Direct bonding

Direct bonding describes a wafer bonding process without any additional intermediate layers. The bonding process is based on chemical bonds between two surfaces of any material possible meeting numerous requirements.[1] These requirements are specified for the wafer surface as sufficiently clean, flat and smooth. Otherwise unbonded areas so called voids, i.e. interface bubbles, can occur.[2]

The procedural steps of the direct bonding process of wafers any surface is divided into

- wafer preprocessing,

- pre-bonding at room temperature and

- annealing at elevated temperatures.

Even though direct bonding as a wafer bonding technique is able to process nearly all materials, silicon is the most established material up to now. Therefore, the bonding process is also referred to as silicon direct bonding or silicon fusion bonding. The fields of application for silicon direct bonding are, e.g. manufacturing of Silicon on insulator (SOI) wafers, sensors and actuators.[3]

Overview

The silicon direct bonding is based on intermolecular interactions including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds and strong covalent bonds.[2] The initial procedure of direct bonding was characterized by a high process temperature. There is demand to lower the process temperature due to several factors, one is for instance the increasing number of utilized materials with different coefficients of thermal expansion. Hence, the aim is to achieve a stable and hermetic direct bond at a temperature below 450 °C. Therefore, processes for wafer surface activation i.e. plasma treatment or chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP), are being considered and are actively being researched.[4] The upper limit of 450 °C bases on the limitations of back-end CMOS processing and the beginning of interactions between the applied materials.[5]

History

The adhering effect of smooth and polished solid surfaces is first mentioned by Desaguliers (1734). His discovery was based on the friction between two surfaces of solids. The better the surfaces are polished the lower the friction is between those solids. This statement he described is only valid until a specific point. From this point on the friction starts to rise and the surfaces of the solids start to adhere together.[6] First reports of successful silicon direct bonding were published 1986 among others by J. B. Lasky.[7]

Conventional direct bonding

Scheme of a hydrophilic silicon surface |

Scheme of a hydrophobic silicon surface |

Direct bonding is mostly referred to as bonding with silicon. Therefore process techniques are divided in accordance with the chemical structure of the surface in hydrophilic (compare to scheme of a hydrophilic silicon surface) or hydrophobic (compare to scheme of a hydrophobic silicon surface).[6]

The surface state of a silicon wafer can be measured by the contact angle a drop of water forms. In the case of a hydrophilic surface the angle is small (< 5 °) based on the excellent wettability whereas a hydrophobic surface shows a contact angle larger than 90 °.

Bonding of hydrophilic silicon wafers

Wafer preprocessing

Before bonding two wafers, those two solids need to be free of impurities that can base on particle, organic and/or ionic contamination. To achieve the cleanliness without degrading the surface quality, the wafer passes a dry cleaning, e.g. plasma treatments or UV/ozone cleaning, or a wet chemical cleaning procedure.[2] The utilization of chemical solutions combines sequential steps. An established industrial standard procedure is SC (Standard Clean) purification by RCA. It consists of two solutions

- SC1 (NH4 OH (29%) + H2O2 (30%) + Deionized-H2O [1:1:5]) and

- SC2 (HCl (37%) + H2O2 (30%) + Deionized H2O [1:1:6]).

SC1 is used for removing organic contaminations and particles at a temperature of 70 °C to 80 °C for 5 to 10 min and SC2 is used for removing metal ions at 80 °C for 10 min.[9] Subsequently, the wafers are rinsed with or stored in deionized water. The actual procedure needs to be adapted to every application and device because of usually existing interconnects and metallization systems on the wafer.[10]

Pre-bonding at room temperature

Before contacting the wafers, those have to be aligned.[1] If the surfaces are sufficiently smooth, the wafers start to bond as soon as they get in atomic contact as shown in infrared photograph of a bond wave.

