History of Manchester Metrolink

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Metrolink |

|---|

|

The history of Metrolink begins with its conception as Greater Manchester's light rail system in 1982 by the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive, and spans its inauguration in 1992 and the successive phases of expansion.

Background

A light rail system for Greater Manchester was born of a desire by the Greater Manchester County Council to fulfil its obligations to provide "an integrated and efficient system of public transport" under its structure plan and the Transport Act 1968.[1] Greater Manchester's public transport network suffered from poor north – south connections, exacerbated by the location of Manchester's main railway stations, Piccadilly and Victoria,[2][3] which were unconnected and located at opposing edges of its city centre.[1][3] Piccadilly and Victoria were built in the 1840s by rival companies on cheaper land on the fringes of the city centre, resulting in poor integration and access to the central business zone.[4]

As early as 1839, in anticipation of the stations being built, a connecting underground railway tunnel was proposed but abandoned on economic grounds,[2][4] as was an overground suspended-monorail in 1966.[5] SELNEC Passenger Transport Executive — the body tasked with improving public transport for Manchester and its surrounding municipalities in the 1960s – made draft proposals for a Picc-Vic tunnel,[6] "a proposed rail route beneath the city centre" forming "the centrepiece of a new electrified railway network for the region".[7] Despite investigatory tunnelling under the Manchester Arndale shopping centre,[7] when the Greater Manchester County Council presented the project to the Government of the United Kingdom in 1974,[8] it was unable to secure the necessary funding,[9] and was abandoned on economic grounds when the County Council dropped the plans in 1977.[6][8]

Proposals

In 1982, the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (GMPTE; the successor to SELNEC PTE) concluded that an overground metropolitan light rail system to replace or complement the region's under-used heavy railways was the most economical solution to improving Greater Manchester's public transport network, which suffered from poor integration and outdated infrastructure;[3] a Rail Study Group, composed of officials from British Rail, Greater Manchester County Council and GMPTE formally endorsed the scheme in 1984.[1]

1984 proposals

Abstract proposals based on light rail systems in North America and continental Europe,[10] and a draft 62-mile (100 km) network consisting of three lines were presented by the Rail Study Group to the Government of the United Kingdom for funding in 1984.[6] The proposed system was described as a "Light Rapid Transit" (LRT) network, "a cross between a tram and a train". The network was planned to begin operation in 1989 pending approval from the Government, and construction costs were estimated at £42.5 million. [11]

The proposals outlined a network of three lines traversing Greater Manchester, linking converted heavy rail lines with an on-street tramway through Manchester city centre. A fleet of two-car vehicles (known as "supertrams") with a top speed of 80 km/h would run services at a ten-minute frequency.

The lines proposed were:[11]

| Line A: Altrincham – Hadfield/Glossop |

Line B: Bury – Rose Hill/Marple |

Line C: Rochdale – East Didsbury |

|---|---|---|

| connecting the Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway to the Glossop Line | connecting the Bury-Manchester line to part of the Hope Valley Line | connecting the Oldham Loop Line to the re-opened Manchester South District Line |

Obtaining Government grants towards development was not easy and subject to certain criteria,[12] and it was proposed to build the system in phases, beginning with the Altrincham and Bury lines, and the city centre track as far as Piccadilly.[11]

1987 proposals

In 1987, when powers and funding had been secured for Phase 1 of the network to go ahead, the brand name Metrolink was first introduced.[13]

Around this time, proposals were put forward by GMPTE for further extensions to the network; in addition to the Bury/Altrincham lines and city centre tracks already confirmed, it was envisaged that the network be extended with lines along the Manchester Ship Canal in Salford and Trafford. Station names vary from the 1984 proposals, for instance with the renaming of Central tram stop to G-Mex, and the addition of Cornbrook. A spur into Rochdale town centre was also proposed.[13]

| Altrincham – Hadfield/Glossop | Bury – Marple/Rose Hill | Rochdale Bus Station – East Didsbury | Broadway/Dumplington – Piccadilly Gardens |

|---|---|---|---|

| As the 1984 proposals | Bury Line/Hope Valley Line, as the 1984 proposals | Oldham Loop Line/Manchester South District Line – as the 1984 proposals, with an extension from Rochdale to Wet Rake and the bus station | a new line to Salford Quays |

Of these proposals, parts have survived as extension plans: the lines to Rochdale and East Didsbury formed part of the Phase 3; the Eccles Line is a modified version of the proposed extension into Salford Quays. The proposal to convert the Marple/Rose Hill and Hadfield/Glossop lines to Metrolink running was abandoned, and does not feature in the current Phase 3 expansion plans. The Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority did, however, commission in 2004 a feasibility study into converting the Marple line for tram-train operation; and in this revised form it remains on the "reserve list" of proposals for future Metrolink expansion, and was proposed to the Department for Transport in 2008 as a candidate for the national tram-train pilot.

