High-commitment management

High-commitment management emphasizes personal responsibility, independence, and empowerment of employees across all levels instead of focusing on one higher power it always intended to keep commitment at high level “calling all the shots”.[1]

A high commitment system is unusual in its job design and cultural structure. These practices emphasize getting the tasks complete, but do it in a way that their employees enjoy doing it. According to Harvard Business School Professor Michael Beer, “leaders develop an organizational design, business processes, goals and measures, and capabilities that are aligned with a focused, winning strategy.”[2] This kind of environment allows employees to approach tasks at ease, wearing jeans instead of suits and staying home to watch their children get on the bus for school before coming to work. Technology also plays a role in this system. Recently, technology has slaughtered barriers of communication, which makes this high commitment model fit that much better. That dad waiting for the bus can still answer phone calls and check emails for work, so is he working or is he spending time with his daughter? He can be doing both.[1] As long as the job gets done, this system is casual on how it gets done, relieving employees of constant stress.

A flat organizational structure is one of the biggest success factors. Individuals are responsible for their own decision-making and these decisions, their skill, and their performance is how they get paid. Instead of putting too much weight on the individual, “people are likely to see the locus of the control coming from ‘within’ through the adoption of self-created demands and pressures as opposed to external and making them feel subordinate.” [3] While these companies allow each employee to be a manager in their own way and try not to distinguish its structure by higher levels of employment, it doesn’t mean that they lack these higher powers entirely. It’s the fact that under this system people aren’t relying on the general managers, CEOs, or even other employees to do their work for them. This personal discipline is what drives the employees to help the company be successful.[4] and eliminates the chance at a thought like, “Why would I want to help my company become better if I know I’m just going to get yelled at?” [5]

Another focus of high commitment practices is their employee relationships. They only hire people who are flexible, determined, and are willing to handle challenges. Because this system relies on individual performance, there is a big emphasis on hiring the right people for the job. The detailed recruitment process can consist of many interviews with different members of the company, an induction course, and in some cases, team-building exercises.[3] Once found, the right employees help create a strong bond and high trust throughout the entire company.

High commitment workplaces are successful through their importance on an individual’s responsibility in order to help the team prosper. By creating a culture that motivates individuals to want to succeed while sustaining high commitment, “these firms stand out by having achieved long periods of excellence.” [6]

History

High-commitment management firms are designed by their founders or transformational chief executives to achieve sustained high commitment from employees. The application of high-commitment management in firms today originated from an alignment of the employees’ and the firm’s mission.[7] Sociologists attribute this congruence as a product of performance and psychological collaboration between the firm and its employees. Since its initial developments, high commitment management has been driven by self-regulated behavior and performance-driven group dynamics.[8] Contrary to the top-down leadership practices, high-commitment management took form as leaders engaged and listened to people, allowing ideas from different levels of the organization to push the firm forward.

Self-directed work teams

In a study of illumination in the workplace of Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company, a sociologist from Harvard Business School, Elton Mayo, concluded that when the organization established experimental work groups, “the individuals became a team and the team gave itself wholeheartedly and spontaneously to cooperation.”[9] Through a natural system of collaboration, the teams are not only responsible for the work but also the management of their group. Mayo’s research uncovered that teams under their own direction established a capacity for self-motivated learning and change.[10] This concept of designing the work system with the full participation of the people proved to be a breakthrough for organizations during the 1990s. During that time, employees closest to the product and customer began to have increasing decision making capacities and capabilities.[11]

Interview programs

The Hawthorne Experiments sought to determine a correlation between light levels and productivity. Researchers had divided the employees into teams of six and interviewed the individuals to determine the effect of the lighting. Mayo discovered that the interview program set up by the study inherently gave the employees a sense of higher purpose.[9] Exposure of employee thoughts and concerns to managers appeared to be a fundamental aspect of the relation between managers and employees. Evidently, by having the ability to speak to their managers, the employees at Western Electric exhibited a dramatic improvement in their attitudes towards work.[12] Essential to a highly committed work force, the interview program formally developed and sustained cooperation with management.

