Bruce Chatwin

| Bruce Chatwin | |

|---|---|

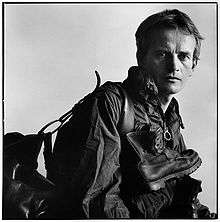

Bruce Chatwin, photographed by Lord Snowdon, 28 July 1982 | |

| Born |

13 May 1940 near Sheffield, England |

| Died |

18 January 1989 (aged 48) Nice, France |

| Occupation | Novelist, travel writer, art and antiquities advisor |

| Nationality | British (English) |

| Period | 1977–89 |

| Genre | travel, fiction |

| Subject | Nomadism, slave trade |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Chanler |

Charles Bruce Chatwin (13 May 1940 – 18 January 1989) was an English travel writer, novelist, and journalist. His first book, In Patagonia (1977), established Chatwin as a travel writer, although he considered himself instead a storyteller, interested in bringing to light unusual tales. He won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for his novel On the Black Hill (1982) and his novel Utz (1988) was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. In 2008 The Times named Chatwin #46 on their list of "50 Greatest British Writers Since 1945."

Chatwin was born near Sheffield, England. At 18 he went to work at Sotheby’s in London, where he gained an extensive knowledge of art and eventually ran the auction house’s Antiquities and Impressionist Art departments. In 1966 he left Sotheby’s to read archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, but he abandoned his studies after two years to pursue a career as a writer.

The Sunday Times Magazine hired Chatwin in 1972. He travelled the world for work and interviewed figures such as the politicians Indira Gandhi and André Malraux. He left the magazine in 1974 to visit Patagonia, which resulted in his first book. He produced five other books, including The Songlines (1987), which was a bestseller. His work is credited with reviving the genre of travel writing, and his works influenced other writers such as William Dalrymple, Claudio Magris, Philip Marsden, Luis Sepúlveda, and Rory Stewart.

Married and bisexual, Chatwin was one of the first prominent men in Great Britain known to have contracted HIV and to have died of an AIDS-related illness, although he hid the details. Following his death, the gay community criticised Chatwin for keeping his diagnosis secret.

Life

Early life

Bruce Chatwin was born on 13 May 1940 in the Shearwood Road Nursing Home in Sheffield, England to Margharita (née Turnell) and Charles Chatwin.[1] His mother Margharita had grown up in Sheffield and worked for the local Conservative party prior to her marriage.[2] His father Charles was a lawyer from Birmingham who joined the Royal Naval Reserve following the outbreak of World War II.[3][4]

Chatwin's early years were spent moving regularly with his mother while his father was at sea.[5] Prior to his birth, Chatwin's parents had lived at Barnt Green, Worcestershire, but Margharita moved to her parents' house in Dronfield, near Sheffield shortly before giving birth.[6] Mother and son remained there for only a few weeks.[7] Worried about Nazi bombs, she sought a safer place to stay.[8] Margharita took her son with her as they travelled to stay with various relatives during the war. They would remain in one place until either Margharita decided to move out of concern for their safety, or because of friction among family members.[9] Later in life Chatwin recalled of the war, "Home, if we had one, was a solid black suitcase called the Rev-Robe, in which there was a corner for my clothes and my Mickey Mouse gas mask."[10]

During the war Chatwin and his mother stayed at the home of his paternal grandparents, who had a curiosity cabinet that fascinated him. Among the items it contained was a "piece of brontosaurus" (actually a mylodon, a giant sloth), which had been sent to Chatwin's grandmother by her cousin Charles Milward. Travelling in Patagonia, Milward had discovered the remains of a giant sloth, which he later sold to the British Museum. He sent his cousin a piece of the animal's skin, and members of the family mistakenly referred to it as a "piece of brontosaurus." The skin was later lost but it inspired Chatwin decades later to visit and write about Patagonia.[11]

After the war, Chatwin lived with his parents and younger brother Hugh (born in 1944[12]) in West Heath in Birmingham, where his father had a law practice.[13] At the age of seven he was sent to boarding school at Old Hall School in Shropshire, and then Marlborough College, in Wiltshire.[14] An unexceptional student, he garnered attention from his performances in school plays.[15] While at Marlborough, Chatwin attained A-levels in Latin, Greek, and Ancient History.[16]

Chatwin had hoped to read Classics at Merton College, Oxford, but the end of National Service in the United Kingdom meant there was more competition for university places. He was forced to consider other options. His parents discouraged the ideas he offered—an acting career or work in the Colonial Service in Kenya. Instead, Chatwin's father asked one of his clients for a letter of introduction to the auction house Sotheby's. An interview was arranged, and Chatwin secured a job there.[17]

Art and archaeology

In 1958, Chatwin moved to London to begin work as a porter in the Works of Art department at Sotheby's.[18] Chatwin was ill-suited for this job, which included dusting objects that had been kept in storage.[19] Sotheby's moved him to a junior cataloger position working in both the Antiquities and Impressionist Art departments.[20] This position enabled him to develop his eye for art, and he quickly became known for his ability to discern forgeries.[21][22] His work as a cataloguer also taught him to describe objects in a concise manner and required that he research these objects.[23] Chatwin advanced to become Sotheby's expert on Antiquities and Impressionist art and would later run both departments.[24] Many of Chatwin's colleagues thought he would eventually become chairman of the auction house.[25]

