Champ Ferguson

| Champ Ferguson | |

|---|---|

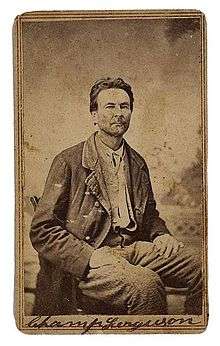

Champ Ferguson in 1865 | |

| Born |

November 29, 1821 Clinton County, Kentucky |

| Died |

October 20, 1865 (aged 43) Tennessee |

| Resting place |

France Cemetery White County, Tennessee 36°01′32″N 85°20′15″W / 36.02567°N 85.33742°W |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Murder, 53 counts {Suspect claimed over 100 victims} |

Champ Ferguson (November 29, 1821 – October 20, 1865) was a notorious Confederate guerrilla during the American Civil War. He claimed to have killed over 100 Union soldiers and pro-Union civilians.

Early life

Ferguson was born in Clinton County, Kentucky, on the Tennessee border, the oldest of ten children. This area was known as the Kentucky Highlands and had more families who were yeomen farmers; they generally owned few slaves. Like his father, Ferguson became a farmer. But the younger Ferguson also earned a reputation for violence even before the American Civil War.[1]

Reportedly, in 1858, he led a group of men who tied Sheriff James Read of Fentress County, Tennessee to a tree. Ferguson rode his horse in circles around the tree, hacking at Read repeatedly with a sword until he was dead. He also allegedly stabbed a man named Evans at a camp meeting, though Evans survived.[1] In the 1850s, Ferguson moved with his wife and family to the Calfkiller River Valley in White County, Tennessee.

Guerrilla activities

During the Civil War, East Tennessee, a mostly mountainous region, was generally opposed and, in many areas, strongly opposed to secession from the Union.[2] The remainder of the state, which had more slaveholders, particularly in the plantation areas of West Tennessee, supported the Confederacy. This historical division made East Tennessee a target for unofficial engagements by both sides. In addition, Confederate troops were committed to engagements with local partisans, which took place far from the front. From 1862, Tennessee was occupied by Union troops, which contributed to the tensions and divisions. The mountainous terrain and lack of law enforcement during the war gave guerrillas and other irregular military groups significant freedom of action. Numerous incidents were recorded of guerrilla and revenge attacks, especially on the Cumberland Plateau. Families were often divided among their members. For example, one of Champ Ferguson's brothers fought as a member of the Union's 1st Kentucky Cavalry and was killed in action.[3]

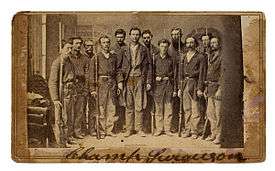

Early in the war, Ferguson organized a guerrilla company and began attacking any civilians he believed supported the Union. Many local feuds were carried out in occupied Tennessee under the guise of war. His men cooperated with Confederate military units led by Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler when they were in the area, and some evidence indicates that Morgan commissioned Ferguson as a captain of partisan rangers. But Ferguson's men were seldom subject to military discipline and often violated the normal rules of warfare.

Stories circulated about Ferguson's alleged sadism, including tales that he on occasion would decapitate his prisoners and roll their heads down hillsides. He was said to be willing to kill elderly and bedridden men. He was once arrested by the Confederate authorities and charged with murdering a government official and was imprisoned for two months in Wytheville, Virginia. The charges could not be proven, and he was eventually released.

Trial and hanging

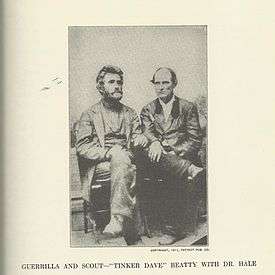

At the war's end, Ferguson disbanded his men and returned home to his farm. As soon as the Union troops learned he was back, they arrested him and took him to Nashville. There he was tried by a military court for 53 murders. Ferguson's trial attracted national attention and soon became a major media event. One of Ferguson's main adversaries on the Union side, "Tinker Dave" Beaty, testified against him.[4] Just as Ferguson had led a band of guerrillas against any real/or suspected unionists, Beaty had led his own band of guerrillas against any real/or suspected confederates. Not surprisingly each had done his best to kill the other. Ferguson acknowledged his band had killed many of the victims named and said he had killed over 100 men himself. He insisted this conduct was simply part of his duty as a soldier.