Problem-solving teams

The Hawthorne experiment further highlighted that teams working without coercion from above or limitation from below could astonish even their own expectations of themselves. Sociologist Fritz Roethlisberger argued that this informal organization left the team responsible for addressing the myriad of problems that continuously arose. Roethlisberger noted by studying the chemistry of informal groups that human interactions and collaboration have the potential to set when teams have to face problems on their own.[13] Together the individuals of the team strive to improve the processes of the team by adapting to different demands and learning from each other.

Cross training

Cross training began to be heavily examined through the scope of modern Japanese management in the automobile industry in the 1970s. Sociologists examined the way in which the Japanese automobile firms cross-trained its employees through a company wide orientation and training program. As Japanese firms trained their employees in a multitude of aspects in the production process, sociologists discovered that the training brought the employees together and formed a connection in which all the employees were dedicated to the company’s mission.[14] These established connections appeared to solicit cooperation among the work force.[11] The Japanese auto plants revealed that flexibility within the production teams allowed employees to work on their own tasks while keeping others efficient.

Difference from other management strategies

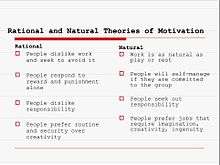

High-commitment practices are spin-offs from the natural system of managements.[15] Like other management strategies in the natural system of management,[16] High-commitment practices assume natural theories of motivation [15] rather than the considerably different rational theories of motivation.[15]

Because most management strategies before High Commitment practices assumed rational theories of motivation, high-commitment practices differ from these strategies in three primary aspects.

Employee motivation

In terms of methods of motivating workers, differences between High Commitment Practices and strategies from the rational system of management are extreme. The rational system of management focuses on either punishments or incentives.[15] For example, the earliest form of rational management, direct control, encourages employee productivity by having supervisors oversee the production process and punish workers who are not producing enough outputs.[17] Another form of rational management, bureaucratic control, encourages productivity through career incentives like bonuses and promotions. However, High Commitment Practices, unlike any rational management, aim to stimulate productivity by encouraging employee commitment to the institution.[18] For example, Data General, a corporation which advocates High Commitment Practices, manages to make employees love their tasks and grow attached to the corporation so much that many employees elect to work twelve hours, four more than Data General prescribes.[19] Contrary to rational management, High Commitment Practices attempt to create scenarios in which employees aspire to deliver their best efforts.

Employee control

High Commitment Practices also differ from practices in the rational management system with regards to employee control. The rational system of management discourages job autonomy, believing that such freedom will only lower productivity because employees will elect not to work. For example, in scientific management and Fordism,[20] employees are micro-managed- they are given specific instructions on how to perform certain tasks. However, High Commitment Practices encourage job autonomy, creativity, and innovation,[18] all of which institutions with High Commitment Practices believe will increase job satisfaction and commitment leading to increased outputs. While the rational system of management attempts to micro-manage employees, High Commitment Practices greatly encourage independence.

Influence on corporate structure

With respect to corporate structure, institutions employing rational management and institutions employing high commitment practices also differ. Institutions with rational management tend to have a steep hierarchy with many ranks between floor-workers and executives.[21] For example, institutions employing bureaucratic control often have one entry level at the bottom of the hierarchy, and new recruits slowly work their ways up the seemingly endless ladder. Because these institutions have a steep hierarchy, those near the bottom of the chain are often alienated from higher ups[22] Consequently, relationship between executives and workers are minimal. However, institutions which employ High Commitment Practices have fairly flat hierarchy and intra-firm networking is easy. As a result, most employees readily develop attachment to their on-job peers, bosses, and the institution, increasing their commitment. While the rational system of management maintains distance between executive and lower employees, High Commitment Practices foster good relationship between the two.

