Hakuun Yasutani

| Hakuun Yasutani | |

|---|---|

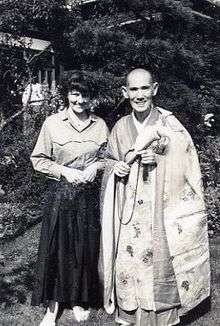

Yasutani Rōshi and Brigitte D'Ortschy | |

| Religion | Zen Buddhism |

| School | Sanbo Kyodan |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Born |

1885 Japan |

| Died | 1973 |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Rōshi |

| Predecessor | Harada Daiun Sogaku |

| Successor |

Yamada Koun Taizan Maezumi |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Persons Chán in China

Zen in Japan Seon in Korea Zen in the USA Category: Zen Buddhists |

|

Awakening |

|

Practice |

|

Related schools |

| Part of a series on |

| Western Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Main articles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Buddhism

|

Hakuun Yasutani (安谷 白雲 Yasutani Haku'un, 1885–1973) was a Sōtō Rōshi, the founder of the Sanbo Kyodan Zen Buddhist organization.

Biography

Ryōkō Yasutani (安谷 量衡) was born in Japan in Shizuoka Prefecture. His family was very poor, and therefore he was adopted by another family.[1] When he was five he was sent to Fukuji-in, a small Rinzai-temple under the guidance of Tsuyama Genpo.[1]

Yasutani saw himself becoming a Zen-priest as destined:

There is a miraculous story about his birth: His mother had already decided that her next son would be a priest when she was given a bead off a rosary by a nun who instructed her to swallow it for a safe childbirth. When he was born his left hand was tightly clasped around that same bead. By his own reckoning, "your life ... flows out of time much earlier than what begins at your own conception. Your life seeks your parents.[1]

Yet his chances to become a Zen-priest were small, since he was not born into a temple-family.[2]

When he was eleven he moved to Daichuji, also a Rinzai-temple.[1] At the age of thirteen he was ordained at Teishinji,[1] a Sōtō temple and given the name Hakuun.[3] When he was sixteen he moved again, to Denshinji, under the guidance of Nishiari Bokusan Zenji.[1]

Thereafter he studied with several other priests, but was also educated as a schoolteacher and became an elementary school teacher and principal. When he was thirty he married, and his wife and he eventually had five children.[1]

He began training in 1925, when he was forty, under Harada Daiun Sogaku, a Sōtō Rōshi who had studied Zen under both Sōtō and Rinzai masters. Two years later he attained kensho, as recognized by his teacher. He finished his koan study when he was in his early fifties, and received Dharma transmission from Harada in 1943, at age fifty-eight.[4] He was head of a training-hall, but gave this up, preferring instead to train lay-practitioners.[1]

To Yasutani's opinion Sōtō Zen practice in Japan had become rather methodical and ritualistic.[5] Yasutani felt that practice and realization were lacking. He left the Sōtō-sect, and in 1954, when he was already 69, established Sanbō Kyōdan (Fellowship of the Three Treasures), his own organization as an independent school of Zen.[4] After that his efforts were directed primarily toward the training of lay practitioners.

Yasutani first traveled to United States in 1962 when he was already in his seventies. He became known through the book The Three Pillars of Zen, published in 1965.[6] It was compiled by Philip Kapleau, who started to study with Yasutani in 1956. It contains a short biography of Yasutani and his Introductory Lectures on Zen Training. The lectures were among the first instructions on how to do zazen ever published in English. The book also has Yasutani's Commentary on the Koan Mu and somewhat unorthodox reports of his dokusan interviews with Western students.[7]

In 1970 upon his retirement Yasutani was succeeded as Kanchõ (superintendent) of the Sanbokyodan sect by Yamada Kõun. Hakuun Yasutani died on 8 March 1973.[8]

Teaching style

The Sanbõ Kyõdan incorporates Rinzai Kōan study as well as much of Soto tradition, a style Yasutani had learned from his teacher Harada Daiun Sogaku.

Yasutani placed great emphasis on kensho, initial insight into one's true nature,[9] as a start of real practice:[1][note 1]

Yasutani was so outspoken because he felt that the Soto sect in which he trained emphasized the intrinsic, or original aspect of enlightenment — that everything is nothing but Buddha-nature itself — to the exclusion of the experiential aspect of actually awakening to this original enlightenment.[1]

To attain kensho, most students are assigned the mu-koan. After breaking through, the student first studies twenty-two "in-house"[10] koans, which are "unpublished and not for the general public".[10] There-after, the students goes through the Gateless Gate (Mumonkan), the Blue Cliff Record, the Book of Equanimity, and the Record of Transmitting the Light.[10]