Project Light Rail

British Rail Engineering Limited (BREL) began researching developments in light rail technology around the world, and in 1986 identified a light rail vehicle designed by the Urban Transportation Development Corporation in Canada for the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (UTDC) in California, USA, as an example of the type of LRV that could run in British cities. BREl planned to organise a live demonstration by shipping a UTDC vehicle which had been on display at the 1986 World Expo in Vancouver. Manchester was selected as the preferred venue for the demonstration as the city had the most developed light rail proposals, but negotiations to loan the vehicle fell through and the event was postponed until spring 1987.[14]

The event that eventually took place in Manchester, billed as Project Light Rail was jointly staged by GMPTE, British Rail, BREL, GEC Alsthom, Balfour Beatty and Fairclough Civil Engineering. It was the first major public relations event for GMPTE to promote the light rail proposals for Manchester and involved a public demonstration of an operational Docklands Light Railway train which was on loan from GEC Transportation Projects, DLR P86 number 11. The train had been shipped over to Britain from the manufacturer, Linke-Hofmann-Busch, in Salzgitter, Germany, prior to its introduction onto the Docklands system in London.

The event was formally opened by Minister of State for Transport David Mitchell, on 10 March 1987 and public demonstrations took place over two weekends (14/15 and 20/21/22) in March 1987 on a stretch of freight-only railway track, the Fallowfield Loop line. A number of locations had been considered, but the Fallowfield line was chosen because it still had track in place but was not a major passenger route. Originally the organisers had planned to use the disused Reddish depot but instead they decided to construct a temporary station on the site of the former Hyde Road railway station goods yard, adjacent to Debdale Park in the Gorton area of Manchester. The station, named Debdale Park, consisted of a single timber platform. The test track was closed to normal heavy rail traffic on demonstration days, and at night the DLR train was stationed in a siding and the line was re-opened to freight trains. An exhibition also exhibited examples of street track, overhead line and platform facilities.[15][16][17][15]

Tickets were sold for the event at 50p (25p for children) and a free shuttle bus was provided from Piccadilly station. Visitors were given a short ride on the DLR vehicle along a 1.6-kilometre (0.99 mi) stretch of track, from just north of the Hyde Road junction to just south of the closed Reddish depot. The DLR train was specially fitted with a pantograph and powered by overhead line, and was driven manually rather than in automatic mode, which was to be normal practice when in operation on the Docklands system. New 750 v DC overhead line equipment was also erected, using masts designed by Balfour Beatty for the Tuen Mun Light Rail in Hong Kong.[15]

After the public event, Debdale Park station was dismantled and the timber platform was used to build the new Hag Fold railway station near Wigan; and the electric overhead line equipment was taken down and re-used at the Heaton Park Tramway on the lakeside extension. The demonstration train DLR Number 11 was transported to London where it was put into operation on the Docklands Light Railway.[18][15]

A mock-up prototype version of a T-68 vehicle was put on public display while the Metrolink system was under construction in 1990.

Delivery

Phase 1, Bury, Altrincham and Manchester city centre

Conversion of the East Lancashire Railway (Bury-to-Victoria) and Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway (Altrincham-to-Piccadilly) heavy rail lines, and creation of a street-level tramway[19] through Manchester city centre to unite the lines as a single 19.2-mile (30.9 km) network,[20] was chosen for Phase 1 because the two heavy rail lines were primarily used for commuting to central Manchester, and would improve north – south links and access to the city centre.[21][22][23][20] The required parliamentary authority to proceed with Phase 1 was obtained with two Acts of Parliament – the Greater Manchester (Light Rapid Transit System) Act 1988 and Greater Manchester (Light Rapid Transit System) (No. 2) Act 1988.[24]

On 27 September 1989, following a two-stage tender exercise, the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority awarded a contract to the GMA Group (a consortium composed of AMEC, GM Buses, John Mowlem & Company, and a General Electric Company subsidiary)[25] who formed Greater Manchester Metro Limited to design, build, operate and maintain Phase 1 of Metrolink.[26] The contract was approved by Michael Portillo on behalf of the Department for Transport on 24 October 1989, and formally signed on 6 June 1990.[26]

The Bury line was closed in stages between 13 July 1991 and 17 August 1991, after which the 1200V DC third rail electrified line was adapted for a 750 V DC overhead line operation.[27] In Manchester city centre, a tramway – built with network expansion in mind[28] – from Victoria to Piccadilly via Market Street and Piccadilly Gardens connected Bury to Altrincham via Manchester; The overhead structures and wiring of the Altrincham line were adapted for light rail.[27] As well as upgrades to signalling and stations on the network, a combined headquarters, depot and control centre was built at Cheetham Hill on Queens Road, north of Victoria station,[27] at a cost of £8 million (£15,500,000 as of 2016[29]).[30]

Initially projected to open in September 1991, then promised for 21 February 1992,[31] Metrolink began operation on 6 April 1992 with a service between Victoria and Bury.[32][33] Along with the Tyne and Wear Metro and Docklands Light Railway, it helped to reintroduce light rail to the United Kingdom.[34][35] The network was expanded beyond Victoria to G-Mex tram stop on 27 April 1992; a service through to Altrincham joined the network on 15 June 1992,[33] completing Phase 1 and enabling use of all 26 T-68 vehicles acquired for the operation.[27][36] Queen Elizabeth II declared Metrolink open at a ceremony in Manchester on 17 July 1992, adding that Metrolink would improve communication between northern and southern Greater Manchester.[36][33][37] After the ceremony the Queen visited Manchester Town Hall and rode from St Peter's Square to Bury to visit Bury Town Hall.[36][33]