During this period Chatwin travelled extensively for his job and also for adventure.[26] Travel offered him a relief from the British class system, which he found stifling.[27] An admirer of Robert Byron and his book, The Road to Oxiana, he travelled twice to Afghanistan.[28] He also used these trips to visit markets and shops where he would buy antiques which he would resell at a profit in order to supplement his income from Sotheby's.[29] He became friends with artists and art collectors and dealers.[30][31] One friend, Howard Hodgkin, painted Chatwin in The Japanese Screen (1962). Chatwin said he was the "acid green smear on the left."[32]

Chatwin was ambivalent about his sexual orientation and had affairs with both men and women during this period of his life.[33] One of his girlfriends, Elizabeth Chanler, an American and a descendent of John Jacob Astor, was a secretary at Sotheby's.[34] Chanler had earned a degree in history from Radcliffe College and worked at Sotheby's New York offices for two years before transferring to their London office in 1961.[35] Her love of travel and independent nature appealed to Chatwin.[36]

In the mid-1960s Chatwin grew unhappy at Sotheby's. There were various reasons for his disenchantment. Both women and men found Chatwin attractive, and Peter Wilson, then chairman of Sotheby's, used this appeal to the auction house's advantage when using Chatwin to try to persuade wealthy individuals to sell their art collections. Chatwin became increasingly uncomfortable with the situation.[37] Later in life Chatwin also spoke of having become "burnt out" and said, "In the end I felt I might just as well be working for a rather superior funeral parlour. One's whole life seemed to be spent valuing for probate the apartment of somebody recently dead."[38]

In late 1964 he began to suffer from problems with his sight, which he attributed to the close analysis of artwork entailed by his job. He consulted eye specialist Patrick Trevor-Roper, who diagnosed a latent squint and recommended that Chatwin take a six-month break from his work at Sotheby's. Trevor-Roper had been involved in the design of an eye hospital in Addis Ababa, and suggested Chatwin visit east Africa. In February 1965, Chatwin left for Sudan.[39] It was on this trip that Chatwin first encountered a nomadic tribe; their way of life intrigued him. "My nomadic guide," he wrote, "carried a sword, a purse and a pot of scented goat's grease for anointing his hair. He made me feel overburdened and inadequate ..."[40] Chatwin would remain fascinated by nomads for the rest of his life.[41]

Chatwin returned to Sotheby's and, to the surprise of his friends, proposed marriage to Elizabeth Chanler.[42] They married on 21 August 1965.[43] Chatwin was bisexual throughout their married life, a circumstance Elizabeth knew and accepted.[44] Chatwin had hoped he would "grow out of" his homosexual behaviour and have a successful marriage like his parents.[45] During their marriage, Chatwin had many affairs, mostly with men. Some who were aware of Chatwin's affairs with men assumed the Chatwins had a chaste marriage but, according to Nicholas Shakespeare, the author's biographer, this was not true.[46] Both Chatwin and his wife had hoped to have children, but they remained childless.[47]

In April 1966, at the age of 26, Chatwin was promoted to a director of Sotheby's, a position to which he had aspired.[48] To his disappointment, he was made a junior director and lacked voting rights on the board.[49] This disappointment, along with boredom and increasing discomfort over potentially illegal side deals taking place at Sotheby's, including the sale of objects from the Pitt-Rivers museum collection, led Chatwin to resign from his Sotheby's post in June 1966.[50]

Chatwin enrolled in October 1966 at the University of Edinburgh to study Archaeology.[51] He had regretted not attending Oxford and had been contemplating going to university for a few years. A visit in December 1965 to the Hermitage in Leningrad sparked his interest in the field of archaeology.[52] Despite winning the Wardrop Prize for the best first year's work,[53] he found the rigour of academic archaeology tiresome, and he left after two years without taking a degree.[54]

The Nomadic Alternative

Following his departure from Edinburgh, Chatwin decided to pursue a career as a writer, successfully pitching a book proposal on nomads to Tom Maschler, publisher at Jonathan Cape. Chatwin tentatively titled the book The Nomadic Alternative and sought to answer the question "Why do men wander rather than stand still?"[55] Chatwin delivered the manuscript in 1972, and Maschler declined to publish it, calling it a "chore to read."[56][57]

Between 1969 and 1972, as he was working on The Nomadic Alternative, Chatwin travelled extensively and pursued other endeavours in an attempt to establish a creative career. He co-curated an exhibit on Nomadic Art of the Asian Steppes, which opened at Asia House Gallery in New York City in 1970.[58] He considered publishing an account of his 1969 trip to Afghanistan with Peter Levi.[59] Levi published his own book about it, The Light Garden of the Angel King: Journeys in Afghanistan (1972).[60] Chatwin contributed two articles on nomads to Vogue and another article to History Today.[61]

In the early 1970s Chatwin had an affair with James Ivory, a film director. He pitched stories to him for possible films, which Ivory did not take seriously.[62] In 1972 Chatwin tried his hand at film-making and travelled to Niger to make a documentary about nomads.[63] The film was lost while Chatwin was trying to sell it to European television companies.[64]

