Clavicytherium

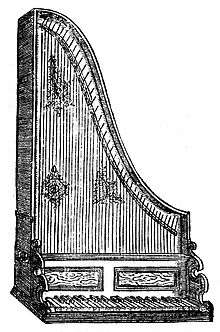

A clavicytherium is a harpsichord in which the soundboard and strings are mounted vertically facing the player. The primary purpose of making a harpsichord vertical is the same as in the later upright piano, namely to save floor space. In a clavicytherium, the jacks move horizontally without the assistance of gravity, so that clavicytherium actions are more complex than those of other harpsichords.

Design

In any harpsichord, the strings are plucked by small plectra, held by jacks, which are thin strips of wood. In a standard harpsichord, the strings are placed horizontally and the jacks are vertical. Thus to make the jack return to position (after it has been lifted by a key to pluck) is a simple matter of gravity; with proper adjustment the jack will simply fall back into its rest position (for details and diagrams see Harpsichord).

A clavicytherium sacrifices this simplicity and must find some other means to make the jacks return. In some instruments, this is accomplished with a spring. Another possibility is to couple the jack mechanically to other portions of the action (e.g. keys, levers) that do return by gravity, pulling the jacks back with them.[1] Inevitably, neither strategy is as simple as the direct vertical drop of the jacks in a standard harpsichord. Indeed, finding a good design for a clavicytherium action is not easy, and builders repeatedly sought better solutions. Van der Meer writes, "no standard was ever devised, and there are nearly as many variations of it as there are instruments in existence."[2] Many designs were rather unsuccessful: Ripin reports that clavicytheria often have "a fairly heavy touch and unresponsive action".[3] Describing the unusually fine clavicytheria of Delin (see below), Kottick observes "the action feels quite good to the fingers, which is not a statement one can always make about a clavicytherium."[4]

A special property of clavicytheria is that the player is seated directly in front of the soundboard, at close range. Kottick notes, "[in] all clavicytheria, close proximity to the soundboard provides the player with an overwhelming sense of sonic immersion."[5] Indeed, the modern builder William Horn suggests that it is this esthetic end, not space-saving, that is the primary justification for making clavicytheria.[6]

In shape, clavicytheria were normally like ordinary harpsichords, with the left side longer than the right to accommodate the long bass strings. Occasionally, symmetrical clavicytheria were made, with two bentsides and the peak in the middle; this is sometimes called a "pyramid" shape. The pyramidal design was a challenge to builders, as Ripin notes: "Difficulties arise, since the longer bass strings are in the middle and the treble strings are at the sides, and system of intermediate levels (rollerboard) is required to permit each key to play the correct string unless diagonal stringing is used."[7]

Except in the early period of their construction, clavicytheria were tall. William Horn warns potential buyers that they will need 280 cm. of room below their ceilings (nine feet two inches) to accommodate his Delin replica.[8] The Instrument Workshop, offering plans for a Delin-based instrument, actually reduces its height to 262 cm. (eight feet seven inches) in order to "adapt Delin’s design to modern interiors".[9]

The RCM clavicytherium

The earliest harpsichord known, dating from about 1470, is a clavicytherium. It may have been built in Ulm, and currently resides in the musical instrument collection of the Royal College of Music in London. It is a fairly small instrument (about four feet eight inches tall[10]) with a short compass, just 41 notes. The apex forms a sharp edge, as there is no tailpiece. Kottick observes that the RCM instrument closely resembles another (unpreserved) clavicytherium found as a diagram in the work of Henri Arnaut de Zwolle.[11]

Ripin describes its "unique and simple action" thus: "the key, a vertical lever and the forward-projecting jack are all assembled into a single rigid piece. When the key is depressed the entire assembly rocks forward so that the jack (moving along the path of an arc) is forced past its string; when the key is released, the assembly falls back again under its own weight, returning the jack to its original position."[12]

Kottick remarks that "the RCM clavicytherium is a refined and sophisticated instrument, which suggests that it represents a mature tradition".[13] Indeed, since the harpsichord was probably invented before 1400,[14] the RCM instrument probably reflects several decades of development.

