George Edwin Taylor

| George Edwin Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 4, 1857 Little Rock, Arkansas, United States |

| Died |

December 23, 1925 (aged 68) United States |

| Occupation | Newspaper editor, journalist |

| Parent(s) |

Amanda Hines Nathan Taylor |

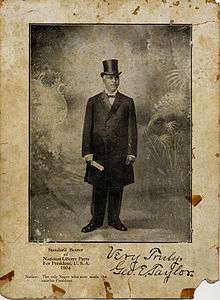

George Edwin Taylor (August 4, 1857 – December 23, 1925) was a Black American who was the candidate of the National Negro Liberty Party for the office of President of the United States in 1904.[1]

Taylor was born in Little Rock, Arkansas to Amanda Hines and Nathan Taylor (a slave). When the State of Arkansas passed the Free Negro Expulsion Act in 1859, Hines took infant George to Alton, Illinois. Hines died of Tuberculosis in 1861 or 1862. In 1865, at age 8, orphaned George arrived in La Crosse, Wisconsin where he attended school and obtained early experiences as a journalist and labor/political activist. In 1891 Taylor left Wisconsin for Oskaloosa, Iowa where he published a weekly newspaper, the Negro Solicitor. In the 1890s, Taylor transitioned from Independent Republican to Democrat. In 1892, he was founder and president of the National Colored Men’s Protection League and in 1900 was president of the National Negro Democratic League, the Negro Bureau within the National Democratic Party. In 1904, Taylor joined the National Negro Liberty Party as its candidate for the office of president of the United States. He reconnected with the Democratic Party after the failure of his 1904 election campaign. Taylor married three times: Mary Hall of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; Cora Cooper Buckner of Oskaloosa, Iowa; and Marion Tillinghast of Green Cove Springs, Florida. He owned/edited two newspapers (Wisconsin Labor Advocate of La Crosse, Wisconsin and Negro Solicitor of Oskaloosa and Ottumwa, Iowa) and was editor of the Black Star edition of Florida Times-Union of Jacksonville, Florida, the largest newspaper in Florida at the beginning of the twentieth century. Taylor was a Mason, a community organizer, and a supporter of Free Silver and Anti-Imperialism. He was a popular and humorous speaker. He died in Jacksonville, Florida. The only known biography of Taylor is For Labor, Race, and Liberty: George Edwin Taylor, his historic run for the White House, and the making of Independent Black Politics, by Bruce L. Mouser (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012).

Early life

George Edwin Taylor was born the free Black son of Amanda Hines, a free Black, and Nathan Taylor, a slave, in Little Rock, Arkansas on August 4, 1857. The precise statuses of Hines and Taylor are unknown. In 1859, Arkansas enacted a Free Negro Expulsion Bill which required all free Blacks to leave the state or be seized, and, if they refused to leave after one year, be sold as slaves.[2] Amanda Hines took infant George to Alton, Illinois, which was an antebellum center of the Underground Railroad[3] on the Mississippi River and a major river port for the Union military once the Civil War began in 1861. Hines died from Tuberculosis in 1861 or 1862. George later claimed that he, an orphan, lived in storehouse boxes in Alton during the war years.[4]

A month after the war ended in 1865, at age 8, George landed at the docks of La Crosse, Wisconsin on board the Hawkeye State, a steam side-paddle wheeler that operated between St. Paul, Minnesota and St. Louis, Missouri. Taylor remained in La Crosse for two or three years. During those years he was known as George Southall and likely lived with the family of Henry Southall,[5] a Black cook who worked on paddle wheelers. In 1867 or 1868, the Southalls moved from La Crosse, and George, at age 10 or 11, remained in La Crosse. A La Crosse County court judge intervened and fostered him to a Black family, Nathan Smith and his wife Sarah, who provided care for some of the county’s orphaned or abandoned children and who lived near West Salem, Wisconsin, twelve kilometers east of La Crosse. Taylor remained fostered to Smith until he reached the age of 20.[6] During this period, George took the name of George Edward Taylor. He attended a country school near his home.

At age 20, Taylor enrolled at Wayland University in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, where he remained for two years (1877–1879). He studied a classical curriculum that emphasized grammar, language, and rhetoric. Taylor left Wayland before completing his three-year curriculum for health and financial reasons.[7]

La Crosse period

Taylor returned to La Crosse in 1879 and changed his middle name from Edward to Edwin. On October 15, 1885, he married Mary Hall of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, who was mentioned only once in located records.[8] There were no known children from this marriage.

