Chinese Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area

| Part of a series on |

| Ethnicity in Toronto |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The Chinese Canadian community in the Greater Toronto Area was first established around 1877, with an initial population of two laundry owners. While the Chinese population was initially small in size, it dramatically grew beginning in the 1960s due to changes in immigration law and political issues in Hong Kong. Additional immigration from Southeast Asia in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and related conflicts and a late 20th century wave of Hong Kong immigration further established the Chinese in Toronto. The Chinese established many large shopping centres in suburban areas catering to their ethnic group.

History

In 1877 the first Chinese persons had been recorded in the Toronto city directory; Sam Ching and Wo Kee were laundry business owners. Additional Chinese laundries opened in the next several years.[1] Toronto's earliest Chinese immigrants originated from rural communities of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong, such as Taishan and Siyi,[2] and they had often arrived in the west coast of Canada before coming to Toronto. Many of them worked in small businesses, as merchants, and in working class jobs.[3]

100 Chinese persons lived in Toronto in 1885.[4] The Chinese initially settled the York-Wellington area as Jews and other ethnic groups were moving out of that area. Several Toronto newspapers in the early 20th century expressed anti-Chinese sentiment through their editorials.[5] 1,000 Chinese lived in Toronto by 1911.[4] In 1910 redevelopment of York-Wellington forced many Chinese to relocate from that area, with many going to the portion of Queen between Elizabeth and York.[6] less than ten years later redevelopment occurred again and the Chinese were again forced to move, with the main destination being former Jewish housing on Elizabeth Street; this area became the Toronto Chinatown and stabilized. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 stopped Chinese immigration inflow into Toronto, causing a decline in residents and businesses in the community.[7] The Great Depression augmented the decline in the Chinatown.[8]

By the 1950s and 1960s ethnic Chinese who had English fluency continued to do ethnic shopping in Chinatown but began living in suburban areas. In addition many ethnic Chinese began studying in Toronto-area universities during those decades. Educated, English-fluent Chinese people came to Toronto after the Canadian government adopted point system criteria for immigration selection purposes in 1967; many of them worked skilled jobs and/or were well-educated.[9] Many Hong Kongers arrived during the late 1960s and early 1970s due to the new points system and because of the Hong Kong 1967 Leftist riots.[10] Bernard H. K. Luk, author of "The Chinese Communities of Toronto: Their Languages and Mass Media," stated that until the 1970s the Toronto area pan-Chinese community "was small".[11]

Vietnamese Chinese were among the people fleeing Vietnam after the Fall of Saigon in 1975. Many of them did not speak Vietnamese.[12] In general most ethnic Chinese originating from Southeast Asia were refugees.[13]

Around 1980 Toronto's ethnic Chinese population became the largest in Canada. Until then, Vancouver had the largest ethnic Chinese population in Canada.[14] Many Hong Kongers immigrated to Toronto in the 1980s and 1990s, partly because of the impending 1997 Handover of Hong Kong; Canada had resumed allowing independent immigrants into the country in 1985 after a temporary suspension that began in 1982. The Chinese population of the Toronto area doubled between 1986 and 1991.[15] Many of the new arrivals went to North York and Scarborough in then-Metropolitan Toronto and in Markham and Richmond Hill in York Region.[16] The estimated total number of Hong Kongers who immigrated to the Toronto area from the 1960s to the 1990s was fewer than 200,000.[10] A total of 360,000 immigrants from China, most of them originating from Hong Kong, settled in the GTA in a period around 1979 through 1999.[13]

Vivienne Poy wrote that by 1990 there were fears of ethnic Chinese expressed in Toronto area media.[17] In 1991 there were 240,000 ethnic Chinese in the Toronto area.[15]

In 2000 Toronto continued to have the largest Chinese population in Canada.[4]

Geographic distribution

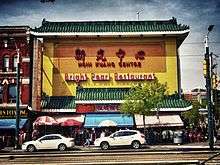

Chinese communities include Chinatown, Toronto.

