Green Lake (Texas)

| Green Lake | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | Calhoun County, Texas |

| Coordinates | 28°31′43″N 96°50′23″W / 28.5287°N 96.8397°WCoordinates: 28°31′43″N 96°50′23″W / 28.5287°N 96.8397°W |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Surface area | 10,000 acres (40 km2) |

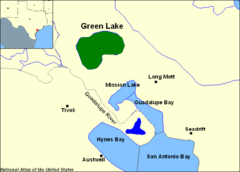

Green Lake is a natural tidal lake in Calhoun County, Texas, on the Guadalupe River flood basin. Known for its greenish waters, from which its name derives, the lake is located 12 miles (19 km) west of Port Lavaca and 22 miles (35 km) south of Victoria on the Gulf Coastal Plain. Despite being less than 3 miles (4.8 km) from the coast of San Antonio Bay, its waters are fresh.[1] It is the largest natural freshwater lake entirely in Texas, covering an area of approximately 10,000 acres (40 km²).[2]

Separated from San Antonio Bay by the Guadalupe River delta around 2,200 years ago, a wetland ecosystem supporting a wide variety of waterfowl developed along the lake shore and the Guadalupe River delta. Archaeological evidence supports claims of Karankawa settlement.

An affluent 19th-century agricultural community of the same name established near the lakeside in the mid-19th century, but dwindled in status, becoming virtually abandoned in the aftermath of the American Civil War. It was strategically important during the early stages of the war, due to its proximity to fresh water and the Gulf of Mexico. After reaching its low point during the Great Depression, the lakeside community modestly rebounded in 1947 following the nearby discovery of oil. A fictional lake of the same name and with a similar history is featured in the 1998 novel Holes.

Hydrology

Green Lake is about 13 miles (21 km) in circumference and about 2 miles (3.2 km) wide.[3] The water level is shallower near the shoreline, but is deepest towards the center of the lake several hundred feet from the shore. The bottom is generally flat and averages about 4 feet (1.2 m) in depth. The nearby Guadalupe River frequently floods the plain, and is the main source of fresh water renewal.[3] The shoreline is naturally grassy and poorly drained with coastal marshes between the lake and San Antonio Bay.[1]

To improve drainage, a levee was constructed in 1967,[4] separating the lake from the Victoria Barge Canal,[5] which runs along the bay's northern and eastern shores; cutting off several bayous from the lake. The canal begins north at an industrial plant outside Victoria and empties in San Antonio Bay in Seadrift. Hog Bayou runs along the western shore of Green Lake, through the Guadalupe Delta Wildlife Management Area to the south, before its confluence with Mission Lake.[6]

History

Formation

Green Lake formed initially as a northern inlet of San Antonio Bay. As the Guadalupe River shifted westward about 2,500 years ago, it deposited silt, developing a delta that prograded into San Antonio Bay. Around 2,200 years ago the delta discharge extended completely across the bay, severing the northern extension from the system, which formed present-day Green Lake. Pottery and burial grounds found in the area suggest a presence of Karankawa Indians at the time of formation. Middens uncovered north of the lake contained shells from the brackish water-species of rangia clams (rangia cuneata).[7]

Settlement

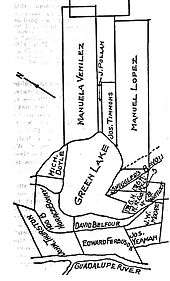

Wealthy cotton farmers from Kentucky established plantations and settled the fertile lands near the lake during the 1850s, establishing the town of Green Lake, Texas. First-hand accounts described it as "the locality of a neighborhood characterized by [the] wealth and social standing of the residents." [8]

After the American Civil War, returning residents found that their slaves, livestock and farm equipment had been taken. Most residents relocated. However, in the early 20th century, farmers returned and the town of Green Lake modestly grew to an approximate population of 300 in 1914.[8] At the time, much of the land in the vicinity was used for livestock grazing. The only profitable commercial uses for the lake itself included transportation of lumber and fishing. Approximately US$100,000 worth of fish were caught in the lake from 1900 to 1915.[9] Nevertheless, the lake bed remained dry for extended periods and vegetation covered certain areas. Local residents soon began to use the bed to grow cotton.[10]

In 1917, Texas filed a trespass to try title suit to reclaim the lake bed for the state. In Welder v. State, the Texas Court of Civil Appeals in Austin declared the lake permanent and navigable-in-fact, granting the bed to the state under the purview of the Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission (later Texas Parks and Wildlife Department).[11] Without permission from the Texas Attorney General, the Texas Land Commissioner then sold the bed to a private buyer for agricultural use in 1918. In the 1948 case of State v. Bryan, the Texas Court of Civil Appeals in Austin upheld the sale as valid under color of law, and immune from a trespass to try title suit due to the one-year statute of limitations on land sales.[12] However, under the Texas Water Rights Adjudication Act of 1967, Green Lake was classified as a public body of water. The Supreme Court of Texas affirmed this classification in 1988, rejecting the argument of the bed's then-owner that it was not a lake by definition, but a natural depression flooded with surface runoff.[13]

