Convention on the Continental Shelf

| |

| Signed | 29 April 1958 |

|---|---|

| Location | Geneva, Switzerland |

| Effective | 10 June 1964 |

| Signatories | 43 |

| Parties | 58 |

| Languages | Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish |

|

| |

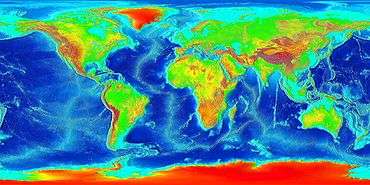

The Convention on the Continental Shelf was an international treaty created to codify the rules of international law relating to continental shelves. The treaty, after entering into force 10 June 1964, established the rights of a sovereign state over the continental shelf surrounding it, if there be any. The treaty was one of three agreed upon at the first United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS I).[1] It has since been superseded by a new agreement reached in 1982 at UNCLOS III.

The treaty dealt with seven topics: the regime governing the superjacent waters and airspace; laying or maintenance of submarine cables or pipelines; the regime governing navigation, fishing, scientific research and the coastal state's competence in these areas; delimitation; tunneling.[2]

Historical background

The Convention on the Continental Shelf replaced the earlier practice of nations having sovereignty over only a very narrow strip of the sea surrounding them, with anything beyond that strip considered International Waters.[3] This policy was used until President of the United States Harry S Truman proclaimed that the resources on the continental shelf contiguous to the United States belonged to the United States through an Executive Order on 28 September 1945.[4] Many other nations quickly adapted similar policies, most stating that their portion of the sea extended either 12 or 200 nautical miles from its coast.

Rights of states

Article 1 of the convention defined the term shelf in terms of exploitability rather than relying upon the geological definition. It defined a shelf "to the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas adjacent to the coast but outside the area of the territorial sea, to a depth of 200 meters or, beyond that limit, to where the depth of the superjacent waters admits of the exploitation of the natural resources of the said areas" or "to the seabed and subsoil of similar submarine areas adjacent to the coasts of islands".[5]

Besides outlining what is legal in continental shelf areas, it also dictated what could not be done in Article 5.[6]

Participants

| Country | Ratification Year | Country | Ratification Year |

| Albania | 1964 | Mauritius | 1970 |

| Australia | 1963 | Mexico | 1966 |

| Belarus | 1961 | Netherlands | 1966 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1994 | New Zealand | 1965 |

| Bulgaria | 1962 | Nigeria | 1961 |

| Cambodia | 1960 | Norway | 1971 |

| Canada | 1970 | Poland | 1962 |

| Colombia | 1960 | Portugal | 1963 |

| Costa Rica | 1972 | Romania | 1961 |

| Croatia | 1992 | Russian Federation | 1960 |

| Cyprus | 1974 | Senegal | 1961 |

| Czech Republic | 1993 | Sierra Leone | 1966 |

| Denmark | 1963 | Slovakia | 1993 |

| Dominican Republic | 1964 | Solomon Islands | 1981 |

| Fiji | 1971 | South Africa | 1963 |

| Finland | 1965 | Spain | 1971 |

| France | 1965 | Swaziland | 1970 |

| Greece | 1972 | Sweden | 1966 |

| Guatemala | 1961 | Switzerland | 1966 |

| Haiti | 1960 | Thailand | 1968 |

| Israel | 1961 | Tonga | 1971 |

| Jamaica | 1965 | Trinidad and Tobago | 1968 |

| Kenya | 1969 | Uganda | 1964 |

| Latvia | 1992 | Ukraine | 1961 |

| Lesotho | 1973 | United Kingdom | 1964 |

| Madagascar | 1962 | United States | 1961 |

| Malawi | 1965 | Venezuela | 1961 |

| Malaysia | 1960 | Yugoslavia | 1966 |

| Malta | 1966 | ||

UNCLOS II and III

In 1960, the United Nations held another conference regarding the Laws of the Sea, UNCLOS II, but no agreements were reached. However, another conference was called in 1973 to address the issues. UNCLOS III, which lasted until 1982 due to a required consensus, adjusted and redefined many principles stated in the first UNCLOS. The new definition of the Continental shelf in the new Convention rendered the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf obsolete. The principal reason for this was technological advancements.[8]

References

- ↑ Text of the UN treaty

- ↑ Dupuy, René Jean; Daniel Vignes (1991). A Handbook on the New Law of the Sea. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-7923-0924-6.

- ↑ http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/policy/1945/450928a.html

- ↑ Shaw, Malcolm Nathan (2003). International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-521-82473-6.

- ↑ Text of the treaty from WikiSource

- ↑ http://www.intfish.net/igifl/treaties/multilateral/geneva-continental.htm

- ↑ "United Nations: UN Studies Ocean-Bed Treaty". Facts on File News Services. 27 November 1968. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

External links

- Ratifications, at depositary

- Anna Cavnar, Accountability and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf: Deciding Who Owns the Ocean Floor