Tripura

Tripura

| ||

|---|---|---|

| State | ||

| ||

| ||

| Coordinates (Agartala): 23°50′N 91°17′E / 23.84°N 91.28°ECoordinates: 23°50′N 91°17′E / 23.84°N 91.28°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Formation | 21 Jan. 1972† | |

| Capital | Agartala | |

| Most populous city | Agartala | |

| Districts | 8 | |

| Government | ||

| • Governor | Tathagata Roy [1] | |

| • Chief Minister | Manik Sarkar[2] (CPI (M)) | |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (60 seats) | |

| • Parliamentary constituency |

Rajya Sabha 1 Lok Sabha 2 | |

| • High Court | Tripura High Court | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 10,491.69 km2 (4,050.86 sq mi) | |

| Area rank | 27th (2014) | |

| Population (2011) | ||

| • Total | 3,671,032 | |

| • Rank | 22nd (2014) | |

| • Density | 350/km2 (910/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+05:30) | |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-TR | |

| HDI |

| |

| HDI rank | 6th (2014) | |

| Literacy | 87.75 %. ( 4th ){2011}.[3] | |

| Official language | Kokborok and Bengali[4] | |

| Website | tripura.nic.in | |

| †It was elevated from the status of Union-Territories by the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act 1971 | ||

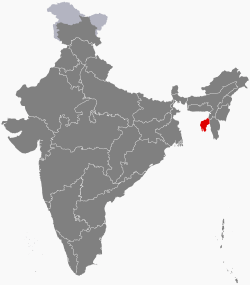

Tripura /ˈtrɪpuːrɑː/ is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers 10,491 km2 (4,051 sq mi) and is bordered by Bangladesh (East Bengal) to the north, south, and west, and the Indian states of Assam and Mizoram to the east. In 2011 the state had 3,671,032 residents, constituting 0.3% of the country's population. The Bengali Hindu people form the ethno-linguistic majority in Tripura. Indigenous communities, known in India as scheduled tribes, form about 30 per cent of Tripura's population. The Kokborok speaking Tripuri people are the major group among 19 tribes and many subtribes.

The area of modern 'Tripura' was ruled for several centuries by the Tripuri dynasty. It was the independent princely state of the Tripuri Kingdom under the protectorate of the British Empire which was known as Hill Tippera[5] while the area annexed and ruled directly by British India was known as Tippera District (present Comilla District).[6] The independent Tripuri Kingdom (or Hill Tippera) joined the newly independent India in 1949. Ethnic strife between the indigenous Tripuri people and the migrant Bengali population due to large influx of Bengali Hindu refugees and settlers from Bangladesh (former East Pakistan) led to tension and scattered violence since its integration into the country of India, but the establishment of an autonomous tribal administrative agency and other strategies have led to peace.

Tripura lies in a geographically disadvantageous location in India, as only one major highway, the National Highway 8, connects it with the rest of the country. Five mountain ranges—Boromura, Atharamura, Longtharai, Shakhan and Jampui Hills—run north to south, with intervening valleys; Agartala, the capital, is located on a plain to the west. The state has a tropical savanna climate, and receives seasonal heavy rains from the south west monsoon. Forests cover more than half of the area, in which bamboo and cane tracts are common. Tripura has the highest number of primate species found in any Indian state. Due to its geographical isolation, economic progress in the state is hindered. Poverty and unemployment continue to plague Tripura, which has a limited infrastructure. Most residents are involved in agriculture and allied activities, although the service sector is the largest contributor to the state's gross domestic product.

Mainstream Indian cultural elements, especially from Bengali culture, coexist with traditional practices of the ethnic groups, such as various dances to celebrate religious occasions, weddings and festivities; the use of locally crafted musical instruments and clothes; and the worship of regional deities. The sculptures at the archaeological sites Unakoti, Pilak and Devtamura provide historical evidence of artistic fusion between organised and tribal religions. The Ujjayanta Palace in Agartala was the former royal abode of the Tripuri king)

Name

On the face of it, the name Tripura is Sanskrit, meaning "three cities" (corresponding exactly to the Greek Tripolis). The Sanskrit name is linked to Tripura Sundari, the presiding deity of the Tripura Sundari Temple at Udaipur, one of the 51 Shakti Peethas (pilgrimage centres of Shaktism),[7][8] and to the legendary tyrant king Tripur, who reigned in the region. Tripur was the 39th descendant of Druhyu, who belonged to the lineage of Yayati, a king of the Lunar Dynasty.[9]

One of the Puranas, the text about the "exploits of Shiva", tells the story of the "sack of Tripura". (Carl Olson - 2007, "Hindu Primary Sources: A Sectarian Reader", p. 414)

However, there have been suggestions to the effect that "the origin of the name Tripura is doubtful", raising the possibility that the Sanskritic form is just due to a folk etymology of a Tibeto-Burman (Kokborok) name. Variants of the name include Tripra, Tuipura and Tippera. A Kokborok etymology from tui (water) and pra (near) has been suggested; the boundaries of Tripura extended to the Bay of Bengal when the kings of the Tripra Kingdom held sway from the Garo Hills of Meghalaya to Arakan, the present Rakhine State of Burma; so the name may reflect vicinity to the sea.[7][8][10]

History

Although there is no evidence of lower or middle Paleolithic settlements in Tripura, Upper Paleolithic tools made of fossil wood have been found in the Haora and Khowai valleys.[11] The Indian epic, the Mahabharata; ancient religious texts, the Puranas; and the Edicts of Ashoka – stone pillar inscriptions of the emperor Ashoka dating from the third century BCE – all mention Tripura.[9] An ancient name of Tripura is Kirat Desh (English: "The land of Kirat"), probably referring to the Kirata Kingdoms or the more generic term Kirata.[12]:155 However, it is unclear whether the extent of modern Tripura is coterminous with Kirat Desh.[13] The region was under the rule of the Twipra Kingdom for centuries, although when this dates from is not documented. The Rajmala, a chronicle of Tripuri kings which was first written in the 15th century,[14] provides a list of 179 kings, from antiquity up to Krishna Kishore Manikya (1830–1850),[15]:3[16][17] but the reliability of the Rajmala has been doubted.[18]

The boundaries of the kingdom changed over the centuries. At various times, the borders reached south to the jungles of the Sundarbans on the Bay of Bengal; east to Burma; and north to the boundary of the Kamarupa kingdom in Assam.[14] There were several Muslim invasions of the region from the 13th century onward,[14] which culminated in Mughal dominance of the plains of the kingdom in 1733,[14] although their rule never extended to the hill regions.[14] The Mughals had influence over the appointment of the Tripuri kings .