A notorious incident is Ferguson and his guerrilla band's involvement in killing wounded Union men and prisoners after the Battle of Saltville is a matter of dispute. The victims were members of the all-black 5th United States Colored Cavalry and their white officers. Ferguson and his men were charged with murdering the wounded in their hospital beds. Only the arrival of Thomas' Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders had prevented the complete slaughter of the prisoners. As soon as Ferguson learned that regular Confederates had arrived, he left with his men.

On October 10, 1865, Ferguson was found guilty and sentenced to hang. He made a statement in response to the verdict:

I am yet and will die a Rebel … I killed a good many men, of course, but I never killed a man who I did not know was seeking my life. … I had always heard that the Federals would not take me prisoner, but would shoot me down wherever they found me. That is what made me kill more than I otherwise would have done. I repeat that I die a Rebel out and out, and my last request is that my body be removed to White County, Tennessee, and be buried in good Rebel soil.— Johnson, James, Execution of Champ Ferguson, James K. Polk Papers, Box 1, Folder 9. (Tennessee State Library and Archives; Nashville Dispatch, 22 October 1865).

He was hanged on October 20, 1865, one of only two men to be tried, convicted and executed for war crimes during the Civil War (the other being Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the infamous Andersonville prison in Georgia). Ferguson was buried in the France Cemetery north of Sparta, White County, Tennessee. This site is now bordered by Highway 84 (Monterey Highway).

After his execution, Ferguson's statements to the Nashville Dispatch were published; the New York Times classified his letter as a confession. He admitted to killing at least ten people. Ferguson claimed nine of these men were killed in self-defense. He believed that one was committing murders and robbing private houses. Ferguson also stated that he had been convicted of the murders of several men who were killed by other members of his group. He denied some of the charges, including the killing of 12 soldiers at Saltville, saying that many of the men he was accused of killing had died in battle or been killed by bands other than his own. Ferguson felt that his trial had been neither just nor fair; he knew he would be sentenced to death, and questioned the reliability of all but two of the witnesses.[5]

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 "Notorious Characters – The Fergusons – Atrocious Murders, Etc." The Patriots and Guerrillas – Chapter II. WebRoots.org.

- ↑ p 43 Studies in Tennessee Politics, Tennessee Votes 1799-1976

- ↑ " 'I took time by the Forelock' Champ Ferguson's war" Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., North & South Magazine, Volume 11, Number 1, Page 16, published by the Civil War Society, accessed April 16, 2010

- ↑ Bryant, Lloyd D. "David "Tinker Dave" Beaty – (L2)." History of Fentress County, Tennessee], The Fentress County Historical Society.

- ↑ Anonymous (October 29, 1865). "CHAMP FERGUSON.; Confession of the Culprit. (abbreviated title)". New York Times. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

References

- Johnson, James. "Execution of Champ Ferguson." James K. Polk Papers, Box 1, Folder 9. (Tennessee State Library and Archives; Nashville Dispatch, 22 October 1865).

- McDade, Arthur, "Tennessee Guerrilla Champ Ferguson Killed More Than 100 Men Before Facing The Hangman's Noose". America's Civil War. March 2001, Vol. 14, No. 1.

- Mays, Thomas D. Cumberland Blood: Champ Ferguson's Civil War. Southern Illinois University Press, 2008.

External links

- Re: Champ Ferguson Ky/Tn. 1821-1865 - Ferguson Family Genealogy Forum - Genealogy.com {reference only}

- "Guerilla Warfare in Kentucky" – Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

- Stacey Graham (January 4, 2010). "Samuel 'Champ' Ferguson (1821–1865)". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- Smith, Troy D. (December 2001). "Champ Ferguson: An American Civil War Rebel Guerrilla". Civil War Times. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- Champ Ferguson at Find a Grave