Dutch colonial rule of Taiwan

Dutch colonial rule lasted in Taiwan from 1642 to 1662.

An overview of life in Taiwan under Dutch rule

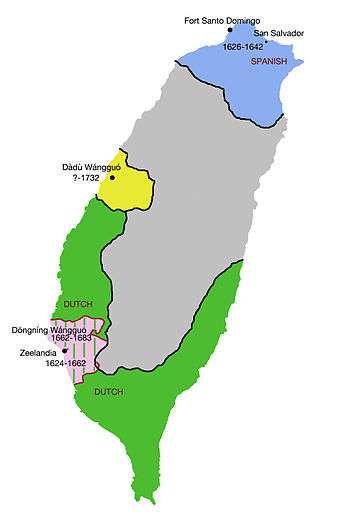

At the time of Dutch settlement in Taiwan, the northern part of the island was still occupied by Spanish who had landed there in 1626. However, they showed no signs of expanding their settlement and in 1642 the Dutch drove them out. As Tu Cheng-sheng states, there were three main reasons for the Dutch colonisation of Taiwan: “to ensure the security of the Philippines, to protect trade with China, and to prevent the Japanese from occupying the island”.[1]

Taiwan was in a perfect place strategically to engage in trade within the region. The Chinese had refused to allow the Dutch to settle on the Chinese territory of Penghu, and suggested they settle on Taiwan instead. The subsequent settlement of the island was reflective of the strategic value of Taiwan. The settlement was systematic and planned,[2] as the construction of the military stronghold of Castle Zeelandia demonstrated. The settlers were clearly aiming to protect their good position to engage in trade in the long-term, and to establish themselves as the administrators of Taiwan.

Administration of Taiwan

The Dutch approach towards the control and administration of Taiwan is best described as interventionist.[3] They were the first settlers who seriously sought to develop the island.[4] While the Dutch faced some initial opposition and hostility from indigenous tribes, they engaged in a number of expeditions to pacify them and eventually established peace that would last until their rule ended in 1662.[5]

Aboriginals were allowed to continue their lives relatively freely, but were required to make annual tribute to the Dutch in a manner similar to a feudal system.[3] In addition, the Dutch introduced a number of taxes, including export duties, sales tax and hunting taxes. They also laid down laws governing every aspect of life, including the organisation of markets, production of alcohol, construction of houses and observation of Sunday services.[3]

The process of converting indigenous peoples to Christianity also helped to increase the literacy of aboriginals, as clergymen sent by the Dutch East India Company were involved in translating the Bible from Dutch into Romanized versions of indigenous languages. The clergy were also involved in setting up schools, as well as serving as interpreters and tax collectors, playing a key role in the administration of Taiwan by the Dutch. This was largely due to the fact that they were heavily involved with the aboriginal tribes, and understood their cultures and the various dialects.

Trade

The Dutch presence in Taiwan also brought with it scientific and technological advances. The Dutch introduced well-digging,[6] as well as bringing both oxen and cattle to the island. In terms of the trade being engaged in, the settlers’ ultimate goal was to obtain the spices grown in Southeast Asia and sell them in Europe. To do this the Dutch exchanged Japanese and Chinese gold and silver for Indian cotton, which was then used to buy the spices. Those spices were eventually shipped back to Europe.

In 1622, the first Dutch fleet arrived in Penghu for trade with China. In the early 1620s, there was no trade due to the Sino-Dutch conflict over Penghu.[7] The trade resumed after the Dutch left Penghu and established their settlement in Taiwan in 1624.[7][8] After that, Taiwan became part of the Dutch trade network in Asia.[8] By exporting much sugar from Taiwan, the Dutch East India Company made a lot of profit from customs duties.[7] The Dutch imposed a 10 per cent custom duty on all imports and exports from Taiwan.[9]

However, between 1625 and 1628, the cessation of the trade resulted from Zheng Zhilong's attack on Chinese and Dutch shipping across the Taiwan Strait.[7] The trade resumed again after Zheng's surrender to Xiong Wen-zan in 1628.[7] Three ships sent from Taiwan to Japan and one to Java in 1628 carried 688,436 florins' worth of cargo.[7] After that the trade became more prosperous and ten years later, in 1637, fourteen Dutch ships carried cargoes estimated at 2,460,733 gulden 8 stuiver to Nagasaki in Japan.[7] In 1638, more cargo was exported from China to Taiwan and seven Dutch ships carried cargo estimated at 2,775,381 gulden to Japan during the monsoon period.[7]

Taiwan was one of the most important bases in Asia where the Dutch East India Company could make a lot of profit.[10] The Dutch could quickly gain a large profit from Taiwan as they used the labour of the Chinese immigrants largely from Fukien and the aborigines.[11] In 1649, its branches in Taiwan and Japan made a large profit while its nine other branches in Asia, including Siam and Ceylon, could not make any profit for the company.[10] The branch in Taiwan accounted for 26 per cent of the Company profit in that year and the branch in Japan accounted for 39 per cent.[10] In fact, the branch in Japan made much profit from the commodities imported from China via Taiwan.[10]