During the Great Depression, the population of the Green Lake settlement dwindled to 25. It remained low until the discovery of oil in 1947. Twenty wells were constructed at the Green Lake oilfield, although as of 1984, only one still operated. By 2000, the population of Green Lake was 51, the same number reported in 1970 and 1990.[8]

Civil War

The lake played a role in the evacuation of federal troops from Texas at the onset of the American Civil War. As Texas considered whether to secede from the United States, General David E. Twiggs, commander of federal troops in Texas negotiated with state leaders concerning the transfer of federal property. After learning of such negotiations, the United States military moved to decommission Twiggs, and replace him with Colonel Carlos Waite. Texas viewed this move as a rejection of the negotiations and proceeded to forcefully claim the federal property. Twiggs, while awaiting relief from Waite, surrendered the property on the condition that federal troops could peacefully evacuate. They were allowed to depart, but only from the Texas coast. Waite arrived and relocated troops near Green Lake, where they could await coastal departure near an adequate source of freshwater. During the stay, Fort Sumter fell under siege, and Texas grew concerned about the concentration of armed federal troops in the area. With their respective nations now at war, Texas considered the deal with Twiggs void, and began to capture federal troops to force them to either join the Confederacy or be Prisoners of War. Some of the remaining uncaptured companies elsewhere in the state attempted to flee to Green Lake.[14] Several regiments camped by the lake later in the war, and complained about mosquitos.[15]

Flora and fauna

In the area around Green Lake there are forests of pecan, black willow, cedar, American elm, hackberry and green ash. To the south, the Guadalupe Delta Wildlife Management Area serves as a wetland habitat for thousands of permanent egrets, and other birds,[2] including the brown pelican, reddish egret, white-faced ibis, wood stork, bald eagle, white-tailed hawk, peregrine falcon, and the whooping crane. American alligators reside in the area as well.[16]

Redfish and trout were once the main species of fish living in the lake, until the construction of an embankment reduced their populations. A large quantity of silt is now deposited in the lake from the Guadalupe River, after the dredging of a freshwater channel that supplies farmers and the Union Carbide plant in Seadrift. The channel has negatively affected the delta ecosystem by diminishing the river's nutritional input.[17]

In popular culture

Green Lake, Texas is the setting for Louis Sachar's 1998 novel Holes, and the 2003 film adaptation. It is described as a dry lake that had once been the largest in the state, surrounded by an affluent community. After a long drought, the lake dried up and the area became a ghost town. Juvenile delinquents were sent to Camp Green Lake to dig holes in the lakebed as punishment.[18]

References

- 1 2 "Green Lake". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. May 30, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- 1 2 "Texas Independence Trail", p. 98

- 1 2 "Welder v. State", p. 869

- ↑ McGillicuddy, Ryan (July 2009). "What Makes a Lake" (PDF). Texas Wetland News. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ↑ Roell, Craig H. (May 30, 2010). "Victoria County". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Topographic Maps". Digital-Topo-Maps.com. Google. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Life at Guadalupe Bay". Texas Beyond History. University of Texas. March 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Rupert, Rebecca (May 30, 2010). "Green Lake, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Welder v. State", pp. 869

- ↑ "State v. Bryan", pp. 460-61

- ↑ "Welder v. State", pp. 868–873

- ↑ "State v. Bryan", pp. 455-463

- ↑ "Indianola Co. v. Texas Water Com'n", pp. 72

- ↑ Speer, pp. 2–4

- ↑ Penn, p. 230

- ↑ "Guadalupe Delta WMA". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. August 21, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ↑ Patoski, Joe Nick (December 18, 2003). "The Dead Zone – Water -". San Antonio Current. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ↑ Sachar, pp. 3–5

Bibliography

- "Indianola Co. v. Texas Water Com'n". The Southwestern Reporter. West Pub. Co. 1988.

- Penn, Lyon William (July 2009). Reminiscences of the Civil War. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 978-1-113-21498-0.

- Sachar, Louis (1998). Holes. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR). ISBN 0-374-33266-5.

- "State v. Bryan". The Southwestern Reporter. West Pub. Co. 1948.

- Speer, Lonnie R. (November 1, 2005). Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9342-7.

- "Texas Independence Trail". Texas Monthly. Emmis Communications. 19 (4). April 1991. ISSN 0148-7736.

- "Welder v. State". The Southwestern Reporter. West Pub. Co. 1917.