The wafers are covered with water molecules so the bonding happens between chemisorbed water molecules on the opposing wafer surfaces. In consequence a significant fraction of Si-OH (silanol) groups start to polymerize at room temperature forming Si-O-Si and water and a sufficient bonding strength for handling the wafer stack is assured. The formed water molecules will migrate or diffuse along the interface during annealing.[8]

After the pre-bonding in air, in a special gaseous atmosphere or vacuum, the wafers have to pass an annealing process for increasing the bonding strength. The annealing therefore provides a certain amount of thermal energy which forces more silanol groups to react among each other and new, highly stable chemical bindings are formed. The kind of binding which forms directly depends on the amount of energy which has been delivered or the applied temperature respectively. In consequence the bonding strength rises with increasing annealing temperatures.[2]

Annealing at elevated temperatures

Between room temperature and 110 °C the interface energy remains low, water molecules diffuse at the bond interface, leading to a rearrangement, causing more hydrogen-bonds. At temperatures from 110 °C to 150 °C silanol groups polymerize to siloxane and water, but also a slow fracture takes place. This reaction equates a thermo dynamical equilibrium and a higher density of silanol groups results in a higher number of siloxane and an increasing bond strength.

No further processes are observed at the interface between 150 °C and 800 °C until all OH-groups are polymerized and the composite strength remains constant.

Above 800 °C native oxide gets viscous and starts to flow at the interface, which increases the area of contacted surfaces. So, the diffusion of trapped hydrogen molecules along the interface is enhanced and interface voids may reduce in size or disappear at all. The annealing process is finished by the cooling of the wafer stack.[8]

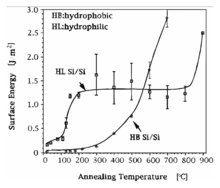

The interface energy increases to more than 2 J⁄m2 at 800 °C with a native oxide layer or at 1000 °C if the wafers are covered by thermal oxide (compare diagram of surface energy). In case one wafer contains a layer of thermal oxide and the other wafer is covered by a native oxide, the surface energy development is similar to a wafer pair both covered with a native oxide layer.[2]

Bonding of hydrophobic silicon wafers

Wafer preprocessing

A hydrophobic surface is generated if the native oxide layer is removed by either plasma treatment or by fluoride containing etching solutions, e.g. hydrogen fluoride (HF) or ammonium fluoride (NH4F). This process enhances the formation of Si-F bonds of the exposed silicon atoms. For hydrophobic bonding it is important to avoid re-hydrophilization, e.g. by rinsing and spin-drying, since Si-F bonds contacted with water result in Si-OH.[1]

Pre-bonding at room temperature

Prior to bonding the surface is covered with hydrogen and fluorine atoms. The bonding at room temperature is mostly based on van-der-Waals forces between those hydrogen and fluorine atoms. Compared to bonding with hydrophilic surfaces, the interface energy is lower directly after contacting. This fact builds up the need for a higher surface quality and cleanliness to prevent unbonded areas and thereby to achieve a full-surface contact between the wafers (compare infrared photograph of a bond wave).[1] Similar to bonding of hydrophilic surfaces, the pre-bond is followed by an annealing process.

Annealing at elevated temperatures

From room temperature to 150 °C no important interface reactions occur and the surface energy is stable. Between 150 °C and 300 °C more Si-F-H-Si bonds are formed. Above 300 °C the desorption of hydrogen and fluoride from the wafer surface leads to redundant hydrogen atoms that diffuse in the silicon crystal lattice or along interface. As a result, covalent Si-Si bonds start to establish between opposing surfaces. At 700 °C the transition to Si-Si bonds is completed.[11] The bonding energy reaches cohesive strengths of bulk silicon (compare diagram of surface energy).[2]

Low temperature direct bonding

Even though direct bonding is highly flexible in processing numerous materials, the mismatch of CTE (coefficient of thermal expansion) using different materials is a substantial restriction for wafer level bonding, especially the high annealing temperatures of direct bonding.[8]