Then costing £145 million (£270,600,000 as of 2016[29])[38] Phase 1 was expected to carry 10 million passengers per year,[39] but surpassed this figure by the 1993/94 fiscal year, and every year thereafter.[40] In recognition of passenger demands and the decommissioning of the Arndale bus station after the 1996 Manchester bombing, adjustments were made to Phase 1 to the design of Manchester City Council's city centre masterplan, by modifying Market Street tram stop to handle two-way traffic, demolishing High Street tram stop in 1998 and creating a new stop for Shudehill Interchange in 2002.[41][42] Sections of track in the city centre were relaid following damage to the road surface adjacent to the line.[43] By 2003, Phase 1 was deemed a "long-term success" by GMPTE, and, with overcrowding at peak times, carried more than 15 million passengers per year.[44][45]

Phase 2, Salford Quays, Eccles

Extension of the Metrolink network was intended to be continuous with successive expansion phases delivered in strict order of priority.[46][47] GMPTE wanted to repeat its "success" with Phase 1 by converting other parts of Greater Manchester's under-utilised suburban rail network.[48] However, changes in circumstances and new opportunities, combined with a shift in government policy following the early 1990s recession stalled the immediate expansion of Metrolink after Phase 1.[47][49] Phase 1a, a proposed east – west route from Eastlands to Dumplington via Salford Quays was muted by uncertainty surrounding the Manchester bid for the 2000 Summer Olympics, the (unbuilt) Trafford Centre, and regeneration of Manchester Docks respectively.[46][50] Nevertheless, throughout the 1990s, the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority continued to acquire rights to construct Metrolink lines under the Transport and Works Act 1992.[38]

During the 1990s, Salford Quays became a business district specifically redeveloped for commerce, leisure, culture and tourism with a high density of business units and modern housing, complemented by a cinema complex, office blocks, and waterfront promenade.[51] As it had poor public transport integration and no rail provision, it was earmarked for a potential Metrolink line as early as 1986 and legal authority to construct the line through the Quays was acquired in 1990.[38][52] The Quays received millions of pounds of investment and a public consultation and public inquiry resulted in government endorsement in 1994. In autumn 1995 a 4-mile (6.4 km) Metrolink line branching from Cornbrook tram stop to Eccles via Salford Quays capitalising on the regenerated Quayside was confirmed as Phase 2 of Metrolink.[38][27][52] No funding came from central government and money was raised from the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority (GMPTA), the European Regional Development Fund and private developers.[38][52] In April 1997 Altram, a consortium of the Serco, Ansaldo and John Laing was appointed to construct the Eccles Line; Serco, responsible for the Sheffield Supertram would operate the whole network under contract; Ansaldo provided six additional vehicles — T-68As – and signalling equipment. Construction work officially began on 17 July 1997.[38][52][53]

The Eccles Line was officially opened as far as Broadway tram stop on 6 December 1999 by the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, who praised Metrolink as "exactly the type of scheme needed to solve the transport problems of the metropolitan areas of the country";[54][44] a service to Eccles Interchange joined the network on 21 July 2000,[27][38] and was officially declared open by Anne, Princess Royal at a ceremony on 9 January 2001.[55] On completion, Phases 1 and 2 gave Metrolink a total route length of 24 miles (39 km).[56] Phase 2 was predominantly privately funded and cost £160,000,000 (£242,870,000 as of 2016).[29][38] Salford City Council considered Phase 2 "an important contribution to Salford's public transport network, providing a fast and frequent service between Eccles, Salford Quays and Manchester city centre".[57] But, in competition with comparatively quicker and cheaper buses, the line navigated the Quays on a slow and meandering route, and failed to reach its initial passenger targets.[49] Patronage increased during the 2000s as the Eccles Line steadily increased in popularity in keeping with a rise in passenger numbers across the whole Metrolink system and was beginning to become overcrowded by the end of the decade.[57]

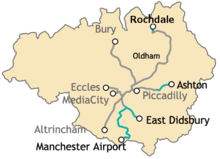

Phase 3

In 2000, officials and transport planners in Greater Manchester considered Metrolink to be a "phenomenal success".[38] The system was exceeding patronage targets and reducing traffic congestion on roads running parallel to its lines.[49] Consequently, when the Transport Act 2000 required passenger transport executives to produce local transport plans, GMPTE's top public transport priority was a third phase of Metrolink expansion, which would create four new lines along key transport corridors in Greater Manchester: the Oldham and Rochdale Line (routed northeast to Oldham and Rochdale), the East Manchester Line (routed east to East Manchester and Ashton-under-Lyne), the South Manchester Line (routed southeast to Chorlton-cum-Hardy and East Didsbury), and the Airport Line (routed south to Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport).[58] The East Manchester Line would capitalise on serving the City of Manchester Stadium, a host venue of the 2002 Commonwealth Games.[59][60] Satisfied it would deliver a key policy commitment with faster expansion and greater value from economies of scale,[38][44] GMPTE and the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (AGMA) lobbied central government to provide partial funding to upgrade the current network with a new depot, passenger information displays, and construct four new lines in a single Phase 3 contract (dubbed the "Big Bang") worth £489,000,000 (£742,300,000 as of 2016).[29][38][61][27][60][62][63]