Other natural managements

While high-commitment practices are similar to other strategies in the system, particularly the Human Relations School, in terms of the three aspects previously discussed, their goals are different. Although both attempt to increase job satisfaction and make employees feel valued, High Commitment Practices seek to make employees feel attached to their institutions while the Human Relations School simply seek to make employees aspire to work because of the satisfaction gained from contributing outputs.[18]

With the significant shift in the way firms are motivating their employees in recent years, many companies are beginning to realize that having a “strong corporate culture” is an important ingredient in organizational success. Employee commitment is “replacing traditional controls such as direct supervision and bureaucratic arrangements.” [3] No longer do these high commitment workplaces rely on their CEOs to force the workers to produce, but instead, these workers are self-motivated to bring their best to the company.

One company that follows this high commitment model is Google. A little over a decade ago, Google was an unknown. Today, Google not only refers to the multinational corporation which provides Internet-related products and services, but it has also become a common verb many use every day—“just Google it.” What sets Google apart from many companies, however, is its unique corporate culture. Founded in 1998 by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the two men wanted Google to be a place where people would enjoy work. The company’s philosophies, which include principles such as “work should be challenging and the challenge should be fun” and “you can be serious without a suit”, are consistent with its innovative and informal environment.[23]

In terms of organization, Google maintains “a casual and democratic atmosphere, resulting in its distinction as a ‘Flat’ company.”[24] In its earlier years, Google had a fairly informal product-development system. Ideas moved upwards from “Googlers” without any formal review process from senior managers, and teams working on innovative projects were kept small. However, with the continuing expansion of the company, Google now holds weekly, all-hands (‘TGIF’) meetings at which employees ask questions directly to Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and other executives about any number of company issues. This is consistent with the idea that high commitment work systems “typically involve practices that enhance communication across organizational levels.” [25] In addition, employees are encouraged to propose wild, ambitious ideas, and supervisors are assigned small teams to test if these ideas will work. Teams are made up of members with equal authority—“there is no top-down hierarchy”—and nearly everyone at Google carries a generic job title, such as “product manager.” [24]

Google hires those who are “smart and determined,” and it favors “ability over experience.” [26] In an interview on the company’s corporate culture and hiring, Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, stressed the importance of evaluating potential hires’ passions and commitments in addition to their technical qualifications. He said that “people are going to do what they’re going to do, and you (company, leader) just assist them.” [27] Google does not believe that its job is to manage the company; instead, it believes that its greatest task is to hire the right people. And once the company has those people, it “will see a building of ‘self-initiative’ behavior”—one of the important characteristics of people working in high commitment workplaces.[28] As a result, all engineers at Google are allotted 20 percent of their time to work on their own ideas—some of which yield public offerings, such as Google News and Orkut, a social networking website.

Implementation difficulties and disadvantages

While there is substantial evidence that high commitment management practices have many benefits to the efficiency and well-being of the workplace as seen above, there are some disadvantages and difficulties found in the system.

Much of the research presenting strong evidence of success with high commitment management practices may actually be due to confounding variables. An example of this can be seen in research by Burton and O’Reilly [29] who suggested that the benefits seen from high commitment practices may not be due to the practices themselves, but may result from on overarching system architecture or organizational logic. Another possibility they suggested was that good managers themselves pick this form of managing practice [29] and therefore good managers may be a confounding variable. Thus it is possible that the relative success of these practices is in fact a result of reasons other than the practices themselves.

