "in a state of actual hostility to the government of the United States … and, by proclamation, to declare all treaties with such tribe to be abrogated by such tribe." (25 USC Sec. 72)[19]

Post-Civil War Period

In 1866 the federal government forced the tribes that had allied with the Confederacy into new Reconstruction Treaties. Most of the land in central and western Indian Territory was ceded to the government. Some of the land was given to other tribes, but the central part, the so-called Unassigned Lands, remained with the government. Another concession allowed railroads to cross Indian lands. Furthermore, the practice of slavery was outlawed. Some nations were integrated racially with their slaves, but other nations were extremely hostile to the former slaves and wanted them exiled from their territory. It was also during this time that the policy of the federal government gradually shifted from Indian removal and relocation to one of assimilation.

In the 1870s, a movement began by whites and blacks wanting to settle the government lands in the Indian Territory under the Homestead Act of 1862. They referred to the Unassigned Lands as Oklahoma and to themselves as "Boomers". In 1884, in United States v. Payne, the United States District Court in Topeka, Kansas, ruled that settling on the lands ceded to the government by the Indians under the 1866 treaties was not a crime. The government at first resisted, but Congress soon enacted laws authorizing settlement.

In the 1880s, early settlers of the state's very sparsely populated Panhandle region tried to form the Cimarron Territory but lost a lawsuit against the federal government. This prompted a judge in Paris, Texas, to unintentionally create a moniker for the area. "That is land that can be owned by no man," the judge said, and after that the panhandle was referred to as No Man's Land until statehood arrived decades later.

Congress passed the Dawes Act, or General Allotment Act, in 1887 requiring the government to negotiate agreements with the tribes to divide Indian lands into individual holdings. Under the allotment system, tribal lands left over would be surveyed for settlement by non-Indians. Following settlement, many whites accused Republican officials of giving preferential treatment to ex-slaves in land disputes.

The Land Run of 1889

The United States entered into two new treaties with the Creeks and the Seminoles. Under these treaties, tribes would sell at least part of their land in Oklahoma to the U.S. to settle other Indian tribes and freemen.[20][21] This land would be widely called the Unassigned Lands or Oklahoma Country in the 1880s due to it remaining uninhabited for over a decade.[22]

In 1879, part-Cherokee Elias C. Boudinot argued that these Unassigned Lands be open for settlement because the title to these lands belonged to the United States and "whatever may have been the desire or intention of the United States Government in 1866 to locate Indians and negroes upon these lands, it is certain that no such desire or intention exists in 1879. The Negro since that date, has become a citizen of the United States, and Congress has recently enacted laws which practically forbid the removal of any more Indians into the Territory".[23]

On March 23, 1889, President Benjamin Harrison signed legislation which opened up the two million acres (8,000 km²) of the Unassigned Lands for settlement on April 22, 1889. It was to be the first of many land runs, but later land openings were conducted by means of a lottery because of widespread cheating—some of the settlers were called Sooners because they had already staked their land claims before the land was officially opened for settlement.

Oklahoma and Indian Territories

Indian Territory (lands owned by the Five Civilized Tribes and other Indian tribes from east of the Mississippi River) and Oklahoma Territory (lands set aside to relocate Plains Indians and other Midwestern tribes, as well as the recently settled "Unassigned Lands" and the Neutral Strip) were formally constituted by Congress on May 2, 1890 in the Oklahoma Organic Act. An Organic Act is a statute used by the U.S. Congress to create organized incorporated territories in anticipation of them being admitted to the Union as state(s). The following 16 years saw Congress pass several laws whose purpose was to join Oklahoma and Indian territories into a single State of Oklahoma.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oklahoma in the 1890s. |

Land Runs (1891-1895)

In 1893, the government purchased the rights to settle the Cherokee Outlet, or Cherokee Strip, from the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Outlet was part of the lands ceded to the government in the 1866 treaty, but the Cherokees retained access to the area and had leased it to several Chicago meat-packing plants for huge cattle ranches. The Cherokee Strip was opened to settlement by land run in 1893. Also in 1893 Congress set up the Dawes Commission to negotiate agreements with each of the Five Civilized Tribes for the allotment of tribal lands to individual Indians. Finally, the Curtis Act of 1898 abolished tribal jurisdiction over all of Indian Territory.