Taylor wrote articles for several of La Crosse's newspapers and for Chicago’s Inter Ocean. During this first year, he also obtained employment as city editor of the La Crosse Democrat, owned and edited by Marcus “Brick” Pomeroy who during the Civil War gained national notoriety by calling for President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Pomeroy also was an influential voice in the Greenback Party and within Wisconsin’s Union Greenback Labor Party.[9] Taylor became editor of the La Crosse Evening Star (1885–1886) and owner/editor of the Wisconsin Labor Advocate (1886-ca. 1887), both of which claimed to be the voice of the Knights of Labor, the La Crosse County Workingmen’s Party, and the Wisconsin State People’s Party (also known as the Wisconsin Union Labor Party).[10]

Taylor was politically active at the city, county, state, and national levels while living in La Crosse. As editor of the La Crosse Evening Star, Taylor supported the administration of Frank “White Beaver” Powell who served two terms as the people’s mayor of La Crosse, first as an independent (with no party affiliation) and then as the champion of the city’s Workingmen’s Party.[11] Taylor was Secretary (1885–1886) of the La Crosse city’s and county’s Workingmen’s Party and one of the founders of the Wisconsin People’s Party in (1886) and its State Secretary (1886–1887). He represented the state party at the Cincinnati Conference of Union Labor (February 1887) and became an advocate of Union Labor in Wisconsin (1887). Taylor’s Wisconsin Labor Advocate was the official voice of Wisconsin’s labor party in 1887.[12]

Taylor’s rapid rise in La Crosse’s and Wisconsin’s labor movement drew attention to his race at a time when the nation was reevaluating its racial attitudes. His opponents in the labor movement increasingly reminded him that he was Black. Taylor returned their racial challenges in equal kind, and his support base within La Crosse’s predominantly white community collapsed.[13]

Iowa period

Taylor claimed that he “went West” after he left La Crosse and before he appeared in Oskaloosa, Iowa in January 1891. The record is silent concerning his activities during these missing three years. By the time he surfaced in Iowa, Taylor had fully recovered his Blackness and had connected with the Republican Party where a vast majority of Black males cast their votes. He arrived in Iowa as a community organizer and a Republican Party promoter. His focus changed from “labor” to “race” in a time when the nation was increasing focusing on the issues of race and the “Negro Problem.” In this two-decade period, Taylor owned and operated a newspaper (the Negro Solicitor) and a farm, served two terms as a local Justice of the Peace (judge), transitioned from Republican to Democrat to Independent and back to Democrat, and was a policeman. He also was the head of the Negro Bureau in the National Democratic Party (1900–1904) and the candidate of the National Negro Liberty Party for the office of president of the United States in 1904.

Taylor married Cora (née Cooper) Buckner on August 25, 1894. Cora was sixteen years younger than Taylor and brought a child to the marriage. That child was mentioned only once in the record. Cora was a typist and essayist who edited the Negro Solicitor (1893–1898) when Taylor was most active at the state and national levels.[14] There were no known children to this marriage. When Taylor moved from Oskaloosa to manage a lead mine at Coalfield, Iowa in 1900 and then to operate a farm near Hilton and Albia, Iowa after 1900, Cora refused to leave Oskaloosa and the marriage ended in divorce.[15] During this phase as a farmer, Taylor also studied law and served two terms as a “justice of the peace.”[16]

No known copies of Taylor’s Negro Solicitor survived, except for scattered articles reprinted in other newspapers or found in scrapbooks. Taylor published the Negro Solicitor as an Independent Republican paper in 1892–1893 and then as a Democrat paper in 1893–1898. Taylor revived the Negro Solicitor for four to six months when he moved to Ottumwa, Iowa in 1904. Taylor also wrote articles for the Sunday Des Moines Leader in 1898.

Taylor’s period as an Independent Republican (a Negrowump) was short-lived. Iowa’s Republican leadership envisioned Taylor as someone who could speak the language of labor and who could keep Iowa’s Black coal and lead miners loyal to the party that had liberated them from slavery. Within sixteen months of his arrival in Iowa, however, Taylor abandoned the Iowa Republican Party for an independent course that emphasized racial solidarity rather than party membership.

