Giuseppe Castiglione (Jesuit painter)

| Brother Giuseppe Castiglione | |

|---|---|

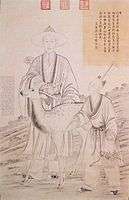

Linear perspective painting by Castiglione. (The Old Summer Palace museum collection) | |

| Born |

19 July 1688 Milan, Italy |

| Died |

17 July 1766 (aged 77) Beijing, China |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting and architecture |

Giuseppe Castiglione, S.J. (simplified Chinese: 郎世宁; traditional Chinese: 郎世寧; pinyin: Lángshìníng) (19 July 1688 – 17 July 17 1766), was an Italian Jesuit lay brother and a missionary in China, where he served as an artist at the imperial court of three emperors – the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors. He painted in a style that is a fusion of European and Chinese traditions.

Early life

Castiglione was born in Milan's San Marcellino district on 19 July 1688.[1] He was educated at home with a private tutor, then a common practice among wealthy families. He also learned to paint under the guidance of a master. In 1707, he entered the Society of Jesus in Genoa aged 19.[1] Although a Jesuit, he was never a priest. Rather, he was a lay brother.

Works

Paintings

In the late 17th century, a number of European Jesuit painters served in the Qing court of the Kangxi Emperor who was interested in employing European Jesuits trained in various fields, including painting. In the early 18th century, the Jesuits in China made a request for a painter to be sent to the imperial court in Beijing. Castiglione was identified as a promising candidate and he accepted the post.[2] In 1710 on the way to Lisbon he passed through Coimbra where he stayed for several years to decorate the chapel of St. Francis Borgia in the Church of the novitiate, today the New Cathedral of Coimbra. He painted several panels in the chapel and a Circumcision of Jesus for the main altar of the same church.[3]

In August 1715, Castiglione arrived in Macau, China, and reached Beijing later in the year.[1] He stayed at a Jesuit church called St Joseph Mission or Eastern Hall (Dong Tang) in Chinese.[4] He was presented to the Kangxi Emperor who viewed his painting of a dog, another source said a bird was also painted on the spot on Kangxi's request.[2] He was assigned a few disciples, however he initially placed to work as an artisan in the palace enameling workshop.[5]

While in China, Castiglione took the name Lang Shining (郎世寧). Castiglione adapted his Western painting style to Chinese themes and taste. His earliest surviving painting created in such style was from the first year of Yongzheng's reign in 1723.[4] He was permitted to leave the enamel workshop by Yongzheng as it was affecting his eyesight.[2] Although Castaglione was favoured by Yongzheng who commissioned a number of works by him, Yongzheng's reign was a difficult period for Jesuits as Christianity was suppressed and those missionaries not working for the emperor were expelled.[6]

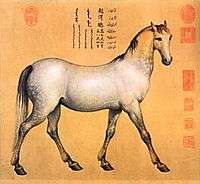

His skill as an artist was appreciated by the Qianlong Emperor, and Castiglione served the Emperor for three decades and was granted increasingly higher official rank within the Qing court.[1] He spent many years in the court painting various subjects, including the portraits of the emperor and empress. Qianlong showed particularly interest in paintings of tribute horses presented to Emperor on which Castiglione painted a series.[6]

In 1765, Castiglione and other Jesuit painters also created a series of "Battle Copper Prints" commissioned by the Emperor to commemorate his military campaigns. Small-scale copies of his paintings were shipped to Paris and rendered into engravings with etching before being returned to China. A series of sixteen prints by Castiglione (who contributed two) and his contemporaries Jean-Denis Attiret, Ignatius Sichelbart and Jean-Damascène Sallusti were created in this way.[7]

Castiglione died in Beijing in 17 July 1766.