[14] Tripura became a princely state during British rule in India. The kings had an estate in British India, known as Tippera district or Chakla Roshnabad (now the Comilla district[6] of Bangladesh), in addition to the independent area known as Hill Tippera, the present-day state.[14] Udaipur, in the south of Tripura, was the capital of the kingdom, until the king Krishna Manikya moved the capital to Old Agartala in the 18th century. It was moved to the new city of Agartala in the 19th century. Bir Chandra Manikya (1862–1896) modelled his administration on the pattern of British India, and enacted reforms including the formation of Agartala Municipal Corporation.[19]

Following the independence of India in 1947, Tippera district – the estate in the plains of British India – became a part of East Pakistan, and Hill Tippera remained under a regency council until 1949. The Maharani Regent of Tripura signed the Tripura Merger Agreement on 9 September 1949, as a result of which Tripura became a Part C state of India.[20]:3 It became a Union Territory, without a legislature, in November 1956 and an elected ministry was installed in July 1963.[20]:3 The geographic partition that coincided with the independence of India resulted in major economic and infrastructural setbacks for the state, as road transport between the state and the major cities of India had to follow a more circuitous route. The road distance between Kolkata and Agartala before the partition was less than 350 km (220 mi), and increased to 1,700 km (1,100 mi), as the route now avoided East Pakistan.[21] The geo-political isolation was aggravated by an absence of rail transport.[22][23]:93

Some parts of the state were shelled by the Pakistan Army during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Following the war, the Indian government reorganised the North East region to ensure effective control of the international borders – three new states came into existence on 21 January 1972:[24] Meghalaya, Manipur, and Tripura.[24] Since the partition of India, many Hindu Bengalis have migrated to Tripura as refugees from East Pakistan;[20]:3–4 settlement by Hindu Bengalis increased at the time of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. Hindu Bengalis migrated to Tripura after 1949 to escape religious persecution in Muslim majority East Pakistan. Before independence, most of the population was indigenous;.[20]:9 Ethnic strife between the Tripuri tribe and the predominantly immigrant Bengali community led to scattered violence,[25] and an insurgency spanning decades. This gradually abated following the establishment of a tribal autonomous district council and the use of strategic counter-insurgency operations,[26] aided by the overall socio-economic progress of the state. Tripura remains peaceful, as of 2012.[27]

Geography

Tripura is a landlocked state in North East India, where the seven contiguous states – Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura – are collectively known as the Seven Sister States. Spread over 10,491.69 km2 (4,050.86 sq mi), Tripura is the third-smallest among the 29 states in the country, behind Goa and Sikkim. It extends from 22°56'N to 24°32'N, and 91°09'E to 92°20'E.[20]:3 Its maximum extent measures about 184 km (114 mi) from north to south, and 113 km (70 mi) east to west. Tripura is bordered by the country of Bangladesh to the west, north and south; and the Indian states of Assam to the north east; and Mizoram to the east.[20]:3 It is accessible by national highways passing through the Karimganj district of Assam and Mamit district of Mizoram.[28]

Topology

The physiography is characterised by hill ranges, valleys and plains. The state has five anticlinal ranges of hills running north to south, from Boromura in the west, through Atharamura, Longtharai and Shakhan, to the Jampui Hills in the east.[29]:4 The intervening synclines are the Agartala–Udaipur, Khowai–Teliamura, Kamalpur–Ambasa, Kailasahar–Manu and Dharmanagar–Kanchanpur valleys.[29]:4 At an altitude of 939 m (3,081 ft), Betling Shib in the Jampui range is the state's highest point.[20]:4 The small isolated hillocks interspersed throughout the state are known as tillas, and the narrow fertile alluvial valleys, mostly present in the west, are called lungas.[20]:4 A number of rivers originate in the hills of Tripura and flow into Bangladesh.[20]:4 The Khowai, Dhalai, Manu, Juri and Longai flow towards the north; the Gumti to the west; and the Muhuri and Feni to the south west.[29]:73

The lithostratigraphy data published by the Geological Survey of India dates the rocks, on the geologic time scale, between the Oligocene epoch, approximately 34 to 23 million years ago, and the Holocene epoch, which started 12,000 years ago.[29]:73–4 The hills have red laterite soil that is porous. The flood plains and narrow valleys are overlain by alluvial soil, and those in the west and south constitute most of the agricultural land.[20]:4 According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, on a scale ranging from I to V in order of increasing susceptibility to earthquakes, the state lies in seismic zone V.[30]

Climate

The state has a tropical savanna climate, designated Aw under the Köppen climate classification. The undulating topography leads to local variations, particularly in the hill ranges.[31] The four main seasons are winter, from December to February; pre-monsoon or summer, from March to April; monsoon, from May to September; and post-monsoon, from October to November.[32] During the monsoon season, the south west monsoon brings heavy rains, which cause frequent floods.[20]:4[29]:73 The average annual rainfall between 1995 and 2006 ranged from 1,979.6 to 2,745.9 mm (77.94 to 108.11 in).[33] During winter, temperatures range from 13 to 27 °C (55 to 81 °F), while in the summer they fall between 24 and 36 °C (75 and 97 °F).[32] According to a United Nations Development Programme report, the state lies in "very high damage risk" zone from wind and cyclones.[34]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

32.8 (91) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.1 (88) |

29.2 (84.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

30.52 (86.93) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10 (50) |

13.2 (55.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.2 (72) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

22 (72) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

19.66 (67.43) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 27.5 (1.083) |

21.5 (0.846) |

60.7 (2.39) |

199.7 (7.862) |

329.9 (12.988) |

393.4 (15.488) |

363.1 (14.295) |

298.7 (11.76) |

232.4 (9.15) |

162.5 (6.398) |

46 (1.81) |

10.6 (0.417) |

2,146 (84.487) |

| Source: [35] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

| State symbols of Tripura[36] | |

| State animal | Phayre's langur |

| State bird | Green imperial pigeon |

| State tree | Agar |

| State flower | Nagesar |

Green imperial pigeon the state bird of tripura Like most of the Indian subcontinent, Tripura lies within the Indomalaya ecozone. According to the Biogeographic classification of India, the state is in the "North-East" biogeographic zone.[37] In 2011 forests covered 57.73 per cent of the state.[38] Tripura hosts three different types of ecosystems: mountain, forest and freshwater.[39] The evergreen forests on the hill slopes and the sandy river banks are dominated by species such as Dipterocarpus, Artocarpus, Amoora, Elaeocarpus, Syzygium and Eugenia.[40] Two types of moist deciduous forests comprise majority of the vegetation: moist deciduous mixed forest and Sal (Shorea robusta)-predominant forest.[40] The interspersion of bamboo and cane forests with deciduous and evergreen flora is a peculiarity of Tripura's vegetation.[40] Grasslands and swamps are also present, particularly in the plains. Herbaceous plants, shrubs, and trees such as Albizia, Barringtonia, Lagerstroemia and Macaranga flourish in the swamps of Tripura. Shrubs and grasses include Schumannianthus dichotoma (shitalpati), Phragmites and Saccharum (sugarcane).[40]

According to a survey in 1989–90, Tripura hosts 90 land mammal species from 65 genera and 10 orders,[41] including such species as elephant (Elephas maximus), bear (Melursus ursinus), binturong (Arctictis binturong), wild dog (Cuon alpinus), porcupine (Artherurus assamensis), barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), sambar (Cervus unicolor), wild boar (Sus scrofa), gaur (Bos gaurus), leopard (Panthera pardus), clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa), and many species of small cats and primates.[41] Out of 15 free ranging primates of India, seven are found in Tripura; this is the highest number of primate species found in any Indian state.[41] The wild buffalo (Bubalus arnee) is extinct now.[42] There are nearly 300 species of birds in the state.[43]

Wildlife sanctuaries of the state are Sipahijola, Gumti, Rowa and Trishna wildlife sanctuaries.[44] National parks of the state are Clouded Leopard National Park and Rajbari National Park.[44] These protected areas cover a total of 566.93 km2 (218.89 sq mi).[44] Gumti is also an Important Bird Area.[45] In winter, thousands of migratory waterfowl throng Gumti and Rudrasagar lakes.[46]

Divisions

In January 2012, major changes were implemented in the administrative divisions of Tripura. Beforehand, there had been four districts – Dhalai (headquarters Ambassa), North Tripura (headquarters Kailashahar), South Tripura (headquarters Udaipur), and West Tripura (headquarters Agartala). Four new districts were carved out of the existing four in January 2012 – Khowai, Unakoti, Sipahijala and Gomati.[47] Six new subdivisions and five new blocks were also added.[48] Each is governed by a district collector or a district magistrate, usually appointed by the Indian Administrative Service. The subdivisions of each district are governed by a sub-divisional magistrate and each subdivision is further divided into blocks. The blocks consist of Panchayats (village councils) and town municipalities. As of 2012, the state had eight districts, 23 subdivisions and 45 development blocks.[49] National census and state statistical reports are not available for all the new administrative divisions, as of March 2013. Agartala, the capital of Tripura, is the most populous city. Other major towns with a population of 10,000 or more (as per 2015 census) are Sabroom, Dharmanagar, Jogendranagar, Kailashahar, Pratapgarh, Udaipur, Amarpur, Belonia, Gandhigram, Kumarghat, Khowai, Ranirbazar, Sonamura, Bishalgarh, Teliamura, Mohanpur, Melaghar, Ambassa, Kamalpur, Bishramganj, Kathaliya, Santirbazar and Baxanagar.

