Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont

Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont (April 1679 – 1734) was a French explorer who documented his travels on the Missouri and Platte rivers in North America and made the first European maps of these areas in the early 18th century. He wrote two accounts of his travels, which included descriptions of the Native American tribes he encountered. In 1723, he established Fort Orleans, the first European fort on the Missouri River, near the mouth of the Grand River and present-day Brunswick, Missouri. In 1724, he led an expedition to the Great Plains of Kansas to establish trading relations with the Padouca (Apache Indians).

Early life and education

He was born in Cerisy-Belle-Étoile in central Normandy. At the age of 19, Bourgmont was found guilty in 1698 of poaching on the land of the Monastery of Belle-Etoile. He did not pay the 100-livres fine. He is believed to have left for New France settlements in North America that year to escape imprisonment for failing to pay the fine.

Early career in North America

In 1702 Bourgmont was reported to be with Charles Juchereau de St. Denys and the Troupes de la marine, who were setting up a tannery for buffalo hides at the mouth of the Ouabache River (Wabash River) on the Ohio River. The tannery closed in 1703 and Bourgmont moved to Quebec.

In 1705 on orders from Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, Bourgmont moved to Fort Pontchartrain at present-day Detroit, Michigan, where he assumed command in 1706. In March 1706 a group of Ottawa attacked a group of Miami outside the fort. Soldiers fired from the fort and killed a French priest and sergeant who had been outside the walls, in addition to 30 Ottawa. Bourgmont was severely criticized for his handling of the incident. When Cadillac visited the fort in August, Bourgmont and other members of the garrison were reported as having deserted their post.[1]

From 1706 to 1709, Bourgmont and other deserters lived as coureurs des bois (illegal traders, literally, "wood runners") around the Grand River and Lake Erie. In 1709 one of the deserters, Betellemy Pichon, known as La Roze, was captured. He testified that two of the deserters had drowned, and that one had been shot and eaten by the starving party. La Roze was sentenced to have his "head broken" until he died.[1]

In 1712 Bourgmont returned to Fort Pontchartrain, where he helped the Algonquian, Missouria, and Osage peoples in their fight against the Fox. Bourgmont was still an outlaw, subject to arrest. However, he traveled widely on the frontier and little effort was made to arrest him. About 1713, Cadillac apparently pardoned him because his knowledge of Indian tribes and territory were of great utility to the French.[2]

Consorts, marriages, and families

Bourgmont had an affair with a married woman, Madame Tichenet, known as "La Chenette, at Fort Pontchartrain. After his desertion in 1706, the couple met up and lived among a group of deserters on an island in Lake Erie. La Chenette, was the daughter of a French man and an Indian woman. The couple separated and La Chenette turned up at the English town of Albany, New York in 1709 where she worked as an interpreter for the governor and lived among the English for 12 years.[3]

In 1712, Bourgmont met the daughter of the chief of the Missouria tribe near Fort Pontchartrain and accompanied her back to the Missouria village at the mouth of the Grand River in Missouri, thus beginning his long-term residence and close relationships with the Missouria. He had children with her, including a son, "le Petit Missouria," born about 1714. In 1713, Bourgmont and two other traders, also traveling with their Indian wives, visited Illinois. "He scandalized the missionaries, rattled the authorities, and even angered certain exalted personages at the court of Louis XIV." Another order for his arrest came out from Paris, but Cadillac ignored it.[4]

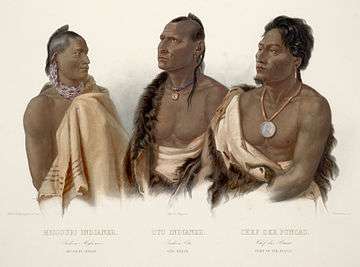

In May 1721, after returning to Paris and gaining honors for his explorations and reports, Bourgmont married Jacqueline Bouvet des Bordeaux in his home village of Cérisy Belle-Étoile, Normandy. He left in June to return to New Orleans. In 1725, he accompanied a delegation of four leaders from the Illinois, Missouria, Osage, and Oto tribes on a visit to France. His Missouria wife was also part of the delegation. While in France, Bourgmont's Missouria wife was baptized and married to Bourgmont's close colleague, Sergeant Dubois, who returned with his new wife and the other Indians to North America. Bourgmont stayed in France, joining his French wife Jacqueline in Normandy. Sergeant Dubois was later killed by Indians and the Missouria woman married a captain of militia. She was still alive, living in Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1752. The fate of Bourgmont's Missouria son is unknown, as the last record of him is in 1724.[5]

Bourgmont and his French wife, Jacqueline, had four children, all of whom died young. Another women enters the story during Bourgmont's French marriage. In 1728 Marie Angelique, "the Padouca slave" of Bourgmont, was baptized in Cérisy. Four years later, in 1732, she married. She had a six-week-old son who was legitimized by the wedding ceremony.[6]

Hero of the French state

In 1713 Bourgmont began writing Exact Description of Louisiana, of Its Harbors, Lands and Rivers, and Names of the Indian Tribes That Occupy It, and the Commerce and Advantages to Be Derived Therefrom for the Establishment of a Colony. In March 1714 he traveled to the mouth of the present-day Platte River (which he named the Rivière Nebraskier, after the Otoe tribe name for "flat water"). He wrote The Route to Be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River This account reached the cartographer Guillaume Delisle, who noted that it was the first documented report of travels that far north on the Missouri.[1]

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville replaced Cadillac as commandant. On September 25, 1718, he recommended that Bourgmont receive the Cross of Saint Louis for service to France, for the value of his explorations and documentation of river travel. In September 1719, the Council of the Colony of Louisiana also recognized Bourgmont's work with Native Americans with a resolution of praise.