Angie Debo's landmark work, And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (1940), detailed how the allotment policy of the Dawes Commission and the Curtis Act of 1898 was systematically manipulated to deprive the Native Americans of their lands and resources.[24] In the words of historian Ellen Fitzpatrick, Debo's book "advanced a crushing analysis of the corruption, moral depravity, and criminal activity that underlay white administration and execution of the allotment policy."[25]

Oklahoma is best known to the rest of the world for its frontier history, famously represented in the 1943 Broadway hit musical Oklahoma! and its 1955 cinema version. The musical is based on Lynn Riggs' 1931 play, Green Grow the Lilacs. It is set in Oklahoma Territory outside the town of Claremore in 1906.[26]

Statehood

In 1902, the leaders of Indian Territory sought to become their own state, to be named Sequoyah. They held a convention in Eufaula, consisting of representatives from the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole tribes, known as the Five Civilized Tribes. They met again next year to establish a constitutional convention.

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention and statehood attempt

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention met in Muskogee, on August 21, 1905. General Pleasant Porter, Principal Chief of the Muscogee Creek Nation, was selected as president of the convention. The elected delegates decided that the executive officers of the Five Civilized Tribes would also be appointed as vice-presidents: William Charles Rogers, Principal Chief of the Cherokees; William H. Murray, appointed by Chickasaw Governor Douglas H. Johnston to represent the Chickasaws; Chief Green McCurtain of the Choctaws; Chief John Brown of the Seminoles; and Charles N. Haskell, selected to represent the Creeks (as General Porter had been elected President).

The convention drafted the constitution, established an organizational plan for a government, outlined proposed county designations in the new state, and elected delegates to go to the United States Congress to petition for statehood. If this had happened, the Sequoyah would have been the first state to have a Native American majority population.

The convention's proposals were overwhelmingly endorsed by the residents of Indian Territory in a referendum election in 1905. The U.S. government, however, reacted coolly to the idea of Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory becoming separate states; they preferred to have them share a singular state.

Murray's Proposal

Murray, known for his eccentricities and political astuteness, foresaw this possibility prior to the constitutional convention. When Johnston asked Murray to represent the Chickasaw Nation during Sequoyah's attempt at statehood, Murray predicted the plan would not succeed in Washington, D.C.. He suggested that if the attempt failed, the Indian Territory should work with the Oklahoma Territory to become one state. President Theodore Roosevelt and Congress turned down the Indian Territory proposal.

Seeing an opportunity for statehood, Murray and Haskell proposed another convention for the combined territories to be named Oklahoma. In 1906, the Oklahoma Enabling Act was passed by the U.S. Congress and approved by President Roosevelt. The act established several specific requirements for the proposed constitution.[27] Using the constitution from the Sequoyah convention as a basis (and the majority) of the new state constitution, Haskell and Murray returned to Washington with the proposal for statehood. On November 16, 1907 President Theodore Roosevelt signed the proclamation establishing Oklahoma as the nation's 46th state.

After statehood

The early years of statehood were marked with political activity. In 1910, the Democrats moved the capital to Oklahoma City, three years before the Oklahoma Organic Act allowed, in order to move away from the Republican hotbed of Guthrie. Socialism became a growing force among struggling farmers, and Oklahoma grew to have the largest Socialist population in the United States at the time, with the Socialist vote doubling in every election until the American entry into World War I in 1917.[28] However, the war drove food prices up, allowing the farmers to prosper, and the movement faded away. By the 1920s, the Republican Party, taking advantage of rifts within the Democratic Party, gained control in the state. The economy continued to improve,in the areas of cattle ranching, cotton, wheat, and especially, oil. Throughout the 1920s, new oil fields were continually discovered and Oklahoma produced over 1.8 billion barrels of petroleum, valued at over 3.5 million dollars for the decade.[29]

Oil

Although the first oil well in the United States was completed July 1850 in the old Cherokee Nation near Salina, it was in the early 20th century the oil business really began to get underway. Huge pools of underground oil were discovered in places like Glenpool near Tulsa. Many whites flooded into the state to make money. Many of the "old money" elite families of Oklahoma can date their rise to this time.