In the process of becoming a workplace with high commitment management practices, the transition [30] can be difficult and in order to gain the full benefits of such practices full implementation is required.[31] All companies must go through a transitioning stage from their previous form of management to high commitment management practices, however not all of the changes can be made at once. This transition can often be difficult for managers to find the right balance between enough and too much worker influence [30] and change the management philosophy along with the practices.[32] Full implementation of high commitment management practices is required in order to receive the full benefits of the system,[33] and therefore during the transition period firms may not experience positive changes right away, which may provide disincentives for continuing the transition. This may explain why very few firms in the US have comprehensive commitment practices.[30]

High-commitment management practices are currently considered a universal approach [34] seen to be effective in all firms, however the best form of management for a firm with a price-sensitive, high-volume commodity market will differ from a firm with a high-quality, low-volume market.[33] This has been seen within the private and public sectors, where only some high-commitment management practices in the private sector have the same benefits in the public sector and the entire program cannot be transported.[35] Managers may also face difficulty when implementing high commitment management practices as they face a tension between a consistent approach using the same practices throughout the entire workforce or adjusting their practices based on specific needs of different groups.[34] As workforces become more diverse, this tension may become more pronounced.

While it has been proven that workers feel positively towards high commitment management practices, it is also admitted that these practices portray workers as a resource or commodity that will be exploited by the organization.[36] Therefore, even though positive effects have been shown, these practices are also seen as another management initiative to try to gain greater control and efficiency from employees.[32] Therefore, these practices are still exploiting the worker. Workers do express excessive pressure [32] and high insecurity [37] when high commitment management practices are implemented. However, even though companies may have high commitment practices, which in itself mean companies will have little employee flexibility, if the nature of the company is such that they embrace change, then it is possible for these to coexist.

Therefore, while there are many benefits proven to exist as a result of high commitment management practices, there are also disadvantages and difficulties incurred by management.

References

- 1 2 Wesenberg, Sean. Phone Interview. 18 November 2012

- ↑ Beer, Michael and Russell A. Eisenstat. High Commitment, High Performance: How to Build a Resilient Organization for Sustained Advantage. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009. Print.

- 1 2 3 Lowe, Jim, and Nick Oliver. "The High Commitment Workplace: Two Cases from a Hi-Tech Industry." Work, Employment & Society 5.3 (1991): 437-50. Print.

- ↑ Lowe, Jim, and Nick Oliver. "The High Commitment Workplace: Two Cases from a Hi-Tech Industry." Work, Employment & Society 5.3 (1991): 437-50. Print

- ↑ Wesenberg, Sean. Phone Interview. 18 November 2012)

- ↑ Beer, Michael and Russell A. Eisenstat. High Commitment, High Performance: How to Build a Resilient Organization for Sustained Advantage. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009. Print

- ↑ Beer, Michael (2009). High Commitment, High Performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- ↑ Foote, Nathaniel. "High Commitment, High Performance Management” HBS Working Knowledge. Harvard Business School, 10 August 2009. Web. 15 Nov. 2012. <http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6119.html>.

- 1 2 Mayo, Elton 1984 [1949]. ― Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company.‖ Pp. 279-292 in Organization Theory: Selected Readings. Second Edition. Edited by D.S. Pugh. New York: Penguin.

- ↑ Mayo, Elton 1984 [1949]. ―Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company.‖ Pp. 279-292 in Organization Theory: Selected Readings. Second Edition. Edited by D.S. Pugh. New York: Penguin.

- 1 2 Hunter, Larry W., and Lorin M. Hitt. "What Makes a Committed Workplace?" Wharton Business School. University of Pennsylvania, 24 July 2002. Web. 15 Nov. 2012. <http://fic.wharton.upenn.edu/fic/papers/00/0030.pdf>.

- ↑ Mifflin, Jeffrey. "Western Electric Company. Hawthorne Studies Collection, 1924-1961 (inclusive): A Finding Aid." Western Electric Company. Hawthorne Studies Collection, 1924-1961 (inclusive): A Finding Aid. Harvard Business School, 04 Jan. 1998. Web. 16 Nov. 2012. <http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~bak00047>.

- ↑ Roethlisberger, Fritz J. and William J. Dickson. 1981 [1939]. ―Human Relations.‖ Pp. 67-83 in The Sociology of Organizations: Basic Studies. Second Edition. Edited by O. Grusky and G. A. Miller. New York: Free Press.

