Galatea 2.2

|

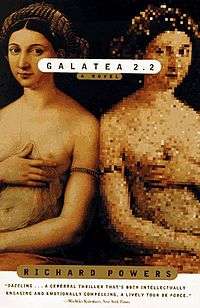

The cover of Galatea 2.2 incorporates the Raphael painting La fornarina. | |

| Author | Richard Powers |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Pseudo-autobiography, science fiction |

| Publisher | Harper Perennial |

Publication date | 1995 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

Galatea 2.2 is a 1995 pseudo-autobiographical novel by Richard Powers and a contemporary reworking of the Pygmalion myth.[1] The book's narrator shares the same name as Powers, with the book referencing events and books in the author's life while mentioning other events that may or may not be based upon Powers' life.

Plot summary

The main narrative tells the story of Powers' return to his alma mater – referred to in the novel as simply "U.", but clearly based on the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the school Powers attended and teaches at as a professor – after he has ended a long and torrid relationship with a loving but volatile woman, referred to as "C." Powers is an in-house author for the university, and lives for free for one year. He finds himself unable to write any more books, and spends the first portion of the novel attempting to write, but never getting past the first line.

Powers then meets a computer scientist named Philip Lentz. Intrigued by Lentz's overbearing personality and unorthodox theories, Powers eventually agrees to participate in an experiment involving artificial intelligence. Lentz bets his fellow scientists that he can build a computer that can produce an analysis of a literary text that is indistinguishable from one produced by a human. It is Powers' task to "teach" the machine. After going through several unsuccessful versions, Powers and Lentz produce a computer model (dubbed "Helen") that is able to communicate like a human. It is not clear to the reader or to Powers whether she is simulating human thought, or whether she is actually experiencing it. Powers tutors the computer, first by reading it canonical works of literature, then current events, and eventually telling it the story of his own life, in the process developing a complicated relationship with the machine.

The novel also consists of extensive flashbacks to Powers' relationship with C., from their first meeting at U., to their bohemian life in Boston, to their move to C.'s family's town in the Netherlands.

The novel culminates with Helen being unable to bear the realities of the world, and "leaving" Powers. She asks Powers to "see everything" for her, and subsequently shuts herself down. Her exit from the world forces Powers to experience a rebirth. In addition, Powers realizes that he was Lentz's experiment: would he or wouldn't he be able to teach a computer? Through the transformation he experiences, he is suddenly able to interact with the world, and he can write again.

Characters in Galatea 2.2

- Richard Powers: The central character of the novel, Powers shares certain traits and experiences with the novelist without being a complete copy of the author.

- Lentz: Lentz is a sarcastic and brilliant researcher and scientist. He creates Helen in an effort to explore the workings of the human brain, to somehow discover how a mere biological accident could so destroy the woman he loved.

- Helen: Helen is the creation of Lentz and Richard; Lentz builds her, and Richard educates her. She is a net, spread out over innumerable computers, and she is taught using the literary canon. Only when she is exposed to reality—the murder, rage, etc. that characterize daily news and the human world—does she realize fully that she does not belong nor does she wish to belong in this world. One of the central arguments of the book comes from Helen and whether she has human emotions, or is simply simulating human emotion.

Reviews and critiques

Reception for the book has been mostly positive,[2] with the Los Angeles Times praising the novel.[3] The New York Times wrote that Galatea 2.2 was "complex" and a "heady and provocative experiment".[4] The Washington Times expressed that the book "may not be the easiest to access, but will prove as enchanting as any."[5]

Awards and nominations

- Finalist, 1995 National Book Critics Circle Award

- Time Magazine Best Books of the Year, 1995

- New York Times Notable Book, 1995

Publication history

- Galatea 2.2. NY: Farrar Straus & Giroux. London: Little, Brown / Abacus, 1995. Designed by Fritz Metsch; jacket design by Michael Ian Kaye. 329 p. (ISBN 0374199485)

- Galatea 2.2. 1st Harper Perennial ed. NY: HarperPerennial & HarperCollins Canada, Ltd, 1996. 336 p. (ISBN 0060976926.)

- Galatea 2.2. Books On Tape, 1996. Performed By Michael Kramer, Nine sound cassettes, 810 minutes, Single Reader, Full Length. (ISBN 0736633499)

- Galatea 2.2. London: Abacus, 1996. 329 p. (ISBN 0349107718 (pbk) .)

- Galatea 2.2. Netherlands: Uitgeverij Contact, 1997. 365 p. (ISBN 9025406203) Translation into Dutch by Niek Miedema and Harm Damsma. Cover design: Jos Peters; cover photo: Zefa.

- Galatea 2.2. Germany: Amann Verlag, 1997. Jacket design by Wolfsfeld Design Factory. Translation into German.

- Galatea 2.2. France: Editions du Seuil, 1997 Translation into French

- Galatea 2.2. Barcelona: Mondadori, 1997. 370 p. (ISBN 8439701454) Translation into Spanish by Cristóbal Pera. Design: Graficas Huertas, S.A

- Galatea 2.2. Galatea 2.2. Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2000. 459 p. (ISBN 3596142768) Translation into German by Werner Schmitz.

- Galatea 2.2. Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 2001. 403 p. (ISBN 4622048183)<

- Galatea 2.2. Roma: Fanucci, 2003.393 p. (ISBN 88-347-0929-2) Translation into Italian by Luca Briasco.

- Forthcoming editions in French (Editions du Seuil); Hebrew (Am Oved); Portuguese (Nova Fronteira)

See also

References

- ↑ Harper, John (Jul 9, 1995). "PYGMALION' FOR THE COMPUTER AGE". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Cobb, William (July 23, 1995). "Picture a brain heading south". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Eder, Richard (June 18, 1995). "More Human Than Human : Is a brain-like computer the result of creation or programming?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Cohen, Robert (July 23, 1995). "Pygmalion in the Computer Lab". New York Times. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "Fictional return to `age of reading'". Washington Times. July 23, 1995. Retrieved 6 September 2012.