National politics

In 1892, Taylor was positioned to play a major role as an Independent Republican. He, along with Frederick Douglass and Charles Ferguson, carried recommendations from Black Independent Republicans to the Platform Committee of the National Republican Party. That committee rejected all of their recommendations, and Taylor, in response, published a scathing “National Appeal, addressed to the American Negro and the Friends of Human Liberty.”[17] That “Appeal” effectively ended any role that he might have hoped to play within the state or national party.

Taylor’s activities at the state level primarily focused within leagues and associations that claimed to be non-partisan. These included state leagues that affiliated with the National Afro-American League (NAAL), the National Afro-American Council (NAAC), and the National Colored Men’s Protective League (NCMPL). These leagues served as black-only forums for discussing problems peculiar to the race – ideally in a non-partisan and non-confrontational setting. They also included the Iowa Colored Congress, the Iowa Knights of Pythias, and Prince Hall Masons.

Taylor’s activities at the regional and national levels, however, tended to be intensely partisan, except for his leadership role in a dysfunctional non-partisan National Colored Men’s Protective League that he led as president from 1892 until the end of the century.[18] That league expected to compete with or complement the National Afro-American League, but it accomplished little more than meet infrequently and discuss issues of importance to the race. During this period Taylor was founder and president of the Negro Inter-State Free Silver League (1897),[19] president of the National Knights of Pythias (1899),[20] and secretary (1898–1900) and then president (1900–1904) of the National Negro Democratic League which became the officially supported Negro Bureau within the National Democratic Party.[21] He also was vice-president and then president of the Negro National Free Silver League (1896–?1898),[22] vice-president of the National Negro Anti-Expansion, Anti-Imperialist, Anti-Trust and Anti-Lynching League (1899),[23] candidate of the National Negro Liberty Party for the office of president of the United States in 1904, and vice-president of the National Negro Anti-Taft League in 1908.

1904 election

Between 1900 and 1904, Taylor was president of the National Negro Democratic League.[24] Southern Democrats were enacting laws that disfranchised most Black voters and were imposing segregation through “Jim Crow” laws. Northern Democrats seemed unwilling and/or unable to control the excesses of their Southern parties. The National Negro Democratic League was fractured by the debate over the issue of linking the nation’s currency to silver as well as to gold. By 1904, Taylor was positioned to abandon the party and bureau that he had led as president for two terms. It was not a good time to be a Black democrat. It also was a time when lynching was creeping northward and when scientific racism was gaining acceptance within the nation’s intellectual and scientific community. It was not a good time to be a Black American.

“Judge” Taylor made that change in 1904 when the executive committee of the newly formed National Negro Liberty Party asked him to become their candidate for the office of president of the United States.[25] That party had its origin in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1897 when it was known as the Ex-Slave Petitioners’ Assembly. It was one of several leagues or assemblies that had formed at the end of the century to support bills then working their way through the United States Congress to grant pensions to former slaves.[26] These leagues claimed that membership in a league was required to qualify for a pension, if and when Congress passed such a bill. In 1900, that Assembly reorganized as the National Industrial Council and in 1903 added issues of lynching, Jim Crow laws, disfranchisement, anti-imperialism and scientific racism to its agenda, broadening its appeal to Black voters in Northern and Midwestern states. In 1904 the Council moved its headquarters to Chicago, Illinois and reorganized as the National Negro Civil Liberty Party.[27]

The first national convention of that new party convened in St. Louis, Missouri in July 1904, with plans to field candidates in states that had sizeable Black populations. Its platform included planks that dealt with disfranchisement, insufficient career opportunities for Blacks in the United States military, imperialism, public ownership of railroads, “self-government” for the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.), lynching, and pensions for ex-slaves. The convention also selected “Col.” William Thomas Scott of East St. Louis, Illinois as its candidate for the office of president of the United States for the 1904 election.[28] When convention delegates had left St. Louis and when Scott was arrested and jailed for having failed to pay a fine imposed in 1901, the party’s executive committee turned to Taylor who had just stepped down as president of the National Negro Democratic League to lead the party’s ticket.[29]

Taylor’s campaign in 1904 was unsuccessful. The party’s promise to put 300 speakers on the stump to support his candidacy and its plan to field 6,000 candidates for local offices failed to materialize. No newspaper supported the party. State laws kept the party from listing candidates officially on election ballots. Taylor’s name failed to be added to any state ballot. The votes he received were not recorded in state records. William Scott, who had been the party convention’s first choice as candidate, later estimated that the party had received 65,000 votes nationwide, a number that could not be verified.[30]