Government and politics

Tripura is governed through a parliamentary system of representative democracy, a feature it shares with other Indian states. Universal suffrage is granted to residents. The Tripura government has three branches: executive, legislature and judiciary. The Tripura Legislative Assembly consists of elected members and special office bearers that are elected by the members. Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker or the Deputy Speaker in case of Speaker's absence. The Assembly is unicameral with 60 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA).[50] The members are elected for a term of five years, unless the Assembly is dissolved prior to the completion of the term. The judiciary is composed of the Tripura High Court and a system of lower courts.[51][52] Executive authority is vested in the Council of Ministers headed by the Chief Minister. The Governor, the titular head of state, is appointed by the President of India. The leader of the party or a coalition of parties with a majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed as the Chief Minister by the Governor. The Council of Ministers are appointed by the Governor on the advice of the Chief Minister. The Council of Ministers reports to the Legislative Assembly.

Tripura sends two representatives to the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the parliament of India) and one representative to the Rajya Sabha (parliament's upper house). Panchayats (local self-governments) elected by local body elections are present in many villages for self-governance. Tripura also has a unique tribal self-governance body, the Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council.[53] This council is responsible for some aspects of local governance in 527 villages with high density of the scheduled tribes.[53][54]

The main political parties are the Left Front and All india trinamool congress with the Bharatiya janata party having limited support base along with regional parties like IPFT, INPT and the Indian National Congress. Until 1977, the state was governed by the Indian National Congress.[55]:255–66 The Left Front was in power from 1978 to 1988, and then again from 1993 onwards.[56] During 1988–1993, the Congress and Tripura Upajati Juba Samiti were in a ruling coalition.[57] In the last elections held in February 2013, the Left Front won 50 out of 60 seats in the Assembly, 49 of which went to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM).[58] As of 2013, Tripura is one of the two states in India where the communist party is in power. The other state is Kerala. Formerly, one more state—West Bengal—had democratically elected communist governments.[59]

Communism in the state had its beginnings in the pre-independence era, inspired by freedom struggle activities in Bengal, and culminating in regional parties with communist leanings.[60]:362 It capitalised on the tribal dissatisfaction with the mainstream rulers,[60]:362 and has been noted for connection with the "sub-national or ethnic searches for identity".[61] Since the 1990s, there is an ongoing irredentist Tripura rebellion, involving militant outfits such as the National Liberation Front of Tripura and the All Tripura Tiger Force (ATTF); terrorist incidents involving the ATTF claimed a recorded number of 389 victims in the seven-year period of 1993 to 2000.[62] The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA) was first enforced in Tripura on 16 February 1997 when terrorism was at its peak in the state. Ever since it was enforced in Tripura, the Act, as per its provisions, was reviewed and extended after every six months. However, in view of the improvement in the situation and fewer terrorist activities being reported, the Tripura government in June 2013 reduced operational areas of the AFSPA to 30 police station areas. The last six-month extension to AFSPA was given in November 2014, and after about 18 years of operation, it was repealed on 29 May 2015. tribal students Organization Twipra students Federation (TSF) demand for revoke AFSPA fro the state [63]

Economy

| Gross State Domestic Product at Constant Prices (2004–05 base)[64] figures in crores Indian rupee | |

| Year | Gross State Domestic Product |

|---|---|

| 2004–05 | 8,904 |

| 2005–06 | 9,482 |

| 2006–07 | 10,202 |

| 2007–08 | 10,988 |

| 2008–09 | 11,596 |

| 2009–10 | 12,248 |

| 2010–11 | 12,947 |

Tripura's gross state domestic product for 2010–11 was ₹129.47 billion (US$1.9 billion) at constant price (2004–05),[64] recording 5.71 per cent growth over the previous year. In the same period, the GDP of India was ₹48,778.42 billion (US$720 billion), with a growth rate of 8.55 per cent.[64] Annual per capita income at current price of the state was ₹38,493 (US$570), compared to the national per capita income ₹44,345 (US$660).[65] In 2009, the tertiary sector of the economy (service industries) was the largest contributor to the gross domestic product of the state, contributing 53.98 per cent of the state's economy compared to 23.07 per cent from the primary sector (agriculture, forestry, mining) and 22.95 per cent from the secondary sector (industrial and manufacturing).[65] According to the Economic Census of 2005, after agriculture, the maximum number of workers were engaged in retail trade (28.21 per cent of total non-agricultural workforce), followed by manufacturing (18.60 per cent), public administration (14.54 per cent), and education (14.40 per cent).[66]

Tripura is an agrarian state with more than half of the population dependent on agriculture and allied activities.[67] However, due to hilly terrain and forest cover, only 27 per cent of the land is available for cultivation.[67] Rice, the major crop of the state, is cultivated in 91 per cent of the cropped area.[67] According to the Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Government of Tripura, in 2009–10, potato, sugarcane, mesta, pulses and jute were the other major crops cultivated in the state.[68] Jackfruit and pineapple top the list of horticultural products.[68] Traditionally, most of the indigenous population practised jhum method (a type of slash-and-burn) of cultivation. The number of people dependent on jhum has declined over the years.[69]:37–9

Pisciculture has made significant advances in the state. At the end of 2009–10, the state produced a surplus of 104.3 million fish seeds.[70] Rubber and tea are the important cash crops of the state. Tripura ranks second only to Kerala in the production of natural rubber in the country.[71] The state is known for its handicraft, particularly hand-woven cotton fabric, wood carvings, and bamboo products. High quality timber including sal, garjan, teak and gamar are found abundantly in the forests of Tripura. Tata Trusts signed a pact with Government of Tripura in July, 2015 to improve fisheries and dairy in the state.[72]

| Per Capita Income with 2004–05 Base | ||

| Year | Tripura | India |

|---|---|---|

| 2004–05 | 24,394 | 24,095 |

| 2005–06 | 26,668 | 27,183 |

| 2006–07 | 29,081 | 31,080 |

| 2007–08 | 31,111 | 35,430 |

| 2008–09 | 33,350 | 40,141 |

| 2010–11 | 33,493 | 44,345 |

The industrial sector of the state continues to be highly underdeveloped – brickfields and tea industry are the only two organised sectors.[66] Tripura has considerable reservoirs of natural gas.[29]:78–81 According to estimates by Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), the state has 400 billion metres3 reserves of natural gas, with 16 billion metres3 is recoverable.[71] ONGC produced 480 million metres3 natural gas in the state, in 2006–07.[71] In 2011 and 2013, new large discoveries of natural gas were announced by ONGC.[73] Tourism industry in the state is growing – the revenue earned in tourism sector crossed ₹10 million (US$150,000) for the first time in 2009–10, and surpassed ₹15 million (US$220,000) in 2010–11.[74] Although Bangladesh is in a trade deficit with India, its export to Tripura is significantly more than import from the state; a report in the newspaper The Hindu estimated Bangladesh exported commodities valued at about ₹3.5 billion (US$52 million) to the state in 2012, as opposed to "very small quantity" of import.[75] Alongside legal international trade, unofficial and informal cross-border trade is rampant.[76] In a research paper published by the Institute of Developing Economies in 2004, the dependence of Tripura's economy on that of Bangladesh was emphasised.[77]:313