Chatwin also took photographs of his journeys and attempted to sell photographs from a trip to Mauritania to The Sunday Times Magazine.[65] While The Times did not accept those photographs for publication, it did offer Chatwin a job.[66]

The Sunday Times Magazine and In Patagonia

In 1972, The Sunday Times Magazine hired Chatwin as an adviser on art and architecture.[67] Initially his role was to suggest story ideas and put together features such as "One Million Years of Art," which ran in several issues during the summer of 1973.[68] His editor, Francis Wyndham, encouraged him to write, which allowed him to develop his narrative skills.[69] Chatwin travelled on many international assignments, writing on such subjects as Algerian migrant workers and the Great Wall of China, and interviewing such diverse people as André Malraux, Maria Reiche, and Madeleine Vionnet.[70][71]

In 1972, Chatwin interviewed the 93-year-old architect and designer Eileen Gray in her Paris salon, where he noticed a map she had painted of the area of South America called Patagonia.[72] "I've always wanted to go there," Chatwin told her. "So have I," she replied, "Go there for me."[73]

Two years later, in November 1974, Chatwin flew out to Lima in Peru and reached Patagonia a month later.[74] He would later claim that he sent a telegram to Wyndham merely stating: "Have gone to Patagonia." Actually he sent a letter: "I am doing a story there for myself, something I have always wanted to write up."[75] This marked the end of Chatwin's role as a regular writer for The Sunday Times Magazine, although in subsequent years he contributed occasional pieces, including a profile of Indira Gandhi.[76]

Chatwin spent six months in Patagonia, travelling around gathering stories of people who came from elsewhere and settled there. This trip resulted in the book, In Patagonia (1977). He used his quest for his own "piece of brontosaurus" (the one from his grandparents' cabinet had been thrown away years earlier) to frame the story of his trip. Chatwin described In Patagonia as "the narrative of an actual journey and a symbolic one ... It is supposed to fall into the category or be a spoof of Wonder Voyage: the narrator goes to a far country in search of a strange animal: on his way he lands in strange situations, people or other books tell him strange stories which add up to form a message."[77]

In Patagonia contains fifteen black and white photographs by Chatwin. According to Susannah Clapp, who edited the book, "Rebecca West amused Chatwin by telling him that these were so good they rendered superfluous the entire text of the book."[78]

This work established Chatwin's reputation as a travel writer. One of his biographers, Nicholas Murray, called In Patagonia "one of the most strikingly original postwar English travel books"[79] and said that it revitalised the genre of travel writing.[80] However, residents in the region contradicted the account of events depicted in Chatwin's book. It was the first time in his career, but not the last, that conversations and characters which Chatwin presented as fact were later alleged to be fiction.[81]

For In Patagonia Chatwin received the Hawthornden Prize and the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[82] Graham Greene, Patrick Leigh Fermor, and Paul Theroux praised the book.[83] As a result of the success of In Patagonia, Chatwin's circle of friends expanded to include individuals such as Jacqueline Onassis, Susan Sontag, and Jasper Johns.[84]

Ouidah and the Black Hills

Upon his return from Patagonia, Chatwin discovered a change in leadership at The Sunday Times Magazine and his retainer was not continued.[85] Chatwin intended his next project to be a biography of Francisco Félix de Sousa, a nineteenth-century slave trader born in Brazil who became the Viceroy of Ouidah in Dahomey (present day Benin). Chatwin had first heard of de Sousa during a visit to Dahomey in 1972.[86] He returned to the country, by then renamed the People's Republic of Benin, in December 1976 to conduct research.[87] In January 1977 a coup took place, and Chatwin was accused of being a mercenary, arrested, and detained for three days.[88] Chatwin later wrote about this experience in "A Coup—A Story," which was published in Granta and included in What Am I Doing Here (1989).[89]

Following his arrest and release Chatwin left Benin and went to Brazil to continue his research on de Sousa.[90] Frustrated by the lack of documented information on de Sousa, Chatwin chose instead to write a fictionalised biography of him.[91] This book was published in 1980, and Werner Herzog's film, Cobra Verde (1987), is based on it.[92][93]

Although The Viceroy of Ouidah received good reviews, it did not sell well. Nicholas Shakespeare said that the dismal sales caused Chatwin to pursue a completely different subject for his next book.[94] In response to his growing reputation as a travel writer Chatwin said he "decided to write something about people who never went out."[95] His next book, On the Black Hill (1982), is a novel of twin brothers who live all of their lives in a farmhouse on the Welsh borders.[96] For this book Chatwin won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Whitbread Prize for Best First Novel, even though he considered his previous book, The Viceroy of Ouidah, a novel.[97] It was made into a film in 1987.[98]

In the late 1970s Chatwin spent an increasing amount of time in New York City. He continued to have affairs with men, but most of these affairs were short-lived. In 1977 he began his first serious affair with Donald Richards, an Australian stockbroker.[99] Richards introduced him to the gay nightclub scene in New York.[100] During this period Chatwin became acquainted with Robert Mapplethorpe, who photographed him. Chatwin is one of the few men Mapplethorpe photographed fully clothed.[101] Chatwin later contributed the introduction to a book of Mapplethorpe's photographs, Lady, Lisa Lyon (1983).[102]