Architecture

In addition to his skill as a painter, he was also in charge of designing the Western-Style Palaces in the imperial gardens of the Old Summer Palace. The project was initiated by Qianlong in 1747 in a garden once used by Yongzheng, with the construction of European styled palaces and gardens, aviaries, a maze, and perspective paintings organized as an outdoor theatrical stage, as well as fountains and waterworks designed by Michel Benoist. Castiglione also created trompe-l'œil paintings on the walls of the palaces.[2] The buildings however were destroyed in 1860 during the Second Opium War.[2]

Style and techniques

Castiglione's style was a unique blend of European and Chinese compositional sensibility, technique and themes. Western style was adjusted to suit Chinese taste; for example, strong shadows used in chiaroscuro techniques were unacceptable in portraiture as the Qianlong Emperor thought that shadows looked like dirt, therefore when Castiglione painted the Emperor, the intensity of the light was reduced so that there was no shadow on the face, and the features were distinct.[8] Emperors also preferred to have their portraits painted full face with a frontal posture, the royal portraits are therefore usually painted in such a manner.[9]

The paintings were done on silk, and unlike Western painting where mistake can be reworked, brushwork on silk is almost impossible to be removed, therefore requires careful and precise painting. The painting needed to be worked out in detail beforehand, which Castiglione did in a preparatory drawing on paper before he traced the design onto silk.[5] An example is the most important early work by Castiglione, One Hundred Horses in a Landscape (百駿圖), for which the preparatory drawings survive.[10] It was painted in 1728 for the Yongzheng emperor. Some of the horses are in a 'flying gallop' pose, which had not been done before by European painters.[6] The painting was executed using tempera on silk in the form of a Chinese handscroll of nearly eight meters in length. It was largely done in a European-style in accordance with the rules of perspective, and with a consistent light source. However, the dramatic chiaroscuro shading typical of Baroque paintings is reduced and there are only traces of shadow under the hooves of the horses.[5]

Castiglione was assisted in his paintings by a number of court painters. For example, in the painting Deer Hunting Patrol (哨鹿圖, Shaolutu), he would be responsible for painting the portraits of the emperor and other officials on horseback. Other members of the hunting party, the trees and landscape however would be painted by other court painters in a Chinese style that is distinctly different from Castiglione's.[1]

Legacy

Due to Castiglione's work Qing court paintings began to show a clear Western influence. Other European painters followed and a new school of painting was created that combined Chinese and Western methods. The influence of Western art on the Qing court paintings is particularly evident in the light, shade, perspective, as well as the priority given to recording contemporary events.[8]

In 2005, Castiglione became the subject of the television series Palace Artist in China, played by famed Canadian-Chinese actor Dashan (Mark Rowswell), and broadcast by China Central Television (CCTV).

Gallery

The Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor Another image of Qianlong Emperor

Another image of Qianlong Emperor The Qianlong Emperor chasing a deer on a hunting trip

The Qianlong Emperor chasing a deer on a hunting trip The Pine, Hawk and Glossy Ganoderma, painted in honour of Yongzheng's birthday, 1724[11]

The Pine, Hawk and Glossy Ganoderma, painted in honour of Yongzheng's birthday, 1724[11] Qianlong collecting lingzhi

Qianlong collecting lingzhi One of a series in Ten Prized Dogs

One of a series in Ten Prized Dogs One of Giuseppe Castiglione's Afghan Four Steeds, features a horse named Chaoni'er (超洱骢, literally Exceeding Piebald).

One of Giuseppe Castiglione's Afghan Four Steeds, features a horse named Chaoni'er (超洱骢, literally Exceeding Piebald). Ayusi assailing the rebels with a lance

Ayusi assailing the rebels with a lance Followers in the Vase

Followers in the Vase

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Musillo, Marco (2008). "Reconciling Two Careers: the Jesuit Memoir of Giuseppe Castiglione Lay Brother and Qing Imperial Painter". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 42 (no. 1): 45–59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marco Musillo (2011). "Mid-Qing Arts and Jesuit Visions: Encounters and Exchanges in Eighteenth-Century Beijing". In Susan Delson. Ai Weiwei: Circle of Animals. Prestel Publishing. pp. 146–161.

- ↑ "Colégio do Santíssimo Nome de Jesus / Igreja das Onze Mil Virgens / Catedral de Coimbra / Sé Nova de Coimbra / Igreja Paroquial da Sé Nova / Igreja do Santíssimo Nome de Jesus / Museus da Universidade de Coimbra". Património Cultural - Ministério da Cultura.

