Gran Paradiso National Park

| Parco nazionale del Gran Paradiso Parc national du Grand-Paradis | |

|---|---|

| |

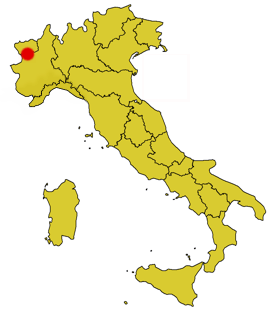

Location of park | |

| Coordinates | 45°30′10″N 7°18′36″E / 45.50278°N 7.31000°ECoordinates: 45°30′10″N 7°18′36″E / 45.50278°N 7.31000°E |

| Area | 703 km2 (271 sq mi) [1] |

| Established | 1922 |

| Governing body | Ministero dell'Ambiente |

| http://www.pngp.it | |

Gran Paradiso National Park (Italian: Parco nazionale del Gran Paradiso,[2] French: Parc national du Grand-Paradis) is an Italian national park in the Graian Alps, between the Aosta Valley and Piedmont regions.[3] The park is named after Gran Paradiso mountain, which is located in the park, and is contiguous with the French Vanoise national park. The land the park encompasses was initially protected in order to protect the Alpine ibex from poachers, as it was a personal hunting ground for king Victor Emmanuel II, but now also protects other species.[4]

History

In the early 19th century, due to hunting, the Alpine ibex only survived in the Gran Paradiso area. Approximately 60 individual ibex survived, here.[5] Ibex were intensively hunted, partly for sport, but also because their body parts were thought to have therapeutic properties:[4] talismans were made from a small cross-shaped bone near the ibex's heart in order to protect against violent death.[3] Due to the alarming decrease in the ibex population, Victor Emmanuel, soon to be King of Italy, declared the Royal Hunting Reserve of the Gran Paradiso in 1856. A protective guard was created for the ibex. Paths laid out for the ibex are still used today as part of 724 kilometres (450 mi) of marked trails and mule tracks.[4]

In 1920 Victor Emmanuel II's grandson King Victor Emmanuel III donated the park's original 21 square kilometres (5,189 acres),[4] and the park was established in 1922.[2] It was Italy's first national park.[6] There were approximately 4,000 ibex in the park when it was protected.[7] Despite the presence of the park, ibex were poached until 1945, when only 419 remained. Their protection increased, and there are now almost 4,000 in the park.[4]

Geography

The park is located in the Graian Alps in the regions of Piedmont and Aosta Valley in north-west Italy.[2][3] It encompasses 703 square kilometres (173,715 acres) of alpine terrain.[4] 10% of the park's surface area is wooded. 16.5% is used for agriculture and pasture, 24% is uncultivated, and 40% is classified as sterile. 9.5% of the park's surface area is occupied by 57 glaciers.[3] The park's mountains and valleys were sculpted by glaciers and streams.[8] Altitudes in the park range from 800-4,061 metres (2,624-13,323 ft), with an average altitude of 2,000 metres (6,561 ft).[2] Valley floors in the park are forested. There are alpine meadows at higher altitudes. There are rocks and glaciers at altitudes higher than the meadows.[8] Gran Paradiso is the only mountain entirely within the boundaries of Italy that is over 4,000 metres (13,123 ft) high.[9] Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn can be seen from its summit.[9] In 1860, John Cowell became the first person to reach the summit.[10] To the west, the park shares a boundary with France's Vanoise National Park.[2] Combined, the two parks form the largest protected area in Western Europe.[4] They co-operate in managing the ibex population, which moves across their shared boundary seasonally.[11]

Flora

The park's woods are important because they provide shelter for a large number of animals. They are a natural defence against landslides, avalanches, and flooding. The two main types of woods found in the park are coniferous and deciduous woods.[12] The deciduous European beech forests are common on the Piedmont side of the park, and are not found on the dryer Valle d'Aosta side. These forests are thick with dense foliage that lets in very little light during the summer. The beech leaves take a long time to decompose, and they form a thick layer on the woodland floor that impedes the development of other plants and trees.[12] Larches are the most common trees in the forests on the valley floors. They are mixed with spruces, Swiss stone pines, and more rarely silver firs.[8]