The economy of Tripura can be characterised by high rate of poverty, low capital formation, inadequate infrastructure facilities, geographical isolation and communication bottlenecks, inadequate exploration and use of forest and mineral resources, slow industrialisation and high unemployment. More than 50% of the population depends on agriculture for sustaining their livelihood.[78] However agriculture and allied activities to Gross State Domestic Production (GSDP) is only 23%, this is primarily because of low capital base in the sector. Despite the inherent limitation and constraints coupled with severe resources for investing in basic infrastructure, this has brought consistence progress in quality of life and income of people cutting across all sections of society. The state government through its Tripura Industrial Policy and Tripura Industrial Incentives Scheme, 2012, has offered heavy subsidies in capital investment and transport, preferences in government procurement, waivers in tender processes and fees, yet the impact has been not much significant beyond a few industries being set up in the Bodhjungnagar Industrial Growth Center.[79]

The Planning Commission estimates the poverty rate of all North East Indian states by using head count ratio of Assam (the largest state in North East India). According to 2001 Planning Commission assessment, 22 per cent of Tripura's rural residents were below the poverty line. However, Tripura government's independent assessment, based on consumption distribution data, reported that, in 2001, 55 per cent of the rural population was below the poverty line.[66] Geographic isolation and communication bottleneck coupled with insufficient infrastructure have restricted economic growth of the state.[67] High rate of poverty and unemployment continues to be prevalent.[67]

Infrastructure

Transport

Only one major road, the National Highway 8 (NH-8), connects Tripura to the rest of India.[80] Starting at Sabroom in southern Tripura, it heads north to the capital Agartala, turns east and then north-east to enter the state of Assam. Locally known as "Assam Road", the NH-8 is often called the lifeline of Tripura.[80] However, the highway is single lane and of poor quality; often landslides, rains or other disruptions on the highway cut the state off from its neighbours.[29]:73[69]:8 Another National Highway, NH 8A, connects the town Manu in South Tripura district with Aizawl, Mizoram.[28] The Tripura Road Transport Corporation is the government agency overlooking public transport on road. A hilly and land-locked state, Tripura is dependent mostly on roads for transport.[80] The total length of roads in the state is 16,931 km (10,520 mi) of which national highways constitute 88 km (55 mi) and state highways 689 km (428 mi), as of 2009–10.[80] Residents in rural areas frequently use waterways as a mode of transport.[81]:140

Agartala Airport, located 12.5 km (6.7 nautical miles) northwest of Agartala at Singerbhil, is the second busiest airport in north east India after Guwahati. There are direct flight connections to Kolkata, Imphal, Delhi, Silchar, Aizwal, Guwahati, Bangalore, Chennai, Ahmedabad and Mumbai. The major airlines are Air India, Jet Airways (Operating Codeshare and connect Flights), Indigo Airlines and Spicejet. Passenger helicopter services are available between the capital and major towns (Kailashahar, Dharmanagar) as well as to more remote areas such as Kanchanpur and Gandacherra.[80]

Rail transport was absent in the state until 2008–09 when a rail connection was established between the capital Agartala and Lumding junction in Assam.[80] This is a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) meter gauge rail track connecting to the usual 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) broad gauge at Lumding. The major railways stations in this line are in Agartala, Dharmanagar, and Kumarghat. As of 2009–10, the total length of railway tracks in the state is 153 kilometres (95 mi). Extension of railway line from Agartala to the southernmost town of Sabroom is in progress, as of 2012.[80]

Tripura has an 856 km (532 mi) long international border with Bangladesh, of which 730.5 km (453.9 mi) is fenced, as of 2012.[82] Several locations along the border serve as bilateral trading points between India and Bangladesh, such as Akhaura near Agartala, Raghna, Srimantpur, Belonia, Khowai and Kailasahar.[75] A bus service exists between Agartala and Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.[83][84] In 2013, the two countries signed an agreement to establish a 15 km (9.3 mi) railway link between Agartala and the Akhaura junction of Bangladesh.[85] Citizens of both countries need visa to legally enter the other country; however, illegal movement and smuggling across the border are widespread.[77]:314[86]

Media and communication

As of 2014, 56 daily and weekly newspapers are published in Tripura.[87] Most of the newspapers are published in Bengali, except for one Kokborok daily (Hachukni Kok), one Manipuri weekly (Marup), two English dailies and three bilingual weeklies.[87] Notable dailies include Ajkal Tripura, Daily Desher Katha, Dainik Sambad and Syandan Patrika.[87] and popular news portal www.tripurachronicle.in In a study by Indian Institute of Mass Communication in 2009, 93 per cent of the sampled in Tripura rated television as very effective for information and mass education.[88] In the study, 67 per cent of the sampled listened to radio and 80–90 per cent read newspaper.[88] Most of the major Indian telecommunication companies are present in the state, such as Airtel, Aircel, Vodafone, Reliance, Tata Indicom, Idea and BSNL. Mobile connections outnumber landline connections by a wide margin. As of 2011, the state-controlled BSNL has 57,897 landline subscribers and 325,279 GSM mobile service connections.[80] There are 84 telephone exchanges (for landlines) and 716 post offices in the state, as of 2011.[80]

Electricity production

Till 2014, Tripura was a power deficit state. In late 2014, Tripura reached surplus electricity production capacity by using its recently discovered natural gas resources, and installing high efficiency gas turbine power plants. The state has many power-generating stations. These are owned by Tripura State Electricity Corporation (TSECL), natural gas-powered thermal power stations at Rokhia and Baramura, and the ONGC Tripura Power Company in Palatana.[89] The ONGC plant has a capacity of 726.6 MW, with the second plant's commissioning in November 2014.[90][91] It is the largest individual power plant in the northeast region.[92]

The state also has a hydro power station on the Gumti River. The combined power generation from these three stations is 100–105 MW.[93] The North Eastern Electric Power Corporation (NEEPCO) operates the 84 MW Agartala Gas Turbine Power Plant near Agartala.[93] As of November 2014, another thermal power plant is being built at Monarchak.[94]

With the newly added power generation capacity, Tripura has with enough capacity to supply all seven sister states of northeast India, as well export power to neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh.[95] With recent discoveries, the state has abundant natural gas reserves to support many more power generation plants, but lacks pipeline and transport infrastructure to deliver the fuel or electricity to India's national grid.

