Building block (chemistry)

Building block is a term in chemistry which is used to describe a virtual molecular fragment or a real chemical compound the molecules of which possess reactive functional groups.[1] Building blocks are used for bottom-up modular assembly of molecular architectures: nano-particles,[2][3] metal-organic frameworks,[4] organic molecular constructs, supra-molecular complexes. [5] Using building blocks ensures strict control of what a final compound or a (supra)molecular construct will be.[6]

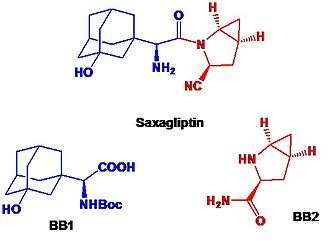

Building blocks for medicinal chemistry

In medicinal chemistry, the term defines either imaginable, virtual molecular fragments or chemical reagents from which drugs or drug candidates might be constructed or synthetically prepared.[7]

Virtual building blocks

Virtual building blocks are used in drug discovery for drug design and virtual screening, addressing the desire to have controllable molecular morphologies that interact with biological targets.[8] Of special interest for this purpose are the building blocks common to known biologically active compounds, in particular, known drugs,[9] or natural products.[10] There are algorithms for de novo design of molecular architectures by assembly of drug-derived virtual building blocks.[11]

Chemical reagents as building blocks

Organic functionalized molecules (reagents), carefully selected for the use in modular synthesis of novel drug candidates, in particular, by combinatorial chemistry, or in order to realize the ideas of virtual screening and drug design are also called building blocks.[12] [13] To be practically useful for the modular drug or drug candidate assembly, the building blocks should be either mono-functionalised or possessing selectively chemically addressable functional groups, for example, orthogonally protected.[14] Selection criteria applied to organic functionalized molecules to be included in the building block collections for medicinal chemistry are usually based on empirical rules aimed at drug-like properties of the final drug candidates.[15] [16] Bioisosteric replacements of the molecular fragments in drug candidates could be made using analogous building blocks.[17]

Building blocks and chemical industry

The building block approach to drug discovery changed the landscape of chemical industry which supports medicinal chemistry.[18] Major chemical suppliers for medicinal chemistry like Maybridge,[19] Chembridge,[20] Enamine[21] adjusted their business correspondingly.[22] By the end of the 1990th the use of building block collections prepared for fast and reliable construction of small-molecule sets of compounds (libraries) for biological screening became one of the major strategies for pharmaceutical industry involved in drug discovery; modular, usually one-step synthesis of compounds for biological screening from building blocks turned out to be in most cases faster and more reliable than multistep, even convergent syntheses of target compounds.[23]

There are online web-resources such as eMolecules (over 1.5 million building blocks by 2016),[24] BIOVIA Available Chemicals Directory (ACD, more than 10 million unique compounds by 2016)[25] or Chemspace (over 15 million building blocks by 2016)[26] which provide access to available building blocks for medicinal chemistry.

Examples

Typical examples of building block collections for medicinal chemistry are libraries of fluorine-containing building blocks.[27] [28] Introduction of the fluorine into a molecule has been shown to be beneficial for its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, therefore, the fluorine-substituted building blocks in drug design increase the probability of finding drug leads.[29] Other examples include natural and unnatural amino acid libraries,[30] collections of conformationally constrained bifunctionalized compounds[31] and diversity-oriented building block collections.[32]

References

- ↑ H.H. Szmant (1989). Organic Building Blocks of the Chemical Industry. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ L. Zang, Y. Che, J.S. Moore (2008). "One-Dimensional Self-Assembly of Planar π-Conjugated Molecules: Adaptable Building Blocks for Organic Nanodevices". Acc. Chem. Res. 41 (12): 1596–1608. doi:10.1021/ar800030w.

- ↑ J.M.J. Fréchet (2003). "Dendrimers and other dendritic macromolecules: From building blocks to functional assemblies in nanoscience and nanotechnology". J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 41: 3713–3725. doi:10.1002/pola.10952.

- ↑ O. K. Farha, C. D. Malliakas, M.G. Kanatzidis, J.T. Hupp (2010). "Control over Catenation in Metal−Organic Frameworks via Rational Design of the Organic Building Block". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (3): 950–952. doi:10.1021/ja909519e.

- ↑ A.J. Cairns , J.A. Perman , L. Wojtas , V.Ch. Kravtsov , M.H. Alkordi , M.Eddaoudi , M.J. Zaworotko (2008). "Supermolecular Building Blocks (SBBs) and Crystal Design: 12-Connected Open Frameworks Based on a Molecular Cubohemioctahedron". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (5): 1560–1561. doi:10.1021/ja078060t.

- ↑ R.S. Tu, M. Tirrell. (2004). "Bottom-up design of biomimetic assemblies". Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 56 (11): 1537–1563. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.047.