Bourgmont described his knack for dealing with the tribes:

- For me with the Indians nothing is impossible. I make them do what they have never done.[7]

Tribes were said to have valued the products Bourgmont offered, as he traded gunpowder, guns, kettles, and blankets. The Spanish were said to trade few horses, knives, and "inferior axes." [8]

Officials sent Bourgmont to bring the chiefs of several tribes to Dauphin Island, a French base in present-day Alabama, for a meeting. All of the chiefs except one died en route. Bourgmont escorted the surviving chief back to his homeland and then returned to the (new) settlement of New Orleans. He was paid 4,279 livres for his work.

In June 1720 he and his mixed-race son traveled to Paris, where they were greeted as heroes. News had arrived that Native American tribes friendly to Bourgmont had defeated the Spanish Villasur expedition. In July Bourgmont was commissioned as a captain in the French army. In August 1720 he was named "Commandant of the Missouri River." In exchange for Letters of Nobility, he was commissioned to build a fort on the Missouri River and negotiate with the tribes to allow peaceful French commerce.

Expedition to the Great Plains

Bourgmont established Fort Orleans in early 1723 as the military headquarters for the Missouri River. From Fort Orleans, near the mouth of the Grand River, he planned to visit the Padouca on the Great Plains and open a trade route to reach the Spanish colony in New Mexico (larger than the current state). Bourgmont sought aid from the Kaw to facilitate his expedition. He sent 22 Frenchmen and Canadians by boat from Fort Orleans to the Kaw village on the Missouri near Doniphan, Kansas with supplies and gifts. Accompanied by 10 French colonists, 100 Missouri and 64 Osage, he traveled by land.[9] Bourgmont's visit to the Kaw was the first official French visit, although many French traders, including he, had visited them during the previous 20 years. Some of the Kaw had also likely journeyed to trade in Kaskaskia, a French colonial village then on the east side of the Mississippi in present-day Illinois.

Bourgmont's party reached the Kaw village on July 8, 1724. It was large, with at least 1,500 persons.[10] The Kaw greeted him as an old colleague, honoring him with innumerable speeches and feasts. When the talk turned to trade, the Kaw were hard bargainers. Bourgmont wanted to buy horses from them. With only five horses to trade, they extracted a high price. This indicates that horses were still rare on the eastern border of the Plains. The Kaw also traded six slaves (likely American Indians of other tribes captured in battle), food, furs, and skins. On July 24, Bourgmont, his party of French, Missouri, and Osage, and most of the Kaw left on their expedition to visit the Padouca.

Due to the heat, Bourgmont became ill, and the entire party of over 1,000 people returned to the Kaw village. Bourgmont sent an emissary ahead to contact the Padouca and tell them he would soon be coming, and that he would bring two Padouca slaves to be returned to the tribe as an expression of good will. Bourgmont's emissary found the Padouca in western Kansas, most likely in the region of the Quartelejo in Scott County. It had become a refuge for Indians fleeing the Spanish in New Mexico. Eight villages with about 600 men in total lived in the area. They agreed to relocate closer to the Kaw village in order to meet Bourgmont when he was able to resume his journey. Five Padouca returned to the Kaw village as guides.

Recovered from his illness, on October 8 Bourgmont resumed his journey to the Padouca. His party was much smaller and more nimble: 15 French and Métis, including Bourgmont's half-Missouria son; the five Padoucas, seven Missouria, five Kaw, four Otoe, and three Iowa. The Osage were not recorded as part of this smaller expedition. Ten horses carried the baggage. The party proceeded southwest and on October 11 at the crossing of the Kansas River, near present-day Rossville, Bourgmont recorded seeing buffalo. The expedition passed through innumerable buffalo, a hunter's paradise. They recorded 30 herds in one day, each herd consisting of 400-500 buffalo. Bourgmont wrote, "Our hunters kill as many as they please."[11] Deer were also abundant. In one day they saw more than 200, plus numerous turkeys near the streams.