- ↑ Graham, Laurie 1993. ―Inside a Japanese Transplant: A Critical Perspective.‖ Work and Occupations. 20(2):147-173.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frank Dobbin, “From Incentives to Teamwork: Rational and Natural Management Systems” (Sociology 25, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 1 October 2012).

- ↑ E. Mayo.'Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company'.The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilization. Routledge, 1949. chapter 4. pp. 60-76.

- ↑ Frank Dobbin, “Managing the Workforce” (Sociology 25, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 17 September 2012).

- 1 2 3 Frank Dobbin, “High Commitment Practices” (Sociology 25, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 10 October 2012).

- ↑ Tracy Kidder, The Soul of a New Machine, 1981

- ↑ Taylor, Federick W. "Scientific Management." CLASSICAL THEORETICAL PERSPECTlVES : 54-66. Print.

- ↑ Frank Dobbin, “Internal Labor Market” (Sociology 25, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 14 September 2012).

- ↑ Frank Dobbin, “Alienation” (Sociology 25, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 19 September 2012).

- ↑ "Ten Things We Know to Be True." Google Company. Google, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2012. <https://www.google.com/about/company/philosophy/>.

- 1 2 Johansson, Greg. "Google: The World's Most Successful Corporate Culture." Weblog post.Suite 101. N.p., 29 May 2010. Web. 17 Nov. 2012.

- ↑ Burton, M. Diane, and Charles O'Reilly. Walking the Talk: The Impact of High Commitment Values and Practices on Technology Start-ups. Rep. N.p.: n.p., 2004. Print.

- ↑ "Our Culture." Google Company. Google, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2012. <https://www.google.com/ about/company/facts/culture/>

- ↑ Schmidt, Eric. "Corporate Culture Example: Google’s Eric Schmidt On Culture & Hiring." Interview. Weblog post. Culture Matters: Corporate Culture Pros Blog. Corporate Culture Pros, 6 July 2011. Web. 17 Nov. 2012. <http://www.corporateculturepros.com/2011/07/corporate-culture-example-google-hiring/>.

- ↑ Schmidt, Eric. "Corporate Culture Example: Google’s Eric Schmidt On Culture & Hiring." Interview. Weblog post. Culture Matters: Corporate Culture Pros Blog. Corporate Culture Pros, 6 July 2011. Web. 17 Nov. 2012. <http://www.corporateculturepros.com/2011/07/corporate-culture-example-google-hiring/>.).

- 1 2 Burton, Diane O’Reilly, Charles. “Walking the Talk: The Impact of High Commitment Values and Practices on Technology Start-ups”, 14 August 2004.

- 1 2 3 Walton, Richard. “From Control to Commitment in the Workplace”, ‘’Chapter 10’’. September 19, 2002.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Sue Purcell, John Kinnie, Nick. “Evolving High Commitment Management and Experience of the RAC Calling Centre”, ‘’Human Resource Management Journal’’, January 2000.

- 1 2 3 Guest, David. “Human Resource Management – The Workers’ Verdict”, ‘’Human Resource Management Journal’’, July 1999.

- 1 2 Hutchinson, Sue Purcell, John Kinnie, Nick. “Evolving High Commitment Management and Experience of the RAC Calling Centre”, Human Resource Management Journal, January 2000.

- 1 2 Kinnie, Nicholas et al. “Satisfaction with HR Practices and Commitment to the Organisation: Why one size does not fit all”, Human Resource Management Journal. November 2005.

- ↑ Gould-Williams, Julian. “The Effects of ‘High Commitment’ HRM Practices on Employee Attitude: The Views of Public Sector Workers”, ‘’Public Administration’’, March 2004

- ↑ Grant, David Shields, John. “In Search of the Subject: Researching Employee Reactions to Human Resource Management”, ‘’The Journal of Industrial Relations’’, September 2002.

- ↑ Lowe, Jim Oliver, Nick “The High Commitment Workplace: Two Cases from a High-Tech Industry”, ‘’Work, Employment and Society’’, September 1, 1991.