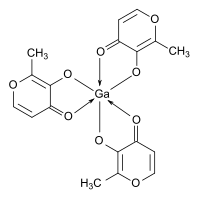

Gallium maltolate

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Tris(3-hydroxy-2-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one)gallium | |

| Identifiers | |

| 108560-70-9 | |

| UNII | 17LEI49C2G |

| Properties | |

| Ga(C6H5O3)3 | |

| Molar mass | 445.03 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to pale beige crystalline solid or powder |

| Density | 1.56 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 220 °C (decomposes) |

| 24(2) mM; 10.7(9) mg/mL (25 °C) | |

| Structure | |

| Orthorhombic; space group Pbca | |

| Distorted octahedral | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Gallium maltolate is a coordination complex consisting of a trivalent gallium cation coordinated to three maltolate ligands. The compound is undergoing clinical and preclinical testing as a potential therapeutic agent for cancer, infectious disease, and inflammatory disease.[1][2][3][4] It appears to have low toxicity when administered orally, without the renal toxicity observed for intravenously administered gallium nitrate. The lower toxicity probably results because gallium absorbed into the body from oral gallium maltolate becomes nearly entirely protein bound, whereas gallium from intravenous gallium nitrate tends to form anionic gallium hydroxide (Ga(OH)4−; gallate) in the blood, which is rapidly excreted in the urine and may be renally toxic.[1] A cosmetic skin cream containing gallium maltolate is marketed under the name Gallixa.

Chemical properties

In aqueous solutions, gallium maltolate has neutral charge and pH, and is stable between about pH 5 and 8. It has significant solubility in both water and lipids (octanol:water partition coefficient = 0.41).[1]

Research and pharmaceutical development

Pharmaceutical compositions and uses of gallium maltolate were first patented by Lawrence R. Bernstein.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

Christopher Chitambar and his associates at the Medical College of Wisconsin have found that gallium maltolate is active against several lymphoma cell lines, including those resistant to gallium nitrate.[3]

Gallium maltolate is able to deliver gallium with high oral bioavailability: the bioavailability is several times higher than that of gallium salts such as gallium nitrate and gallium trichloride.[1] In vitro studies have found gallium to be antiproliferative due primarily to its ability to mimic ferric iron (Fe3+). Ferric iron is essential for DNA synthesis, as it is present in the active site of the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase, which catalyzes the conversion of ribonucleotides to the deoxyribonucleotides required for DNA. Gallium is taken up by the rapidly proliferating cells, but it is not functional for DNA synthesis, so the cells cannot reproduce and they ultimately die by apoptosis. Normally reproducing cells take up little gallium (as is known from gallium scans), and gallium is not incorporated into hemoglobin, accounting for the relatively low toxicity of gallium.[11]

Gallium has been repeatedly shown to have anti-inflammatory activity in animal models of inflammatory disease.[2][11][12] Orally administered gallium maltolate has demonstrated efficacy against two types of induced inflammatory arthritis in rats.[12] Experimental evidence suggests that the anti-inflammatory activity of gallium may be due, at least in part, to down-regulation of pro-inflammatory T-cells and inhibition of inflammatory cytokine secretion by macrophages.[2][11][12] Because many iron compounds are pro-inflammatory, the ability of gallium to act as a non-functional iron mimic may contribute to its anti-inflammatory activity.[2]

Gallium maltolate is being studied as a potential treatment for primary liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma; HCC). In vitro experiments demonstrated efficacy against HCC cell lines[4] and one clinical case report produced encouraging results.[13]

The activity of gallium against infection-related biofilms, particularly those caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is being studied by Pradeep Singh at the University of Washington, and by others, who have reported encouraging results in mice.[14][15] Pulmonary P. aeruginosa biofilms are responsible for many fatalities in cystic fibrosis and immunocompromised patients; in general, bacterial biofilms are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality.[16] In related research, locally administered gallium maltolate has shown potent efficacy against P. aeruginosa in a mouse burn/infection model.[17]

Oral gallium maltolate is also being investigated as a treatment for Rhodococcus equi foal pneumonia, a common and often fatal disease of newborn horses. R. equi can also infect humans with AIDS or who are otherwise immunocompromized. The veterinary studies are being conducted by researchers at Texas A&M University, led by Ronald Martens, Noah Cohen, and M. Keith Chaffin.[18][19]

Topically applied gallium maltolate has been studied in case reports for use in neuropathic pain (severe postherpetic neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia).[12] It has been hypothesized that any effect on pain may be related to gallium's anti-inflammatory mechanisms, and possibly from its interactions with certain matrix metalloproteinases and substance P, whose activities are zinc-mediated and which have been implicated in the etiology of pain.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Bernstein, L.R.; Tanner, T.; Godfrey, C.; Noll, B. (2000). "Chemistry and pharmacokinetics of gallium maltolate, a compound with high oral gallium bioavailability". Metal Based Drugs. 7 (1): 33–48. doi:10.1155/MBD.2000.33. PMC 2365198

. PMID 18475921.