Although Elizabeth Chatwin had accepted her husband's affairs, their relationship deteriorated in the late 1970s, and in 1980 she asked for a separation.[103] By 1982 Chatwin's affair with Richards had ended and he began another serious affair with Jasper Conran.[104]

The Songlines

In 1983 Chatwin returned to the topic of nomads and decided to focus on Aboriginal Australians.[105] He was influenced by the work of Theodore Strehlow, author of Songs of Central Australia and a controversial figure.[106] Strehlow had collected and recorded Aboriginal songs, and shortly before his death in 1978, he sold photographs of secret Aboriginal initiation ceremonies to a magazine.[107]

Chatwin went to Australia to learn more about Aboriginal culture, specifically the songlines or dreaming tracks.[108] Each songline is a personal story and functions as a creation tale and a map, and each Aboriginal Australian has their own songline.[109] Chatwin thought the songlines could be a metaphor he could use to support his ideas about humans' need to wander, which he believed was genetic. However, he struggled to fully understand and describe the songlines and their place in Aboriginal culture.[110] This was due to Chatwin's approach to learning about the songlines. He spent several weeks in 1983 and 1984 in Australia, during which he primarily relied on non-Aboriginal people for information. Chatwin was limited by his inability to speak the Aboriginal languages. He interviewed people involved in the Land Rights movement, and he alienated many of them because he was oblivious to the politics and also because he was an admirer of Strehlow's work.[111]

While in Australia, Chatwin, who had been experiencing some health problems, first read about AIDS, then known as the gay plague. It frightened him and compelled him to reconcile with his wife.[112] The fear of AIDS also drove him to finish the book that became The Songlines (1987). His friend the novelist Salman Rushdie said, "That book was an obsession too great for him ... His illness did him a favour, got him free of it. Otherwise, he would have gone on writing it for ten years."[113]

The Songlines features a narrator named Bruce whose biography is almost identical to Chatwin's.[114] The narrator spends time in Australia trying to learn about Aboriginal culture, specifically the songlines. As the book goes on, it becomes a reflection on what Chatwin stated was "for me, the question of questions: the nature of human restlessness."[115] Chatwin also hinted at his preoccupation over his own mortality in the text: "I had a presentiment that the 'travelling' phase of my life might be passing ... I should set down on paper a resume of the ideas, quotations, and encounters that amused me and obsessed me ..."[116] Following this statement in The Songlines Chatwin included extensive excerpts from his moleskine notebooks.[117]

Chatwin published The Songlines in 1987, and it became a bestseller in both the United Kingdom and the United States.[118] The book was nominated for the Thomas Cook Travel Award, but Chatwin requested that it be withdrawn from consideration, saying the work was fictional.[119] Following its publication, Chatwin became friends with composer Kevin Volans, who was inspired to base a theatre score on the book. The project evolved into an opera, The Man with Footsoles of Wind (1993).[120]

Illness and final works

While at work on The Songlines between 1983 and 1986, Chatwin frequently came down with colds.[121] He also developed skin lesions that may have been symptoms of Kaposi's sarcoma.[122] After finishing The Songlines in August 1986, Chatwin went to Switzerland, where he collapsed on the street.[123] At a clinic there, he was diagnosed as HIV-positive.[124] Chatwin provided different reasons to his doctors as to how he might have contracted HIV, including from a gang rape in Dahomey or possibly from Sam Wagstaff, the patron and lover of Robert Mapplethorpe.[125]

Chatwin's case was unusual as he had a fungal infection, Penicillium marneffei, which at the time had rarely been seen and only in South Asia. It is now known as an AIDS-defining illness, but in 1986 little was known about HIV and AIDS. Doctors were not certain if all cases of HIV developed into AIDS. The rare fungus gave Chatwin hope that he might be different and served as the basis of what he told most people about his illness. He gave various reasons for how he became infected with the fungus—ranging from eating a 1,000-year-old egg to exploring a bat cave in Indonesia.[126] He never publicly disclosed that he was HIV-positive because of the stigma at the time. He wanted to protect his parents, who were unaware of his homosexual affairs.[127]

Although he never spoke or wrote publicly about his disease, in one instance he did write about the AIDS epidemic in 1988 in a letter to the editor of the London Review of Books:

"The word 'Aids' is one of the cruellest and silliest neologisms of our time. 'Aid' means help, succour, comfort—yet with a hissing sibilant tacked onto the end it becomes a nightmare ... HIV (Human Immuno-Deficiency Virus) is a perfectly easy name to live with. 'Aids' causes panic and despair and has probably done something to facilitate the spread of the disease."[128]

During his illness, Chatwin continued to write. Elizabeth encouraged him to use a letter he had written to her from Prague in 1967 as an inspiration for a new story.[129] During this trip, he had met Konrad Just, an art collector.[130] This meeting and the letter to Elizabeth served as the basis for Chatwin's next work. Utz (1988) was a novel about the obsession that leads people to collect.[131] Set in Prague, the novel details the life and death of Kaspar Utz, a man obsessed with his collection of Meissen porcelain.[132] Utz was well-received and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize.[133]

