Groupe de femmes

%2C_plaster_lost%2C_photo_Galerie_Ren%C3%A9_Reichard%2C_Frankfurt%2C_72dpi.jpg) | |

| Artist | Joseph Csaky |

|---|---|

| Year | 1911-12 |

| Type | Sculpture (original plaster). Csaky photographic archives (AC. 109) |

| Location | Dimensions and whereabouts unknown (presumed destroyed) |

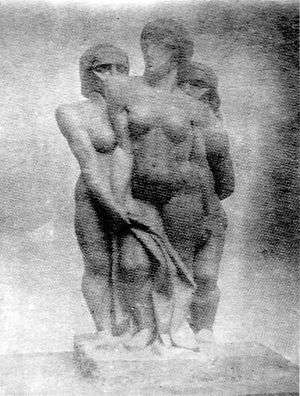

Groupe de femmes, also called Groupe de trois femmes, or Groupe de trois personnages, is an early Cubist sculpture created circa 1911 by the Hungarian avant-garde, sculptor, and graphic artist Joseph Csaky (1888–1971). This sculpture formerly known from a black and white photograph (Galerie René Reichard) had been erroneously entitled Deux Femmes (Two Women), as the image captured on an angle showed only two figures. An additional photograph found in the Csaky family archives shows a frontal view of the work, revealing three figures rather than two. Csaky's sculpture was exhibited at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, and the 1913 Salon des Indépendants, Paris. A photograph taken of Salle XI in sitiu at the 1912 Salon d'Automne and published in L'Illustration, 12 October 1912, p. 47, shows Groupe de femmes exhibited alongside the works of Jean Metzinger, František Kupka, Francis Picabia, Amedeo Modigliani and Henri Le Fauconnier.

At the 1913 Salon des Indépendants Groupe de femmes was exhibited in the company works by Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, André Lhote, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Villon and Wassily Kandinsky.[1]

The whereabouts of Groupe de femmes is unknown and the sculpture is presumed to have been destroyed.

Description

Groupe de femmes is a plaster sculpture (as many of Csaky's works of the period), carved in a vertical format with unknown dimensions. The work represents three standing nudes, classical in theme (i.e., Les trois graces), yet executed in an abstract stylized Cubist vocabulary, in opposition to the softness and curvilinearity of Nabis, Symbolist or Art Nouveau forms.[2]

The dominating central figure is flanked by a woman to her left and another to the right, positioned slightly behind. Two of the women are holding drapery that flows rigidly down to their legs to the base of the sculpture. The figures are constructed with a robust, muscular build, distilled in the form of almost androgynous stature, together forming a tight cohesive mass. The heads and features of the figures, seen in both profile and frontal views, are treated as a series of faceted planar forms that communicated in a strange novel 3-dimensional language; one that at the time broke away from every natural and rational convention.

Albert Elsen characterized Csaky's Head sculpture of 1913 in a way that applies to the heads depicted in Groupe de femmes:

His Head is a brutal asymmetrical reconstruction of the motif that submerges featural identity by a logic of thrusting planar forms. The result, unlike that if Filla, is the redesigning of the head that is no longer dependent upon a frontal confrontation for the most revealing view, and the consistency of this sculptural context discourages trying to project missing features on the blank planes. The blunt force-fulness with which the head is shaped and thrusts in and out suggests that Csaky had looked not only at Picasso's earlier painting and sculpture, but also at African tribal masks whose exaggerated features and simplified design accommodated the need to be seen at a distance and to evoke strong feeling. (Albert Elsen)[2][3]

Csaky's heads of the period partake in the "stylized, hieratic, nonportrait tradition of tribal and ancient art", writes Edith Balas, "in which there is a total lack of interest in depicting psychological traits". Csaky's Groupe de femmes and the Head (1913) "are lost sculptures that testify to Csaky's early immersion in cubism".[2]

History

This works was likely realized at Csaky's studio in La Ruche; the artist enclave of Montparnasse, among many members of the Parisian avant-garde. From the outset of the 20th-century Paris was the art center of the world, where artists came to live and work from all parts of Europe and beyond:[2] Joseph Csaky from Constantin Brâncuși from Hobitza, Amedeo Modigliani from Livorno, Gino Severini from Rome, Alexander Archipenko from Kiev, Ossip Zadkine from Smolensk, Marc Chagall from St. Petersburg, Jacques Lipchitz from Vilna, Piet Mondrian from Amsterdam, Moïse Kisling from Kraków, Pablo Picasso from Barcelona, Louis Marcoussis from Kraków, Chaim Soutine from Vilnius.

