Great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50

The great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50 was a series of witch trials in Scotland. It is one of five major hunts identified in early modern Scotland and it probably saw the most executions in a single year.

The trials occurred in a period of economic, political and religious unrest. Political and religious turmoil was caused by defeat for the Scottish army in the Second English Civil War and the rise to power of the radical Kirk party, who attempted to create a "godly society", rooting out witches and other offenders. They passed a new Witchcraft Act in 1649 and encouraged local presbyteries to seek out witches. The intense period of witch hunting began in 1649 and continued into 1650, being largely confined to the Lowlands, particularly Lothian and Fife, but spilled over into northern England, where Scottish witch prickers were active. The period of rule by the Kirk party ended when Cromwell led an army across the border in July 1650. Some 612 records of accusations of witchcraft are known for Scotland in the years 1649 and 1650 and over 300 witches were executed in the trials. Most of these were in ad hoc courts that had a much higher execution rate than those run by professional lawyers. Most of the witches were women and most of these of relatively low social status. The Devil featured relatively rarely in witchcraft trials, which were mainly concerned with perceived harm through witchcraft.

Most of the trials were initiated by the local minister and his session or consistory, who aimed to obtain proof or a confession from the accused person. Accused witches would often name other persons who were then tested for the crime, widening the hunt. The Chancellor, John Campbell, 1st Earl of Loudoun expressed reservations about these confessions. In the later stages of the hunt the Parliament and its representative body the Committee of Estates supervised the trials more closely, and instead of issuing commissions of judiciary to local gentlemen, it began to send Sheriff Deputes to hold special justice courts in the localities. After 1650 witch trials entered a new phase, with a reduction in the total number of trails and the abandonment of local trials in favour of mixed central-local trials. Scottish witchcraft trials were notable for their use of pricking of a Devil's mark through which they could not feel pain. This process could turn into a form of torture in which a subject could be repeatedly pricked until they confessed.

Background

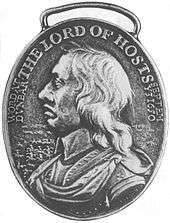

The 1640s were among the coolest decades in the Little Ice Age and the period 1649–53 was one of poor harvests and general scarcity in Scotland.[1] The last outbreak of the bubonic plague in Scotland was in 1644–49.[2] In 1648 the Scottish Covenanter regime had been defeated by the forces of the New Model Army under Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Preston in the Second English Civil War. In early 1649 King Charles I was executed by the English parliament and, when the Scots immediately declared his son king as Charles II, a renewed war between Scotland and the fledgeling English republic looked unavoidable.[3] These circumstances led to the fall of the moderate Engagers, who were willing to engage and compromise with Royalism, and the rise of the Kirk party, the more radical wing of the Presbyterian movement. Its power was consolidated by the passage of the Act of Classes in January 1649, which excluded Engagers from office. The Kirk party was unwilling to compromise on Covenanter principles and aimed to purge Scotland to create a "godly society".[4]

Through the 1640s the General Assembly and the Commission of the Kirk lobbied for the enforcement and extension of the Witchcraft Act 1563, which had been the basis of previous witch trials. The Covenanter regime passed a series of acts to enforce godliness in 1649, which made capital offences of blasphemy, the worship of false gods and for beaters and cursers of their parents. They also passed a new witchcraft act that ratified the existing act and extended it to deal with consulters of "Devils and familiar spirits", who would now be punished with death.[5] In 1649 the commission of the General Assembly co-ordinated presbyteries in their pursuit of "fugitive witches", reminding them of the importance of hunting witches and encouraged them when obtaining commissions of justiciary to recommend the names of commissioners.[6] By May 1650 Parliament had a committee in place to deal with depositions and other legal papers connected to accusations and commissions. Individual members of parliament and other leading Covenanters took a proactive role in witch hunts.[5] In July 1650 Cromwell led an army of 16,000 over the border at Berwick and moved towards Edinburgh, taking control of the Lowlands and eventually winning the decisive victory at Dunbar in September that brought the rule of the Kirk party to an end.[7]

Nature of the hunt

Extent

The hunt of 1649–50 is one of five major witch-hunts in early modern Scotland, the others being in 1590–91, 1597, 1628–31 and 1661–62.[8] There is one surviving and dated accusation for February 1649, a brewer in Dunfermine who successfully defended himself against a charge of using magic, perhaps to enhance his beer. There were two cases for March, three for April, 15 for May and by June the hunt was in full swing,[9] continuing into mid-1650 when it began to subside.[10] Like most of the major series of hunts in Scotland, it was largely confined to the Lowlands,[11] where the Kirk had most control.[12] It began in Lothian and spread to Fife and then throughout the Lowlands.[13] The hunt probably began at Inverkeithing where the minister Walter Bruce demonstrated an interest in witch hunting, being suspended for preaching at the execution of a witch in March 1649. This interest seems to have spread to neighbouring parishes.[14] In addition to Inverkeithing there were major trials at Aberdour, Burntisland, Dysart and Dunfermline.[15] The hunt spilled over into northern England, where a cluster of trials took place in the towns of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Berwick-upon-Tweed as well as in the surrounding villages in Northumberland, in which Scottish witch hunters were involved.[16]