According to The Path of Growth for Chinese Christian Churches in Canada by Chadwin Mak, as of 1994 there were about 100,000 ethnic Chinese in Scarborough, 65,000 in Downtown Toronto, 60,000 in East Toronto, 40,000 in North York, and 10,000 in Etobicoke/Downsview. In addition, there were 35,000 in Thornhill/Markham, 30,000 in Oakville/Mississauga, 5,000 in Brampton, 2,000 in Oshawa, and 1,500 in Pickering. The total of Metropolitan Toronto and the other regions combined was 348,500.[18]

By 2012 Markham and Richmond Hill had absorbed many Chinese immigrants.[19]

Demographics

Chinese immigrants include those who immigrated from Hong Kong, Mainland China and Taiwan.[13] Southeast Asia-origin Chinese in Toronto originated from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Other ethnic Chinese immigrants originated from the Caribbean, Korea, South Africa, and South America.[4]

As of 2000 there were an estimated fewer than 50,000 ethnic Chinese Vietnamese Canadians living in the Toronto area, making up almost half of the metropolitan area's total number of Vietnamese Canadians.[10]

Institutions

There were 105 associations and 25 social service agencies that were listed in the 1997 Chinese Consumer Directory of Toronto.[20] Bernard Luk wrote that some agencies may not have advertised, so the directory was "not exhaustive".[11] In Toronto usually Chinese Vietnamese formed communities organizations separate from those of the Kinh people.[12]

Individual organizations

The Chinese Benevolent Association (CBA) mediated between the Chinese community and the Toronto city government and within the Chinese community, and it stated that it represented the entire Chinese community. The CBA, which had its headquarters at the intersection of Elizabeth Street and Hagerman Street, was originally created in regards to Chinese political developments during the late Qing Dynasty.[21] In much of its history it was allied to the Kuomintang.[22]

The Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC) is a Chinese Canadian rights organization that, as of 1991, had 29 affiliates and chapters throughout Canada. It was formed in 1979.[23]

As of 1991 the Chinese Cultural Centre of Greater Toronto (CCC) had 130 members and organizes cultural activities such as dragon boat races, musical concerts, and ping pong tournaments. The steering committee of the CCC was established in the summer of 1988.[24]

The Hong Kong-Canada Business Association (HKCBA) is a pro-Hong Kong-Canada trade, investment, and bilateral contact organization. Its Toronto section, as of 1991, had about 600 members and it had more than 2,900 members in ten other Canadian cities. The organization published a newsletter, The Hong Kong Monitor, distributed throughout Canada. Each section also had its own bulletin. The HKCBA was established in 1984.[23]

The Si Ho Tong was one of the family name-based mutual aid organizations active in the 1930s.[21]

The Toronto Association for Democracy in China (TADC) is a 1989 movement organization and human rights organization. In 1991 it had 200 members. It was established on May 20, 1989 as the Toronto Committee of Concerned Chinese Canadians Supporting the Democracy Movement in China, and in April 1990 was incorporated in Ontario as a nonprofit organization.[23]

The Toronto Chinese Business Association, which represents ethnic Chinese businesspersons in the Toronto area, had about 1,100 members in 1991. It was founded in 1972. This organization is a sister association of the Ontario Chinese Restaurant Association.[24]

Politics

The Chinese Benevolent Association gained power after several factions competed for political dominance in the 1920s: the political consolidation was completed by the 1930s.[25] Many clan organizations and family name organizations, or tong,[2] formed political backbone of the Chinese community in the 1930s and 1940s. The Toronto political establishment referred to a "Mayor of Chinatown," an informal office that served as a liaison between the city's power structure and the Chinese hierarchy. The Chinese persons communicating with the white community were at the top of the ethnic Chinese social and political hierarchy and made themselves as the representatives of the entire Chinese community.[26] The tong and hui geographical and surname groups were under the political control of the CBA, and dues paid to these umbrella organizations rose to the top of the CBA leadership.[25]

The end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and the Communist Party of China rule in the Mainland caused political fissures in the Chinese community.[25] Organizations which were pro-CPC left the CBA-oriented power structure.[27] The CBA lost its political dominance by the 1960s.[25]