- 1 2 Hui Zou (30 April 2011). A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture. Purdue University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1557535832.

- 1 2 3 "Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766)". Media Center for Art History, University of Columbia.

- 1 2 3 Lauren Arnold (April 2003). "Of the Mind and the Eye: Jesuit Artists in the Forbidden City in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries" (PDF). Pacific Rim Report. 27.

- ↑ Castiglione, Giuseppe; Le Bas, Jacques-Philippe (1765). "Storming the Encampment at Gadan-Ola". World Digital Library (in French). Xinjiang, China. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- 1 2 Yang Xin; Rihard M. Barnhart; Nie Chongzheng; James Cahill; Lang Shaojun; Wu Hung. Three Thousand Years of Chinese Paintings. Yale University Press. pp. 282–285. ISBN 978-0-300-07013-2.

- ↑ Hui Zou (30 April 2011). A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture. Purdue University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1557535832.

- ↑ "One Hundred Horses". The Met.

- ↑ Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner's Art through the Ages: Backpack Edition, Book F: Non-Western Art Since 1300. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 1060. ISBN 978-1285838151.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giuseppe Castiglione. |

- Lang Shining and his Painting Gallery at China Online Museum

- National Palace Museum Taiwan

- Palace Artist on Mark Rowswell's website

Bibliography

- Robert Loehr, Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766) pittore di corte di Ch’ien-Lun, imperatore della Cina (Rome: ISMEO, 1940).

- George Robert Loehr, “European Artists at the Chinese Court,” in The Westward Influence of the Chinese Arts from the 14th to the 18th Century, ed. William Watson, Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia, no. 3 (London: Percival David Foundation, 1972): 333–42.

- Joseph Deheregne, Répertoire des Jésuites de Chine de 1552 à 1800 (Rome: Institutum Historicum S. I., 1973), 95.

- Willard Peterson, “Learning from Heaven: the introduction of Christianity and other Western ideas into late Ming China,” in The Cambridge History of China, ed. Denis Twitchett and Frederick W. Mote, 15 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988), 8:789–839.

- Cécile Beurdeley and Michel Beurdeley, Giuseppe Castiglione: A Jesuit Painter at the Court of the Chinese Emperors (London: Lund Humphrey, 1972).

- Hongxing Zhang, ed., The Qianlong Emperor: Treasures from the Forbidden City (Edinburgh: NMS, 2002).

- Evelyn Rawski and Jessica Rawson, China: The Three Emperors 1662–1795 (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2005).

- John W. O’Malley et al., eds., The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts 1540–1773, (Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 1999).

- Ho Wai-kam, ed., Eight Dynasties of Chinese Painting: The Collections of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, and the Cleveland Museum of Art (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1980), 355.

- Memoria Postuma Fratris Josephi Castiglione, Bras. 28, ff. 92r–93v, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Rome.

- Georg Pray, ed., Imposturae CCXVIII. in dissertatione R. P. Benedicto Cetto, Clerici Regularis e Scholis Piis de Sinensium Importuris Detectae et convulsae. Accedunt Epistolae Anecdotae R. P. Augustini e Comitibus Hallerstain ex China scriptae (Buda: Typis Regiae Universitatis, 1791).

- Marco Musillo, “La famille de Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766)”, (Paris: Thalia Edition, 2007).

- Marco Musillo, “Les peintures génoises de Giuseppe Castiglione”, (Paris: Thalia Edition, 2007).

- Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, Giuseppe Castiglione 1688-1766: Peintre et architecte à la cour de Chine (Paris: Thalia Edition, 2007), 18–25.

- Marco Musillo, “Bridging Europe and China: The Professional Life of Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766)” tesi di dottorato (University of East Anglia, 2006).

- Marco Musillo: "Reconciling two careers: the Jesuit Memoir of Giuseppe Castiglione lay brother and Qing imperial painter" in Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 42, no. 1 (2008) Pp. 45–59.