Later clavicytheria

Clavicytheria are mentioned in Sebastian Virdung's 1511 work Musica Getutscht, the first surviving reference work on music; Virdung calls the instrument clauiciterium.[15] They are also mentioned in the Syntagma Musicum (1614-1620) of Michael Praetorius, the Harmonie universelle (1637) of Marin Mersenne, and in the French Encyclopédie méthodique.[16] Bartolomeo Cristofori, who invented the piano, built clavicytheria, of which one may actually survive.[17]

In the 18th century particularly fine clavicytheria were made by Albert Delin (1712–1771), a Flemish builder who worked in Tournai.[18] Chung describes his work thus: "[he] succeeded in overcoming the difficulties of building an upright harpsichord better than any other builder. His three instruments, which are considered by many to be the finest of all surviving clavicytheria, have an amazingly fine touch that is achieved by a special action that upon the release of the keys allows the jacks to return without the need of springs or additional weights."[19]

The city of Dublin also apparently enjoyed a vogue in the 18th century for clavicytheria, and quality instruments were made by a number of builders. Instruments survive today built by Ferdinand Weber (1715-1784), Henry Rother (f. 1762-1774), and Robert Woffington (d. 1823). The instruments by Rother and Weber are pyramidal.[20]

The clavicytherium became temporarily extinct along with the horizontal harpsichord around the end of the 18th century. The 20th-century revival of the harpsichord has seen the construction of a small number of new instruments; Kottick, writing of the revival as of 1987, said "The clavicytherium does not seem to have caught on much at all", though a few modern builders, noted above, have constructed them.[21]

Nomenclature

Keyboard instrument scholar A. J. Hipkins attributed the name "clavicytherium" to Virdung. It is a Latino-Greek compound, from Latin clavis 'key' and Greek cythara; the latter denoted a variety of stringed instruments.[22]

In other languages the instrument is called clavecin verticale (French), Klaviziterium (German), cembalo verticale (Italian).

References

- ↑ Hubbard 2002:294

- ↑ van der Meer (1978:247)

- ↑ Ripin 1989, 180

- ↑ Kottick 2002:294

- ↑ Kottick 2002:294

- ↑ Source: Horn web site: http://www.williamhorn.it/clavicembali/en/catalogue/clavicytherium

- ↑ Ripin 1989, 180

- ↑ Source: Horn web site, cited above

- ↑ Source: the firm's website at http://www.fortepiano.com/plans_files/clavicytherium.htm

- ↑ Ripin (1989:180); more precisely: "142.5 cm., including a stand of 6.9 cm."

- ↑ Kottick (2002:25)

- ↑ Ripin (1989:180)

- ↑ Kottick 2003:25

- ↑ Perhaps by Hermann Poll; Kottick (2003:10)

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, online edition, entry "Clavicytherium".

- ↑ Hubbard 1967, 77

- ↑ It is in the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Rome; Kottick (2002:500) considers the attribution to Cristofori to be "probable".

- ↑ Hubbard 1967, 77; Chung 2005

- ↑ Chung 2005

- ↑ Kottick (2002:381-382)

- ↑ Kottick (1987)

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, online edition, entry "Clavicytherium".

Sources

- Chung, David. 2005. Review of Jean-Henry D’Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin (Paris, 1689). Hank Knox, clavicytherium. Les Productions Early-music.com, 2003. Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 11.1.

- Hubbard, Frank (1967) Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Kottick, Edward (1987) The Harpsichord Owner's Guide: A Manual for Buyers and Owners. UNC Press Books.

- Kottick, Edward (2002) A History of the Harpsichord. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Ripin, Edwin M. (1989) Early Keyboard Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.