Language

Varieties of Chinese

Different subgroups of Chinese people in Toronto speak different varieties of Chinese, and differences in language between these subgroups differentiates and demarcates them.[28] The original Chinese immigrants to Toronto who originated from the Siyi area of Guangdong province spoke the Siyi dialects of Yue Chinese,[29] as well as the Taishanese dialect of Yue;[27] as of 2000 many speakers of the Siyi dialects, including the immigrants and their children, lived in the Toronto Chinatown.[29] As of 2000 the Chinese variety with the largest representation was Metropolitan Cantonese, due to the two major waves of Hong Kong immigration in the 20th century that made Hong Kong Chinese the largest subgroup in Toronto.[10] In the 1990s there were speakers of Cantonese Chinese in the traditional Toronto Chinatown; and also in Agincourt, Willowdale, and other northern areas in Toronto, as well as Markham and Richmond Hill.[30]

Mandarin Chinese gained a significant presence due to immigration from Mainland China and Taiwan;[10] In the 1990s, some Mandarin speakers from the Mainland and/or speakers of northern Chinese dialects lived in the Toronto Chinatown, Richmond Hill, and Markham. Mandarin speakers from Mainland China and Taiwan lived in Willowdale and other parts of northern Toronto.[30] In the 1950s, before large scale Mandarin-speaker immigration occurred, the Toronto Chinese community used Mandarin on an occasional basis.[27]

Other varieties of Chinese, including Hakka, Hokkien, and Min Nan are spoken by ethnic Chinese from various countries.[10] Willowdale and other areas of Northern Toronto had speakers of Taiwanese Min Nan, and speakers of other Chinese varieties lived in other communities in the Toronto area, including Downsview in Toronto and Mississauga.[30]

In 2006, according to Statistics Canada, there were 166,650 in the Greater Toronto Area who had Cantonese as their native language, while there were 62,850 persons who had Mandarin as their native language. By 2009 Mandarin was becoming the dominant variety of Toronto's Chinese community.[31]

Use and prevalence of Chinese

Many Canadian-born Chinese who grew up in Toronto prior to the 1970s are monolingual English-speakers because they were discouraged from learning their parents' native languages.[32] However Canadian-born Chinese growing up in subsequent eras are encouraged to learn Chinese after Canadian society adopted multiculturalism as a key value.[33]

The 1996 Canadian census stated that the second largest language group in the Toronto area was people who spoke Chinese.[28]

As of the 1997 Chinese Consumer Directory of Toronto there were 97 computer and software businesses, 20 interpreters and translators, 19 sign makers, and eight paging services. Luk wrote that the figures from the directory "indicate the broad range of Chinese language use" throughout the Toronto Chinese community, in society and in private meetings and transactions, even though the directory was "not exhaustive".[11]

In 2000 Bernard Luk wrote "All in all, a Cantonese-speaker living in Toronto should experience no difficulty meeting all essential needs in her or his own language," and that speakers other varieties of Chinese also have services provided in their varieties although the statement about having all needs met is "less true" for non-Cantonese varieties.[11]

Commerce

As of 2000 there are several businesses that provide services tailored to Chinese customers, including banks, restaurants, shopping malls, and supermarkets and grocery stores. Most of them offered services in Cantonese while some also had services in Mandarin.[34]

The Dundas and Spadina intersection in Toronto was where Chinese ethnic commercial activity occurred during the 1980s. Broadview and Gerrard later became the primary point of ethnic Chinese commercial activity. Ethnic Chinese commercial activity in the Toronto districts of North York and Scarborough became prominent in the 1990s. In the late 1990s the suburbs of Markham and Richmond Hill in the York Region gained ethnic Chinese commerce.[19]