- ↑ G. Schneider, M.-L. Lee, M. Stahl, P. Schneider (2000). "De novo design of molecular architectures by evolutionary assembly of drug-derived building blocks". J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 14: 487–494. doi:10.1023/A:1008184403558.

- ↑ J. Wang, T. Hou (2010). "Drug and Drug Candidate Building Block Analysis". J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50 (1): 55–67. doi:10.1021/ci900398f.

- ↑ A. Kluczyk, T. Popek, T. Kiyota, P. de Macedo, P. Stefanowicz, C. Lazar,;Y. Konishi (2002). "Drug Evolution: p-Aminobenzoic Acid as a Building Block". Curr. Med. Chem. 9 (21): 1871–1892. doi:10.2174/0929867023368872.

- ↑ R.Breinbauer, I. R. Vetter, H.Waldmann (2002). "From Protein Domains to Drug Candidates—Natural Products as Guiding Principles in the Design and Synthesis of Compound Libraries". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41: 2878–2890. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16<2878::AID-ANIE2878>3.0.CO;2-B.

- ↑ G. Schneider, U. Fechner (2005). "Computer-based de novo design of drug-like molecules". Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 4: 649–663. doi:10.1038/nrd1799.

- ↑ A. Linusson , J. Gottfries , F. Lindgren , S. Wold (2000). "Statistical Molecular Design of Building Blocks for Combinatorial Chemistry". J. Med. Chem. 43 (7): 1320–1328. doi:10.1021/jm991118x.

- ↑ G. Schneider, H.-J. Böhm (2002). "Virtual screening and fast automated docking methods". Drug Discovery Today. 7 (1). doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(01)02091-8.

- ↑ A.N. Shivanyuk, D.M. Volochnyuk, I.V. Komarov, K.G. Nazarenko, D.S. Radchenko, A. Kostyuk, A.A. Tomachev (2007). "Conformationally restricted monoprotected diamines as scaffolds for design of biologically active compounds and peptidomimetics". Chimica Oggi/Chemistry Today. 25 (3): 12–13.

- ↑ I. Muegge (2003). "Selection criteria for drug-like compounds". Med. Res. Rev. 23: 302–321. doi:10.1002/med.10041.

- ↑ F.W. Goldberg, J.G. Kettle, T. Kogej, M.W.D. Perry, N.P. Tomkinson (2015). "Designing novel building blocks is an overlooked strategy to improve compound quality". Drug Discovery Today. 20 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2014.09.023.

- ↑ A.V. Tymtsunik, V.A. Bilenko, S.O. Kokhan, O.O. Grygorenko, D.M. Volochnyuk, I.V. Komarov (2012). "1-Alkyl-5-((di)alkylamino) Tetrazoles: Building Blocks for Peptide Surrogates". J. Org. Chem. 77: 1174−1180. doi:10.1021/jo2022235.

- ↑ "A MARKET GROWS, BLOCK BY BLOCK. Pharmaceutical building-block business attracts firms from ACROSS THE GLOBE". Chem. Eng. News. 89 (18): 16–18. 2011. doi:10.1021/cen-v089n018.p016.

- ↑ "Maybridge building blocks and reactive intermediates".

- ↑ "Building Blocks: Key Facts".

- ↑ "Building Blocks for Drug Discovery".

- ↑ Lowe, Derek. "Good Suppliers – And The Other Guys".

- ↑ J. Drews (2000). "Drug Discovery: A Historical Perspective". Science. 287: 1960–1964. doi:10.1126/science.287.5460.1960.

- ↑ "eMolecules Database".

- ↑ "ACD Database".

- ↑ "Chemspace Database".

- ↑ M Schlosser (2006). "CF3-Bearing Aromatic and Heterocyclic Building Blocks". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (33): 5432–5446. doi:10.1002/anie.200600449.

- ↑ V.S. Yarmolchuk, O.V. Shishkin, V.S. Starova, O.A. Zaporozhets, O. Kravchuk, S. Zozulya, I.V. Komarov, P.K. Mykhailiuk (2013). "Synthesis and Characterization of β-Trifluoromethyl-Substituted Pyrrolidines". Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013 (15): 3086–3093. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300121.

- ↑ I. Ojima (2009). Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9781444312096.fmatter.

- ↑ I.V. Komarov, A.O. Grigorenko, A.V. Turov, V.P. Khilya (2004). "Conformationally rigid cyclic α-amino acids in the design of peptidomimetics, peptide models and biologically active compounds". Russian Chemical Reviews. 73 (8): 785–810.

- ↑ O.O. Grygorenko, D.S. Radchenko, D.M. Volochnyuk, A.A. Tolmachev, I.V. Komarov (2011). "Bicyclic Conformationally Restricted Diamines". Chem. Rev. 111 (9): 5506–5568. doi:10.1021/cr100352k.

- ↑ S.L. Schreiber (2009). "Organic chemistry: Molecular diversity by design". Nature. 457: 153–154. doi:10.1038/457153a.