Throughout the 1920s, new oil fields were continually discovered and Oklahoma produced over 1.8 billion barrels of petroleum, valued at over 3.5 million dollars for the decade. In 1920 the spectacular Osage County oil field was opened, followed in 1926 by the Greater Seminole Oil Field. When the Great Depression Oklahoma and Texas oil was flooding the market and prices fell to pennies a gallon. In 1931 Governor William H. Murray, acting with characteristic decisiveness, used the National Guard to shut down all of Oklahoma's oil wells in an effort to stabilize prices. National policy became using the Texas Railroad Commission to set allotments in Texas, which raised prices as well for Oklahoma crude.[30]

Prosperous 1920s

The prosperity of the 1920s can be seen in the surviving architecture from the period, such as the Tulsa mansion which was converted into the Philbrook Museum of Art or the art deco architecture of downtown Tulsa.

Blacks

For Oklahoma, the early quarter of the 20th century was politically turbulent. Many different groups had flooded into the state; "black towns", or towns made of groups of African Americans choosing to live separately from whites, sprouted all over the state, while most of the state abided by the Jim Crow laws within each individual city, racially separating people with a bias against any non-White race. Greenwood, a neighborhood in Northern Tulsa, was known as Black Wall Street because of the vibrant business, cultural, and religious community there. The area was the site of the 1921 Tulsa Race War, one of the United States' deadliest race riots.

While many all-black towns sprang up in the early days of Oklahoma, many have disappeared. The table below lists 13 such towns that have survived to the present.

List of surviving all-Black towns in Oklahoma

| Town Name | County | 2010 Census

Population |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boley | Okfuskee | 1,184 | 39.6% black alone in 2010 |

| Brooksville | Pottawatomie | 63 | 20.0% black alone in 2010 |

| Clearview | Okfuskee | 48 | 75% black alone in 2010 |

| Grayson | Okmulgee | 59 | 53% African American alone in 2010 |

| Langston | Logan | 1,724 | 93.2% black alone in 2010 |

| Lima | Seminole | 53 | 34.0% African American alone in 2010 |

| Redbird | Wagoner | 137 | 67.9% black alone in 2010 |

| Rentiesville | McIntosh | 128 | 50.0% black alone in 2010 |

| Summit | Muskogee | 139 | 75.5% African American alone in 2010 |

| Taft | Muskogee | 250 | 82.0% African American alone in 2010 |

| Tatums | Carter | 151 | 79.5% black alone in 2010 |

| Tullahassee | Wagoner | 106 | 63.2% black alone in 2010 |

| Vernon | McIntosh | N. A. | Unincorporated community |

Socialists

The Oklahoma Socialist Party achieved a large degree of success in this era (the small party had its highest per-capita membership in Oklahoma at this time with 12,000 dues-paying members in 1914), including the publication of dozens of party newspapers and the election of several hundred local elected officials. Much of their success came from their willingness to reach out to Black and American Indian voters (they were the only party to continue to resist Jim Crow laws), and their willingness to alter traditional Marxist ideology when it made sense to do so (the biggest changes were the party's support of widespread small-scale land ownership, and their willingness to use religion positively to preach the "Socialist gospel"). The state party also delivered presidential candidate Eugene Debs some of his highest vote counts in the nation.

The party was later crushed into virtual non-existence during the "white terror" that followed the ultra-repressive environment following the Green Corn Rebellion and the World War I era paranoia against anyone who spoke against the war or capitalism.

The Industrial Workers of the World tried to gain headway during this period but achieved little success.

Impeachment of Governor Walton

Disgruntled Oklahoma farmers and laborers handed left-wing Democrat Jack C. Walton an easy election victory in 1922 as governor. One scandal followed another—Walton's questionable administrative practices included payroll padding, jailhouse pardons, removal of college administrators, and an enormous increase in the governor's salary. The conservative elements successfully petitioned for a special legislative recall session. To regain the initiative, Walton retaliated by attacking Oklahoma's Ku Klux Klan with a ban on parades, declaration of martial law, and employment of outsiders to 'keep the peace.' He declared martial law in the entire state and tried to call out the National Guard to block the legislature from holding the special session. That failed, and legislators charged Walton with corruption, impeached him, and removed him from office in 1923.[31]