In Toronto Chinese commercial activity took place in commercial strips dedicated to the ethnic Chinese. Once the commercial activity began moving into suburban municipalities, indoor malls were constructed to house Chinese commercial activity.[19] These malls also functioned as community centres for Chinese people living in suburban areas.[35] Many such malls were established in Agincourt and Willowdale in Metropolitan Toronto, and in Markham and Richmond Hill.[34] The Pacific Mall in Markham opened in 1997. In 2012 Dakshana Bascaramurty of The Globe and Mail wrote that the popularity of ethnic shopping centres declined and that many ethnic Chinese are preferring to go to mainstream retailers.[19]

Restaurants

As of 2000 most Chinese restaurants in the Toronto area serve Cantonese cuisine and it had been that way historically.[15] Other styles of cuisine available include Beijing, Chaozhou (Chiu Chow), Shanghai, Sichuan,[36] and "Nouvelle Cantonese."[37] Shanghai-style restaurants in the Toronto area include Shanghai-style ones opened by those who directly immigrated from Shanghai to Toronto, as well as Hong Kong and Taiwan-style Shanghai restaurants opened by people who originated from Shanghai and went to Hong Kong and/or Taiwan around 1949 before moving to Toronto later in their lives.[38] There are also "Hong Kong western food" restaurants in the Toronto area, and in general many of the restaurants, as of 2000, cater to persons who originated from Hong Kong.[36] The Toronto Chinese Restaurant Association (Chinese: 多倫多華商餐館同業會; pinyin: Duōlúnduō Huáshāng Cānguǎn Tóngyè Huì) serves the metropolitan area's Chinese restaurants.[15]

Early Chinese settlers in Toronto established restaurants because there was not very much capital needed to establish them. Many of the earliest Chinese-operated restaurants in Toronto were inexpensive and catered to native-born Canadians; they included hamburger restaurants and cafes,[39] and they were predominantly small in size.[40] There were 32 Chinese-operated restaurants in Toronto in 1918, and this increased to 202 by 1923. Many of these restaurants began serving Canadian Chinese cuisine, including chop suey and chow mein, and the number of Canadian Chinese restaurants increased as the food became more and more popular among the Canadian public.[39] The first association of Chinese-operated, Western-style restaurant owners association in Toronto was established in 1923.[41] By the late 1950s larger, fancier restaurants had opened in the Chinatown in Toronto, and several of them catered to non-Chinese.[40] Fatima Lee, the author of "Food as an Ethnic Marker: Chinese Restaurant Food in Toronto," wrote that after large numbers of educated, skilled Chinese arrived in the post-1967 period, the quality of food at Toronto's Chinese restaurants "markedly improved".[9] The first Hong Kong-style restaurant to open in the city was "International Chinese Restaurant" (Chinese: 國際大酒樓; pinyin: Guójì Dà Jiǔlóu; Jyutping: gwok3 zai3 daai6 zau2 lau4[42]) on Dundas Street.[43]

In 1989 the Chinese Business Telephone Directories listed 614 Chinese restaurants in the Toronto area. The 1991 directory listed 785 restaurants. Fatima Lee wrote that the actual number of restaurants may be larger because the directory listing is "by no means exhaustive".[15] During the late 20th century, the influx of people previously resident in Hong Kong, many of whom were originally transplants from Mainland China, caused an increase in variety of Chinese cuisine available in Toronto.[36] Some Toronto Chinese restaurants cater to Jewish persons by offering Kosher-friendly menus.[3]

By 2000 some Indian restaurants operated by ethnic Chinese persons opened in Toronto.[3]

Media

Newspapers

The Sing Wah Daily (醒華日報, P: Xǐng Huá Rìbào) began publication in 1922.[44] Prior to 1967,[11] it was the sole major Chinese newspaper in Toronto.[11][45] Eight pages were in each published edition of the Sing Wah Daily.[11]

New major newspapers were established post-1967 as the Chinese community expanded.[11]

The Chinese Express (快報, P: Kuàibào), a daily newspaper, was published in Toronto.[29]

The Modern Times Weekly (時代周報, P: Shídài Zhōubào[46]), a Chinese newspaper with English summaries, was published in Toronto.[47]