Conceding that it would be "very difficult" to bring Metrolink to the City of Manchester Stadium by 2002, the Government accepted its importance to Greater Manchester and the Commonwealth Games on 22 March 2000, with an announcement from Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott that a £289,000,000 government contribution to fund Phase 3 would make Metrolink "the envy of Europe".[61][60][64] The remaining £200,000,000 was assembled from the private sector by July 2000.[38][60] Following the announcement, preparatory work such as legal costs, land acquisition and construction of rail bridges over the River Medlock was actioned.[63][64] However, Metrolink made a loss in 2002 and failed to reduce traffic congestion in Manchester city centre.[65] Costs for Phase 3 implementation were revised in the December after the 2002 Commonwealth Games, totalling £820,000,000 (£1,203,000,000 as of 2016),[29] meaning Metrolink required a Government contribution of at least £520,000,000.[54] With costs predicted to rise further, and concerns raised over light rail procurement nationally,[66] on 20 July 2004, Alistair Darling (the Secretary of State for Transport) announced the Government had withdrawn its share of funding Metrolink due to excessive costs.[54][63][67]

In response, highlighting the legal costs and demolition of homes, schools and offices in anticipation of the new lines,[63][64] the Get Our Metrolink Back on Track (or Back on Track )[62] campaign spearheaded by the Manchester Evening News and Members of Parliament from Greater Manchester was organised to lobby the Department for Transport to fund Phase 3.[68][66][63][69] On 16 December 2004 Alistair Darling announced that the government would fund Phase 3 – but not at any price, capping its investment for Metrolink enhancements at £520,000,000.[66][63] An initial £102,000,000 funding package was granted by the Government in July 2005 for Phase 3 preparatory work, and a Carillion-led track renewal programme for 12 miles (19 km) of Phase 1 line – still using original British Rail track – that was causing damage to vehicles and discomfort for passengers.[45] Following negotiations between central government and GMPTE and AGMA, Phase 3 funding was confirmed by Douglas Alexander on 6 July 2006,[63] albeit with adjustments (such as axing the Wythenshawe Loop)[70] and splitting the project into two stages: Phase 3a, elements of expansion funded by government investment; and Phase 3b, elements requiring an alternative funding source.[62][66] The MPact-Thales consortium, composed of Laing O'Rourke, VolkerRail and the Thales Group, was appointed to design, build and maintain the 20 miles (32 km) of new line plus a new depot at Old Trafford.[27][66] A 0.25-mile (0.40 km) spur off the Eccles Line to the new MediaCityUK development at Salford Quays, funded separately by the Northwest Regional Development Agency (NWRDA), would also fall to Mpact-Thales.[27][66][53]

Phase 3a, Oldham, Rochdale, East Manchester Line

Phase 3a, dubbed the "Mini Bang",[62] or "Little Bang",[71] was an extension scheme approved by the government on 6 July 2006, with final sign off and release of Treasury funds in May 2008.[53] In addition to the separately NWRDA-funded spur from the Eccles Line to MediaCityUK, Phase 3a involved converting the 14-mile (23 km) Oldham Loop heavy rail line from Victoria to Rochdale via Oldham, building a new 1.7-mile (2.7 km) South Manchester Line from Trafford Bar to St Werburgh's Road in Chorlton-cum-Hardy (on a closed section of Cheshire Lines Committee railway), and construction of a new 4-mile (6.4 km) East Manchester Line from Piccadilly to Droylsden.[53][45][62][72] The Oldham and Rochdale and South Manchester Lines were funded by a £244,000,000 lump sum from the government.[53][62] The East Manchester Line to Droylsden was funded by borrowings by GMPTE that would be repaid over 30 years using fare revenue from Metrolink.[45]

The Oldham Loop Line, subsidised by GMPTE and used for suburban commuting, closed on 3 October 2009 allowing work to convert the line from heavy rail to Metrolink,[73][74] although preparatory work on Central Park tram stop and a flyover at Newton Heath over the heavy Caldervale Line commenced in 2005.[75] Conversion of the Oldham Loop for Metrolink allowed for the addition of new stops along the line, including Monsall, South Chadderton, and Newbold;[76] Kingsway Business Park tram stop was authorised at a late stage of planning in July 2011 once the Phase 3b-Drake Street tram stop was abandoned (on technical and economic grounds) and additional funding was procured from Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council and Kingsway Business Park's private developer Wilson Bowden.[77]

The planned opening of Phase 3a services was initially delayed on each line by months due to faults with a new £22,000,000 digital signalling and control system known as the Tram Management System, or TMS, designed by the Thales Group.[78] Services on the spur from the Eccles Line to MediaCityUK tram stop were expected to commence during Summer 2010,[53] and began on 20 September 2010,[79] serving MediaCityUK, a 200-acre (81 ha) development for creative and digital mass media organisations,[66][53] and The Lowry, a combined theatre-gallery and Greater Manchester's most visited tourist attraction.[38][80] On its inauguration, TMS experienced several faults on the expanded Eccles Line, causing "chaos" at MediaCityUK, and 24 service delays on the network between September 2010 and February 2011.[78][81] On the South Manchester Line, services to St Werburgh's Road tram stop were expected to commence in spring 2011,[53] but delayed until 7 July 2011, due to problems with TMS.[71][72] On the Oldham and Rochdale Line, services from Manchester to Central Park and Oldham Mumps were expected to open in spring 2011 and autumn 2011 respectively,[53][82] but problems with TMS and the need to renew structures delayed services until 13 June 2012, when 7.1 miles (11.4 km) of the line from Victoria to Oldham Mumps tram stop opened in a single stage.[76][83][84]