Chatwin also edited a collection of his journalism, which was published as What Am I Doing Here (1989).[134] At the time of his death in 1989, he was working on a number of new ideas for future novels, including a transcontinental epic provisionally titled Lydia Livingstone.[135]

Chatwin died at a hospital in Nice on 18 January 1989.[136] A memorial service was held in the Greek Orthodox Church of Saint Sophia in West London on 14 February 1989, the same day that a fatwa was announced on Salman Rushdie, a close friend of Chatwin's, who attended the service.[137] Paul Theroux, who also attended the service, later commented on it and Chatwin in a piece for Granta.[138] The novelist Martin Amis described the memorial service in the essay "Salman Rushdie", included in his anthology Visiting Mrs Nabokov.[139]

Chatwin's ashes were scattered near a Byzantine chapel above Kardamyli in the Peloponnese. This was close to the home of one of his mentors, the writer Patrick Leigh Fermor.[140] Near here, Chatwin had spent several months in 1985 working on The Songlines.[141]

Chatwin's papers, including 85 moleskine notebooks, were given to the Bodleian Library, Oxford.[142] Two collections of his photographs and excerpts from the moleskine notebooks were published as Photographs and Notebooks (US title: Far Journeys) in 1993 and Winding Paths in 1999.[143][144]

News of Chatwin's AIDS diagnosis first surfaced in September 1988. However, at the time of his death, obituaries referred to Chatwin's statements about a rare fungal infection. Following his death, members of the gay community criticised Chatwin for lacking the courage to reveal the true nature of his illness, which some people think would have raised public awareness of AIDS, as he was one of the first high-profile individuals in Great Britain known to have contracted HIV.[145][146]

Writing style

John Updike described Chatwin's writing as "a clipped, lapidary prose that compresses worlds into pages",[147] while one of Chatwin's editors, Susannah Clapp, wrote, "Although his syntax was pared down, his words were not-or at least not only-plain. ... His prose is both spare and flamboyant."[148] Chatwin's writing was shaped by his work as a cataloguer at Sotheby's, which provided him with years of practice writing concise yet vivid descriptions of objects with the intention of enticing buyers.[149] In addition, Chatwin's interest in nomads also influenced his writing. One aspect of nomadic culture that interested him was the few possessions they had. Their spartan way of life appealed to his aesthetic sense, and it was something he sought to emulate in both his life and his writing. He strove to strip unnecessary objects from his life and unnecessary words from his prose.[150]

In his writing Chatwin experimented with format. With In Patagonia, Clapp said Chatwin described the book's structure of 97 vignettes as "Cubist." "[I]n other words," she said, "lots of small pictures tilting away and toward each other to create this strange original portrait of Patagonia."[151] The Songlines was another attempt by Chatwin to experiment with format.[152] The book begins as a novel narrated by a man named Bruce but about two-thirds of the way through it becomes a commonplace book filled with quotations, anecdotes, and summaries of others' research in an attempt to explore human restlessness.[153] Some of Chatwin's critics did not think he succeeded in The Songlines with this approach, although others applauded his effort at trying an unconventional structure.[154]

Several nineteenth and twentieth century writers influenced Chatwin's work. The work of Robert Byron influenced Chatwin, who admitted to imitating his style when he first began making notes of his own travels.[155] While in Patagonia he read In Our Time by Ernest Hemingway. Chatwin admired Hemingway for his spare prose.[156] While writing In Patagonia, Chatwin strove to approach his writing as a "literary Cartier-Bresson."[157] Chatwin's biographer described the resulting prose as "quick snapshots of ordinary people."[158] Along with Hemingway and Cartier-Bresson, Osip Mandelstam's work strongly influenced Chatwin during the writing of In Patagonia. An admirer of Noël Coward, Chatwin found the breakfast scene in Private Lives helpful in learning to write dialogue.[159] Once Chatwin began work on The Viceroy of Ouidah, he began studying the work of nineteenth-century French authors, such as Honoré de Balzac and Gustave Flaubert. These writers would continue to influence Chatwin for the remainder of his life.[160]

Themes

Chatwin explored several different themes in his work. They include human restlessness and wandering; borders and exile; and art and objects.[161][162][163]

Chatwin considered the question of human restlessness to be the focus of his writing. He ultimately aspired to explore this subject in order to answer what he believed was a fundamental question about human existence.[164][165] He thought humans were meant to be a migratory species but once they settled in one place, their natural urges "found outlets in violence, greed, status-seeking or a mania for the new."[166] In his first attempt at writing a book, The Nomadic Alternative, Chatwin had tried to compose an academic exposition on nomadic culture, which he believed was unexamined and unappreciated.[167][168] With this volume Chatwin had hoped to answer the question "Why do men wander rather than sit still?"[169] In his book proposal he admitted that the interest in the subject was personal: "Why do I become restless after a month in a single place, unbearable after two?"[170]

Although Chatwin did not succeed with The Nomadic Alternative, he returned to the topic of restlessness and wandering in his subsequent books. Writer Jonathan Chatwin (no relation) stated that Chatwin's works can be grouped into two categories: "restlessness defined" and "restlessness explained." Most of his work focuses on describing restlessness, such as in the case of one twin in On the Black Hill who longs to leave home.[171] Another example is the protagonist of Utz, who feels restless to escape to Vichy each year but always returns to Prague.[172] Chatwin attempted to explain restlessness in The Songlines, which focused on the Aboriginal Australians' walkabout. For this work, he returned to his research from The Nomadic Alternative.[173][174]