Great Depression

The Great Depression lasted from 1929 to the late 1930s. Times were especially hard in 1930-33, as the prices of oil and farm products plunged, while debts remained high. Many banks and businesses went bankrupt. The Depression was made much worse for parts of the state by the Dust Bowl conditions. Farmers were hit the hardest and many relocated to the cities and established poor communities known as Hoovervilles. It also initiated a mass migration to California of "Okies" (to use the disparaging term common in California) in search of a better life, an image that would be popularized in American culture by John Steinbeck's novel, The Grapes of Wrath. The book, with photographs by Dorothea Lange, and songs of Woody Guthrie tales of woe from the era. The negative images of the "Okie" as a sort of rootless migrant laborer living in a near-animal state of scrounging for food greatly offended many Oklahomans. These works often mix the experiences of former sharecroppers of the western American South with those of the exodusters fleeing the fierce dust storms of the High Plains. Although they primarily feature the extremely destitute, the vast majority of the people, both staying in and fleeing from Oklahoma, suffered great poverty in the Depression years. Grapes of Wrath was a powerful but simplistic view of the complex conditions in rural Oklahoma, and fails to mention the great majority of people remained in Oklahoma.[32] The federal Agricultural Adjustment Act paid them to reduce production; prices rose and the distress was over,

Dust Bowl

Short-term drought and long-term poor agricultural practices led to the Dust Bowl, when massive dust storms blew away the soil from large tracts of arable land and deposited it on nearby farms or even far-distant locations. The resulting crop failures forced many small farmers to flee the state altogether. Although the most persistent dust storms primarily affected the Panhandle, much of the state experienced occasional dusters, intermittent severe drought, and occasional searing heat. Towns such as Alva, Altus, and Poteau each recorded temperatures of 120 °F (49 °C) during the epic summer of 1936.

World War II

The economy was clearly recovering by 1940, as farm and cattle prices rose. So did the price of oil. Massive Federal spending on infrastructure during the Depression was also beginning to show payoffs. Even before World War II broke out, the Oklahoma industrial economy saw increased demand for its products. The Federal government created such defense-related facilities as the Oklahoma Ordnance Works near Pryor, Oklahoma and the Douglas Aircraft plant adjacent to the Tulsa Municipal Airport. Numerous air bases dotted the map of Oklahoma. (See Oklahoma World War II Army Airfields).

Robert S. Kerr, governor 1943-46 was an oilman who supported the New Deal and used his network of connections in Washington to secure federal money. Oklahoma built and expanded numerous army and navy installations and air bases, which in turn brought thousands of well-paid jobs. Kerr went on to become a powerful Senator (1949–63) who watched out for the state's interests and especially for the oil and gas industry.[33]

Oklahoma consistently rated among the top 10 states in war-bond sales, as it used showmanship, the spirit of competition, house-to-house solicitations, and direct appeals to big business to mobilize patriotism, state pride, and the need to save some of the high wages that could not be spent because of rationing and shortages. The bond drives enlisted schoolchildren, housewives and retired men, giving everyone a sense of direct participation in the war effort.[34]

After World War II

The term "Okie" in recent years has taken on a new meaning in the past few decades, with many Oklahomans (both former and present) wearing the label as a badge of honor (as a symbol of the Okie survivor attitude). Others (mostly alive during the Dust Bowl era) still see the term negatively because they see the "Okie" migrants as quitters and transplants to the West Coast.

Major trends in Oklahoma history after the Depression era included the rise again of tribal sovereignty (including the issuance of tribal automobile license plates, and the opening of tribal smoke shops, casinos, grocery stores, and other commercial enterprises), the rapid growth of suburban Oklahoma City and Tulsa, the drop in population in Western Oklahoma, the oil boom of the 1980s and the oil bust of the 1990s.

In recent years, major efforts have been made by state and local leaders to revive Oklahoma's small towns and population centers, which had seen major decline following the oil bust. But Oklahoma City and Tulsa remain economically active in their effort to diversify as the state focuses more into medical research, health, finance, and manufacturing.

Aeronautical Economic Focus

Excluding governmental and education sectors, the largest single employers in the state tend to be in the aeronautical sector. The building of Tinker Air Force Base and the FAA's Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City, and American Airlines Engineering center, Maintenance Facility and Data Center in Tulsa provide the state with a comparative advantage in the Aeronautical sector of the economy. AAR Corporation has operations in both Oklahoma City and Tulsa, and The Boeing Company and Pratt & Whitney are building a regional presence next to Tinker AFB.