Political views

Nationalist political views

According to Ichikawa Hakugen, Yasutani was "a fanatical militarist and anti-communist".[11] Brian Victoria, in his book Zen at War, places this remark in the larger context of the Meiji Restoration, which began in 1868. Japan then left its mediaeval feudal system, opening up to foreign influences and modern western technology and culture. In the wake of this process a fierce nationalism developed. It marked the constitution of the Empire of Japan, rapid industrial growth, but also the onset of offensive militarism, and the persecution of Buddhism.[12] In reaction to these developments, Japanese Buddhism developed Buddhist modernism,[13][14] but also support for the autocratic regime, as a means to survive.[12][14] Victoria also suggests that Yasutani was influenced by Nazi propaganda he heard from Karlfried Graf Dürckheim during the 1940s.[15]

Victoria has sequeled his Zen at War with more research. He has directed attention to Yasutani's Zen Master Dogen and the Shushogi (Treatise on Practice and Enlightenment), published in 1943.[web 1] This book is "a rallying cry for the unity of Asia under Japanese hegemony":[web 2]

Annihilating the treachery of the United States and Britain and establishing the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere is the only way to save the one billion people of Asia so that they can, with peace of mind, proceed on their respective paths. Furthermore, it is only natural that this will contribute to the construction of a new world order, exorcising evil spirits from the world and leading to the realization of eternal peace and happiness for all humanity. I believe this is truly the critically important mission to be accomplished by our great Japanese empire.

In fact, it must be said that in accomplishing this very important national mission the most important and fundamental factor is the power of spiritual culture.[web 2]

Responses

Victoria's treatment of the subject has stirred strong reactions and approval:

Few books in recent years have so deeply influenced the thinking of Buddhists in Japan and elsewhere as Brian Daizen Victoria’s Zen at War (Victoria 1997). The book’s great contribution is that it has succeeded, where others have not, in bringing to public attention the largely unquestioning support of Japanese Buddhists for their nation’s militarism in the years following the Meiji Restoration in 1868 (when Japan opened its borders after nearly 250 years of feudal isolation) up until the end of WWII.[16]

To Bodhin Kholhede, dharma heir of Philip Kapleau, Yasutani's political views raise questions about the meaning of enlightenment:

Now that we’ve had the book on Yasutani Roshi opened for us, we are presented with a new koan. Like so many koans, it is painfully baffling: How could an enlightened Zen master have spouted such hatred and prejudice? The nub of this koan, I would suggest, is the word enlightened. If we see enlightenment as an all-or-nothing place of arrival that confers a permanent saintliness on us, then we’ll remain stymied by this koan. But in fact there are myriad levels of enlightenment, and all evidence suggests that, short of full enlightenment (and perhaps even with it—who knows?), deeper defilements and habit tendencies remain rooted in the mind.[web 3]

Criticism

But Victoria has also been criticized for a lack of accuracy in his citation and translation of texts from the persons he accuses.[16][web 4]

Robert Baker Aitken writes:

Unlike the other researchers, Victoria writes in a vacuum. He extracts the words and deeds of Japanese Buddhist leaders from their cultural and temporal context, and judges them from a present-day, progressive, Western point of view.[web 5]

Bernie Glassman writes:

As a Jew, I never picked up a hint of bigotry against the West in general or against Jews in particular.[web 6]

Apologies

The book also led to a campaign by a Dutch woman who was married with a war victim:

The main reason the Dutch lady raised the question is that she had read Brian Victoria's book Zen at War and felt herself betrayed by the war-time words and deeds of the founder of the Sanbô Kyôdan Yasutani Haku'un Roshi, who repeatedly praised and promoted the war.[web 7]

Kubota Ji'un, "the 3rd Abbot of the Religious Foundation Sanbô Kyôdan"[web 7] acknowledges Yasutani's right-wing sympathies:

Yasutani Roshi did foster strongly right-winged and anti-Semitic ideology during as well as after World War II, just as Mr. Victoria points out in his book.[web 7]

Eventually, in 2000, Kubota Ji'un issued an apology for Yasutani's statements and actions during the Pacific War:

If Yasutani Roshi's words and deeds, now disclosed in the book, have deeply shocked anyone who practices in the Zen line of the Sanbô Kyôdan and, consequently, caused him or her to abhor or abandon the practice of Zen, it is a great pity indeed. For the offense caused by these errant words and actions of the past master, I, the present abbot of the Sanbô Kyôdan, cannot but express my heartfelt regret.[web 7]

Influence

As founder of the Sanbo Kyodan, and as the teacher of Taizan Maezumi, Yasutani has been one of the most influential persons in bringing Zen practice to the west. Although the membership of the Sanbo Kyodan organization is relatively small (3,790 registered followers and 24 instructors in 1988[14]), "the Sanbõkyõdan has had an inordinate influence on Zen in the West",[14] and although the White Plum Asanga founded by Taizan Maezumi is independent of the Sanbo Kyodan, in some respects it perpetuates Yasutani's influence.

