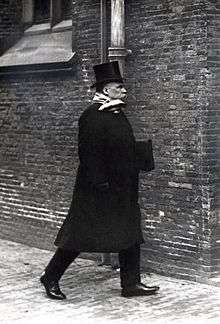

Gerard Bolland

(Leiden University)

Gerardus Johannes Petrus Josephus Bolland (9 June 1854, Groningen – 11 February 1922, Leiden), also known as G.J.P.J. Bolland, was a Dutch autodidact (self-taught man), linguist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and lecturer. An excellent orator, he gave extremely well attended public lectures in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Utrecht, Delft, Groningen, Nijmegen and Belgium.

He became an expert in German idealism, being especially interested in the works of Eduard von Hartmann and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. He began researching the formation of Christianity in 1891, and was extremely literate in religious history. He was associated with the Dutch radical school.

He effected a revival in Hegelianism in the Netherlands around 1900 by arranging a new edition of Hegel’s works, and stimulating a renewal of interest in philosophy in the Netherlands. He had a quirky style in his use of the Dutch language causing linguist J.A. Dèr Mouw, among others, to criticise him sharply.

Life

Bolland was born into a simple Catholic family in Groningen. He reached the position of professor of philosophy at the University of Leiden in 1896 after a career as a teacher in Katwijk aan Zee and as a teacher of English and German in Batavia (Dutch East-Indies).

He published "Hegel: An Historical Investigation" ("Hegel. Eene Historische Studie") in 1898, and a year later he started publishing Hegel’s most important works. In 1904 he published "Pure Reason. A book for the Friends of Wisdom" ("Zuivere Rede. Een boek voor vrienden der wijsheid").

Bolland had a "charismatic and eccentric personality, (was) harshly critical to various social groups and institutions, thus making lots of decided enemies, but also adorers.[1]". An antidemocratic conservative, he harboured a virulent hatred of Jews, Freemasons and the working class. His statue was removed from the House of Representatives in 2003 because of a complaint by MP Van Raak about Bolland's anti-Semitism.[2] Bolland described himself as “mystic and a “desperate sceptical agnostic”. Although critical of Christianity and clericalism he was a religious man. After his death, Hegelians of the right formed the Bolland Association (Bolland Genootschap).

- "The unique position of Bolland in Dutch intellectual history was a paradox in that it was a climax and a fiasco at one and the same time.[3]"

Bolland’s theory of early Christianity

Bolland continued Bruno Bauer's "concepts about Philo, the Caesars, and their influence[4]" on the development of Christianity. He believed that the basis for Christianity developed among strongly syncretised, Hellenized Jews in Alexandria and Judeophile Greeks in the early Common Era. These early beliefs revolved around a mythical Chrestos figure, and were not connected to a nationalistic Messiah figure. Among the influences in these circles were Gnosticism and Hermeticism. Philo’s writings were also a step in this development, especially the concept of the Logos.

He believed the development of Christianity took place during the first century in the decades after the Second Temple’s fall when the mythic Chrestos figure became transformed into the legendary Jesus. Bolland states that the transformed Chrestos received the name of Moses’ successor, Joshua the son of Nun, who became "leader of the people of Israel, as Moses failed to complete the task to guide the people into the promised land".[4]

According to Bolland, the Gospel of Matthew is the oldest, followed by Luke’s and then Mark’s.

References

- ↑ Klaus Schilling's translation and summary of Hermann Detering's overview of Gerardus Bolland

- ↑ Trouw, "Wijsgeer Bolland weg", September 3rd 2003, http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/4324/Nieuws/article/detail/1774615/2003/09/03/Wijsgeer-Bolland-weg.dhtml

- ↑ Harco Rutgers, "Dutch Hegelianism: The Cement Of Social Life", Section 3: Bolland: the 'self made philosopher', Rotterdam, 1994

- 1 2 Arthur Drews, Dutch Radicalism section of "The Denial of the Historicity of Jesus in Past and Present", Karlsruhe, 1926

External links

- Klaus Schilling's translation and summary of Hermann Detering's overview of Gerardus Bolland

- Klaus Schilling's summary and translation of Gerardus Bolland's "De Evangelische Jozua" ("The Gospel Jesus") from 1907

- Koninklijke bibliotheek over G.J.P.J. Bolland (Dutch language)

- Biografisch Woordenboek van Nederland Over G.J.P.J. Bolland (Dutch language)

- DBNL Archief over G.J.P.J. Bolland (Dutch language)

- Siebethissen net over het Nederlands Hegelianisme (Dutch language)