The state has a significant military (Air Force) presence with bases in Enid, Oklahoma (Vance Air Force Base) and Altus, Oklahoma (Altus Air Force Base), in addition to Tinker AFB in Oklahoma City. Additionally, Tinker houses the Navy's Strategic Communications Wing One.

For Aeronautical education and training, Tulsa hosts the Spartan College of Aeronautics and Technology that offers training in aviation and aircraft maintenance. Oklahoma University and Oklahoma State University both offer aviation programs. The FAA's Academy is responsible for training Air Traffic Controllers.

Oil and Gas Economic Focus

The oil and natural gas industry has historically been a dominant factor in the state's economy, second only to agriculture. The Tulsa Metropolitan Area has been home to more traditional oil companies such as ONEOK, Williams Companies, Helmerich & Payne, Magellan Midstream Partners with significant presence from ConocoPhillips. Oklahoma City is home to energy companies such as Devon Energy, Chesapeake Energy, OGE Energy, SandRidge Energy, Continental Resources. Duncan, Oklahoma is the birthplace of Halliburton Corporation. Significant research and education is done in the field by the Oklahoma University's Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy.

HVAC Manufacturing Economic Focus

The state has a surprisingly large concentration of companies that manufacture products that heat and cool buildings (HVAC). Among the companies in Tulsa are AAON (the former John Zink Company). In Oklahoma City are International Environmental, ClimateMaster, and Climate Control (subsidiaries of LSB Industries). Also, Governair and Temptrol (subsidiaries of CES Group) and York Unitary division of Johnson Controls have a major presence in the Oklahoma City metro. Also, Oklahoma State University has a major research effort in developing the Geothermal heat pump, and is headquarters for the International Ground Source Heat Pump Association.[35] Oklahoma State University–Okmulgee is known in the industry for its Air Conditioning Technology programs.

Oklahoma City Bombing

On April 19, 1995, in the Oklahoma City bombing, Gulf War veteran Timothy McVeigh bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people, including 19 children. Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were the convicted perpetrators of the attack, although many believe others were involved. Timothy McVeigh was later sentenced to death by lethal injection, while his partner, Terry Nichols, who was convicted of 161 counts of first degree murder received life in prison without the possibility of parole. It is said that McVeigh stayed at the El Siesta motel, a small town motel on US 64 in Vian, Oklahoma.

See also

- History of the South Central United States

- Aboriginal title in the United States

- Former Indian Reservations in Oklahoma

- Timeline of Oklahoma[36]

- City timelines

Further reading

- Baird, W. David, and Danney Goble. The Story of Oklahoma (2nd ed. 1994), 511 pages, high school textbook

- Baird, W. David, and Danney Goble. Oklahoma: A History (2008) 342 pp. ISBN 978-0-8061-3910-4, university textbook by leading scholars excerpts

- Castro, J. Justin, "Amazing Grace: The Influence of Christianity in Nineteenth-Century Oklahoma Ozark Music and Society," Chronicles of Oklahoma, (Winter 2008–2009), 86#4 pp 446–68.

- Dale, Edward Everett, and Morris L. Wardell. History of Oklahoma (1948), 574 pp; standard scholarly history [http://www.questia.com/library/book/history-of-oklahoma-by-edward-everett-dale-morris-l-wardell.jsp online edition from Questia

- Gibson, Arrell Morgan. Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (1981) excerpt and text search

- Goble, Danny. Progressive Oklahoma: The Making of a New Kind of State (1979)

- Goins, Charles Robert et al. Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (2006) excerpt and text search

- Gregory, James N. American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture (1991) excerpt and text search

- Hall, Ryan, "Struggle and Survival in Sallisaw: Revisiting John Steinbeck's Oklahoma," Agricultural History, (2012) 86#3 pp 33–56; actual responses of hard-hit farmers

- Lowitt, Richard, "Farm Crisis in Oklahoma, Part 1," Chronicles of Oklahoma, 89 (Fall 2011), 338–63.

- Reese, Linda Williams. Women of Oklahoma, 1890-1920, (1997) excerpt and text search

- Smith, Michael M., "Latinos in Oklahoma: A History of Four and a Half Centuries," Chronicles of Oklahoma, 87 (Summer 2009), 186–223.