After the 1904 election, Taylor briefly retreated to his farm near Hilton and Albia, Iowa and then moved to Ottumwa, Iowa for health reasons. At that time Ottumwa was known for its hot springs. He remained active within the dysfunctional National Negro Liberty Party and reconnected to the Democratic Party, supporting that party’s candidates for local offices. As a reward for that support, he was appointed to a patronage position as a policeman attached to Ottumwa’s district designated for Black residences and businesses, known regionally as the “Black belt,” “Badlands,” or “tenderloin.”[31]

In 1908, he gave a keynote address to a “Union Convention” of Black political leagues that was held in Denver, Colorado at the same time that the National Democratic Party was meeting in that city. That “Union Convention” organized a National Negro Anti-Taft League that supported the candidacy of William Jennings Bryan, Democrat from Nebraska, for the office of president of the United States. Taylor was a member of that league’s committee on resolutions.[32]

Florida phase

Taylor’s reasons for moving from Iowa and to Florida in 1910 are not clearly defined. Scattered reference to health problems throughout his life in the Midwest and his move to Ottumwa for health reasons suggest that Taylor suffered from pulmonary difficulties and that he sought out those places believed to be curative for pulmonary problems. Taylor also was a Mason and had attended a national meeting of Masons in Jacksonville, Florida in 1900 as the president of Iowa’s Prince Hall Masons.[33] His Negro Solicitor had a southern readership, and he was known among the nation’s Black journalists. Jacksonville’s Black population was large, employment opportunities were much better than in Ottumwa, and hot springs on Florida’s eastern coast were believed to be particularly helpful for persons with pulmonary problems.[34]

Taylor married Marion Tillinghast of Green Cove Spring, Florida, date unknown. Tillinghast was a school teacher.

Taylor appeared first in Tampa, Florida where he became a reporter, likely for the Florida Reporter.[35] In 1911 he moved to St. Augustine, Florida where he was manager of the Magnolia Remedy Company which distributed curative salves and potions to tourists and others from the North who migrated to Florida during the winter months for health reasons. While in St. Augustine, he wrote two political tracts, “Removing the Mask” and “Backward Steps” which were popular themes from his earlier writing when he was claiming that the Republican Party was hypocritical and was retreating from its promises.[36] In 1912, Taylor was the editor of the Daily Promoter of Jacksonville and in 1917 became the editor of the “Black Star” edition of the Florida Times-Union, the state’s largest newspaper. He also was active in Jacksonville’s Young Men’s Christian Association, was a member of the Board of Commissioners for Jacksonville’s Masonic lodges, and maintained an office in Walker National Business College, one of the nation’s largest Black technical colleges.[37]

By 1912, Taylor was well connected politically within Florida and had reconnected at the national level. Taylor was an Independent first, Democrat second, and always Black. In May 1912 he attended a state convention of progressive Republicans in Jacksonville that championed the candidacy of Theodore Roosevelt against a second term bid by William Howard Taft of Ohio. Taylor, billed as “Major George Taylor of Iowa,” supported Roosevelt.[38] When Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey won that election, however, Taylor joined a group of past-presidents of the National Negro Democrat League to march past President Wilson in his 1913 Inaugural Parade.[39]

During the war years when Jacksonville became the center of repeated outbreaks of Spanish Influenza, Taylor retreated to a farm where he raised “poultry.” When the war ended, Taylor returned to Jacksonville and became the organizer/director of an exclusive “Progressive Order of Men and Women” that was essentially an investment club and mutual insurance company. He also became the editor of the Florida Sentinel. He remained connected to Walker National Business College. He died in Jacksonville on December 23, 1925.[40]

Bibliography

- Davidson, James M. “Encountering the Ex-Slave Reparation Movement from the Grave: The National Industrial Council and National Liberty Party, 1901–1907.” The Journal of African American History 97 (2012): 13–38.

- Glasrud, Bruce A., and Cary D. Wintz, African Americans and the Presidency: The road to the White House. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Mouser, Bruce L. Black La Crosse, Wisconsin, 1850–1906: Settlers, entrepreneurs, & exodusers. La Crosse, Wisconsin: La Crosse County Historical Society, Occasional Papers Series No. 1, 2002. Murphy Library.

- Mouser, Bruce L. “George Edwin Taylor (1857–1925).” Online Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, at Encyclopediaofarkansas.net.