Some 612 records of accusations of witchcraft are known for Scotland in the years 1649 and 1650. Of these most, 399, are from 1649. They include 556 named persons and another 243 unnamed persons.[17] According to Christine Larner, 1649 was "the year which may have seen the greatest number of executions in the whole of Scottish witch-hunting".[5] More than 300 witches were executed in the trials,[18] with as many as 200 executions in Lothian alone.[19] The Newcastle witch trials involved 30 persons, claiming 20 victims, and was the last intense hunt in England.[16] Most of the prosecutions in Scotland were in local ad hoc courts that had a much higher execution rate than the courts run by professional lawyers; local courts executed some 90 per cent of the accused over the entire period, the Judiciary Court 55 per cent, but the circuit courts only 16 per cent.[20]

Accusations

Most of the witches were women, the majority of whom were of relatively low social status. The only high-status woman known to have been accused in the hunt was Margaret Henderson, Lady Pittadro, who was accused by Walter Bruce the minister of Inverkeithing in 1649. She fled to Edinburgh, where she was arrested and probably committed suicide before her trial. Such accusations were usually linked to local power struggles and usually unsuccessful as the families of the accused had reputations to defend and resources to mount a legal and political challenge.[21] Mentions of the Devil appeared relatively rarely in Scottish witchcraft trials, which were mainly concerned with perceived harm through witchcraft, as with Jean Craig of Tranent, who was accused of laying an illness on Beatrix Sandilands, causing her to become "mad and bereft of her naturall wit".[22] Divination was also a common accusation, often with lesser penalties, like the case of Marjorie Plumber, who was debarred from the sacrament by the presbytery of Cullen in Banffshire in 1649 for trying to determine if her ailing child would live by laying it between two holes, a "living grave" and a "dead grave", and seeing which way it turned.[23] However, there were total of 69 confessions of demonic pacts in the court records[24] and the Devil was an important figure in the Inverkeithing hunt, where several women confessed to associations with the Devil, renouncing their baptism and even to having sexual intercourse with him. As a result of these confessions five women were rapidly executed in 1649.[25]

Legal procedures

Most of the hunts were initiated by the local minister and his session or consistory, who aimed to obtain proof or a confession from the accused person. If a confession was forthcoming then a commission was sought, which would usually empower the gentlemen of the district, leading to a trial of the accused. Accused witches would often name other persons who were then tested for the crime, widening the hunt. This limited the hunt at Inverkeithing in 1649, when the local magistrates found their own wives accused of witchcraft.[26] There is evidence of judicial doubts about the validity of the legal process. In April 1650 as the hunt began to subside, the Chancellor, John Campbell, 1st Earl of Loudoun, writing to local commissioners about to try three Berwickshire witches, advised that they did not rely on any first confession before an ecclesiastical judge, but that they obtain a new confession before proceeding, suggesting that he thought previous prosecutions may not have been legally rigorous.[27] In the later stages of the hunt the Parliament and its representative body the Committee of Estates supervised the trials more closely, and instead of issuing commissions of judiciary to local gentlemen, it began to send Sheriff Deputes to hold special justice courts in the localities. The expense and difficulty of managing witch trials meant that local authorities often asked for help from the government, as the overwhelmed presbytery of Dunfermline did in 1649.[28] After 1650 witch trials entered a new phase, with a reduction in the total number and the abandonment of local trials in favour of mixed central-local trials.[29]

Pricking

Scottish witchcraft trials were notable for their use of pricking,[30] in which a suspect's skin was pieced with needles, pins and bodkins as it was believed that they would possess a Devil's mark through which they could not feel pain.[31] This was often undertaken by professional witch prickers, such as John Kincaid, who was active in finding marks on Patrick Watson and Manie Halieburton at Dirleton Castle before June 1649 and George Cathie, who was operating in Lanarkshire in November 1649.[32] The Newcastle trials began after the town council engaged a Scottish witch pricker, who was paid 20s for each guilty witch, but his methods raised the suspicions of the English Lieutenant-Colonel Hobson and he was eventually forced to flee.[33] According to Newcastle notable Ralph Gairdiner, he continued to operate in Northumberland, was arrested, escaped and fled to Scotland. There he was again arrested and later executed, having admitted to having caused the death through fraudulent means of 220 women accused of witchcraft in Scotland and England.[34]