Irrigation and fertilizers

As of 2011, 255,241 hectares (985 sq mi) of land in Tripura cultivable, of which 108,646 hectares (419 sq mi) has the potential to be covered by irrigation projects. However, only 74,796 hectares (289 sq mi) is irrigated.[96] The state lacks major irrigation projects; it depends on medium-sized projects sourced from Gumti, Khowai (at Chakmaghat) and Manu rivers, and minor projects administered by village-level governing bodies that utilise tube wells, water pumps, tanks and lift irrigation.[96]

ONGC and Chambal Fertilizers & Chemicals are jointly building a fertiliser plant to leverage ONGC's natural gas discoveries in Tripura.[97] Expected to be in operation by 2017, the 1.3 million tonnes per year plant will supply the northeastern states.[98]

Drinking water

Drinking Water and Sanitation (DWS) wing of Public Works Department manages the drinking water supply in the state. Schools and Anganwadi Centers have been specifically targeted to improve drinking water supply as well as attendance to these institutions. Many areas of Tripura have the problem of excessive iron content in ground water requiring installation of Iron Removal Plants (IRP). Tripura State has received the best State Award for Water & Sanitation under the category of Small States in the IBN7 Diamond State Award function for doing commendable work to provide drinking water supply to the people with sparsely distributed tribal population in hamlets of hilly region of the State. However, a study by the DWS Department found depleting water table and excessive contamination.[99] Still, packaged drinking water under brands "Tribeni", "Eco Freshh", "Blue Fina", "Life Drop" and "Aqua Zoom" among others is manufactured and sold in the state. Filters of many types and brands, in addition to locally manufactured ceramic type filters, are sold in the state although their acceptance in rural areas is less.

Sanitation

Tripura has high incidence of open defecation, especially in the interior hilly and forest areas. The state has extensively implemented Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan and currently the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and convergence with MGNREGS to address this problem. Schools and Anganwadi Center are focussed to provide with urinals and latrines, separate for boys and girls aling with baby friendly toilets in Anganwadi Centers to inculcate the habit of using sanitary latrines in young age. However many toilets lie dysfuncational due to lack of maintenance and damage. Earlier schemes of providing plastic squatting plates, free of cost to people, has not produced results as most of them lie unused as many people cannot afford to construct a toilet. Open defecation has created problems of diarrhoea and vulnerability to malaria. The Chief Minister of Tripura has envisioned to make the state Open Defecation Free (ODF) by 2017.

Education

Schools in Tripura are run by the state government elected by the people,TTAADC and private organisations, which include religious institutions. Instruction in schools is mainly in English or Bengali, though Kokborok and other regional languages are also used. Some of the special schools include Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalaya, Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya, residential schools run by Tripura Tribal Welfare Residential Educational Institutions Society (TTWREIS),[101] missionary organisations like St. Paul's, St. Arnold's, Holy Cross, Don Bosco, St. John's etc. There are also many Preschools mostly located in cities like Kidzee Agartala at 79 tilla, GB in Agartala. The schools are affiliated to the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) or the Tripura Board of Secondary Education.[102] Under the 10+2+3 plan, after completing secondary school, students typically enroll for two years in a junior college or in a higher secondary school affiliated either to the Tripura Board of Secondary Education or to other central boards. Students choose from one of the three streams—liberal arts, commerce or science.[102] As in the rest of India,[103] after passing the Higher Secondary Examination (the grade 12 examination), students may enroll in general degree programs such as bachelor's degree in arts, commerce or science, or professional degree programs such as engineering, law or medicine.

According to the Economic Review of Tripura 2010–11, Tripura has a total of 4,455 schools, of which 2,298 are primary schools.[100] The total enrolment in all schools of the state is 767,672.[100] Tripura has one Central University (Tripura University) and one private university (a branch of the Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts of India). There are 15 general colleges, three engineering colleges (Tripura Institute of Technology, National Institute of Technology, Agartala and NIEILT, Agartala), two medical colleges (Agartala Government Medical College[104] and Tripura Medical College[105]), three nursing or paramedical colleges, three polytechnic colleges, one law college, one Government Music College, one College of Fisheries, Institute of Advance Studies in Education, one Regional College of Physical Education at Panisagar and one art college.[100][106] Tripura University also houses the IGNOU Agartala Regional Center.

Healthcare

| Health indices as of 2010[107] | ||

| Indicator | Tripura | India |

|---|---|---|

| Birth rate | 14.9 | 22.1 |

| Death rate | 5.0 | 7.2 |

| Infant mortality rate | 27 | 47 |

| Total fertility rate | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| Natural growth rate | 9.9 | 14.9 |

Healthcare in Tripura features a universal health care system run by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare of the Government of Tripura.[108] The health care infrastructure is divided into three tiers – the primary health care network, a secondary care system comprising district and sub-divisional hospitals and tertiary hospitals providing speciality and super speciality care. As of 2010–11, there are 17 hospitals, 11 rural hospitals and community health centres, 79 primary health centres, 635 sub-centres/dispensaries, 7 blood banks and 7 blood storage centres in the state.[109] Homeopathic and Ayurvedic styles of medicine are also popular in the state.[109] The National Family Health Survey – 3 conducted in 2005–06 revealed that 20 per cent of the residents of Tripura do not generally use government health facilities, and prefers private medical sector.[110] This is overwhelmingly less compared to the national level, where 65.6 per cent do not rely on government facilities.[110] As in the rest of India, Tripura residents also cite poor quality of care as the most frequent reason for non-reliance over public health sector. Other reasons include distance of the public sector facility, long waiting time, and inconvenient hours of operation.[110] As of 2010, the state's performance in major public health care indices, such as birth rate, infant mortality rate and total fertility rate is better than the national average.[107] The state is vulnerable to epidemics of Malaria, Diarrhea, Japanese Encephalitis and Meningitis. In summer 2014 the state witnessed a major Malaria outbreak.[111]

Demographics

Population

| Population growth[112] | ||

| Census | Population | %± |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 639,000 | — |

| 1961 | 1,142,000 | 78.7% |

| 1971 | 1,556,000 | 36.3% |

| 1981 | 2,053,000 | 31.9% |

| 1991 | 2,757,000 | 34.3% |

| 2001 | 3,199,203 | 16% |

| 2011 | 3,671,032 | 14.7% |

Tripura ranks second only to Assam as the most populous state in North East India. According to the provisional results of 2011 census of India, Tripura has a population of 3,671,032 with 1,871,867 males and 1,799,165 females.[113] It constitutes 0.3 per cent of India's population. The sex ratio of the state is 961 females per thousand males,[113] higher than the national ratio 940. The density of population is 350 persons per square kilometre.[114] The literacy rate of Tripura in 2011 was 87.75 per cent,[113] higher than the national average 74.04 per cent, and third best among all the states.

Tripura ranked 6th in Human Development Index (HDI) among 35 states and union territories of India, according to 2006 estimate by India's Ministry of Women and Child Development; the HDI of Tripura was 0.663, better than the all-India HDI 0.605.[115]

In 2011, the police in Tripura recorded 5,803 cognisable offences under the Indian Penal Code, a number second only to Assam (66,714) in North East India.[116] The crime rate in the state was 158.1 per 100,000 people, less than the all-India average of 192.2.[117] However, 2010 reports showed that the state topped all the states for crime against women, with a rate of 46.5 per 100,000 people, significantly more than the national rate of 18.[118]

Languages

In the 2001 census of India, Bengalis represented almost 70 per cent of Tripura's population while the Tripuri population amounted to 30 per cent.[119] The state's "scheduled tribes", historically disadvantaged groups of people recognised by the country's constitution, consist of 19 ethnic groups and many sub-groups,[123] with diverse languages and cultures. In 2001, the largest such group was the Kokborok-speaking Tripuris, which had a population of 543,848, representing 17.0 per cent of the state's population and 54.7 per cent of the "scheduled tribe" population.[119] The other major groups, in descending order of population, were the Reang (16.6 per cent of the indigenous population), Jamatia (7.5 per cent), Chakma (6.5 per cent), Halam (4.8 per cent), Mog (3.1 per cent), Munda (1.2 per cent), Kuki (1.2 per cent) and Garo (1.1 per cent).[119] Bengali is the most widely spoken language. Kokborok is a prominent language among the Tripura tribes. Several other languages such as Hindi, Mog, Odia, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Manipuri, Halam, Kuki, Garo and Chakma belonging to Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan families are spoken in the state.[124] Saimar, a nearly extinct language, is spoken by only four people in one village, as of 2012.[125]

Religion

According to 2011 census, Hinduism is the majority religion in the state, followed by 81.4 per cent of the population.[127] Muslims make up 10.6 per cent of the population, Christians 4.35 per cent, and Buddhists 3.41 per cent.[127] The Muslim percentage in the state gradually declined from 1971 due to heavy influx of Hindu population from and the migration of Muslim population to Bangladesh. Mogs (Barua & Mutsuddy also comes under Mog community) and Chakmas are the followers of Buddhism in Tripura.