- Wickett, Murray R. Contested Territory: Whites, Native Americans, and African Americans in Oklahoma 1865-1907 (2000) excerpt and text search

References

- ↑ W. David Baird; Danney Goble (2011). Oklahoma: A History: A History. University of Oklahoma Press. p. xii.

- ↑ "A Tapestry of Time and Terrain". USGS. 2003-04-17. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ↑ "Caddo Fundamentals: Mississippi World. Texas Beyond History. University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts.". Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- 1 2 "Tejas-Caddo Fundamentals-Caddo Timeline". Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ↑ Caddo Fundamentals, Idib

- ↑ Schlesier, Karl H. Plains Indians, 500-1500 AD: The Archaeological Past of Historic Groups. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994: 347–348.

- ↑ http://faculty-staff.ou.edu/D/Richard.R.Drass-1, accessed July 12, 2010/

- ↑ http://faculty-staff.ou.edu/D/Richard.R.Drass-1/Washita.html, accessed July 12, 2010

- ↑ Drass RR & TG Baugh (1997), The Wheeler Phase and cultural continuity in the Southern Plains. Plains Anthropologist 42: 183-204.

- ↑ "Plateaus and Canyonlands: Kiowa. Texas Beyond History. University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts.". Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ B.R. Kracht, Oklahoma Historical Society

- ↑ Cordell, Linda S. Ancient Pueblo Peoples. St. Remy Press and Smithsonian Institution, 1994. ISBN 0-89599-038-5. p. 151

- ↑ Stein, Mark (2008). How the States got their Shapes. HarperCollins. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-06-143138-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Indian removal". PBS. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- ↑ Baird, David (1973). "The Choctaws Meet the Americans, 1783 to 1843". The Choctaw People. United States: Indian Tribal Series. p. 36. Library of Congress 73-80708.

- ↑ Walter, Williams (1979). "Three Efforts at Development among the Choctaws of Mississippi". Southeastern Indians: Since the Removal Era. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ Len Green. "Choctaw Removal was really a "Trail of Tears"". Bishinik, mboucher, University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2008-06-04. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. eds. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War (2000) pp. 1031–34

- ↑ "Act of Congress, R.S. Sec. 2080 derived from act July 5, 1862, ch. 135, Sec. 1, 12 Stat. 528.". Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ↑ "Treaty with the Seminole, 1866". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Volume II, Treaties. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ "Treaty with the Creek, 1866". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Volume II, Treaties. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ "Unassigned Lands". Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2005-12-19. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ "Elias Boudinot 1879 Map of Indian Territory". Tulsa Genealogical Society. Archived from the original on 2005-12-13. Retrieved 2006-06-09.

- ↑ And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1940; new edition, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984), ISBN 0-691-04615-8.

- ↑ Ellen Fitzpatrick, History's Memory: Writing America's Past, 1880–1980 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-674-01605-X, p. 133, excerpt available online at Google Books.

- ↑ Broadway - The American Musical: Oklahoma. Educational Broadcasting Corporation. 2004. PBS. Retrieved: September 5, 2007

- ↑ Dianna Everett. "Enabling Act (1906)." Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Baird and Goble, The Story of Oklahoma, (1994) p. 346

- ↑ Baird and Goble, The Story of Oklahoma, (1994) p. 366

- ↑ Baird and Goble, The Story of Oklahoma, (1994) p. 366ff

- ↑ Brad L. Duren, "'Klanspiracy' or Despotism? The Rise and Fall of Governor Jack Walton, Featuring W. D. McBee," Chronicles of Oklahoma 2002-03 80(4): 468-485

- ↑ Ryan Hall, "Struggle and Survival in Sallisaw: Revisiting John Steinbeck's Oklahoma," Agricultural History (2012) 86#3 pp 33-56.

- ↑ Ann Hodges Morgan, Robert S. Kerr: The Senate Years (1980)

- ↑ Carol H. Welsh, "'Back The Attack': The Sale Of War Bonds In Oklahoma," Chronicles of Oklahoma (1983) 61#3 pp 226-245

- ↑ "What is IGSHPA?". Igshpa.okstate.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project (1941), "Chronology", Oklahoma: a Guide to the Sooner State, American Guide Series, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

External links

- Oklahoma Online Atlas

- The Official Web Site of Oklahoma|

- USDA Oklahoma State Facts

- Tourism Official Website

- Photos and books about Oklahoma, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - European Exploration

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory

- Oklahoma Oral History Research Program