As of 2000 there are three major Chinese-language newspapers published in the Toronto area giving news related to Greater China, Canada, and the world; they have issues with 80 pages each.[11] These newspapers the World Journal, written in Taiwan-style Traditional Chinese and read by people from Taiwan and northern parts of Mainland China, and the Ming Pao Toronto (division of Ming Pao) and Sing Tao Daily, both written in Hong Kong-style Traditional Chinese and read by people from Hong Kong and southern parts of Mainland China.[32] As of that year, altogether the circulation of these newspapers was 80,000.[11]

People from Mainland China also read the People's Daily and the Yangcheng Daily, two newspapers written in Mainland-style Simplified Chinese.[32] According to the 1997 Chinese Consumer Directory of Toronto there were 18 newspapers and publishers.[11]

Broadcast media

Fairchild TV has Cantonese cable programs available. CFMT-DT, as of 2000, has a weekday evening Cantonese news broadcast. In the mid-1990s this broadcast was 30 minutes long, but by 2000 it increased to one hour. As of 2000 the Toronto area has one full-time Chinese radio station and four part-time Chinese radio stations.[44] According to the 1997 Chinese Consumer Directory there were nine television and broadcasting businesses in Toronto.[11]

Other media

Other print media serving the Toronto Chinese community include community group publications, magazines, and newsletters. According to the 1997 Chinese Consumer Directory there were 59 bookstores, 57 printers, 27 karaoke and videotape rental businesses, 13 typesetting businesses, 10 laser disc rental businesses, and two Chinese theatres and cinemas.[11] As of 2000 90% of the Chinese-oriented electronic media in Toronto used Cantonese.[48]

Religion

As of 1999, there are over 23 Buddhist temples and associations in the GTA established by the Chinese.[13] Toronto-area Buddhist and Taoist organizations were established by different subgroups, including Hongkongers, Southeast Asians, and Taiwanese.[34] The Vietnamese Buddhist Temple has worshipers from Chinese Vietnamese and Kinh origins.[49]

Christianity

As of 1994 the Toronto area had 97 Chinese Protestant churches and three Chinese Catholic churches.[50] That year most Protestant denominations each had two to five Chinese churches, while the Baptists had 25 and the Methodists had 11.[18] As of 1994 year the Metropolitan Toronto communities of Scarborough and Willowdale, as well as Markham and Thornhill, had concentrations of Chinese churches.[18] As of 2000 most Chinese churches in the Toronto area hold services in Cantonese, and there are some churches that hold services in Mandarin and Taiwanese Min Nan.[34]

The Young Men's Christian Association established a Chinese mission in Toronto in the 1800s, and Cooke's Presbyterian Church opened its own Chinese mission in 1894 in conjunction with the Christian Endeavour Society. The Presbyterian church became associated with 25 Chinese, about half of the total population in Toronto at the time.[51] The first part-time missionary to work with Chinese people was Thomas Humphreys, who began his work in 1902, and the first full-time Chinese Christian missionary in the city was Ng Mon Hing, who moved from Vancouver to Toronto in 1908. In 1909 the Chinese Christian Association was established.[52] Reverend T. K. Wo Ma, the first Chinese Presbyterian Minister in the Province of Ontario, and his wife Anna Ma jointly set up Toronto's first Chinese Presbyterian Church in a three-storey house at 187 Church Street. The church included a Chinese school and living quarters and 20-30 men made up its initial congregation.[53]

Especially prior to the 1950s missionaries of mainstream Canadian churches established many of the Chinese Protestant churches. Ethnic Chinese immigrant ministers, missionaries originating from Hong Kong, and in some cases missionary departments of Hong Kong-based churches created additional Chinese Protestant congregations.[18] In 1967 the first Chinese Catholic church opened in a former synagogue on Cecil Street in the Dundas-Spadina Chinatown, and the church moved to a former Portuguese mission in 1970. In October 1987 the second Catholic church in the Toronto area, located in Scarborough, opened. The Archdiocese of Toronto gave permission for the opening of the area's third Chinese church in Richmond Hill in 1992.[54] In the 1990s many Chinese Protestant churches intentionally moved to suburban areas where new ethnic Chinese enclaves had formed.[18]