Christianity is chiefly followed by members of the Lushai, Kuki, Garo, Tripuri, Halam tribes and as per 2011 census has 159,882 adherents.[81]:135–6

Culture

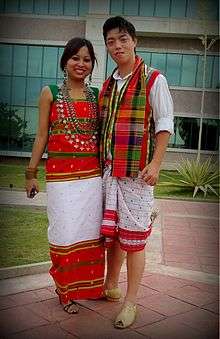

The diverse ethno-linguistic groups of Tripura have given rise to a composite culture.[128][129] The dominant ethnic groups are Bengali, Tripuri (Debbarma, Tripura, Jamatia, Reang, Noatia, Koloi, Murasing, Chakma, Halam, Garo, Kuki, Mizo, Uchoi, Dhamai, Roaza, Mogh, Manipuri, and other tribal groups such as Munda, Oraon and Santhal who migrated in Tripura as a tea labourers.[123] Bengali people represent the largest ethno-linguist community of the state. Bengali culture, as a result, is the main non-indigenous, non-Tripura culture. Indeed, many elite tribal families which reside in towns have actively embraced Bengali culture and language in the past, but in today's generation more Tripuris are embracing their culture.[130] The Tripuri kings were great patrons of Bengali culture, especially literature;[130] Bengali language was the language of the court.[131] Elements of Bengali culture, such as Bengali literature, Bengali music, and Bengali cuisine are widespread, particularly in the urban areas of the state.[130][132]:110[133]

Tripura is noted for bamboo and cane handicrafts.[129] Bamboo, wood and cane are used to create an array of furniture, utensils, hand-held fans, replicas, mats, baskets, idols and interior decoration materials.[23]:39–41[134] Music and dance are integral to the culture of the state. Some local musical instruments are the sarinda, chongpreng (both string instruments), and sumui (a type of flute).[12]:344–5 Each indigenous community has its own repertoire of songs and dances performed during weddings, religious occasions, and other festivities. The Tripuri and Jamatia people perform goria dance during the Goria puja. Jhum dance (also called tangbiti dance), lebang dance, mamita dance, and mosak sulmani dance are other Tripuri dance forms.[135] Reang community, the second largest scheduled tribe of the state, is noted for its hojagiri dance that is performed by young girls balanced on earthen pitchers.[135] Bizhu dance is performed by the Chakmas during the Bizhu festival (the last day of the month of Chaitra in Hindu calendar). Other dance forms include wangala dance of the Garo people, hai-hak dance of the Halam branch of Kuki people, and sangrai dance and owa dance of the Mog.[135] Alongside such traditional music, mainstream Indian musical elements such as Indian classical music and dance, Rabindra Sangeet are also practised.[136] Sachin Dev Burman, a member of the royal family, was a maestro in the filmi genre of Indian music.[137]

Hindus believe that Tripureshwari is the patron goddess of Tripura and an aspect of Shakti.[15]:30 Durga Puja, Kali Puja, Dolyatra, Ashokastami and the worship of the Chaturdasha deities are important festivals in the state. Some festivals represent confluence of different regional traditions, such as Ganga puja, Garia puja, Kharchi puja and Ker puja.[138][139] Unakoti, Pilak and Devtamura are historic sites where large collections of stone carvings and rock sculptures are noted.[129][140] Like Neermahal is a cultural Water Palace of this state. Sculptures are evidence of the presence of Buddhist and Brahmanical orders for centuries, and represent a rare artistic fusion of traditional organised religions and tribal influence.[141][142][143] The State Museum in the Ujjayanta Palace in Agartala has impressive galleries that depict the history and culture of Tripura through pictures, videos and other installations.

Tourism

Within its small geographical area, Tripura offers plenty of attractions for the tourists in the form of magnificent palaces ( Ujjayanta Palace and Kunjaban Palace at Agartala and Neermahal - Lake Palace at Melaghar ), splendid rock-cut carvings and stone images ( Unakoti near Kailashahar, Debtamura near Amarpur and Pilak in Belonia Sub-divisions ), important temples of Hindus and Buddhists including the famous Mata Tripureswari temple ( one of the 51 Pithasthans as per Hindu mythology ) at Udaipur, vast natural as well as artificial lakes namely Dumboor lake in Gandacherra subdivision, Rudrasagar at Melaghar, Amarsagar, Jagannath Dighi, Kalyan Sagar, etc. at Udaipur, the beautiful hill station of Jampui hill bordering Mizoram, wild life sanctuaries at Sepahijala, Gumti, Rowa and Trishna, eco parks created by forest department at Manu, Baramura, Ambassa and rich cultural heritage of Tribals, Bengalis and Manipuri communities residing in the state. The main attractions in Agartala are Ujjayanta Palace, State Museum, Heritage Park, Tribal Museum, Sukanta Academy, M.B.B. College, Laxminarayan Temple, Uma Maheswar Temple, Jagannath Temple, Benuban Bihar, Gedu Mian Mosque, Malancha Niwas, Rabindra Kanan, Purbasha, Handicrafts Designing Centre, Fourteen Goddess Temple, Portuguese Church etc.[144]

-

Heritage Park Stage Agartala

-

Neermahal, Agartala Tripura

-

Tripura has beautiful rock cut carvings and stone images at Unakoti is a profusion of rock-cut images, belonging to 11th or 12th century AD, intricate and finely executed.

-

Ujjayanta palace is the largest museum in Northeast India

Sports

Football and cricket are the most popular sports in the state. The state capital Agartala has its own club football championships every year in which many local clubs compete in a league and knockout format. Tripura participates as an eastern state team in the Ranji Trophy, the Indian domestic cricket competition. The state is a regular participant of the Indian National Games and the North Eastern Games.[145][146] In 2016, Dipa Karmakar from Agartala became the first ever female gymnast from India to qualify for the Olympics when she qualified for the women's artistic gymnastics event of 2016 Summer Olympics.[147]

See also

References

- ↑ http://tripura.gov.in/government/keycontact/2

- ↑ "Profile of Chief Minister". Government of Tripura. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ State of Literacy (PDF), censusindia.gov.in, retrieved June 20, 2015

- ↑ "Bengali and Kokborok are the state/official language, English, Hindi, Manipuri and Chakma are other languages". Tripura Official government website. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ↑ "Hill Tippera - Encyclopedia Britannica 1911".

- 1 2 "Tippera - Encyclopedia".