During his proto-Cubist phase Csaky had already separated himself from the past. By 1911-12 Csaky participation in the avant-garde milieu was complete. His acquaintances included Gustave Miklos, Archipenko, Braque, Chagall, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Le Fauconnier, Laurens, Léger, Lipchitz, Metzinger, Picasso and Henri Rousseau, in addition to Pierre Reverdy, Maurice Raynal, Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars, Guillaume Apollinaire and Ricciotto Canudo.[2]

After exhibiting Groupe de femmes with the Cubists at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, Grand Palais des Champs Elysées—an exhibition that provoked a succès de scandal, and resulted in a xenophobe and anti-modernist quarrel in the French National Assembly—Csaky exhibited his Cubist works at the Salon de la Section d'Or, Galerie La Boétie, Paris, October 1912; considered one of the high points of the Cubist movement.[2] Csaky was one of the first artists to apply Cubist principles to sculpture; principles that he would never abandon or disavow.[2] Michel Seuphor has written:

Csaky, after Archipenko, was the first sculptor to join the cubists, with whom he exhibited from 1911 on. They were followed by Duchamp-Villon, brother of Marcel Duchamp and of Jacques Villon, and then in 1914 by Lipchitz, Laurens and Zadkine.[2][2][4]

In Groupe de femmes Csaky already showed a new way of representing nature, and the unwillingness to revert to classical, academic or traditional methods of representation. The complex syntax observed in Groupe de femmes was born out of an increasing sense of contemporary dynamism, out of the rhythm, balance, harmony and powerful geometric qualities of Egyptian art, of African art, early Cycladic art, Gothic art, and of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Auguste Rodin, Gustave Courbet, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne.

Csaky wrote of the direction his art had taken during the crucial years:

There was no question which was my way. True, I was not alone, but in the company of several artists who came from Eastern Europe. I joined the cubists in the Académie de La Palette, which became the sanctuary of the new direction in art. On my part I did not want to imitate anyone or anything. This is why I joined the cubists movement. (Joseph Csaky)[2]

Works exhibited at the 1912 Salon d'Automne

- Joseph Csaky exhibited the sculptures Groupe de femmes, 1911-1912 (location unknown), Portrait de M.S.H., no. 91 (location unknown), and Danseuse (Femme à l'éventail, Femme à la cruche) no. 405 (location unknown)

- Jean Metzinger entered three works: Dancer in a café (entitled Danseuse), La Plume Jaune (The Yellow Feather), Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan) (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York), hung in the decorative arts section inside La Maison Cubiste (the Cubist House).

- Francis Picabia, 1912, La Source (The Spring) (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

- Fernand Léger exhibited La Femme en Bleu (Woman in Blue), 1912 (Kunstmuseum, Basel) and Le passage à niveau (The Level Crossing), 1912 (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland)

- Roger de La Fresnaye, Les Baigneuse (The bathers) 1912 (The National Gallery, Washington) and Les joueurs de cartes (Card Players)

- Henri Le Fauconnier, The Huntsman (Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands) and Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours (Mountaineers Attacked by Bears) 1912 (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design).

- Albert Gleizes, l'Homme au Balcon (Man on a Balcony, Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud), 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), also exhibited at the Armory show, New York, Chicago, Boston, 1913.

- André Lhote, Le jugement de Paris, 1912 (Private collection)

- František Kupka, Amorpha, Fugue à deux couleurs (Fugue in Two Colors), 1912 (Narodni Galerie, Prague), and Amorpha Chromatique Chaude.