After three months in operation, Metrolink services to Oldham were hailed a "huge success" by TfGM, with 250,000 passengers on the line between June and September,[69] strengthening TfGM's position that Phase 3a would raise daily ridership on Metrolink to 90,000.[53] Originally planned to open in spring 2012,[82] then delayed to autumn 2012,[85] a service on the Oldham and Rochdale Line from Oldham Mumps as far as Shaw and Crompton tram stop began on 16 December 2012.[86][87] In January 2013, a contract dispute between TfGM and Thales Group over missed deadlines and poor performance of TMS resulted in TfGM withholding payments for unfulfilled construction targets.[78] Services to Rochdale and Droylsden were scheduled for a spring 2012 opening date,[53][88] but delayed by months because of problems with the implementation of TMS, prompting outrage from Members of Parliament representing these areas.[89][90] The East Manchester Line to Droylsden opened to selected residents of Manchester and Tameside on 8 February 2013, and to the general public on 11 February 2013.[89][91] On 28 February 2013, passenger services expanded along the 4.6-mile (7.4 km) stretch of the Oldham and Rochdale Line between Shaw and Crompton and Rochdale railway station, completing Phase 3a, and giving Metrolink a total network length of 43 miles (69 km).[92][93] On 9 May 2013, TMS was successfully implemented in the City Zone, providing real-time passenger information displays at all stops in Manchester city centre.[94]

Phase 3b: Ashton-under-Lyne, East Didsbury and Manchester Airport

Phase 3b was revealed in July 2006 when Phase 3 was split into two smaller phases.[95] A range of motivators pushed transport planners to pursue Phase 3b, including attracting new passengers, value to the economy, reduction of road traffic congestion, regeneration, and improved access to town centres, business districts and labour markets.[96] Under Phase 3b plans, Metrolink proposed to extend the East Manchester Line by 2.4 miles (3.9 km) from Droylsden to Ashton-under-Lyne;[97] extend the South Manchester Line by 2.7 miles (4.3 km) from St Werburgh's Road to Didsbury;[98] and create a new 9-mile (14 km) Airport Line to Manchester Airport from a junction at St Werburgh's Road.[99] Phase 3b enacted plans first drawn up in 1983, laid before Parliament in 1988, and approved by the government in 1991 to re-route and extend the Oldham and Rochdale Line at a cost of £124,500,000 with a street running route through Oldham and Rochdale town centres, both of which were poorly served by using the outlying Oldham Mumps and Rochdale railway stations alone.[95][100][76][101][102]

Tasked with procuring funds for Phase 3b from sources other than central Government, in July 2007 GMPTE and AGMA submitted a bid to the Transport Innovation Fund, which would release a multimillion-pound sum for public transport improvements linked to viable anti-road traffic congestion strategies.[103][104] A referendum on the Greater Manchester Transport Innovation Fund was held in Greater Manchester on 19 December 2008,[105] in which 79% of voters rejected plans for public transport improvements linked to a peak-time weekday-only Greater Manchester congestion charge.[106] In May 2009, Greater Manchester Integrated Transport Authority (formerly GMPTA) and AGMA agreed to create the Greater Manchester Transport Fund, £1.5billion raised from a combination of a levy on council tax in Greater Manchester, government grants, contributions from the Manchester Airports Group, Metrolink fares and third-party funding for "major transport schemes" in the region.[107][101] Phase 3b was approved with funding on a line-by-line basis between March and August 2010.[97][101]

Construction work for all Phase 3b lines began in March 2011.[108] On the Airport Line, a 580-tonne steel bridge was erected in Wythenshawe over the M56 motorway on 25 November 2012.[109] Following the closure of Mosley Street tram stop on 17 May 2013,[110] the 2.7-mile (4.3 km) route of the South Manchester Line from St Werburgh's Road to East Didsbury tram stop was the first section of Phase 3b line to open on 23 May 2013 – three months ahead of schedule.[98][111] The East Manchester Line was completed on 9 October 2013 with a new service routed 2.1 miles (3.4 km) between Droylsden and Ashton-under-Lyne tram stop, taking the total system length to 47.7 miles (76.8 km).[112][113][114] The Oldham and Rochdale Line was completed with a street-running service through Oldham Town Centre on 27 January 2014,[115] and the addition of a street-running service between Rochdale railway station and Rochdale Town Centre on 31 March 2014, taking the total system length to 48.5 miles (78.1 km).[116]

On 3 November 2014, the network once again expanded, with a 14.5-mile (23.3 km) extension to Manchester Airport railway station, bringing the length of the system to 92.5 kilometres (57.5 mi), making it the longest tramway in the United Kingdom, and the longest light railway.[117] It opened more than one year early,[118] and at a cost of £368 million.[119]