- 1 2 Das, J.K. (2001). "Chapter 5: old and new political process in realization of the rights of indigenous peoples (regarded as tribals) in Tripura". Human rights and indigenous peoples. APH Publishing. pp. 208–9. ISBN 978-81-7648-243-1.

- 1 2 Debbarma, Sukhendu (1996). Origin and growth of Christianity in Tripura: with special reference to the New Zealand Baptist Missionary Society, 1938–1988. Indus Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-7387-038-5.

- 1 2 Acharjya, Phanibhushan (1979). Tripura. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 1. ASIN B0006E4EQ6.

- ↑ Prakash (ed.), Encyclopaedia of North-east India, vol. 5, 2007, p. 2272

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India: from the stone age to the 12th century. Pearson Education India. p. 77. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- 1 2 Tripura district gazetteers. Educational Publications, Department of Education, Government of Tripura. 1975.

- ↑ Rahman, Syed Amanur; Verma, Balraj (5 August 2006). The beautiful India – Tripura. Reference Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-8405-026-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Hill Tippera – history" (GIF). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. 13: 118. 1909. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- 1 2 Bera, Gautam Kumar (2010). The land of fourteen gods: ethno-cultural profile of Tripura. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-8324-333-9.

- ↑ Sen, Kali Prasanna, ed. (2003). Sri rajmala volume – IV (in Bengali). Tribal Research Institute, Government of Tripura. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, Apurba Chandra (1930). Progressive Tripura. Inter-India Publications. p. 179. OCLC 16845189.

- ↑ Sircar, D.C. (1979). Some epigraphical records of the mediaeval period from eastern India. Abhinav Publications. p. 89. ISBN 978-81-7017-096-9.

- ↑ "AMC at a glance". Agartala Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "The state of human development". Tripura human development report 2007. Government of Tripura. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 3–6. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ Census of India, 1961: Tripura. Office of the Registrar General General. Government of India. 1967. p. 980.

- 1 2 Chakraborty, Kiran Sankar, ed. (2006). Entrepreneurship and small business development: with special reference to Tripura. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-8324-125-0.

- 1 2 Wolpert, Stanley A. (2000). A new history of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 390–1. ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3.

- 1 2 Kumāra, Braja Bihārī (1 January 2007). Problems of ethnicity in the North-East India. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 68–9. ISBN 978-81-8069-464-6. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ Sahaya, D.N. (19 September 2011). "How Tripura overcame insurgency". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Tripura assessment – year 2013". South Asia terrorism portal. Institute for Conflict Management. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- 1 2 "National highways and their length" (PDF). National Highways Authority of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Geology and mineral resources of Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura (PDF) (Report). Miscellaneous publication No. 30 Part IV. 1 (Part-2). Geological Survey of India, Government of India. 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ Seismic zoning map (Map). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Land, soil and climate". Department of Agriculture, Government of Tripura. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Annual plan 2011–12" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Government of Tripura. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ "Monthly and yearly quinquennial average rainfall in Tripura" (PDF). Statistical abstract of Tripura – 2007. Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. p. 13. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ "Hazard profiles of Indian districts" (PDF). National capacity building project in disaster management. UNDP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- ↑ "Monthly mean maximum & minimum temperature and total rainfall based upon 1901–2000 data" (PDF). India Meteorology Department. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ "State animals, birds, trees and flowers" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ Biogeographic classification of India: zones (Map). 1 cm=100 km. Wildlife Institute of India. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Forest and tree resources in states and union territories: Tripura" (PDF). India state of forest report 2011. Forest Survey of India, Ministry of Environment & Forests, Government of India. pp. 225–9. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ "Biodiversity". State of environment report of Tripura – 2002. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Forest". State of environment report of Tripura – 2002. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 Gupta, A.K. (December 2000). "Shifting cultivation and conservation of biological diversity in Tripura, Northeast India". Human Ecology. 28 (4): 614–5. doi:10.1023/A:1026491831856. ISSN 0300-7839. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Choudhury, A.U. (2010). The vanishing herds: the wild water buffalo. Gibbon Books & The Rhino Foundation, Guwahati, India, 184pp.

- ↑ Choudhury, A.U. (2010). Recent ornithological records from Tripura, north-eastern India, with an annotated checklist. Indian Birds 6(3): 66–74.

- 1 2 3 "Protected area network in India" (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. p. 28. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Choudhury, Anwaruddin (July–September 2009). "Gumti –Tripura's remote IBA" (PDF). Mistnet. Indian Bird Conservation Network. 10 (3): 7–8. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ Choudhury, Anwaruddin (April–June 2008). "Rudrasagar – a potential IBA in Tripura in north-east India." (PDF). Mistnet. Indian Bird Conservation Network. 9 (2): 4–5. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ "Four new districts, six subdivisions for Tripura". CNN-IBN. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ↑ "Four new districts for Tripura — plan for six more subdivisions to decentralise administration". The Telegraph. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ "New districts, sub-divisions and blocks for Tripura". Yahoo News. 28 December 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ "Tripura Legislative Assembly". Legislative Bodies in India. National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ↑ "About us". Tripura High Court. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Sharma, K Sarojkumar; Das, Manosh (24 March 2013). "New Chief Justices for Manipur, Meghalaya & Tripura high courts". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- 1 2 "State and district administration: fifteenth report" (PDF). Second Administrative Reforms Commission, Government of India. 2009. p. 267. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "About TTAADC". Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, Banikantha (1986). Tripura administration: the era of modernisation, 1870–1972. Mittal Publications. ASIN B0006ENGHO.

- ↑ "Manik Sarkar-led CPI(M) wins Tripura Assembly elections for the fifth straight time". CNN-IBN. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

The Left Front has been in power since 1978, barring one term during 1988 to 1993.

- ↑ Paul, Manas (24 December 2010). "Tripura terror outfit suffers vertical split". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

ATTF was an off shoot of All Tripura Tribal Force formed during the Congress-TUJS coalition government-1988-1993 in Tripura

- ↑ "CPI(M) win in Tripura reflects re-emergence of Left Parties". The Indian Express. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ Singh, M.P.; Saxena, R. (2011). Indian politics constitutional foundations and institutional functioning. PHI Learning. pp. 294–5. ISBN 978-81-203-4447-1.

- 1 2 Chadha, Vivek (2005). Low intensity conflicts in India: an analysis. Sage. ISBN 978-0-7619-3325-0.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Harihar (2004). "Communist party of India (Marxist): from rebellion to governance". In Mitra, Subrata Kumar. Political Parties in South Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 88–9. ISBN 978-0-275-96832-8.

- ↑ "Secessionist Movements of Tripura" in Prakash, Terrorism in India's North-east vol. 1, 2008, [books.google.ch/books?id=Sb1ryB8CVvIC&pg=PA955 955ff.]

- ↑ Anshu Lal (29 May 2015). "AFSPA removed in Tripura after 18 years: Here's why it was enforced and why it's gone now". Firstpost India. Firstpost. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Gross state domestic product of Tripura". North Eastern Development Finance Corporation. Retrieved 3 April 2012.(subscription required)

- 1 2 "Economic review of Tripura 2009–2010" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. p. 9. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 77–82. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 8–10. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Tripura at a glance – 2010" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. Section: Agriculture 2009–10. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- 1 2 "The economy". Tripura human development Report 2007 (PDF). Government of Tripura. 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 133–8. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 14–6. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Tata Trust signs MoU with Tripura Govt. for sustainable development". Tripura Infoway.

