Alexander Gorchakov

| Alexander Gorchakov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire | |

|

In office 27 April 1856 – 9 April 1882 | |

| Preceded by | Karl Nesselrode |

| Succeeded by | Nikolay Girs |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

15 June 1798 Haapsalu, Estonia, Russian Empire |

| Died |

11 March 1883 (aged 84) Baden-Baden, German Empire |

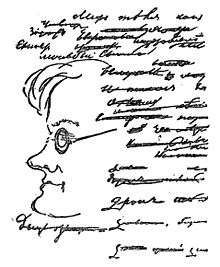

| Signature |

|

Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov (Russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Горчако́в), (15 June 1798 – 11 March 1883[1]) was a Russian statesman from the Gorchakov princely family. He has an enduring reputation as one of the most influential and respected diplomats of the nineteenth century.[2]

Early life and career

Gorchakov was born at Haapsalu, Governorate of Estonia, and was educated at the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, where he had the poet Alexander Pushkin as a school-fellow. He became a good classical scholar, and learned to speak and write in French with facility and elegance. Pushkin in one of his poems described young Gorchakov as Fortune's favoured son, and predicted his success.[3]

On leaving the lyceum Gorchakov entered the foreign office under Count Nesselrode. His first diplomatic work of importance was the negotiation of a marriage between the grand duchess Olga and the crown prince Charles of Wurttemberg. He remained at Stuttgart for some years as Russian minister and confidential adviser of the crown princess. He foretold the outbreak of the revolutionary spirit in Germany and Austria, and was credited with counselling the abdication of Ferdinand in favour of Francis Joseph. When the German Confederation was re-established in 1850 in place of the parliament of Frankfurt, Gorchakov was appointed Russian minister to the diet. It was here that he first met Prince Bismarck, with whom he formed a friendship which was afterwards renewed at St Petersburg.

The emperor Nicholas found that his ambassador at Vienna, Baron Meyendorff, was not a sympathetic instrument for carrying out his schemes in the East. He therefore transferred Gorchakov to Vienna, where the latter remained through the critical period of the Crimean War. Gorchakov perceived that Russian designs against Turkey, which was supported by Britain and France, were impracticable, and he counselled Russia to make no more useless sacrifices, but to accept the basis of a pacification. At the same time, although he attended the Paris conference of 1856, he purposely abstained from affixing his signature to the treaty of peace after that of Count Orlov, Russia's chief representative. For the time, however, he made a virtue of necessity, and Alexander II, recognising the wisdom and courage which Gorchakov had exhibited, appointed him minister of foreign affairs in place of Count Nesselrode.[4][5]

Gorchakov's promotion of Dreikaiserbund

Not long after his accession to office Gorchakov issued a circular to the foreign powers, in which he announced that Russia proposed, for internal reasons, to keep herself as free as possible from complications abroad, and he added the now historic phrase, La Russie ne boude pas; elle se recueille ('Russia is not sulking, she is composing herself'). During the Polish insurrection Gorchakov rebuffed the suggestions of Britain, Austria and France for assuaging the severities employed in quelling it, and he was especially acrid in his replies to Earl Russell's despatches. The Prussian support was assured by the Alvensleben Convention. In July 1863 Gorchakov was appointed chancellor of the Russian empire expressly in reward for his bold diplomatic attitude towards an indignant Europe. The appointment was hailed with enthusiasm in Russia.[6]

A rapprochement now began between the courts of Russia and Prussia; and in 1863 Gorchakov smoothed the way for the occupation of Holstein by the Federal troops. This seemed equally favourable to Austria and Prussia, but it was the latter power which gained all the substantial advantages. When conflict arose between Austria and Prussia in 1866, Russia remained neutral and permitted Prussia to reap the benefits arising from the conflict and establish her supremacy in Germany.

In 1867 Russia and the US concluded the sale of Alaska, a process which began as early as 1854 during the Crimean War. Gorchakov was not against the sale but always advocated for careful and secret negotiations, seeing the eventuality of the sale but not the immediate necessity.

When the Franco-German War of 1870-71 broke out, Russia argued for the neutrality of Austria. An attempt was made to form an anti-Prussian coalition, but it failed because of the cordial understanding between the German and Russian chancellors.

In return for Russia's service in preventing Austrian support being given to France, Gorchakov looked to Bismarck for diplomatic support on the Eastern Question, and he received an instalment of the expected support when he successfully denounced the Black Sea clauses of the treaty of Paris. This was justly regarded by him as an important service to his country and one of the triumphs of his career, and he hoped to obtain further successes with the assistance of Germany. However, the cordial relations between the cabinets of St Petersburg and Berlin did not last much longer.

Gorchakov and Bismarck

In 1875 Bismarck was suspected of having designs to again attack France, and Gorchakov let him know, in a way which was not meant to be offensive, but which roused the German chancellor's indignation, that Russia would oppose any such scheme. The tension thus produced between the two statesmen was increased by the political complications of 1875–1878 in south-eastern Europe, which began with the Herzegovian insurrection and culminated at the Berlin Congress. Gorchakov hoped to utilise the complications of the situation in such a way as to recover, without war, the portion of Bessarabia ceded by the treaty of Paris, but he soon lost control of events, and the Slavophile agitation produced the Russo-Turkish campaign of 1877-78.

By the preliminary peace of San Stefano, the Slavic aspirations seemed to be realised, but the stipulations of that peace were considerably modified by the Berlin Congress (13 June to 13 July 1878), at which the aged chancellor held nominally the post of first plenipotentiary, but left to the second plenipotentiary, Count Shuvalov, not only the task of defending Russian interests, but also the responsibility and odium for the concessions which Russia had to make to Britain and Austria. He had the satisfaction of seeing the lost portion of Bessarabia restored to his country by the Berlin treaty, but at the cost of greater sacrifices than he anticipated.

Gorchakov considered the Berlin treaty the greatest failure of his official career. After the congress he continued to hold the post of foreign minister, but lived chiefly abroad, with Dmitry Milyutin taking responsibility for foreign affairs. Gorchakov resigned formally in 1882, when he was succeeded by Nicholas de Giers. He died at Baden-Baden and was buried at the family vault in Strelna Monastery.[6]

Assessment

Prince Gorchakov devoted himself entirely to foreign affairs, and took some part in the great internal reforms of Alexander II's reign: for example he submitted 4 projects of Emancipation reform and also presented to Alexander II analysis of foreign experience of various reforms.[7] As a diplomatist he displayed many brilliant qualities: adroitness in negotiation, incisiveness in argument and elegance in style. His statesmanship, though marred occasionally by personal vanity and love of popular applause, was far-seeing and prudent. In the latter part of his career his main object was to raise the prestige of Russia by undoing the results of the Crimean War, and it may fairly be said that he in great measure succeeded.

Bibliography

- Проект письмо г. министра к генерал-адмиралу, 1857

| Preceded by Karl Nesselrode |

Foreign Minister of Russia 1856–1882 |

Succeeded by Nicholas de Giers |

References

- ↑ Приморская Троицкая пустынь. Могила Горчакова

- ↑ Памятник Горчакову А. М.

- ↑ Сайт Международного фонда канцлера Горчакова

- ↑ России — идеология государственного патриотизма.

- ↑ Иванов А. А. «Россия не сердится, Россия сосредотачивается» // Русская народная линия, 12.03.2014

- 1 2 ЭСБЕ/Горчаков

- ↑ see. В. Лопатников Горчаков, ЖЗЛ, М. 2004

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.