- Alexander Archipenko, Family Life, 1912, sculpture (destroyed)

- Amedeo Modigliani, exhibited four sculptures of elongated and highly stylized heads

Exhibitions

- Salon d'Automne, Paris, 1 October - 8 November 1912 (not listed in the catalogue but known to have been exhibited from a photograph taken of Salle XI in sitiu at the 1912 Salon d'Automne and published in L'Illustration, 12 October 1912, p. 47).

- Salon des Indépendants (Salon de la Société des Artistes Indépendants), Paris, 1913, listed in the catalogue as Groupe de femmes (plaster).

- Galerie Moos, Geneva, 1920 (no number).

Literature

- René Reichard, Joseph Csaky, Frankfurt, 1988, n. 14.

- Billy Klüver and Julie Martin, Kiki de Montparnasse, Flammarion, 1989, salle XI, rep. p. 47.

- Edith Balas, Joseph Csaky, A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA., 1998, fig. 5, rep. p. 23.

- Félix Marcilhac, József Csáky, Du cubisme historique à la figuration réaliste, catalogue raisonné des sculptures, Les Editions de l'Amateur, Paris, 2007. rep. p. 314 (1912-FM.14)

Related works

-

Early Cycladic art II period, Harp Player, marble, H 13,5 cm, W 5,7 cm, D 10,9 cm, Cycladic figurine, Bronze Age, early spedos type, Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe, Germany

-

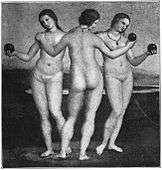

Les Trois Graces, Marble, exhibited at the 1831 Salon. The plaster model was finished by 1825, The Louvre, Paris, Department of Sculptures, Richelieu, ground floor, room 32

-

Raphaël, Les Trois Graces, cited by Auguste Rodin. In L'Art, interview by Paul Gsell, Grasset, 1911, page 265

-

The Three Graces. Copie artwork of the Imperial period after a Greek original of the 2nd century BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

L'Europe de Rubens, Les Trois Grâces

-

Paul Cézanne, Trois baigneuses, 1879-1882, oil on canvas, 42 x 55 cm, Petit Palais, Paris

-

%2C_for_the_top_of_The_Gates_of_Hell%2C_before_1886%2C_plaster.jpg)

Auguste Rodin, The three shades (Les Trois Ombres), for the top of The Gates of Hell, before 1886, plaster

-

%2C_partially_glazed_stoneware%2C_75_x_19_x_27_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Orsay%2C_Paris.jpg)

Paul Gauguin, 1894, Oviri (Sauvage), partially glazed stoneware, 75 x 19 x 27 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Alexander Archipenko, 1912, Le Repos, Armory Show post card, 1913

-

Alexander Archipenko, 1912, La Vie Familiale (Family Life). Exhibited at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, Paris and the 1913 Armory Show in New York, Chicago and Boston. The original sculpture (approx. six feet tall) accidentally destroyed

-

Joseph Csaky, Head (self-portrait), 1913, Plaster lost. Photo published in Montjoie, 1914

-

%2C_marble.jpg)

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1914, Boy with a Coney (Boy with a rabbit), marble

Notes and references

- ↑ Marcilhac, Félix, 2007, Joseph Csaky, Du cubisme historique à la figuration réaliste, catalogue raisonné des sculptures, Les Editions de l'Amateur, Paris

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Edith Balas, 1998, Joseph Csaky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture , American Philosophical Society

- ↑ Albert Edward Elsen, Origins of modern sculpture: pioneers and premises, G. Braziller, 1974

- ↑ Robert Rosenblum, "Cubism", Readings in Art History 2, 1976, Seuphor, Sculpture of this Century, 29

External links

- Canudo, Ricciotto, 1914, Montjoie, text by André Salmon, 3rd issue, 18 March

- Joconde, Portail des Collection des Musée de France, CSAKY Joseph

- Ministère de la Culture, France, La Médiathèque de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine, Base Memoire

- Base Arcade, Culture.gouv.fr Csaky

- The Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands, 23 works by Joseph Csaky