- ↑ ONGC makes three oil, gas discoveries UPI (March 2013)

- ↑ "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 228–30. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- 1 2 Ali, Syed Sajjad (5 March 2013). "Bangladesh violence hits border trade in Tripura". The Hindu. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Dey, Supratim (9 February 2011). "Tripura-Bangladesh border fencing to boost trade". Business Standard. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- 1 2 Saha, Arunadoy (2004). Murayama, Mayumi; Inoue, Kyoko; Hazarika, Sanjoy, eds. "Sub-regional relations in the eastern South Asia: with special focus on India's North Eastern region" (PDF). Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ "tripurainfo". Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Industrial Growth Centers". Tripura Industrial Development Corporation Limited, Government of Tripura.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 195–201. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- 1 2 Bareh, Hamlet (2001). Encyclopaedia of North-East India: Tripura. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-795-5.

- ↑ "Management of Indo-Bangladesh border" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ "How to reach Tripura by international bus service". Tripura Tourism Development Corporation, Government of Tripura. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Paul, Manas (9 September 2003). "Dhaka-Agartala bus service agreement signed". The Times of India. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ "Progress of Akhaura-Agartala rail link to be reviewed on December 4". The Economic Times. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Soondas, Anand (29 April 2005). "Drug smuggling rampant on Tripura-Bangla border". The Times of India. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "List of newspapers categorized by the state Government as per advertisement guidelines – 2009". Department of Information, Cultural Affairs and Tourism, Government of Tripura. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- 1 2 "Impact and penetration of mass media in North East and J and K regions" (PDF). Indian Institute of Mass Communication. March 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ↑ Iqbal, Naveed (22 June 2013). "President inaugurates ONGC Tripura power plant". The Indian Express. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ PM Modi inaugurates second unit of Palatana power project in Tripura India Today

- ↑ BHEL commissions second gas-based power plant in Tripura BHEL, The Economic Times (November 2014)

- ↑ ONGC Tripura Power Project (2014)

- 1 2 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 190–2. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Commissioning of Monarchak power project uncertain: NEEPCO". Business Standard. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ PM dedicates power plant in Tripura The Morung Express (1 December 2014)

- 1 2 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 193–5. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Urea plant to become operational in Tripura in 3 years The Economic Times (June 2014)

- ↑ ONGC sets sight on Bangladesh for fertiliser sale from Tripura Business Standard (June 2014)

- ↑ "Land of water, no more". India Water Portal.

- 1 2 3 4 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 232–3. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Tripura Tribal Welfare Residential Educational Institutions Society (TTWREIS)".

- 1 2 "Boards of secondary & senior secondary education in India". Department of School Education and Literacy, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Singh, Y.K.; Nath, R. History of Indian education system. APH Publishing. pp. 174–5. ISBN 978-81-7648-932-4.

- ↑ "Agartala Government Medical College website".

- ↑ "Tripura Medical College and Hospital website".

- ↑ "List of Professional Colleges in Tripura". Tripura University.

- 1 2 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. p. 251. Retrieved 20 April 2012. These data are based on Sample Registration System of Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India.

- ↑ "Health care centres of Tripura". Government of Tripura. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- 1 2 "Economic review of Tripura 2010–11" (PDF). Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. pp. 254–5. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International (September 2007). "National Family Health Survey (NFHS – 3), 2005–06" (PDF). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. p. 438. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Malaria deaths put Tripura on high alert". The Hindu.

- ↑ "Census population" (PDF). Census of India. Ministry of Finance India. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Provisional population totals paper 2 of 2011: Tripura" (PDF). Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Provisional population totals at a glance figure : 2011 – Tripura". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "HDI and GDI estimates for India and the states/UTs: results and analysis" (PDF). Gendering human development indices: recasting the gender development index and gender empowerment measure for India. Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. 2009. pp. 30–2. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau (2011). "Crime in India-2011" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. p. 246.

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau (2011). "Crime in India-2011" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. p. 200.

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau (2010). "Crime in India-2010" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tripura data highlights: the scheduled tribes" (PDF). Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages". Census of India. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "Census Reference Tables, A-Series - Total Population". Census of India. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- 1 2 "State wise scheduled tribes: Tripura" (PDF). Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Report of the commissioner for linguistic minorities: 47th report (July 2008 to June 2010)" (PDF). Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. 2011. pp. 116–21. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ "Just 4 people keep a language alive". The Hindu. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ "Population by religion community - 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Census of India – Religious Composition". Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Das, J.K (2001). Human rights and indigenous peoples. APH Publishing. p. 215. ISBN 978-81-7648-243-1.

- 1 2 3 Chaudhury, Saroj (2009). "Tripura: a composite culture" (PDF). Glimpses from the North-East. National Knowledge Commission. pp. 55–61. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 Paul, Manas (19 April 2010). The eyewitness: tales from Tripura's ethnic conflict. Lancer Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-935501-15-2.

- ↑ Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (15 November 2002). The territories and states of India. Psychology Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-85743-148-3.

- ↑ Sircar, Kaushik (2006). The consumer in the north-east: new vistas for marketing. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-0023-5.

- ↑ Prakash (ed.), Encyclopaedia of North-east India, vol. 5, 2007, p. 2268

- ↑ "Handicrafts". Government of Tripura. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 "The folk dance and music of Tripura" (PDF). Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Hazarika, Sanjoy (2000). Rites of passage: border crossings, imagined homelands, India's east and Bangladesh. Penguin Books India. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-14-100422-8.

- ↑ Ganti, Tejaswini (24 August 2004). Bollywood: a guidebook to popular Hindi cinema. Psychology Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-415-28853-8.

- ↑ Sharma, A.P. (8 May 2010). "Tripura festival". Famous festivals of India. Pinnacle Technology. ISBN 978-1-61820-288-8.

- ↑ "Fairs and festivals". Government of Tripura. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ "Tripura sculptures, rock images speak of glorious past". Deccan Herald. 25 July 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Chauley, G. C. (1 September 2007). Art treasures of Unakoti, Tripura. Agam Kala Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7320-066-3.

- ↑ North East India History Association. Session (2003). Proceedings of North East India History Association. The Association. p. 13.

- ↑ Chaudhuri, Saroj; Chaudhuri, Bikach (1983). Glimpses of Tripura. 1. Tripura Darpan Prakashani. p. 5. ASIN B0000CQFES.

- ↑ "Travel and Tourism". Tripura State Portal. Directorate of Information Technology, Government of Tripura. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ↑ "34th National Games medal tally". Ranchi Express. 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ "Northeastern games". Sports Authority of India. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ "Dipa Karmakar becomes 1st Indian woman gymnast to qualify for Rio Olympics". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 19 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

Further reading

- "The Agony of Tripura". By Mr. J.D. Mandal (2003)

- Gan-Chaudhuri, Jagadis (1 January 1985). An anthology of Tripura. Inter-India Publications. OCLC 568730389.

- Roychoudhury, Nalini Ranjan (1977). Tripura through the ages: a short history of Tripura from the earliest times to 1947 A.D. Bureau of Research & Publications on Tripura. OCLC 4497205.

- Bhattacharjee, Pravas Ranjan (1993). Economic transition in Tripura. Vikas Pub. House. ISBN 978-0-7069-7171-2.

- Palit, Projit Kumar (1 January 2004). History of religion in Tripura. Kaveri Books. ISBN 978-81-7479-064-4.

- DebBarma, Chandramani (2006). Glory of Tripura civilisation: history of Tripura with Kok Borok names of the kings. Parul Prakashani. OCLC 68193115.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tripura. |

|

Sylhet Division, |

Assam |  | |

| Chittagong Division, |

|

Mizoram | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Chittagong Division, |