The focus in research is put on hydrophilic silicon surfaces. The increase of the bonding energy is based on the conversion of silanol- (Si-OH) into siloxane-groups (Si-O-Si). The diffusion of water is mentioned as limiting factor because water has to be removed from the interface before close contact of surfaces is established. The difficulty is that water molecules may react with already formed siloxane-groups (Si-O-Si), so the overall energy of adhesion gets weaker.[2]

Lower temperatures are important for bonding pre-processed wafers or compound materials to avoid undesirable changes or decomposition. The reduction of the required annealing temperature can be achieved by different pretreatments such as:

- plasma activated bonding

- surface activated bonding

- ultra high vacuum (UHV)

- surface activation by chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP)

- surface treatment to achieve chemical activation in:

- hydrolyzed tetraalkoxysilanes Si(OR)4

- hydrolyzed tetramethoxysilane Si(OCH3)4

- nitride acid HNO3

Furthermore, research has shown that a lower annealing temperature for hydrophobic surfaces is possible with wafer pre-treatment based on:

- As+ implantation

- B2H6 or Ar plasma treatment

- Si sputter deposition

Examples

This technique is usable for the fabrication of multi wafer micro structures, i.e. accelerometers, micro valves and micro pumps.

Technical specifications

| Materials |

|

| Temperature |

|

| Advantages |

|

| Drawbacks |

|

| Research |

|

References

- 1 2 3 4 J. Bagdahn (2000). Festigkeit und Lebensdauer direkt gebondeter Siliziumwafer unter mechanischer Belastung (Thesis). Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A. Plössl and G. Kräuter (1999). "Wafer direct bonding: tailoring adhesion between brittle materials". Materials Science and Engineering. 25 (1-2). pp. 1–88.

- ↑ M. Wiemer and J. Frömel and T. Gessner (2003). "Trends der Technologieentwicklung im Bereich Waferbonden". In W. Dötzel. 6. Chemnitzer Fachtagung Mikromechanik & Mikroelektronik. 6. Technische Universität Chemnitz. pp. 178–188.

- ↑ D. Wünsch and M. Wiemer and M. Gabriel and T. Gessner (2010). "Low temperature wafer bonding for microsystems using dielectric barrer discharge". mst news. 1/10. pp. 24–25.

- ↑ P.R. Bandaru and S. Sahni and E. Yablonovitch and J. Liu and H.-J. Kim and Y.-H. Xie (2004). "Fabrication and characterization of low temperature (< 450 °C) grown p-Ge/n-Si photodetectors for silicon based photonics". Materials Science and Engineering. 113 (1). pp. 79–84.

- 1 2 S. Mack (1997). Eine vergleichende Untersuchung der physikalisch-chemischen Prozesse an der Grenzschicht direkt und anodischer verbundener Festkörper (Thesis). Jena, Germany: VDI Verlag / Max Planck Institute. ISBN 3-18-343602-7. horizontal tab character in

|title=at position 70 (help) - ↑ J. B. Lasky (1986). "Wafer bonding for silicon-on-insulator technologies". Applied Physical Letter. 48 (1). pp. 78–80.

- 1 2 3 4 Q.-Y. Tong and U. Gösele (1998). The Electrochemical Society, ed. Semiconductor Wafer Bonding: Science and Technology (1 ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-57481-1.

- ↑ G. Gerlach and W. Dötzel (2008). Ronald Pething, ed. Introduction to Microsystem Technology: A Guide for Students (Wiley Microsystem and Nanotechnology). Wiley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-470-05861-9.

- ↑ R. F. Wolffenbuttel and K. D. Wise (1994). "Low-temperature silicon wafer-to-wafer bonding using gold at eutectic temperature". Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 43 (1-3). pp. 223–229.

- ↑ Q.-Y. Tong and E. Schmidt and U. Gösele and M. Reiche (1994). "Hydrophobic silicon wafer bonding". Applied Physics Letters. 64 (5). pp. 625–627.