. PMID 18475921. - 1 2 3 4 Bernstein, L.R. (2005). "Therapeutic gallium compounds" (PDF). In Gielen, M.; Tiekink, E.R.T. Metallotherapeutic Drugs and Metal-Based Diagnostic Agents: The Use of Metals in Medicine. New York: Wiley. pp. 259–277. ISBN 978-0-470-86403-6.

- 1 2 Chitambar, C.R.; Purpi, D.P.; Woodliff, J.; Yang, M.; Wereley J.P. (2007). "Development of Gallium Compounds for Treatment of Lymphoma: Gallium Maltolate, a Novel Hydroxypyrone Gallium Compound, Induces Apoptosis and Circumvents Lymphoma Cell Resistance to Gallium Nitrate" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322 (3): 1228–1236. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.126342. PMID 17600139.

- 1 2 Chua, M.-Z.; Bernstein, L.R.; Li, R.; So, S.K. (2006). "Gallium maltolate is a promising chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma" (PDF). Anticancer Research. 26 (3A): 1739–1743. PMID 16827101.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 5,574,027

- ↑ U.S. Patent 5,747,482

- ↑ U.S. Patent 6,048,851

- ↑ U.S. Patent 6,087,354

- ↑ U.S. Patent 8,293,268

- ↑ U.S. Patent 8,293,787

- 1 2 3 Bernstein, L.R. (1998). "Mechanisms of therapeutic activity for gallium" (PDF). Pharmacol. Rev. 50 (4): 665–682. PMID 9860806.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bernstein, Lawrence (2013). "Gallium, therapeutic effects" (PDF). In Kretsinger, R.H.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A. Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins. New York: Springer. pp. 823–835. ISBN 978-1-4614-1532-9.

- ↑ Bernstein, L.R.; van der Hoeven, J.J.; Boer, R.O. (2011). "Hepatocellular carcinoma detection by gallium scan and subsequent treatment with gallium maltolate: rationale and case study" (PDF). Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (6): 585–590. doi:10.2174/187152011796011046. PMID 21554205.

- ↑ Kaneko, Y.; Thoendel, M.; Olakanmi, O.; Britigan, B.E.; Singh, P.K. (2007). "The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity". J. Clin. Invest. 117 (4): 877–888. doi:10.1172/JCI30783. PMC 1810576

. PMID 17364024.

. PMID 17364024. - ↑ Wirtz, U.F.; Kadurugamuwa, J.; Bucalo, L.R.; Sreedharan, S.P. (2006). Efficacy of gallium maltolate in a mouse model for Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic urinary tract infection (PDF). American Society for Microbiology 106th general meeting. Orlando, Florida. Poster A-074.

- ↑ Parsek, M.; Singh, P. (2003). "Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57: 677–701. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090720. PMID 14527295.

- ↑ DeLeon K.; Balldin F.; Watters C.; Hamood A.; Griswold J.; Sreedharan S.; Rumbaugh K.P. (2009). "Gallium maltolate treatment eradicates Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in thermally injured mice". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 53 (4): 1331–1337. doi:10.1128/AAC.01330-08. PMC 2663094

. PMID 19188381.

. PMID 19188381. - ↑ Harrington, J.R.; Martens, R.J.; Cohen, N.D.; Bernstein, L.R. (2006). "Antimicrobial activity of gallium against virulent Rhodococcus equi in vitro and in vivo". J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 29 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2006.00723.x. PMID 16515666.

- ↑ Martens, R.J.; Mealey, K.; Cohen, N.D.; Harrington, J.R.; Chaffin, M.K.; Taylor, R.J.; Bernstein, L.R. (2007). "Pharmacokinetics of gallium maltolate after intragastric administration in neonatal foals". Am. J. Vet. Res. 68 (10): 1041–1044. doi:10.2460/ajvr.68.10.1041. PMID 17916007.