Borders are another theme in Chatwin's work. According to Elizabeth Chatwin, he "was interested in borders, where things were always changing, not one thing or another."[175] Patagonia, the subject of his first published book, is an area that is in both Argentina and Chile.[176] The Viceroy of Ouidah is a Brazilian who trades slaves in Dahomey.[177] On the Black Hills takes place on the borders of Wales and England.[178] In The Songlines the characters the protagonist mostly interacts with are people who provide a bridge between the Aboriginal and white Australian worlds.[179] The main character in Utz travels back and forth across the Iron Curtain.[180]

"The theme of exile, of people living at the margins ... is treated in a literal and metaphorical sense throughout Chatwin's work," stated Nicholas Murray. He identified several examples in Chatwin's work. There were people who were actual exiles, such as some of those profiled in In Patagonia and the Viceroy of Ouidah, who was unable to return to Brazil. Murray also cited the main characters in On the Black Hill, "although not strictly exiles ... [they] were exiles from the major events of their time and its dominant values." Similarly, Murray wrote, Utz is "trapped in a society whose values are not his own but which he cannot bring himself to leave."[181]

Chatwin returned to the subject of art and objects during his career. In his early writing for the Sunday Times Magazine, he wrote about art and artists, and many of these articles Chatwin included in What Am I Doing Here.[182] The main focus of Utz is on the impact the possession of art (in this case porcelain figures) has on a collector.[183] Utz's unwillingness to give up his porcelain collection kept him in Czechoslovakia even though he had the opportunity to live in the West.[184] Chatwin constantly struggled with the conflicting desires to own beautiful items and to live in a space free of unnecessary objects.[185] His distaste for the art world was the result of his days at Sotheby's, and some of his final writing focused on this.[186] The final section of What Am I Doing Here, "Tales from the Art World," consists of four short stories on this topic. At the end of What Am I Doing Here, Chatwin shares an anecdote about advice he had received from Noël Coward, who told him "Never let anything artistic stand in your way." Chatwin stated, "I've always acted on that advice."[187]

Influence

With the publication of In Patagonia, Chatwin invigorated the genre of travel writing; according to his biographer, Nicholas Murray, he "showed that an inventive writer could breathe new life into an old genre."[188] The combination of his clear yet vivid prose and an international perspective at a time when many English writers were more focused on home instead of abroad helped to set him apart.[189][190] Aside from his writing, Chatwin was also good looking, and his image as a dashing traveller added to his appeal and helped make him a celebrity.[191] In the eyes of younger writers such as Rory Stewart, Chatwin "made [travel writing] cool."[192] In The New York Times, Andrew Harvey wrote,

"Nearly every writer of my generation in England has wanted, at some point, to be Bruce Chatwin; wanted, like him, to talk of Fez and Firdausi, Nigeria and Nuristan, with equal authority; wanted to be talked about, as he is, with raucous envy; wanted above all to have written his books."[193]

Chatwin's books also inspired some readers to visit Patagonia and Australia.[194] As a result of his work, Patagonia experienced an increase in tourism,[195] and it became a common sight for tourists to appear in the region, carrying a copy of In Patagonia.[196] The Songlines also inspired readers to travel to Australia and seek out the people Chatwin had based his characters on, much to their consternation, as he had failed to disclose to these individuals his intentions.[197]

Beyond travel, Chatwin influenced other writers, such as Claudio Magris, Luis Sepúlveda, Philip Marsden, and William Dalrymple.[198] Nicholas Shakespeare stated that part of Chatwin's impact was that his work was difficult to categorise and it helped "set free other writers...[from] conventional boundaries.[199] Although he was often called a travel writer, he did not identify as one nor did he consider himself a novelist. ("I don't quite know the meaning of the word novel," he said).[200] He preferred to call his writing stories or searches.[201][202] He was interested in asking big questions about human existence, sharing unusual tales, and making connections between ideas from various sources. His friend and fellow writer Robyn Davidson said, "He posed questions we all want answered and perhaps gave the illusion they were answerable."[203]

Posthumous Influence

According to his biographer Nicholas Shakespeare, Chatwin's work developed a cult-like following in the years immediately following his death.[204] By 1998 one million copies of his books had been sold.[205] However, his reputation diminished following revelations about his personal life and questions about the accuracy of his work.