The Padouca

On October 18, Bourgmont encountered the Padouca. Eighty of the Padouca rode out on horses to meet the French and took them back to the camp. The number of horses indicates that the Padouca at this time held more horses than did the Kaw and the other Indians living further east. The identity of the people whom Bourgmont met with has been much debated by historians. The French later referred to the Comanche as Padouca. Most historians and anthropologists have come to agree that Bourgmont’s Padouca were likely the Apache Indians.[12]

Bourgmont was given an honored welcome. With his son and two other French explorers, he was seated on a buffalo robe; they were carried to the tent (tipi?) of the Padouca chief for a great feast. The next day Bourgmont assembled his trade goods and divided them into lots. The following is the list:

"one pile of fusils [guns], one of sabers, one of pickaxes, one of axes, one of gunpowder, one of balls, one of red Limbourg cloth, another of blue Limbourg cloth, one of mirrors, one of Flemish knives, two other piles of another kind of knives, one of shirts, one of scissors, one of combs, one of gunflints, one of wadding extractors, six portions of vermillion, one lot of awls, one of large hawk beads, one of beads of mixed sizes, one of small beans, one of fine brass wire, another of heavier brass wire for making necklaces, another of rings, and another of vermillion cases."[13]

The Padouca (or Apache) had never seen such a variety of European goods. They were frightened of the guns.[14]

Bourgmont assembled 200 of the Apache chiefs and discussed the need for peace among all tribes. He implored them to allow the French traders to pass through their lands en route to the Spanish settlements in New Mexico. Next, he invited the chiefs to take what they wanted of the merchandise.

He estimated that the village contained 140 dwellings, about 800 men, more than 1,500 women, and about 2,000 children. The imbalance between men and women indicates that the life of an Apache man was hazardous.[13] The dwellings were large enough to house 30 people to live in each. The Apache chief said that he had twelve villages under his control and together four times the number of people as in this village, or about 16,000. The Apache lived in a large territory extending more than 200 leagues (520 miles).

Bourgmont wrote that the Apache maintained permanent villages. They sent out regular hunting parties, in groups of 50-100 households. As one hunting party returned, another would leave, so that the village was occupied at all times. They apparently journeyed up to five or six days from their village to hunt. The Apache sowed a little corn and pumpkins. They obtained tobacco and horses from trade with the Spanish in New Mexico, in exchange for tanned buffalo skins. It is unclear whether the Spanish ventured out on the plains to visit the Apache villages, or whether the Apaches traveled to the Spanish settlements. The latter seems more likely, although Spaniards may have gone out occasionally to meet the Apache who lived relatively near to their settlements. The explorer noticed that the Apache living furthest from the Spanish settlements still used flint knives for skinning buffalo and felling trees, an indicator that not much European trade had reached them.

The Apache were hospitable; they feasted and fêted Bourgmont and his group for three days before the French party turned toward home on October 22. By October 31, Bourgmont had reached the Kaw village again. Traveling down the Missouri in circular "bullboats", made of buffalo hides stretched over a framework of saplings, the party reached Fort Orleans on November 5.[15] Bourgmont thought his expedition had been successful, but little came of it. Within about a decade, the Apache whom he had met in Kansas were gone, pushed south by an aggressive tribe migrating from the Rocky Mountains and sweeping all before them: the Comanche.

The location of the Padouca

Scholars examining documents and geography have determined that the Apache village was probably located on the Little Arkansas River near Lyons, Kansas—the same location where Francisco Vásquez de Coronado had found Quivira 173 years earlier while hunting for tribes with gold.[16] But, the Wichita Indians, whom Coronado met in Quivira, were no longer there. It appears that they had been pushed south and east by the Apache, who, in their turn, would be pushed south by the Comanche.

Return to France

In 1725 Bourgmont was authorized to invite and accompany representatives of the tribes to Paris. The chiefs were to be shown the wonders and power of France, including a visit to Versailles, Château de Marly and Fontainebleau, hunting in the royal forest with Louis XV, and seeing an opera. His Missouria wife was listed officially as a servant.

In late 1725 the tribes' leaders and his Missouria wife returned to North America. Bourgemont stayed in Normandy with his French wife, where he had been elevated to écuyer (squire).

The French did not continue to support Fort Orleans, and it was abandoned in 1726. Bourgmont died in France in 1734.

References

- 1 2 3 Dan Hechenberger, "Etienne de Véniard sieur de Bourgmont - A timeline", The Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery, National Park Service

- ↑ Norall, Frank. Bourgmont, Explorer of the Missouri, 1698-1725 Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988, p. 24

- ↑ Norall, p. 16-17

- ↑ Norall, p. 17, 42

- ↑ Norall, pp. 87-88

- ↑ Norall, p. 88

- ↑ Colin Gordon Calloway, New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America, Marie Angelique ISBN 0-8018-5959-X, 1998]

- ↑ Colin G. Calloway, One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West Before Lewis And Clark ISBN 0-8032-1530-4, 2003

- ↑ Norall, pp 51-67. Details about the expedition to the Plains are from Norall unless otherwise noted

- ↑ Unrau, William E. The Kansa Indians: A History of the Wind People, 1673-1873. Norman: U of OK Press, 1971, p. 25

- ↑ Norall, 148

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird “Who Were the Padouca?”, American Anthropologist, Vol. 23, No. 3, June-Sept 1920, pp. 247-260

- 1 2 Norall, 151

- ↑ Norall, 160

- ↑ Norall, 160-161

- ↑ Reichart, Milton “Bourgmont’s Route to Central Kansas: A Reexamination.” Kansas History, Vol 2, Summer 1979, pp. 96-120