Torture

Pricking could turn into a form of torture in which a subject could be repeatedly pricked until they confessed; many of the confessions gained in the 1649–50 trials were obtained in this way.[35] In 1649 the Committee of Estates passed an Act that prevented torture in cases of witchcraft, but it was probably never implemented.[36] In 1652, after the English occupation, it was reported in England that six witches had been whipped, their feet and heads burnt with lighted candles while they were strung up by their thumbs with their hands behind their backs. This, like most torture, was carried out by local clergy and magistrates without a warrant from the central courts, usually in trying to obtain an initial confession.[37] B. P. Levack argues that torture was more common in "panic years" like 1649, leading to a growth of hunts as confessions and the names of other potential witches were obtained.[38]

References

Notes

- ↑ K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The 'ill Years' of the 1690s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010) ISBN 0748638873, p. 17.

- ↑ H. O. Lancaster, Expectations of Life: A Study in the Demography, Statistics, and History of World Mortality (Springer, 1990), ISBN 038797105X, p. 381.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 221–4.

- ↑ S. MacDonald, "Creating a Godly Society: Witch-hunts, Discipline and Reformation in Scotland", Canadian Society of Church History (2010).

- 1 2 3 J. R. Young, "The Covenanters and the Scottish Parliament, 1639–51: the rule of the godly and the 'second Scottish Reformation'", E. Boran and C. Gribben, eds, Enforcing Reformation in Ireland and Scotland, 1550–1700 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0754682234, pp. 149–50.

- ↑ J. Goodare, "Witch-hunting and the Scottish state" in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, p. 138.

- ↑ S. D. M. Carpenter, Military Leadership in the British Civil Wars, 1642–1651: "the Genius of this Age" (Frank Cass, 2005), ISBN 0714655449, p. 144.

- ↑ B. P. Levack, "The decline and end of Scottish witch-hunting", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, p. 169.

- ↑ S. MacDonald, Threats to a Godly Society, the Witch-hunt in Fife, Scotland 1560–1710, D. Phil thesis, University of Guelph (1997), p. 56, n.

- ↑ B. P. Levack, Witch-hunting in Scotland: Law, Politics and Religion (London: Routledge, 2008), ISBN 0415399432, p. 56.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ MacDonald, Threats to a Godly Society, p. 82.

- ↑ S. MacDonald, Threats to a Godly Society, the Witch-hunt in Fife, Scotland 1560–1710, D. Phil thesis, University of Guelph (1997), pp. 198–199.

- ↑ S. MacDonald, "In search of the devil in Fife witchcraft cases 1560–1705", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 Levack, Witch-hunting in Scotland: Law, Politics and Religion, pp. 56 and 69.

- ↑ J. Goodare, L. Martin, J. Miller and L. Yeoman, "The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft", archived 2003, retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ↑ J. J. Megivern, The Death Penalty: An Historical and Theological Survey (Paulist Press, 1997), ISBN 0809104873, p. 192.

- ↑ M. Gaskill, Witchcraft: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), ISBN 0191613681.

- ↑ B. P. Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (London: Longman, 1987), ISBN 0-582-49123-1, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ L. Yeoman, "Hunting the rich witch in Scotland: high status witchcraft suspects and their persecutors, 1590–1650", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, p. 109.

- ↑ J. Miller, "Devices and directions: folk healing aspects of witchcraft practice in seventeenth-century Scotland", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, p. 94.

- ↑ L. Spence, The Magic Arts in Celtic Britain (1945, Courier Dover, 2012), ISBN 0486404471, p. 107.

- ↑ L. H. Willumsen, Witches of the North: Scotland and Finnmark (BRILL, 2013), ISBN 9004252924, p. 94.

- ↑ S. MacDonald, "In search of the devil in Fife witchcraft cases 1560–1705", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, pp. 41–5.

- ↑ R. Chalmers, Domestic Annals of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh and London, 1874).

- ↑ Goodare, "Witch-hunting and the Scottish state", p. 122.

- ↑ Goodare, "Witch-hunting and the Scottish state", p. 136.

- ↑ L. H. Willumsen, Witches of the North: Scotland and Finnmark (BRILL, 2013), ISBN 9004252924, p. 72.

- ↑ J. Goodare, "Witch-hunts", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 644–5.

- ↑ Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, p. 52.

- ↑ P. G. Maxwell-Stuart, Witch Hunters: Professional Prickers, Unwitchers & Witch Finders of the Renaissance (Tempus, 2005), ISBN 0752434330, pp. 148–9.