Questions about the accuracy of his work existed prior to his death, and Chatwin had admitted to "counting up the lies" in In Patagonia, though he stated there were not many.[206] While researching Chatwin's life, Nicholas Shakespeare stated he found "few cases of mere invention" in In Patagonia.[207] Mostly, these tended to be instances of embellishment, such as when Chatwin wrote of a nurse who loved the work of Osip Mandelstam - one of his favorite authors - when in fact she was a fan of Agatha Christie.[208] When Michael Ignatieff asked Chatwin his opinion of what divided fact from fiction, he replied, "I don't think there is [a division]."[209]

Some individuals profiled in In Patagonia were unhappy with Chatwin's portrayals of them. They included one man whom Chatwin insinuated was homosexual and a woman who thought her father was unjustly accused of killing Indians.[210] However, Chatwin's biographer found one farmer who was featured in the book who thought Chatwin's depictions of himself and other members of his community were truthful. He stated, "No one likes looking at their own passport photograph, but I found it accurate. It's not flattering, but it's the truth."[211]

Chatwin's bestseller, The Songlines, has been the focus of much criticism. Some critics describe his viewpoint as "colonialist", citing his lack of interviews with Aboriginals and his reliance instead on white Australians for information about Aboriginal culture.[212] Other criticism comes from anthropologists and other researchers who spent years studying Aboriginal culture and who dismiss Chatwin's work because he visited Australia briefly.[213] There are others, such as writer Thomas Keneally, who believe The Songlines should be widely read in Australia, where many people had not previously heard of the songlines.[214]

The questions about the veracity of Chatwin's writing are compounded by the revelation of his sexual orientation and the true cause of his death.[215] Once it became known that Chatwin had been bisexual and had died of an AIDS-related illness, some critics viewed him as a liar and dismissed his work.[216] Nicholas Shakespeare said, "His denial [of his AIDS diagnosis] bred a sense that if he lied about his life, he must have lied about his work. Some readers have taken this as a cue to pass judgement on his books – or else not to bother with them."[217] In 2010 The Guardian's review of Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin opened with the question, "Does anyone read Bruce Chatwin these days?"[218] However, Rory Stewart has stated, "His personality, his learning, his myths, and even his prose are less hypnotizing [than they once were]. And yet he remains a great writer, of deep and enduring importance.”[219] In 2008 The Times named Chatwin #46 on their list of "50 Greatest British Writers Since 1945".[220]

Legacy

Chatwin's name is used to sell Moleskine notebooks.[221] Chatwin wrote in The Songlines of little black oilskin-covered notebooks that he bought in Paris and which he called "moleskines".[222] The quotes and anecdotes he had compiled in these books serve as a major section of The Songlines. In this book Chatwin mourned the closing of the last producer of these books.[223] In 1995, Marta Sebregondi read The Songlines and proposed to her employer, Modo & Modo, an Italian design and publishing company, that they produce moleskine notebooks.[224] In 1997, the company began to sell these books and used Chatwin's name to promote them.[225] Modo & Modo was sold in 2006, and the company became known as Moleskine SpA.[226]

In 2014 the clothing label Burberry produced a collection inspired by Chatwin's books.[227] The following year Burberry released a limited edition set of Chatwin's books with specially designed covers.[228]

Works

- In Patagonia (1977)

- The Viceroy of Ouidah (1980)

- On the Black Hill (1982)

- The Songlines (1987)

- Utz (1988)

- What Am I Doing Here (1989)

Posthumously Published

- Photographs and Notebooks (1993)

- Anatomy of Restlessness (1997)

- Winding Paths (1998)

Citations

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 24.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 24.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 17.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 21.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 25.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 21.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 22.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1987). The Songlines. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 6.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1977). In Patagonia. London: Jonathan Cape. pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 43.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 22.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 65.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 88.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-385-49829-2.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 86.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. Viking. pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 93.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 95.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 176.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 165.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 119–120, 166–167.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (25 June 1987). "Interview: Bruce Chatwin". Granta (21): 32.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 514.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 119.

- ↑ Clapp (1996). With Chatwin. pp. 101–104.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 98–99; 118–119.

- ↑ Chatwin (1989). What Am I Doing Here. p. 76.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 131–136.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 146–148.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 178.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 123–127.

- ↑ Murray, Nicholas (1994). Bruce Chatwin. Seren Books. pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Chatwin (1996). Anatomy of Restlessness. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 173.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 181.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 178.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 177.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (29 August 2010). "He wandered, but always came back: Bruce Chatwin's letters reveal the rock-solid marriage that survived his gay flings". Sunday Times. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 210.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 189.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 186.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 178.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 189.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 199.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 192.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 214.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1996). Anatomy of Restlessness. New York: Viking. p. 75. ISBN 0-670-86859-0.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 270.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 223.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 218.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 241.

- ↑ Murray (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 35.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 280.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 265.

- ↑ Shakespere (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 272.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 321.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 273–274.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 280.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 267.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 283.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 280

- ↑ Chatwin (1996). Anatomy of Restlessness. p. 13.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, p. 286.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1997). Anatomy of Restlessness. Penguin. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Shakespeare 1999, pp. 287–291.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 301.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 271.

- ↑ Clapp (1996). With Chatwin. p. 94.

- ↑ Murray (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 39.

- ↑ Murray (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 44.

- ↑ Murray (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 51.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 372–373.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 374–375.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 338.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 341.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 348–350.

- ↑ Murray (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 53.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 352.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 356.

- ↑ Chatwin (1989). What Am I Doing Here. pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 417.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 394–395.

- ↑ Clapp, Susannah (1996). With Chatwin. p. 179.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1982). On the Black Hill. London: Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 395.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 417.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 360.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 362–369.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 368.