The company controlled the Asian market extending its trade over the whole of the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean.[10] Silk was exported from China to Japan and Europe and silver and copper from Japan to China by way of Taiwan. In this carrying trade, Taiwan was a significant base where not only produce camphor and sugar to export to Japan and Persia but also played a role of the relay station.[10] As trade increased, Taiwan, especially Taoyuan, became an important transshipment cetre for East Asian trade networks.[12] The products from Japan, Fukienn, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia were shipped to Taiwan, and then exported to other countries as the markets demanded.[12]

One of Taiwan's major export items was sulfur collected from near Keelung and Tamsui.[10] Another major export item was deer hides. In 1638, the Dutch exported 151,400 deer hides from Taiwan to Japan.[10] Although the amount of deer hides exported to Japan dropped due to the deer population decreased, the considerable amount of deer hides ranged from 50,000 to 80,000 was still exported.[10] Tea was also a major export item. After Chinese people settled in Taiwan, they started to grow tea on less fertile hilsides where rice could not be cultivated.[10]

Although sugar cane was a native crop of Taiwan, the indigenous people had never been able to make sugar granules from the raw sugar.[13] Chinese immigrants brought and introduce the technique to turn the raw sugar cane into sugar granules.[13] Sugar became the most important export item as the main purpose of producing sugar was to export it to other countries.[14] The sugar produced in Taiwan made far higher profit than the sugar produced in Java.[13] About 300,000 catties of sugar, which was one third of the total production, were carreid to Persia in 1645.[14] In 1658, Taiwan produced 1,730,000 catties of sugar and 800,000 catties of them were shipped to Persia and 600,000 catties to Japan.[14] The rest was exported to Batavia.[14]

The Dutch exported amber, spices, pepper, lead, tin, hemp, cotton, opium and kapok from Southeast Asia through Batavia to China by way of Taiwan and carried silk, porcelain, gold, and herbs from China to Japan and Europe via Taiwan.[11][14]

Clearly, Taiwan’s geographically advantageous position at the centre of all this trade in the region gave the Dutch a great advantage in playing a part in all of this trade.[15] However, in 1662 the Dutch were overwhelmed by Koxinga’s Chinese forces, who had moved into Taiwan to drive them out. And so Dutch rule in Taiwan ended, and the island became an important base for Koxinga over the following twenty years in his struggle against the Qing rule in mainland China.

Taxation

The rent for their farms also brought the Dutch a large profit. After the Dutch had got their control over Taiwan, they immediately levied a tax on all the import and export duties.[14] Although the rates of such taxation are unknown as there are no records, the Dutch must have made a lot of profit from the export duties received by Chinese and Japanese traders.[14] This resulted in the friction between the Dutch and the Japanese causing the Hamada Yahei incident in 1628.[9][14]

Another form of taxation was the poll tax which the Dutch levied on every person who was not Dutch and above six years of age.[14] At first, the rate of the poll tax was set at a quarter of a real whereas the Dutch, later on, increased the rate to a half real.[14] In 1644, the total amount of the poll tax imposed was 33,7000 reals and in 1644, over 70,000 reals were imposed.[14]

The Dutch imposed a tax on hunting as well. They sold a license to dig a pit-trap for 15 reals a month and a license for snaring was sold for one real.[14] During the hunting season between October 1638 and March 1639, the total amount of the hunt tax was 1,998.5 reals.[14] There were no licenses for fishing while it was taxed.[14]

By 1653, the Dutch revenue from Taiwan was estimated at 667,701 gulden 3 stuiver and 12 penning, including the revenue of 381,930 from tradings.[14] This indicates that for Dutch, taxation became the important way of making profit in Taiwan.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Tu Cheng-Sheng, (2003) Ilha Formosa: The Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, 32

- ↑ Tu Cheng-Sheng, (2003) Ilha Formosa: The Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, 30.

- 1 2 3 Tu Cheng-Sheng, (2003) Ilha Formosa: The Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, 31.

- ↑ Denny Roy, (2003) Taiwan: A Political History, Cornell University Press, New York, 15.

- ↑ Murray Rubinstein, (1999) A New History of Taiwan, M.E. Sharpe Inc, New York 63.

- ↑ Murray Rubinstein, (1999) A New History of Taiwan, M.E. Sharpe Inc, New York 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Huang, C 2011, 'Taiwan under the Dutch' in A new history of Taiwan, The Central News Agency, Taipei, p. 69

- 1 2 Tu, C 2003, 'The Deutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie' in Ilha Formosa: the emergence of Taiwan on the world scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, p. 23.

- 1 2 Lin, ACJ & Keating, JF 2008, 'The era of global navigation' in Island in the stream: a quick case study of Taiwan's complex history, SMC Publishing Inc., Taipei, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Huang, C 2011, 'Taiwan under the Dutch' in A new history of Taiwan, The Central News Agency, Taipei, p. 70.

- 1 2 Lin, ACJ & Keating, JF 2008, 'The era of global navigation' in Island in the stream: a quick case study of Taiwan's complex history, SMC Publishing Inc., Taipei, p. 8.

- 1 2 Tu, C 2003, 'The Deutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie' in Ilha Formosa: the emergence of Taiwan on the world scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Tu, C 2003, 'The Deutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie' in Ilha Formosa: the emergence of Taiwan on the world scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Huang, C 2011, 'Taiwan under the Dutch' in A new history of Taiwan, The Central News Agency, Taipei, p. 71.

- ↑ Tu Cheng-Sheng, (2003) Ilha Formosa: The Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century, Hwang Chao-sung, Taipei, 48.