Branding and publicity

When proposals to build a light rail system for Greater Manchester were revealed in 1984, the system was originally described as "Light Rapid Transit", or LRT for short. Artists' impressions of the proposed LRT vehicles depicted them in orange and white livery, bearing the Greater Manchester Transport "M" logo, sharing the same branding as GMT buses of the period.[11]

The Metrolink name was first introduced in 1987 in time for the tendering process to build and operate the system. Promotional literature distributed at this time contained new illustrations of the light rail vehicles, depicted with light grey livery, an orange logo which used the Greater Manchester Transport "M" monogram to form the "M" of Metrolink and double orange stripes continuing along the sides of the vehicles.[13]

When the system opened in 1992, an aquamarine and grey colour scheme was used for vehicle livery, signage and publicity, and a new Metrolink logo was introduced which was composed of a stylised "M" monogram placed at an angle within a circle. Vehicles were originally painted white with a dark grey skirt and a turquoise stripe at base of body; around the opening of Metrolink's Phase 2 the livery was adapted to include aquamarine doors.[120]

In 2003, GMPTE introduced new branding for Metrolink to promote its proposals for the "Big Bang" network expansion project. The logo featured a new "M" symbol formed from yellow and blue upward arrows, with the strapline "Transforming our Future". This logo was not used on trams or signage, however.[121]

In October 2008 a new corporate identity was created by Hemisphere Design & Marketing Consultants of Manchester.[122] The design features a pale yellow and grey colour scheme, a logotype in the specially-commissioned Pantograph sans regular typeface by the Dalton Maag type foundry,[123] and the "M" symbol has been replaced by a diamond motif formed from a pattern of repeating circles. The designs have been applied to signage and publicity, and tram livery features yellow at the vehicle ends with grey sides and black doors. The yellow colour scheme has been likened to the Merseyrail branding used in neighbouring Liverpool.[124][125][126]

Operator

Metrolink was originally built and operated from 1989 by the consortium Greater Manchester Metro Limited (GMML). In 1997 the contract was awarded to a new consortium, Altram (Manchester) Limited, a consortium of Ansaldo Transporti, Serco, Laing and 3i.[127] Serco Metrolink, took over the operations and maintenance of the system on 26 May 1997. In March 2003, Serco Investments bought out its partners and Altram (Manchester) Limited became a wholly owned subsidiary of Serco.[128]

On 15 July 2007, Stagecoach commenced operating a 10-year contract to operate Metrolink.[129][130][131] Unlike Serco, Stagecoach did not own the concession, merely operated it on a fixed-term management contract. RATP Group bought the contract from Stagecoach on 1 August 2011.[132][133]

In October 2015, TfGM announced RATP Group, Keolis/Amey, National Express and Transdev had been shortlisted to bid for the next contract starting in July 2017.[134]

Modifications since construction

The following modifications to the system have taken place since the opening of Phase I in 1992.

- The original Market Street tram stop stop handled trams to Bury, with High Street tram stop handling trams from Bury. When Market Street was pedestrianised, High Street stop was closed, and Market Street stop was rebuilt to handle trams in both directions, opening in its new form in 1998.[135]

- Shudehill Interchange opened between Victoria station and Market Street in April 2003. The bus station complementing it opened on 29 January 2006.[135]

- Cornbrook tram stop was opened in 1999 on the Altrincham line to provide an interchange with the new line to Eccles. There was initially no public access from the street, but this changed on 3 September 2005 when the original fire exit was opened as a public access route.

- Two of the original stops; Mosley Street, and Woodlands Road were closed in 2013. The latter being replaced by two new stops (Abraham Moss and Queens Road) opened nearby.[136]

By the mid-2000s, most of the track on the Bury and Altrincham routes were 1960 track which needed to be relaid. In 2006 it was decided a £107 million programme to replace this worn track would take place in 2007.[137]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Holt 1992, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Williams 2003, p. 273.

- 1 2 Holt 1992, p. 4.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 22.

- 1 2 "Manchester unearths forgotten 1970s tube line". The Architects' Journal. London: architectsjournal.co.uk. 13 March 2012.

- 1 2 Holt 1992, p. 5.

- ↑ Donald, Cross & Bristow 1983, p. 45.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 4 Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (1984), Light Rapid Transit in Greater Manchester, GMPTE – publicity brochure

- ↑ Docherty, Iain; Shaw, Jon (2003). A New Deal for Transport?: The UK's Struggle with the Sustainable Transport Agenda. Blackwell Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4051-0631-3.

- 1 2 3 Metrolink Community Liaison (1987). "Metrolink – Light Rail in Greater Manchester". publicity brochure. Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority and Executive.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 36-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 37.

- ↑ "Debdale Park". Subterranea Britannica. Disused Stations. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Holt 1992, p. 24-5.

- ↑ Pearce, Alan; Hardy, Brian; Stannard, Colin (2000). Docklands Light Railway Official Handbook. Capital Transport Publishing. ISBN 1-85414-223-2.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 74.

- 1 2 Ogden & Senior 1991, p. 17.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 73.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 56.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1991, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 51.

- 1 2 Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kessell, Clive (30 November 2011). "Manchester Metrolink 20 Years of Evolution". The Rail Engineer. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Holt 1992, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 5 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1991, p. 53.

