Mourning Dove (author)

| Mourning Dove[1][note 1] | |

|---|---|

| Hum-ishu-ma[1] | |

|

Mourning Dove, c. 1915 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1884[1] near Bonners Ferry, Idaho |

| Died |

8 August 1936[1] Medical Lake, Washington |

| Cause of death | flu[1] |

| Resting place | Omak Memorial Cemetery, WA[1] |

| Spouse(s) |

Hector McLeod (Flathead people)[2] Fred Galler (Wenatchee people)[1] |

| Parents |

Joseph Quintasket (father)[1] Lucy Stukin (mother)[1] |

| Known for |

Writing books: |

| Nickname(s) | Christal Quintasket (her English name)[1] |

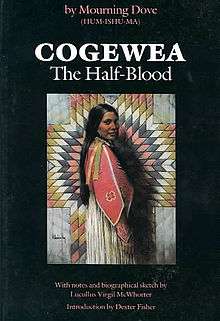

Mourning Dove or Christal Quintasket (Okanogan) was a Native American author in the United States best known for her 1927 novel Cogewea, the Half-Blood: A Depiction of the Great Montana Cattle Range and her 1933 work Coyote Stories.

Cogewea was one of the first novels to be written by a Native American woman and to feature a female protagonist. Cogewea explores the lives of Cogewea, a mixed-blood hero whose ranching skills, riding prowess, and bravery are noted and greatly respected by (the primarily mixed-race) cowboys on the ranch on the Flathead Indian Reservation, more appropriately known as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation.The eponymous main character hires a greenhorn easterner, Alfred Densmore, who has designs on Cogewea's land (land allotted as per the Dawes Act).

Coyote Stories (1933) is a collection of what she called Native American Folklore.[4]

Her name

She was born Christal Quintasket in 1888.[2] Quintasket was a surname her father had taken from his stepfather.[5] She also was given a native name, Hum-Ishu-Ma. Early in her life, Quintasket was forced to give up her language while attending the Sacred Heart School at the Goodwin Mission in Ward, near Kettle Falls, Washington. She forgot the meaning of her native name.[5] She thought it meant Mourning Dove.[2]

But she later said, “the whiteman must have invented the name for it”, after realizing that her people did not give women animal or bird names.[2] She also realized that she at first spelled it incorrectly in English, believing it was Morning Dove. After seeing a labeled mourning dove in a museum, she realized the error and changed it to 'Mourning Dove.[2][6]

Background

Hum-Ishu-Ma (Mourning Dove) (Christal Quintasket) was born "in the Moon of Leaves" (April) 1888 in a canoe on the Kootenai River near Bonners Ferry, Idaho.[5][7] Her mother Lucy Stukin was of Sinixt (Lakes) and Colville (Skoyelpi) ancestry.[8] Lucy was the daughter of Sinixt Chief Seewhelken and her mother was Colville.[5] Christal spent much time with her maternal grandmother, learning storytelling from her. Christal's father was Joseph Quintasket, a mixed-race Okanagan.[5] His mother Nicola was Okanagan[8] and his father was Irish. He grew up with his mother and stepfather.[5] While living at the Colville Reservation, Christal Quintasket was enrolled as Sinixt (Lakes), but she identified as Okanogan.[8] The tribes shared related languages and some culture.

Hum-Ishu-Ma learned English in school. After reading The Brand: A Tale of the Flathead Reservation by Theresa Broderick, she was inspired to begin writing.[5] Her command of English made her valued by her fellow natives and she advised local Native leaders.[5] She also became active in Native politics, for instance getting money paid that was owed to her tribe.[5]

Personal life

She married Hector McLeod, a member of the Flathead people, who proved to be an abusive husband.[5] After they separated, in 1919 she married Fred Galler of the Wenatchi.[5][9]

She died on 8 August 1936 at the state hospital at Medical Lake, Washington.[5]

Cogewea, the Half-Blood

Mourning Dove's 1927 novel explores a theme common in early Native American fiction: the plight of the mixedblood (or "breed"), who lives in both white and Indian cultures. Typically mixed-race Native Americans had Indian mothers and white fathers, beginning with fur traders and trappers, and later other explorers. There were strong alliances created between tribes and traders in the marriage of their daughters to Europeans.

The Okanogan mother of Cogewea and her sisters Julia and Mary dies. Their white father leaves them for the promise of the Alaskan gold rush, joining tens of thousands of men to migrate there. Their maternal grandmother Stemteemä raises the girls as Okanogan. After Julia marries a white man, she takes in her younger sisters at his ranch located within the boundaries of the Flathead Indian Reservation. Cogewea is soon courted by Alfred Densmore, a white suitor from the East Coast (United States), and James LaGrinder, the ranch foreman who is mixed race. (The sisters split on their views of these men: Julia approves of Densmore but Mary is suspicious of him.) Cogewea and Jim reach a happy ending. The novel is important as an early work by a Native American woman and as one that has a happy ending for the mixed bloods.