- ↑ Murray (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 88.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 392–393, 420.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 429, 424.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 426, 433.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 426, 431–432.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 431.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 438.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 458.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 434–442.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 448.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 450.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 440.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. p. 161.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. p. 161.

- ↑ Chatwin. The Songlines. pp. 163–233.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 512.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 512.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 527.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 450, 464, 479, 487.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 450, 522.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 488.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 489.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 490–491.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 493–494.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 491–492.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 594.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 500.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 502.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 503.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1988). Utz. London: Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 507.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 565.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 529–530.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 561.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 571–572.

- ↑ Theroux's "admiring tribute" to Chatwin,

- ↑ Amis, Martin (2012). Visiting Mrs. Nabokov. Vintage. pp. 170–178.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 573.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 465, 469–473.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. xi.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1993). Far Journeys. New York: Viking.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1999). Winding Paths: Photographs from Bruce Chatwin. Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ Murray, Nicholas (1993). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 524–525.

- ↑ Updike, John (1991). Odd Jobs: Essays and Criticism. Knopf. p. 464.

- ↑ Clapp (1996). With Chatwin. p. 45.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 95.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 117, 171, 467–468.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 325.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 513.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 512–513.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1989). What Am I Doing Here. p. 288.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 329.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 307.

- ↑ Chatwin, Bruce (1989). What Am I Doing Here. New York: Viking. p. 366.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 380–383.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. p. 161.

- ↑ Murray (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 45.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 502–505.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. pp. 131–139.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. p. 161.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 230.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 230.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. pp. 131–139.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 132.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun. p. 132.

- ↑ Chatwin, Jonathan (2008). Anywhere Out of the World: Restlessness in the work of Bruce Chatwin. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 508.

- ↑ Chatwin, Jonathan (2008). Anywhere Out of the World: Restlessness in the work of Bruce Chatwin. p. 10.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 483.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 291.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 304.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 340.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 395.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 434–435.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 508.

- ↑ Murray (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 45.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 280–284.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 504–505.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 503.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 197, 505.

- ↑ Chatwin (1989). What Am I Doing Here. p. 366.

- ↑ Murray, Nicholas (1993). Bruce Chatwin. Seren Books. pp. 39, 44.

- ↑ Murray, Nicholas (1993). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 564, 569.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 564.

- ↑ Stewart, Rory (25 June 2012). "Walking with Chatwin". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ Harvey, Andrew (2 August 1987). "Footprints of the Ancestor". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 515, 577.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 577.

- ↑ Allen, Sandra (14 May 2013). "In Patagonia in Patagonia". The Paris Review. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 515.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. p. 569.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. p. 568.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 11.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 11.

- ↑ Murray, Nicholas (1993). Bruce Chatwin. Seren. p. 12.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. p. 569.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin. p. 12.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 578.

- ↑ Murray, Nicholas (1993). Bruce Chatwin. p. 90.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. p. 335.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. New York: Viking. p. 335.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (25 June 1987). "Interview: Bruce Chatwin". Granta (21): 24.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 309.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 307.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 515–516.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 434–435.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. pp. 513, 516.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 566.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Chatwin, Elizabeth (2010). Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin. Jonathan Cape. p. 14.

- ↑ Morrison, Blake (3 September 2010). "Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Stewart, Rory (25 June 2012). "Walking with Chatwin". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ "46. Bruce Chatwin; The 50 Greatest British Writers Since 1945". The Times (London). 5 January 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ Shakespeare (1999). Bruce Chatwin. p. 564.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Chatwin (1987). The Songlines. pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Raphel, Adrienne (14 April 2014). "The Virtual Moleskine". The New Yorker. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Harkin, James (12 June 2011). "Resurrecting Moleskine Notebooks". Newsweek. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Raphel, Adrienne (14 April 2014). "The Virtual Moleskine". The New Yorker. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Marriott, Hannah (17 June 2014). "Books inspire Burberry's show at London Collections: Men". The Guardian.

- ↑ Connor, Liz (8 May 2015). "Burberry's Bruce Chatwin books just made your shelf far more stylish". GQ.

References

- Chatwin, Bruce (2010), Elizabeth Chatwin, ed., Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin, Jonathan Cape, ISBN 978-0-224-08989-0

- Chatwin, Bruce (1990), What Am I Doing Here, Pan, ISBN 0-330-31310-X

- Murray, Nicholas (1993), Bruce Chatwin, Seren, ISBN 1-85411-079-9

- Clapp, Susannah (1997), With Chatwin: Portrait of a Writer, Jonathan Cape, ISBN 978-0-224-03258-2

- Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999), Bruce Chatwin, The Harvill Press, ISBN 1-86046-544-7

- Antonella Riem, La gabbia innaturale – l'opera di Bruce Chatwin (pp. 175). UDINE: Campanotto (Italy). 1993.

Documentaries

- Paul Yule, In The Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin (2x60 mins), BBC, 1999 – Berwick Universal Pictures

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bruce Chatwin |

- "Bruce Chatwin", a resource for news related to Bruce Chatwin and his work

- "On the Black Hill." Entry in Literary Encyclopedia

- "The Songlines." Entry in Literary Encyclopedia

- "Bruce Chatwin." Entry in Literary Encyclopedia

- Moleskine official website

- Bruce Chatwin at the Internet Movie Database