Recreation

The Chinese New Year is celebrated in Toronto. As of 2015 Canada's largest Chinese New Year event is the "Dragon Ball," held at the Allstream Centre. Celebrations occur in the Toronto Chinatown, and the Chinese Cultural Centre of Greater Toronto holds its annual banquet at that time. As of 2015 other elebrations occur in the Toronto Public Library system, at the Toronto Zoo, during the Chinese New Year Carnival China, and in the Markham Civic Centre and Market Village in Markham.[55] Ethnic Chinese employees of the Mississauga-based Maple Leaf Foods developed Chinese-oriented sausages for sale during the Chinese New Year.[56]

The Toronto Chinese Lantern Festival is held in the city.

As of 2000 there were Chinese music clubs in Toronto which put on public singing and opera performances.[44]

As of the 1950s most of the Chinese-language films consumed in Toronto's Chinese community originated from Hong Kong and Taiwan.[27]

Education

Supplementary Chinese education

As of 2000 various Toronto-area school boards have free heritage Chinese language classes for elementary-level students, with most of them being Cantonese classes and some of them being Mandarin and Taiwanese Min Nan classes. Some schools had elementary-level Chinese classes during the regular school day while most had after-school and weekend Chinese classes. Some Toronto-area high schools offered Saturday elective courses in Chinese, with most teaching Cantonese and some teaching Mandarin.[33]

In addition many for-profit companies, churches, and voluntary organizations operate their own Saturday supplementary Chinese language programs and use textbooks from Hong Kong and/or Taiwan. The 1997 Chinese Consumer Directory of Toronto stated that the area had over 100 such schools; Bernard Luk stated that many Saturday schools were not listed in this directory since their parent organizations were very small and did not use yellow pages, so the list was "by no means[...]exhaustive".[57] Many of these schools' students previously attended school in Asian countries and their parents who perceive the classes to be more challenging than those offered by the public schools.[58] There are heritage Chinese classes organized by Hakka persons, and a number of Hakka prefer to use these classes; most of them originated from the Caribbean.[57]

In 1905 Presbyterian churches in Toronto maintained nine Chinese schools.[52]

University education

The University of Toronto (UoT) has a Chinese Student Association. Reza Hasmath, author of A Comparative Study of Minority Development in China and Canada, stated in 2010 that "most confessed their immediate social network comprised mainly of those of Chinese descent."[59]

UoT and York University jointly operate the Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre, which includes archives of Toronto Chinese Canadian print media.[11]

References

- Lee, Fatima (University of Toronto). "Chinese Christian Churches in Metro Toronto." Canada and Hong Kong Update (加港研究通訊 P: Jiā Gǎng Yánjiū Tōngxùn) 11 (Winter 1994). p. 9-10 (PDF document: p. 187-188/224). PDF version (Archive), txt file (Archive).

- Lee, Fatima. "Food as an Ethnic Marker: Chinese Restaurant Food in Toronto." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Volume 15, 2000. Start p. 57.

- Levine, Paul. "Power in the 1950s Toronto Chinese Community: In-groups and Outcasts." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Start p. 18.

- Luk, Bernard H. K. "The Chinese Communities of Toronto: Their Languages and Mass Media." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Start p. 46.

- McLellan, Janet (University of Toronto). "Chinese Buddhists in Toronto" (Chapter 6). In: McLellan, Janet. Many Petals of the Lotus: Five Asian Buddhist Communities in Toronto. University of Toronto Press, 1999. ISBN 0802082254, 9780802082251. Start p. 159.

- Tong, Irene. "Chinese-Canadian Associations in Toronto." Canada and Hong Kong Update (加港研究通訊 P: Jiā Gǎng Yánjiū Tōngxùn) 4 (Spring 1991). p. 12-13 (PDF document: p. 62-63/224). PDF version (Archive), txt file (Archive).

- Watson, Jeff. "An Early History of the Chinese in Toronto: 1877-1930." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Start p. 13.