- ↑ C. L'Estrange Ewen, Witch Hunting and Witch Trials (RLE Witchcraft): The Indictments for Witchcraft from the Records of the 1373 Assizes Held from the Home Court 1559–1736 AD (1929, Routledge, 2013), ISBN 113674004X, p. 62.

- ↑ R. T. T. Davies, Four Centuries of Witch Beliefs (London: Routledge, 2012), ISBN 1136739971.

- ↑ B. P. Levack, "State building and witch hunting in early modern Europe", in J. Barry, M. Hester and G. Roberts, Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe: Studies in Culture and Belief (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), ISBN 0521638755, p. 107.

- ↑ A. Sutherland, The Brahan Seer: The Making of a Legend (Peter Lang, 2009), ISBN 3039118684, p. 66.

- ↑ Levack, "State building and witch hunting in early modern Europe", p. 106.

- ↑ B. P. Levack, "Introduction" in B. P. Levack, ed., Witchcraft, Women, and Society, Articles on Witchcraft, Magic and Demonology (Garland Publishing, 1992), ISBN 0815310323, p. 43.

Bibliography

- Cullen, K. J., Famine in Scotland: The 'ill Years' of the 1690s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010) ISBN 0748638873.

- Carpenter, S. D. M., Military Leadership in the British Civil Wars, 1642–1651: "the Genius of this Age" (Frank Cass, 2005), ISBN 0714655449.

- Chalmers, R., Domestic Annals of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh and London, 1874).

- Davies, R. T. T., Four Centuries of Witch Beliefs (London: Routledge, 2012), ISBN 1136739971.

- Gaskill, M., Witchcraft: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), ISBN 0191613681.

- Goodare, J., "Witch-hunting and the Scottish state" in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9.

- Goodare, J., "Witch-hunts", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Goodare, J., Martin, L., Miller, J. and Yeoman, L., "The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft", archived 2003, retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Lancaster, H. O., Expectations of Life: A Study in the Demography, Statistics, and History of World Mortality (Springer, 1990), ISBN 038797105X.

- L'Estrange Ewen, C., Witch Hunting and Witch Trials (RLE Witchcraft): The Indictments for Witchcraft from the Records of the 1373 Assizes Held from the Home Court 1559–1736 AD (1929, Routledge, 2013), ISBN 113674004X.

- Levack, B. P., The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (London: Longman, 1987), ISBN 0-582-49123-1.

- Levack, B. P., "Introduction" in B. P. Levack, ed., Witchcraft, Women, and Society, Articles on Witchcraft, Magic and Demonology (Garland Publishing, 1992).

- Levack, B. P., "State building and witch hunting in early modern Europe", in J. Barry, M. Hester and G. Roberts, Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe: Studies in Culture and Belief (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), ISBN 0521638755.

- Levack, B. P., "The decline and end of Scottish witch-hunting", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9.

- Levack, B. P., Witch-hunting in Scotland: Law, Politics and Religion (London: Routledge, 2008), ISBN 0415399432.

- MacDonald, S., "Creating a Godly Society: Witch-hunts, Discipline and Reformation in Scotland", Canadian Society of Church History (2010).

- MacDonald, S., Threats to a Godly Society, the Witch-hunt in Fife, Scotland 1560–1710, D. Phil thesis, University of Guelph (1997).

- MacDonald, S., "In search of the devil in Fife witchcraft cases 1560–1705", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9.

- Mackie, J. D., Lenman, B., and Parker, G., A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495.

- Maxwell-Stuart, P. G., Witch Hunters: Professional Prickers, Unwitchers & Witch Finders of the Renaissance (Tempus, 2005), ISBN 0752434330.

- Megivern, J. J., The Death Penalty: An Historical and Theological Survey (Paulist Press, 1997), ISBN 0809104873.

- Miller, J., "Devices and directions: folk healing aspects of witchcraft practice in seventeenth-century Scotland", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9.

- Mitchison, R., Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X.

- Spence, L., The Magic Arts in Celtic Britain (1945, Courier Dover, 2012), ISBN 0486404471.

- Sutherland, A., The Brahan Seer: The Making of a Legend (Peter Lang, 2009), ISBN 3039118684.

- Willumsen, L. H., Witches of the North: Scotland and Finnmark (BRILL, 2013), ISBN 9004252924.

- Wormald, J., Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3.

- Yeoman, L., "Hunting the rich witch in Scotland: high status witchcraft suspects and their persecutors, 1590–1650", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9.

- Young, J. R., "The Covenanters and the Scottish Parliament, 1639–51: the rule of the godly and the 'second Scottish Reformation'", E. Boran and C. Gribben, eds, Enforcing Reformation in Ireland and Scotland, 1550–1700 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0754682234.