| Soto lineage Soto school |

Rinzai lineage Rinzai school |

|||||

| Harada Sodo Kakusho (1844-1931)[web 8] | Dokutan Sosan (a.k.a. Dokutan Toyota) (1840-1917)[web 8] | Rinzai lineage Rinzai school | ||||

| Harada Daiun Sogaku (1871-1961)[web 8] | Soto lineage Soto school |

Joko Roshi [web 9][note 2] | ||||

| Hakuun Yasutani[web 8] | Hakuun Yasutani[web 8] | Baian Hakujun Kuroda | Koryu Osaka (1901-1985) | |||

|

Philip Kapleau (1912-2004) | Yamada Koun (1907-1989) | Taizan Maezumi (1931-1995) | |||

|

|

| ||||

Bibliography

- Yasutani, Hakuun; Jaffe, Paul (1996), Flowers Fall: A commentary on Zen Master Dogen's Genjokoan, Shambala, ISBN 1-57062-103-9

- Dōgen Zenji to Shūshōgi (道元禅師と修證義). Tōkyō: Fujishobō, 1943

See also

- Buddhism in Japan

- Buddhism in the United States

- Buddhism in the West

- Timeline of Zen Buddhism in the United States

Notes

- ↑ This is in line with Rinzai-Zen, which emphasizes kensho, but does not regard this to be the end of the way. See Three mysterious Gates, and the Four Ways of Knowing

- ↑ Bernie Glassmann: "Koryu roshi’s school was called Shakyamuni Kai. The Shakyamuni Kai was formed by Koryu roshi’s teacher, a man named Joko roshi; Joko roshi was actually a priest and teacher in few different Buddhist traditions."[web 9] A group with a similar name was the Shakuson Shōfu Kai, or "Shakyamuni True Way Society", founded by Kōnen Shaku (1849-1924), a student of Soyen Shaku.[17]

References

Book references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jaffe 1979.

- ↑ Ford 2006, p. 150.

- ↑ Kapleau 1989, p. 30.

- 1 2 Jaffe 1996, p. xxiv.

- ↑ Jaffe 1996, p. xxviii.

- ↑ "Zen Teaching, Zen Practice: Philip Kapleau and The Three Pillars of Zen". thezensite. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

First published in 1965, it has not been out of print ever since, has been translated into ten languages and, perhaps most importantly, still inspires newcomers to take up the practice of Zen Buddhism.

- ↑ Jaffe 1996, p. xxv.

- ↑ Sharf, Robert, H. (1995). "Sanbokyodan. Zen and the Way of the New Religions" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 22 (3-4): 422. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2000.

- ↑ Sharf 1995c.

- 1 2 3 Ford 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Victoria 2006, p. 167.

- 1 2 Victoria 2006.

- ↑ mcMahan 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Sharf 1993.

- ↑ Brian Daizen Victoria, Zen War Stories, Volume 21 of Routledge Critical Studies in Buddhism; Psychology Press, 2003; p. 88; ISBN 978-0700715817.

- 1 2 Sato 2008.

- ↑ Morrow 2008, p. 2.

Web references

- ↑ "Tricycle, fall 1999, ''Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan, Part 1''". Tricycle.org. Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- 1 2 "Tricycle, fall 1999, ''Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan, Part 2''". Tricycle.org. Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- ↑ "Tricycle, fall 1999, ''Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan, Part 4''". Tricycle.org. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "Koichi Miyata, ''Critical Comments on Brian Victoria's "Engaged Buddhism: A Skeleton in the Closet?"''". Globalbuddhism.org. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ↑ "Tricycle, fall 1999, ''Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan, Part 3''". Tricycle.org. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "Tricycle, fall 1999, ''Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan, Part 5''". Tricycle.org. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- 1 2 3 4 "Apology for What the Founder of the Sanbo-Kyodan, Haku'un Yasutani Roshi, Said and Did During World War II". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sanbo Kyodan: Harada-Yasutani School of Zen Buddhism and its Teachers

- 1 2 Sweeping Zen: Interview with Bernie Glassmann

- ↑ Barthashius, Ruben Keiun-ken Habito

Sources

- Ford, James Ishmael (2006), Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People And Stories of Zen, Wisdom Publications

- Jaffe, Paul David (1979), Yasutani Hakuun Roshi — a biographical note

- Jaffe, Paul David (1996), Foreword. In: Flowers Fall: A commentary on Zen Master Dogen's Genjokoan, Shambala, ISBN 1-57062-103-9

- Kapleau, Philip, ed.and translator (1989), The Three Pillars of Zen, Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-26093-8

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Sato, Kemmyō Taira (2008), D.T. Suzuki and the Question of War (PDF)The Eastern Buddhist 39/1: 61–120

- Sharf, Robert H. (August 1993), "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism", History of Religions, 33 (1): 1–43

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995c), "Sanbokyodan. Zen and the Way of the New Religions" (PDF), Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1995 22/3-4

- Victoria, Brian Daizen (2006), Zen at war (Second ed.), Lanham e.a.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Yasutani, Hakuun; Jaffe, Paul (1996), Flowers Fall: A commentary on Zen Master Dogen's Genjokoan, Shambala, ISBN 1-57062-103-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haku'un Yasutani. |