- ↑ Holt 1992, p. 87.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 4 Holt 1992, p. 90.

- ↑ "The History of Tramways and Evolution of Light Rail". Light Rail Transit Association.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 GMPTE 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ "Manchester's oldest Metrolink trams to be replaced". BBC News. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 GMPTE 2000.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 13.

- ↑ "Light rail and tram statistics: 2011/12". Department for Transport. 19 July 2012. Light rail and tram statistics 2011/12 and XLS tables (Table LRT0101). Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 290.

- ↑ Hall, J.R. (November 1995). "Design, build, operate and maintain contract as applied to Manchester's Metrolink". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Transport. Thomas Telford. 111 (4): 310–313. doi:10.1680/itran.1995.28033. ISSN 0965-092X.

- 1 2 3 GMPTE 2003, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 Kingsley, Nick (19 October 2007). "Manchester plays catch-up with Metrolink expansion". Railway Gazette International. London. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- 1 2 Ogden & Senior 1991, p. 63.

- 1 2 Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 91.

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 275.

- 1 2 3 Docherty & Shaw 2011.

- ↑ Ogden & Senior 1992, p. 148.

- ↑ "Salford Quays Milestones: The Story of Salford Quays" (PDF). Salford City Council. 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 GMPTE 2003, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Manchester Metrolink, United Kingdom". railway-technology.com. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Ward, David (2 August 2004). "Tram fury rattles ministers". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ "Whistle-stop Princess takes home hat souvenir". Manchester Evening News. 9 January 2001. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ "More money for UK light rail". Railway Gazette International. London. 1 January 2003. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Salford Infrastructure Delivery Plan" (PDF). Salford City Council. February 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester Local Transport Plan 2" (PDF). Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority. March 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ GMPTE (2000). "Metrolink is coming ..." (PDF) (Press release). Manchester: GMPTE Promotions. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "£289m for Metrolink 'Big Bang'". Manchester Evening News. 22 March 2000. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- 1 2 "£500m tram extension unveiled". BBC News. 22 March 2000. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Metrolink: back on track?". BBC News. 13 May 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Metrolink extension is announced". BBC News. 6 July 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Satchell, Clarissa (17 November 2005). "Bring on the Metro, urges bridge boss". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Trams fail to cut jams". Manchester Evening News. 23 April 2004. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 TfGM & GMCA 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ "Government scraps trams extension". BBC News. 20 July 2004. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Satchell, Clarissa (6 September 2004). "Moving plea to save Metrolink". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Oldham Metrolink line a huge success with 250,000 passengers in first three months". Manchester Evening News. 15 September 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ "Metrolink 'to axe hospital route'". BBC News. 22 June 2005. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 "On track at last: Commuters travel on new Metrolink tram service to south Manchester for first time". Manchester Evening News. 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 "First line opens under £1·4bn Manchester tram expansion". Railway Gazette International. London. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (1 October 2009). "Signalman reaches end of line". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ↑ "End of era as loop line is replaced". Manchester Evening News. 26 September 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ↑ Satchell, Clarissa (6 April 2005). "Tram interchange gets £36m go-ahead". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Metrolink trams reach Oldham Mumps". Railway Gazette International. London. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Jones, Chris (27 July 2011). "Kingsway developers to foot the bill for Metrolink tram stop". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Kirby, Dean (3 January 2013). "Metrolink tram bosses and signalling firm in court battle that could cost Greater Manchester taxpayers £42m". Manchester Evening News.

- ↑ "Metrolink trams pull in to MediaCityUK station for first time". Manchester Evening News. 20 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Brooks-Pollock, Tom (30 November 2011). "Lowry gallery and theatre is most popular tourist attraction in Greater Manchester". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (27 June 2011). "Rush-hour chaos for tram commuters after Metrolink computer breakdown". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- 1 2 GMPTE 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ "New tram operating system delays Metrolink extension". BBC News. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (8 June 2012). "Metrolink Oldham line set to open next Wednesday". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ Rudkin, Andrew; Korn, Helen (8 October 2012). "Metrolink opening date remains vague". Oldham Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (12 December 2012). "Shaw and Crompton Metrolink trams start this Sunday". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ "Metrolink stations 'to boost two Greater Manchester areas'". BBC News. 16 December 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ↑ GMPTE 2010, pp. 4–7.

- 1 2 Kirby, Dean (4 December 2012). "Opening of Metrolink tram service to Droylsden delayed until February 2013". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (4 January 2013). "MPs slam delays to new Metrolink lines to Rochdale and Droylsden". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "It's the final countdown" (Press release). Transport for Greater Manchester. 1 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ↑ "Next stop: Rochdale!" (Press release). Transport for Greater Manchester. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Next stop: Rochdale!". Rochdale Online. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Real-time tram information for city centre passengers". Transport for Greater Manchester. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- 1 2 Young 2008, p. 163.

- ↑ TfGM & GMCA 2011, p. 45.

- 1 2 "Ashton and Didsbury Metrolink extensions funded". Railway Gazette International. London. 8 March 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- 1 2 Kirby, Dean (14 May 2013). "Metrolink extension to East Didsbury to open next week- three months early". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ↑ "Manchester Metrolink starts Phase 3b". Railway Gazette International. London. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Holt 1992, pp. 92–93.