Mourning Dove collaborated on this work with her editor Lucullus Virgil McWhorter.A new author, Mourning Dove felt that her editor McWhorter greatly changed her book; she wrote to him that he had added elements that made her feel the book was no longer hers:

"I have just got through going over the book Cogewea, and am surprised at the changes that you made. I think they are fine, and you made a tasty dressing like a cook would do with a fine meal. I sure was interested in the book, and hubby read it over and also all the rest of the family neglected their housework till they read it cover to cover. I felt like it was some one else's book and not mine at all. In fact the finishing touches are put there by you, and I have never seen it".[10]

Mourning Dove agreed to the changes, later writing to him: "My book of Cogewea would never have been anything but the cheap foolscap paper that it was written on if you had not helped me get it in shape. I can never repay you back."[2]

This novel is one of the earliest written by a Native American woman and published in the United States. It followed Wynema, a Child of the Forest (1891) by Sophia Alice Callahan (Creek), which was rediscovered in the late 20th century and published in 1997 in a scholarly edition. Mourning Dove's work was one of the earliest to feature a female protagonist.

Mourning Dove's self proclaimed great-niece, Jeannette Armstrong published Slash (1985), the first novel by a First Nations woman in Canada.[11]

Cogewea was reprinted in 1981 in a scholarly edition by the University of Nebraska Press.

Coyote Stories

In 1933, Mourning Dove published Coyote Stories, a collection of legends told to her by her grandmother and other tribal elders.

The foreword by Chief Standing Bear in this book includes these words by him: "These legends are of America, as are its mountains, rivers, and forests, and as are its people. They belong!"

Literary influences

Mourning Dove learned storytelling from her maternal grandmother, and from Teequalt, a grandmotherly lady who lived with her family when she was young.[5] She was also influenced by pulp-fiction novels, which her adopted brother Jimmy Ryan let her read.[5] She cited the novel The Brand: A Tale of the Flathead Reservation by Therese Broderick as inspiring her to begin writing, mainly because she wanted to counter the derogatory representation of indigeneity in Broderick`s novel.[5]

Works

- In Spanish as: Cuentos Indios del Coyote, Paloma Triste (Mourning Dove)

- Shorter (17 stories) English version as: Mourning Dove's Stories[note 2] (117 pages) (1991)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hum-ishu-ma (Mourning Dove – not a direct translation), as provided by Mourning Dove herself in her introduction to Cogewea: "The whiteman must have invented the name for it as Mourning Dove because the translation to Indian is not word for word at all." Okanogan women names refer to water, not birds or animals.

- ↑ The 17 stories are:

- "Ant"

- "Rivals last stand"

- "Legend of Omak lake"

- "Lynx and wife"

- "Lynx the hunter"

- "One who follows"

- "How disease came to the people"

- "Coyote the medicine man"

- "Coyote's daughter"

- "Coyote and fox"

- "Blind dog monster"

- "Coyote is punished"

- "Wooing grizzly bear"

- "Coyote and whale monster"

- "North wind monster"

- "Coyote brings the salmon"

- "Salmon and rattlesnake"

- "Ant"

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 John Brent Musgrave. "Mourning Dove: Chronicler and Champion of the Okanagan People". Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Arloa. "Mourning Dove, (Christal Quintasket)". Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Carol Miller. "Mourning Dove (Christine Quintasket)". Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ↑ See Dexter Fisher's introduction to the University of Nebraska edition of Cogewea, p. viii.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 ABC Book World. "Dove, Mourning". Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ↑ Lucullus Virgil McWhorter. "The Discards". Gutenberg Project. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ↑ Mourning Dove, Coyote Stories, University of Nebraska Press, 1990, p10

- 1 2 3 Brown, Alanna K. "Mourning Dove" in Andrew Wiget's Dictionary of Native American Literature, 1994, ISBN 0-8153-1560-0, p145

- ↑ Marshall, Maureen E. Wenatchee's Dark Past. Wenatchee, Wash: The Wenatchee World, 2008.

- ↑ Lutz, Hartmut, ed. Interview with Jeannette Armstrong. Contemporary Challenges: Conversations with Canadian Native Authors. Saskatoon: Fifth House, 1991. 13

Further reading

- Bataille, Gretchen M., Native American Women: a Biographical Dictionary, pp. 178-179.

- Bloom, Harold, Native American Women Writers, pp. 69-82.

- Buck, Claire, The Bloomsbury Guide to Women's Literature, p. 838.

- Witales, Janet, et al., Native North American Literary Companion.

External links

- "Mourning Dove", HistoryLink, biography and several photographs of the writer

- "Mourning Dove", Native American Author's Project, Internet Public Library

- Bibliography of scholarship on Mourning Dove

- "Empowering Indigenous Women through Literature and Publishing", Cogewea blog, includes history of publication and photo

- Biography online.

- Therese Broderick, The Brand: Tale of the Flathead Reservation, (Seattle: Alice Harriman Company, 1909), novel available free online