- Mouser, Bruce L. For Labor, Race, and Liberty: George Edwin Taylor, His Historic Run for the White House, and the making of Independent Black Politics. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

- Mouser, Bruce L. “Taylor and Smith: Benevolent Fosterage.” Past, Present & Future: The Magazine of the La Crosse County Historical Society 32, no. 1 (August 2010), 1–3.

- "Sketch of Iowa Negro Presidential Candidate,” Lincoln Evening News, September 5, 1904.

- “Sketch of George Edwin Taylor: The only colored man ever nominated for the presidency,” Voice of the Negro'', October 1904, 476–81.

References

- ↑ Weeks, Linton (December 3, 2015). "A Forgotten Presidential Candidate From 1904". NPR.

- ↑ Encyclopediaofarkansas.net

- ↑ Elijah Parish Lovejoy

- ↑ Lincoln Evening News, September 5, 1904; Voice of the Negro, October 1904.

- ↑ Mouser, Black La Crosse, 38–39, 81. Murphy Library

- ↑ Mouser, “Taylor and Smith: Benevolent Fosterage,” 1–3.

- ↑ Mouser, “George Edwin Taylor: Leaving his mark,” Greetings (July 2010), 14–19 Wayland.org

- ↑ Mouser, Black La Crosse, 39–41. More detail about Taylor’s La Crosse period is found in Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty: George Edwin Taylor, His Historic Run for the White House, and the Making of Independent Black Politics (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012).

- ↑ Frank Klement, “Brick Pomeroy: Copperhead and Curmudgeon,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 35, no. 2 (1951–52), 106–13, 156–57.

- ↑ Mouser, Black La Crosse, 131-36.

- ↑ Eric Sorg, Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief: The life of White Beaver Powell, Buffalo Bill’s blood brother (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 2002), 81.

- ↑ Mouser, Black La Crosse, 131-36.

- ↑ Wisconsin Labor Advocate (available online), July 2, 1887, p.4.

- ↑ Article written by Cora Taylor

- ↑ Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty, 102.

- ↑ Oskaloosa (Iowa) Herald, July 28, 1904, p.7.

- ↑ Murphy Library

- ↑ Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening News, September 5, 1904.

- ↑ Quincy (Illinois) Daily Journal, August 18, 1897, p.5.

- ↑ Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Evening Journal, May 21, 1900, p.6.

- ↑ Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty, 102–103.

- ↑ Quincy Daily Journal, July 27, 1896, p.5, and August 25, 1897, p.7.

- ↑ Broad Ax (Chicago, Illinois), September 30, 1899, p.1.

- ↑ Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty, 102–106.

- ↑ Ottumwa (Iowa) Daily Courier, July 22, 1904, p.4.

- ↑ James Davidson, “Encountering the Ex-Slave Reparation Movement from the Grave: The National Industrial Council and National Liberty Party, 1901–1907,” The Journal of African American History 97 (2012), 13–38.

- ↑ Atlanta (Georgia) Constitution, July 27, 1903, p.9.

- ↑ For accounts of the convention, see St. Louis (Missouri) Palladium, July 16, 1904, p.1; Washington Bee, September 3, 1904, p.1.

- ↑ Daily Illinois State Register, July 14, 1904; St. Louis (Missouri) Republic, July 24, 1904.

- ↑ The Marshfield (Wisconsin) Times, February 19, 1905, p.3; Daily Illinois State Journal, January 29, 1905, p.1.

- ↑ Washington Post, April 12, 1907, p.1.

- ↑ Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, July 11, 1908, p.3; Denver (Colorado) Post, July 8, 1908, p.July 1 and 11, 1908, p.2.

- ↑ Iowa State Bystander, January 18, 1901, p.8.

- ↑ Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty, 140-42; James R. Crooks, Jacksonville After the Fire, 1901–1919 (Jacksonville: University of North Florida Press, 1991), passim.

- ↑ Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty, 139.

- ↑ Successful Americans of Our Day (Chicago: Successful Americans, 1912), 394.

- ↑ Marlene Sokol, “Black Journalist wrote and politicked for change,” The Florida Times-Union, February 27, 1984.

- ↑ Tampa (Florida) Tribune, May 19, 1912,

- ↑ Broad Ax, March 22, 1913, p.1.

- ↑ Mouser, For Labor, Race, and Liberty, 143-45.

External links

- Wisconsin Labor Advocate

- George Edwin Taylor at Genealogybank.com

- Murphy Library

- Murphy Library pictures