Notes

- ↑ Watson, p. 13 (Archive).

- 1 2 Levine, p. 19 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 Levine, p. 18 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 4 Burney, Shehla (1995). Coming to Gum San : the story of Chinese Canadians. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario. ISBN 0-669-95470-5. - Cited: p. 31 (Archive).

- ↑ Watson, p. 14 (Archive).

- ↑ Watson, p. 15 (Archive).

- ↑ Watson, p. 16 (Archive).

- ↑ Watson, p. 17 (Archive).

- 1 2 Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 60 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 48 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 54 (Archive).

- 1 2 McLellan, Janet (University of Toronto). "Vietnamese Buddhists in Toronto" (Chapter 4). In: McLellan, Janet. Many Petals of the Lotus: Five Asian Buddhist Communities in Toronto. University of Toronto Press, 1999. ISBN 0802082254, 9780802082251. Start p. 101. CITED: p. 105-106.

- 1 2 3 4 McLellan, "Chinese Buddhists in Toronto," p. 159.

- ↑ Ng, Wing Chung. The Chinese in Vancouver, 1945-80: The Pursuit of Identity and Power (Contemporary Chinese Studies Series). UBC Press, November 1, 2011. ISBN 0774841583, 9780774841580. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 61 (Archive). Full page view (Archive)

- ↑ Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 63 (Archive).

- ↑ Poy, Vivienne. Passage to Promise Land: Voices of Chinese Immigrant Women to Canada. McGill-Queen's Press (MQUP), Apr 1, 2013. ISBN 077358840X, 9780773588400. Google Books p. PT22 (page unspecified).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lee, Fatima, "Chinese Christian Churches in Metro Toronto," p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Bascaramurty, Daksha. "The rise and fall of the ethnic mall." The Globe and Mail. Friday June 15, 2012. Retrieved on October 29, 2014.

- ↑ Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 53 (Archive)-54 (Archive).

- 1 2 Levine, p. 20 (Archive).

- ↑ Levine, p. 23 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 Tong, Irene, p. 13. Address of HKCBA: "347 Bay Street, Suite 1100 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2R7" Address of CCNC: "386 Bathurst St., 2nd Floor, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2S6" TADC address: "Suite 407, 253 College Street, Toronto, Ontario M5T 1R5"

- 1 2 Tong, Irene, p. 12. Address of CCC: "900 Don Mills Road, Unit 3 Toronto, Ontario M3C 1V8" Address of TCBA: "P.O. Box 100, Station B[Continued on p. 13]Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C3"

- 1 2 3 4 Levine, p. 21 (Archive).

- ↑ Levine, p. 19 (Archive)-20 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 4 Levine, p. 22 (Archive).

- 1 2 Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 46 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 Luk, Bernard H.K., p. 47 (Archive). Address of the Chinese Express: "530 Dundas St. W. Suite 203, Toronto, Ont. Canada M5T 1H3"

- 1 2 3 Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 49 (Archive).

- ↑ "Tongues wagging over rise of Mandarin" (Archive). Toronto Star. Thursday October 22, 2009. Retrieved on March 15, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Luk, Bernard H.K., p. 50 (Archive).

- 1 2 Luk, Bernard H.K., p. 51 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 4 Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 53 (Archive).

- ↑ Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 64 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 62 (Archive).

- ↑ Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 61 (Archive)-62 (Archive).

- ↑ Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 65 (Archive).

- 1 2 Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 57 (Archive).

- 1 2 Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 59 (Archive).

- ↑ Ng, Winnie. "The Organization of Chinese Restaurant Workers." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Volume 15, 2000. Start: p. 41. CITED: p. 41 (Archive).

- ↑ Ng, Winnie. "The Organization of Chinese Restaurant Workers." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Volume 15, 2000. Start: p. 41. CITED: p. 44 (Archive

- ↑ Ng, Winnie. "The Organization of Chinese Restaurant Workers." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Volume 15, 2000. Start: p. 41. CITED: p. 42 (Archive).