- Antonio Franco, Synopsis Annalium Societatis Jesu in Lusitania ab anno 1540 usque ad annum 1725 (Lisbon: Real collegio das artes da Companhia de Jesus, 1760), 441; e Imagem da Virtude em o Noviciado da Companhia de Jesus do Real Collegio do Espirito Santo de Evora (Lisbon: Real collegio das artes da Companhia de Jesus, 1714), 57.

- Relazione scritta da Monsignor Vescovo di Pechino al P. Giuseppe Cerù, in ordine alla Publicazione de Decreti apostolici (1715), ms. 1630, ff. 146r–152v, f. 149r. Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome.

- Copie manoscritte di vari scritti del Servo di Dio Matteo Ripa (1874), Cina e Regni Adiacenti Miscellanea 16, f. 21r, 26 December 1715, APF, Roma.

- Yang Boda, “The Development of the Ch’ien-lung Painting Academy,” in Words and Images, ed. Alfreda Murck and Wen C.Fong (New York: Princeton Univ. Press, 1991), 333–56, 345.

- George Robert Loehr, “Giuseppe Castiglione,” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1970), 22:92–94, 93.

- Father Jean Sylvain de Neu-vialle (Newielhe, 1696–1764) Relaçao da jornada, que fez ao Imperio da China, e sumamria noticia da embaixada, que deo na Corte de Pekim Em o primeiro de Mayo de 1753, o Senhor Francisco Xavier Assiz Pacheco e Sampayo (Lisbon: Officina dos Herd. De Antonio Pedrozo Galram, 1754), 8.

- Edward J. Malatesta and Gao Zhiyu, eds., Departed, yet Present. Zhalan the Oldest Christian Cemetery in Beijing (Macau and San Francisco: Instituto Cultural de Macau and Ricci Institute, 1995), 217.

- Lo-shu Fu, A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western Relations (1644–1820), 2 vols. (Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press, 1966), 1:188–89.

- Ishida Mikinosuke, “A Biographical Study of Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shih ning) a Jesuit Painter in the Court of Peking under the Ch’ing Dynasty,” Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko, no. 19 (1960): 79–121, 88–90.

Lang Shining xiaozhuan (Short biography of Lang Shining) in "Gugong bowuyuan yuankan", n. 2, 1988, pp. 3–26, 91-95.

- Aimé -Martin, M. L. (ed.) Lettres édifiantes et curieuses concernant l'Asie, l'Afrique et l'Amérique, avec quelques relations nouvelles des missions, et des notes géographiques et historiques, Paris 1838-1843, vol. II,III,IV.

- Beurdeley, C. et M., Castiglione, peintre jesuite a la cour de Chine, Fribourg 1971.

- Chayet, A., Une description tibétaine de Yuanmingyuan, in Le "Yuanmingyuan". Jeux d'eau et palais européens du XVIIIe siecle a la cour de Chine, Paris 1987.

- Cheng, T. K., Chinese Nature Painting, in "Renditions", n. 9, spring 1978, pp. 5–29.

- Durand, A., Restitution des palais européens du Yuanmingyuan, in "Arts Asiatiques", vol. XLIII, 1988, pp. 123–133.

- Hou Jinlang- Pirazzoli, M., Les chasses d'automne de l'empereur Qianlong à Mulan, in "T'oung Pao", vol. LXV, 1-3, pp. 13–50.

- Hucker, C., A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China, Stanford 1985.

- Jonathan, P.-Durant, A., La promenade occidentale de l'empereur Qianlong, in Le "Yuanmingyuan". Jeux d'eau et palais européens du XVIIIe siecle a la cour de Chine, Paris 1987, pp. 19–33.

- Ju Deyuan-Tian Jieyi-Ding Qiong, Qing gongtong huajia Lang Shining, in "Gugong bowuyuan yuankan", n. 2, 1988, pp. 27–28.

- Kao Mayching, M., China's Response to the West Art: 1898-1937, Ann Arbor, Mich. 1972.

- Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, écrites des Missions Etrangères, Nouvelle edition, Paris 1781, vol. XXII, XXIII, XXIV.

- Liu Pinsan, Huama he Lang Shining "Bajuntu" in "Gugong bowuyuan yuankan", n. 2, 1988, pp. 88–90.

- Nie Chongzheng, Lang Shining, Beijing 1984.