Maple and lime forests are found in gulleys. These forests are only present in isolated areas and are at risk of extinction. Downy oak woods are more common in the Aosta Valley area than in the Piedmont area because of its higher temperatures and lower precipitation. Oak is not a typical species in the park and it is often found mixed with Scots pine. The park's chestnut groves have been affected by human cultivation for wood and fruit. It rarely grows above 1,000 metres (3,280 ft), and the most important chestnut forests are in the park's Piedmontese side. The park's conifer woods include Scots pine groves, spruce forests dominated by the Norway spruce, often mixed with larch. Larch and Swiss stone pine woods are found up to the highest sub-alpine level (2200–2300 metres (7,217-7,546 ft)).[12]

At higher altitudes the trees gradually thin out and there are alpine pastures. These pastures are rich in flowers in the late spring.[8] The wildflowers in the park's high meadows include wild pansies, gentians, martagon lilies, and alpenroses. The park has many rocky habitats. They are mostly located above the timberline and alpine pastures. These areas have rock and detritus on their surface. Alpine plants have adapted to these habitats by assuming characteristics like dwarfism, hairiness, bright coloured flowers, and highly developed roots.[13] About 1,500 plant species can be seen at Paradisia Botanical Garden near Cogne inside the park.[4]

Fauna

Alpine ibex graze in the abundant mountain pastures in summer, and descend to lower elevations in winter.[4] Gran Paradiso's pairing with Vanoise National Park provides year-round protection to the ibex.[14] Along with the ibex, the animal species found in the park include ermine, weasel, hare,[10] Eurasian badger, alpine chamois, wolf (recently arrived from Central Italy) and maybe even lynx.[4] The ibex and chamois spend most of the year above the tree line. They descend to the valleys in the winter and spring. Alpine marmot forage on plants along the snow line.[4]

There are more than 100 bird species in the park, including Eurasian eagle-owl, rock ptarmigan, alpine accentor, and chough. Golden eagles nest on rocky ledges, and sometimes in trees. Wallcreeper are found on steep cliffs. There are black woodpeckers and nutcrackers in the park's woodlands.[4]

The park supports many species of butterflies including apollos, peak whites, and southern white admirals.[4]

References

- ↑ "Gran Paradiso National Park". World Database on Protected Areas. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Parco Nazionale del Gran Paradiso". Protected Areas and World Heritage Programme. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Price, Gillian (1997). Walking in Italy's Gran Paradiso. Cicerone Press Limited. pp. 13–16. ISBN 1-85284-231-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Riley, Laura; William Riley (2005). Nature's Strongholds: The World's Great Wildlife Reserves. Princeton University Press. pp. 390–392. ISBN 0-691-12219-9.

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. JHU Press. p. 1224. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- ↑ Mose, Ingo (2007). Protected Areas and Regional Development in Europe. p. 132. ISBN 0-7546-4801-X.

- ↑ Akitt, James Wells (1997). The Gran Paradiso and Southern Valdotain: The Long Distance Walks. Cicerone Press Limited. p. 51. ISBN 1-85284-247-4.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Parc environments". Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- 1 2 Beaumont, Peter (2005-01-30). "Have skis, will travel". The Observer. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- 1 2 Gilpin, Alan (2000). Dictionary of Environmental Law. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 208. ISBN 1-84064-188-6.

- ↑ Sandwith, Trevor (2001). Transboundary Protected Areas for Peace and Co-operation. The World Conservation Union. p. 66. ISBN 2-8317-0612-2.

- 1 2 3 "The woods". Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ↑ "The rocky environments". Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ↑ Kiss, Alexandre Charles; Dinah Shelton (1997). Manual of European Environmental Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-521-59122-8.

External links