- 1 2 3 Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 55 (Archive) - Closeup view (Archive). Address of Sing Wah Daily: "12 Hagerman Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5G 1A7"

- ↑ Lee, Fatima, "Food as an Ethnic Marker," p. 58 (Archive).

- ↑ "This item is part of Modern Times Weekly, February 4, 1986." Multicultural Canada. Retrieved on March 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Modern Times Weekly [newspaper]." Multicultural Canada. Retrieved on March 20, 2015.

- ↑ Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 48 (Archive)-49 (Archive).

- ↑ McLellan, Janet (University of Toronto). "Vietnamese Buddhists in Toronto" (Chapter 4). In: McLellan, Janet. Many Petals of the Lotus: Five Asian Buddhist Communities in Toronto. University of Toronto Press, 1999. ISBN 0802082254, 9780802082251. Start p. 101. CITED: p. 106.

- ↑ Luk, Bernard H. K., p. 56 (Archive).

- ↑ Wang, Jiwu. "His Dominion" and the "Yellow Peril": Protestant Missions to Chinese Immigrants in Canada, 1859-1967 (Volume 31 of Editions in the study of religion). Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, May 8, 2006. ISBN 0889204853, 9780889204850. p. 62.

- 1 2 Wang, Jiwu. "His Dominion" and the "Yellow Peril": Protestant Missions to Chinese Immigrants in Canada, 1859-1967 (Volume 31 of Editions in the study of religion). Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, May 8, 2006. ISBN 0889204853, 9780889204850. p. 63.

- ↑ Nipp, Dora. "Family, Work, and Survival: Chinese Women in Ontario." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Volume 15, 2000. Start: p. 36. CITED: p. 37 (Archive.

- ↑ Lee, Fatima, "Chinese Christian Churches in Metro Toronto," p. 10.

- ↑ Himmelsbach, Vawn. "Where to celebrate Chinese New Year in the GTA" (Archive). Toronto Star. February 19, 2015. Retrieved on April 5, 2015.

- ↑ Infantry, Ashante. "Chinese New Year forges new links" (Archive). Toronto Star. February 15, 2015. Retrieved on April 5, 2015.

- 1 2 Luk, Bernard H.K., p. 52 (Archive).

- ↑ Luk, Bernard H.K., p. 51 (Archive)-52 (Archive).

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza. A Comparative Study of Minority Development in China and Canada. Palgrave Macmillan, June 8, 2010. ISBN 023010777X, 9780230107779. p. 79.

Further reading

- Chan, Arlene. The Chinese in Toronto from 1878: From Outside to Inside the Circle. Dundurn Press, 2011. ISBN 1554889790, 9781554889792. See preview at Google Books.

- Chan, Arlene. The Chinese Community in Toronto: Then and Now. Dundurn Press, May 18, 2013. ISBN 1459707710, 9781459707719. See preview at Google Books.

- Goossen, Tam. "Political and Community Activism in Toronto: 1970-2000." In: The Chinese in Ontario. Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Volume 15, 2000. Start p. 24.

- Green, Eva. The Chinese in Toronto: An Analysis of Their Migration History, Background and Adaptation to Canada. See profile at Google Books.

- Lum, Janet. "Recognition and the Toronto Chinese Community" in Reluctant Adversaries: Canada and the People's Republic of China, 1949-1970. Edited by Paul M. Evans and B. Michael Frolic, 217-239. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1991. - On the viewpoints of Canada's recognition of the PRC from the Chinese in Toronto.

- Chinese Canadian National Council. "Jin Guo Voices of Chinese Canadian Women", 1992, Women's Press ISBN 0-88961-147-5

External links

- Chinese Cultural Centre of Greater Toronto (CCCGT; 大多倫多中華文化中心)

- Chinese Professionals Association of Canada (CPAC; 加拿大中国专业人士协会)

- Caribbean Chinese Association (西印度群島華人誼社)

- Confederation of Greater Toronto Chinese Business Association (CGTCBA)

- Toronto Chinese Business Association (多倫多華商會)

- Metro Toronto Chinese & Southeast Asian Legal Clinic

.jpg)