Derby Porcelain

The production of Derby porcelain dates from the first half of the 18th century, although the authorship and the exact start of the production remains today as a matter of conjecture. The oldest remaining pieces in the late 19th century bore only the words «Darby» and «Darbishire» and the years 1751-2-3 as proof of place and year of manufacture. More important is the fact that the production of porcelain in Derby predates the commencement of the works of William Duesbury, started in 1756 when he joined Andrew Planche and John Heath to create the Nottingham Road factory, which later became the Royal Crown Derby.[1][2]。

History

It is known by William Duesbury's own notes, that Derby had a solid production of exceptional quality porcelain in early 1750s. The proof of the quality of locally produced material is evidenced by the fact that Duesbury, then a known enameller in London, have paid considerably more for pieces manufactured in Derby than for figurines made by rival factories in Bow and Chelsea. It was common at the time that dealers purchased white glazed porcelain from various manufacturers, and send it to enamelists like Duesbury to do the final finishing (enamelling and colouring).[3]

The first printed mention about the Derby factory, however, dates only from December 1756, when an advertisement in the «Public Advertiser», republished several times throughout the month, urged readers to participate in a sale by auction in London, sponsored by the Derby Porcelain Manufactory. Curiously, there are no other references to this supposed «Derby Porcelain Manufactory,» which suggests that the name was specifically invented for the occasion.[4] Although it can be seen only as boasting, the advertisement calls the factory a «second Dresden,» showing the good quality of their products.[5] Of course, such perfection represented the culmination of a lengthy manufacturing process, and nothing in this announcement indicates that this annual sales had been the first of the factory, unlike what would occur with similar advertisements from manufacturers of Bow and Longton Hall in 1757.[6]

The potter Andrew Planche is often cited as a forerunner of the Derby china factory. Reports about a «foreigner in very poor circumstances» who lived in Lodge Lane and produced small porcelain figures around 1745, may refer to Planchè. However, as pointed out by a researcher, in 1745 Planchè was only 17 years old. The very importance of Planchè to the constitution of the future Royal Crown Derby was minimized by some (as the granddaughter of William Duesbury, Sarah Duesbury, who died in 1876), and contested by others, who doubt his existence. However, there is evidence that Planchè was really a historical figure, although he certainly has not taught the craft of enamelling to William Duesbury.[7]

A serious contender for the title of maker of the porcelain pieces of the «second Dresden» is the Cockpit Hill Potworks. We deduce that this «Derby Pot Works» was already in full operation around 1708, on behalf of a slipware tyg, containing the inscription John Meir made this cup 1708.[8] It is known that the «Pot Works» produced china, due to the announcement of an auction held in 1780, when the company went bankrupt. No mention is made of enamelled figures, but it is quite likely that they were also built, at a time when demand for these items was high. Or, perhaps, this branch of the works has been fully assimilated by the Duesbury's factory from the second half of 1750s on.[9]

Because of an arrest warrant drawn up in 1758 against a certain John Lovegrove, we know that the owners of the «Cockpit Hill Potworks» were William Butts, Thomas Rivett and John Heath. Heath was the banker who later would finance the construction of the Nottingham Road factory, and Rivett was Member of Parliament and Mayor of Derby in 1761, where one finds that Potworks' partners were wealthy and influential men in local society. However, competition with the Nottingham Road factory seems to have been fatal. Already in 1772, the quality of Potworks' production had fallen to the point where a visitor does classify it as «imitation of the Queen's ware, but it does not come up to the original, the produce of Staffordshire.»[10] In 1785, the factory closed its doors permanently.[11]

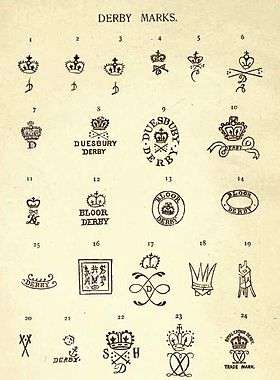

Derby porcelain marks

From the book Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain by William Bemrose (1898):

- 1, 2, 3 - Earliest Derby Marks, generally in blue (some examples are known where the Crown and D are used separately, probably an oversight by the workmen).

- 4 - Crossed swords, crown, and D, and 6 dots, carefully painted in blue, later in puce, used from about 1782.

- 5, 6 - Ditto, less carefully painted in red.

- 7, 8, 9, 10 - Later Duesbury Marks, generally in red.

- 11 - Duesbury & Kean, seldom used, circa 1795 to 1809.

- 12, 13, 14, 15 - Bloor Marks, commence 1811 to 1849.

- 16, 17, 18, 19 - Quasi Oriental Marks used on several occasions in matching, and to use up seconds stock by Bloor. No. 17 is an imitation of the Sèvres mark.

- 20 - Dresden Mark, often used on figures.

- 21 - Derby Mark, supposed to have been used by Holdship when at Derby, about 1766. Rare.

- 22 - Stephenson & Hancock, King Street Factory, 1862, same mark used afterwards by Sampson Hancock, and now in use, 1897.

- 23 - Mark used by the Derby Crown Porcelain Co., Osmaston Road, from its establishment in 1877 to Dec., 1889.

- 24 - This Mark adopted by the above Co. when Her Majesty granted the use of the prefix "Royal" on 3 January 1890.

References

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. pp. vi.

- ↑ Olga Baird. "Derby Porcelain in the 18th and early 19th centuries". The Revolutionary Players. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. p. 7.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. pp. 100–101.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Dresden Dinnerware". Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. p. 99.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. p. 101.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. p. 101.

- ↑ Bemrose, William (1898). Bow, Chelsea, and Derby Porcelain. London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd. p. 168.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Derby Porcelain. |

- "History of Royal Crown Derby Porcelain Co.". History of UK Potters and Potteries 1900-2010. Retrieved 2010-07-16.