- 1 2 3 "Manchester Metrolink Phase 3b confirmed". Railway Gazette International. London. 5 August 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bringing Metrolink to Oldham and Rochdale" (PDF). Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority. 2000. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Young 2008, p. 160.

- ↑ "The Link" (PDF). Transport for Greater Manchester. 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ "Date set for C-charge referendum". BBC News. 29 September 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ Sturcke, James (12 December 2008). "Manchester says no to congestion charging". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- ↑ TfGM 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ "Manchester Metrolink starts Phase 3b". Railway Gazette International. London. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Britton, Paul (25 November 2012). "Giant construction project to position 580-tonne bridge over M56 completed eight hours early". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (12 May 2013). "Manchester city centre tram stop reaches the end of the line". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ Kirby, Dean (22 May 2013). "Destination Didsbury – Metrolink trams to start tomorrow, three months early". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ "New Metrolink service to Ashton opens" (Press release). Transport for Greater Manchester. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Kent-Smith, Emily (9 October 2013). "Metrolink tram service launches from Ashton-under-Lyne... and it's on time". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Britton, Paul (28 September 2013). "Metrolink service to Ashton-under-Lyne to start on October 9". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Flanagan, Emma (27 January 2014). "Landmarks on the new Oldham Metrolink line, and a driver's eye view tour of the route". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ Scheerhout, John (31 March 2014). "Passenger trams start running to and from Rochdale town centre for first time in 80 years". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Metrolink – The Airport Line has landed".

- ↑ "BBC News – Metrolink line to Manchester Airport opens a year early". BBC News.

- ↑ Charlotte Cox (20 June 2014). "Video: Manchester airport Metrolink line to open this year – Manchester Evening News". men.

- ↑ ":The Trams: Metrolink Liveries". The Trams. 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "Metrolink: Transforming our Future". GMPTE. 2003. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Work: a taster". Hemisphere Design and Marketing Consultants. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ↑ "Linking It All Up". Infoletter. Dalton Maag. March 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ Rail Magazine issue 603

- ↑ "Tram design on the right track". Manchester Evening News. 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ "New look for new trams". GMPTE. 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Altram takes Manchester Metrolink" Rail Privatisation News issue 42 14 November 1996 page 1

- ↑ "Past, Present and Future" (PDF). Metrolink. 2003. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Stagecoach signs Manchester Metrolink contract". Press release. Stagecoach Group. 2007-05-29. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Stagecoach take over tram service". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 15 July 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ "Stagecoach takes on trams" Rail Magazine issue 571 1 August 2007 page 15

- ↑ "RATP buys Manchester Metrolink operator". Railway Gazette International. 2 August 2011.

- ↑ "New owner for Metrolink" Rail Express issue 184 September 2011

- ↑ Manchester Metrolink operations shortlist announced Railway Gazette International 17 October 2015

- 1 2 "Metrolink in the City Centre". Light Rail Transit Association. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "New Queens Road Metrolink stop to open". Transport for Greater Manchester.

- ↑ "Metrolink tracks to be replaced". BBC News. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

Bibliography

- Docherty, Iain; Shaw, Jon (20 July 2011). A New Deal for Transport: The UK's struggle with the sustainable transport agenda. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5551-2.

- Donald, T.; Cross, M.; Bristow, Roger (1983). English Structure Planning. Routledge. ISBN 0-85086-094-6.

- GMPTE (2000). Metrolink, Transforming Our Future: A Network for the 21st Century. Manchester: GMPTE Promotions.

- GMPTE (2003). Metrolink: A Network for the 21st Century (PDF). Manchester: GMPTE Promotions.

- GMPTE (2009). The Link/2: Metrolink news and developments from GMPTE (PDF). Manchester: GMPTE Promotions.

- GMPTE (2010). The Link/3: Metrolink news and developments from GMPTE (PDF). Manchester: GMPTE Promotions.

- Holt, David (1992). Manchester Metrolink. UK light rail systems; no. 1. Sheffield: Platform 5. ISBN 1-872524-36-2.

- Ogden, Eric; Senior, John (1992). Metrolink. Glossop, Derbyshire: Transport Publishing Company. ISBN 0-86317-155-9.

- Ogden, Eric; Senior, John (1991). Metrolink: Official Handbook. Glossop, Derbyshire: Transport Publishing Company. ISBN 0-86317-164-8.

- TfGM (2012). Annual Report 2011/2012: Connecting Greater Manchester (PDF). Manchester: Transport for Greater Manchester.

- TfGM; GMCA (2011). Greater Manchester's third Local Transport Plan 2011/12 – 2015/16 (PDF). Transport for Greater Manchester.

- Williams, Gwyndaf (2003). The Enterprising City Centre: Manchester's Development Challenge. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25262-1.

- Young, Tony (2008). Tramways in Rochdale: Steam, Electric and Metrolink. Light Rail Transit Association. ISBN 978-0-948106-34-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manchester Metrolink. |

- www.lrta.org/manchester, a historical account of Metrolink from the Light Rail Transit Association

- www.metrolink.co.uk, the official Metrolink website

- www.metrolinkpromotions.co.uk, for official marketing, promotion and events

- www.tfgm.com, the official website of Transport for Greater Manchester